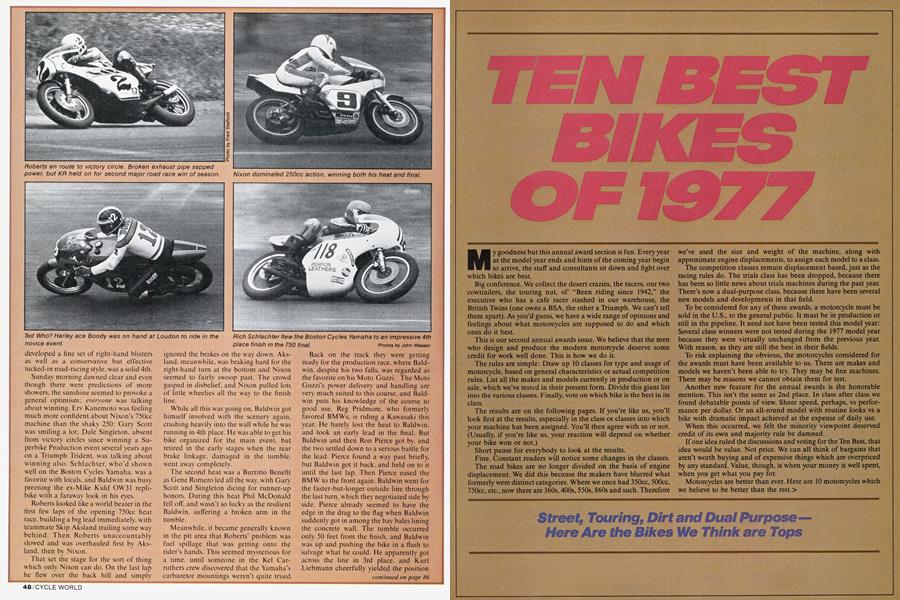

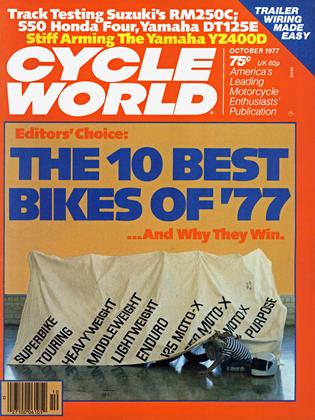

TEN BEST BIKES OF 1977

Street, Touring, Dirt and Dual Purpose— Here Are the Bikes We Think are Tops

My goodness but this annual award section is fun. Every year as the model year ends and hints of the coming year begin to arrive, the staff and consultants sit down and fight over which bikes are best.

Big conference. We collect the desert crazies, the racers, our two cowtrailers, the touring nut, ol’ “Been riding since 1942,” the executive who has a cafe racer stashed in our warehouse, the British Twins (one owns a BSA, the other a Triumph. We can’t tell them apart). As you’d guess, we have a wide range of opinions and feelings about what motorcycles are supposed to do and which ones do it best.

This is our second annual awards issue. We believe that the men who design and produce the modern motorcycle deserve some credit for work well done. This is how we do it.

The rules are simple: Draw up 10 classes for type and usage of motorcycle, based on general characteristics or actual competition rules. List all the makes and models currently in production or on sale, which we’ve tested in their present form. Divide this giant list into the various classes. Finally, vote on which bike is the best in its class.

The results are on the following pages. If you’re like us, you’ll look first at the results, especially in the class or classes into which your machine has been assigned. You’ll then agree with us or not. (Usually, if you’re like us, your reaction will depend on whether your bike won or not.)

Short pause for everybody to look at the results.

Fine. Constant readers will notice some changes in the classes. The road bikes are no longer divided on the basis of engine displacement. We did this because the makers have blurred what formerly were distinct categories. Where we once had 350cc, 500cc, 750cc, etc., now there are 360s, 400s, 550s, 860s and such. Therefore we’ve used the size and weight of the machine, along with approximate engine displacements, to assign each model to a class.

TThe competition classes remain displacement based, just as the racing rules do. The trials class has been dropped, because there has been so little news about trials machines during the past year. There’s now a dual-purpose class, because there have been several new models and developments in that field.

