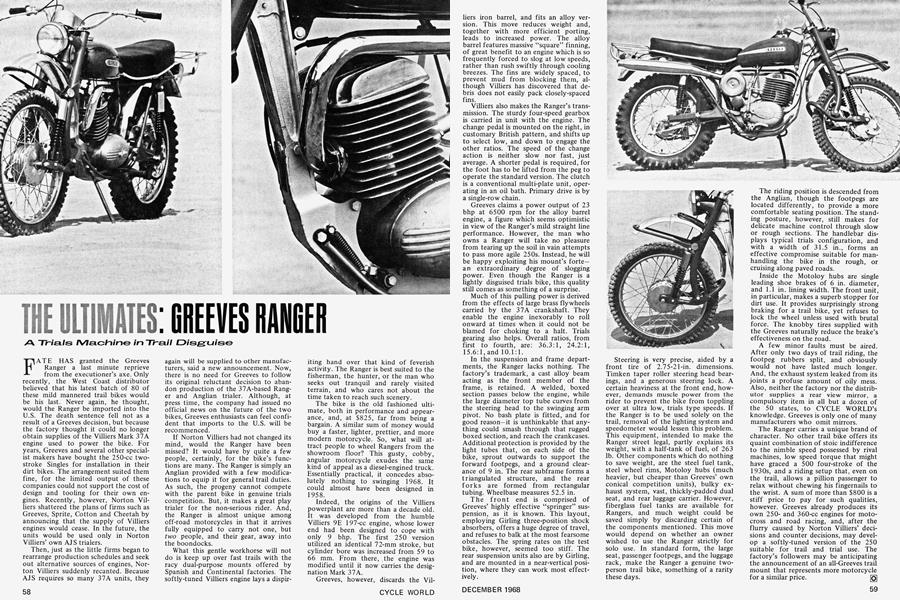

THE ULTIMATES: GREEVES RANGER

A Trials Machine in Trail Disguise

FATE HAS granted the Greeves Ranger a last minute reprieve from the executioner’s axe. Only recently, the West Coast distributor believed that his latest batch of 80 of these mild mannered trail bikes would be his last. Never again, he thought, would the Ranger be imported into the U.S. The death sentence fell not as a result of a Greeves decision, but because the factory thought it could no longer obtain supplies of the Villiers Mark 37A engine used to power the bike. For years, Greeves and several other specialist makers have bought the 250-cc twostroke Singles for installation in their dirt bikes. The arrangement suited them fine, for the limited output of these companies could not support the cost of design and tooling for their own engines. Recently, however, Norton Villiers shattered the plans of firms such as Greeves, Sprite, Cotton and Cheetah by announcing that the supply of Villiers engines would cease. In the future, the units would be used only in Norton Villiers’ own AJS trialers.

Then, just as the little firms began to rearrange production schedules and seek out alternative sources of engines, Norton Villiers suddenly recanted. Because AJS requires so many 37A units, they again will be supplied to other manufacturers, said a new announcement. Now, there is no need for Greeves to follow its original reluctant decision to abandon production of the 37A-based Ranger and Anglian trialer. Although, at press time, the company had issued no official news on the future of the two bikes, Greeves enthusiasts can feel confident that imports to the U.S. will be recommenced.

If Norton Villiers had not changed its mind, would the Ranger have been missed? It would have by quite a few people, certainly, for the bike’s functions are many. The Ranger is simply an Anglian provided with a few modifications to equip it for general trail duties. As such, the progeny cannot compete with the parent bike in genuine trials competition. But, it makes a great play trialer for the non-serious rider. And, the Ranger is almost unique among off-road motorcycles in that it arrives fully equipped to carry not one, but two people, and their gear, away into the boondocks.

What this gentle workhorse will not do is keep up over fast trails with the racy dual-purpose mounts offered by Spanish and Continental factories. The softly-tuned Villiers engine lays a dispiriting hand over that kind of feverish activity. The Ranger is best suited to the fisherman, the hunter, or the man who seeks out tranquil and rarely visited terrain, and who cares not about the time taken to reach such scenery.

The bike is the old fashioned ultimate, both in performance and appearance, and, at $825, far from being a bargain. A similar sum of money would buy a faster, lighter, prettier, and more modern motorcycle. So, what will attract people to wheel Rangers from the showroom floor? This gusty, cobby, angular motorcycle exudes the same kind of appeal as a diesel-engined truck. Essentially practical, it concedes absolutely nothing to swinging 1968. It could almost have been designed in 1958.

Indeed, the origins of the Villiers powerplant are more than a decade old. It was developed from the humble Villiers 9E 197-cc engine, whose lower end had been designed to cope with only 9 bhp. The first 250 version utilized an identical 72-mm stroke, but cylinder bore was increased from 59 to 66 mm. From there, the engine was modified until it now carries the designation Mark 3 7 A.

Greeves, however, discards the Villiers iron barrel, and fits an alloy version. This move reduces weight and, together with more efficient porting, leads to increased power. The alloy barrel features massive “square” finning, of great benefit to an engine which is so frequently forced to slog at low speeds, rather than rush swiftly through cooling breezes. The fins are widely spaced, to prevent mud from blocking them, although Villiers has discovered that debris does not easily pack closely-spaced fins.

Villiers also makes the Ranger’s transmission. The sturdy four-speed gearbox is carried in unit with the engine. The change pedal is mounted on the right, in customary British pattern, and shifts up to select low, and down to engage the other ratios. The speed of the change action is neither slow nor fast, just average. A shorter pedal is required, for the foot has to be lifted from the peg to operate the standard version. The clutch is a conventional multi-plate unit, operating in an oil bath. Primary drive is by a single-row chain.

Greeves claims a power output of 23 bhp at 6500 rpm for the alloy barrel engine, a figure which seems optimistic in view of the Ranger’s mild straight line performance. However, the man who owns a Ranger will take no pleasure from tearing up the soil in vain attempts to pass more agile 250s. Instead, he will be happy exploiting his mount’s tortean extraordinary degree of slogging power. Even though the Ranger is a lightly disguised trials bike, this quality still comes as something of a surprise.

Much of this pulling power is derived from the effects of large brass flywheels carried by the 37A crankshaft. They enable the engine inexorably to roll onward at times when it could not be blamed for choking to a halt. Trials gearing also helps. Overall ratios, from first to fourth, are: 36.3:1, 24.2:1, 15.6:1, and 10.1:1.

In the suspension and frame departments, the Ranger lacks nothing. The factory’s trademark, a cast alloy beam acting as the front member of the frame, is retained. A welded, boxed section passes below the engine, while the large diameter top tube curves from the steering head to the swinging arm pivot. No bash plate is fitted, and for good reason—it is unthinkable that anything could smash through that rugged boxed section, and reach the crankcases. Additional protection is provided by the light tubes that, on each side of the bike, sprout outwards to support the forward footpegs, and a ground clearance of 9 in. The rear subframe forms a triangulated structure, and the rear forks are formed from rectangular tubing. Wheelbase measures 52.5 in.

The front end is comprised of Greeves’ highly effective “springer” suspension, as it is known. This layout, employing Girling three-position shock absorbers, offers a huge degree of travel, and refuses to balk at the most fearsome obstacles. The spring rates on the test bike, however, seemed too stiff. The rear suspension units also are by Girling, and are mounted in a near-vertical position, where they can work most effectively.

Steering is very precise, aided by a front tire of 2.75-21-in. dimensions. Timken taper roller steering head bearings, and a generous steering lock. A certain heaviness at the front end, however, demands muscle power from the rider to prevent the bike from toppling over at ultra low, trials type speeds. If the Ranger is to be used solely on the trail, removal of the lighting system and speedometer would lessen this problem. This equipment, intended to make the Ranger street legal, partly explains its weight, with a half-tank of fuel, of 263 lb. Other components which do nothing to save weight, are the steel fuel tank, steel wheel rims, Motoloy hubs (much heavier, but cheaper than Greeves’ own conical competition units), bulky exhaust system, vast, thickly-padded dual seat, and rear luggage carrier. However, fiberglass fuel tanks are available for Rangers, and much weight could be saved simply by discarding certain of the components mentioned. This move would depend on whether an owner wished to use the Ranger strictly for solo use. In standard form, the large seat, passenger footpegs, and the luggage rack, make the Ranger a genuine twoperson trail bike, something of a rarity these days.

The riding position is descended from the Anglian, though the footpegs are located differently, to provide a more comfortable seating position. The standing posture, however, still makes for delicate machine control through slow or rough sections. The handlebar displays typical trials configuration, and with a width of 31.5 in., forms an effective compromise suitable for manhandling the bike in the rough, or cruising along paved roads.

Inside the Motoloy hubs are single leading shoe brakes of 6 in. diameter, and 1.1 in. lining width. The front unit, in particular, makes a superb stopper for dirt use. It provides surprisingly strong braking for a trail bike, yet refuses to lock the wheel unless used with brutal force. The knobby tires supplied with the Greeves naturally reduce the brake’s effectiveness on the road.

A few minor faults must be aired. After only two days of trail riding, the footpeg rubbers split, and obviously would not have lasted much longer. And, the exhaust system leaked from its joints a profuse amount of oily mess. Also, neither the factory nor the distributor supplies a rear view mirror, a compulsory item in all but a dozen of the 50 states, to CYCLE WORLD’S knowledge. Greeves is only one of many manufacturers who omit mirrors.

The Ranger carries a unique brand of character. No other trail bike offers its quaint combination of stoic indifference to the nimble speed possessed by rival machines, low speed torque that might have graced a 500 four-stroke of the 1930s, and a riding setup that, even on the trail, allows a pillion passenger to relax without chewing his fingernails to the wrist. A sum of more than $800 is a stiff price to pay for such qualities, however. Greeves already produces its own 250and 360-cc engines for motocross and road racing, and, after the flurry caused by Norton Villiers’ decisions and counter decisions, may develop a softly-tuned version of the 250 suitable for trail and trial use. The factory’s followers may be anticipating the announcement of an all-Greeves trail mount that represents more motorcycle for a similar price. [o]