To be considered for any of these awards, a motorcycle must be sold in the U.S., to the general public. It must be in production or still in the pipeline. It need not have been tested this model year: Several class winners were not tested during the 1977 model year because they were virtually unchanged from the previous year. With reason, as they are still the best in their fields.

To risk explaining the obvious, the motorcycles considered for the awards must have been available to us. There are makes and models we haven’t been able to try. They may be fine machines. There may be reasons we cannot obtain them for test.

Another new feature for the annual awards is the honorable mention. This isn’t the same as 2nd place. In class after class we found debatable points of view. Sheer speed, perhaps, vs performance per dollar. Or an all-round model with routine looks vs a bike with dramatic impact achieved at the expense of daily use.

When this occurred, we felt the minority viewpoint deserved credit of its own and majority rule be damned.

If one idea ruled the discussions and voting for the Ten Best, that idea would be value. Not price. We can all think of bargains that aren’t worth buying and of expensive things which are overpriced by any standard. Value, though, is when your money is well spent, when you get what you pay for.

Motorcycles are better than ever. Here are 10 motorcycles which we believe to be better than the rest.>

TOURING

Honda’s flagship caused a bit of a stir when it was introduced. From conventional 750 to a water-cooled 1000, opposed Four, shaft drive, dummy fuel tank and all the rest seemed like a lot of change all at once. Soon as the shock wore off. though, and the touring riders had a chance to learn just how nice it is to cruise for hours in smooth silence, they began buying the GL in large numbers. By the end of the 1977 model year, seemed like every other bike you see on the open road is a GL with fairing, bags, CB radio and two relaxed people.

Honda’s planners saw this coming. The GL is a complex machine. Critics contend the GL’s number of systems, that is, all those pumps and circuits and thermostats and rheostats make the Gold Wing more like a two-wheeled car than a motorcycle. Something in that. The GL is complicated and Lord knows it surely is big.

The defense is that the systems work. The low gearing and water cooling and mild engine and low center of gravity all mean the GL will run hard and run fast and apparently will run forever. During the model year we had three of the friendly giants in and around the office, for road tests and evaluation of various add-on items and the GLs always went on and on with a minimum of care.

The suspension isn’t perfect and the factory could usefully provide more loadcarrying capacity, especially in back, but that can be taken care of by the owner at reasonable cost. Make the changes you want, buy the touring gear you like and you’ll have the best touring bike on the market for the money.

HONORABLE MENTION BMW

BMWs are something of an acquired taste. First time the average rider gets on a Beemer, he comes back puzzled. There’s nothing wrong, exactly, but the BMW is so, well, so different.

The BMW is for the experienced enthusiast. The suspension and brakes and controls are the best in the world. The BMW is the finest combination of speed and comfort and handling and reliability offered. What keeps the BMW line out of first place is simply the purchase price. The functional gap between Honda’s GL and the 900 or lOOOcc BMWs isn’t as wide as the difference in cost.

SUPERBIKE

Judging superbikes begins with solid facts. Look back at the road tests of all the bikes for the past year and there's the KZ1000, quickest of the year. Quickest production model we’ve ever tested, in fact, so the KZ1000 began as the leading contender.

That’s were it stayed. There’s more to life than the Stoplight Grand Prix. Not only is the KZ1000 quicker than the others, at the same time it’s large enough for touring, quieter than a Sierra Club picnic and the engine is mildly tuned so milesper-gallon makes the oil-producing countries worry.

None of this is an accident. The first Kawasaki Zl was a road-rippler, a bigger, four-stroke version of the fabled twostroke screamers which earned the factory a reputation for lots of power and handling that was sometimes more than the rider could handle. With performance established, Kawasaki moved into related fields, like brakes and suspension and frame design. The KZ900 was an improved version of the Zl, and the European versions had good stuff like stronger brakes and steering head gussets.

The KZ1000 takes advantage of these lessons. And when the factory made the

engine larger, the tuning and gearing could be dialed back a couple notches. The power curve is higher and flatter, mpg has improved and noise is reduced, so much so that at steady and legal highway speeds, the loudest noise comes from the tires. (Try that on your H2.)

Speed isn’t everything. With the ZeeThou, Kawasaki has taken a good model and made it better, while not subtracting any of the good parts.

HONORABLE MENTION HARLEY-DAVIDSON XLCR

Sheer gut pleasure. The XLCR is a limited production version of the Sportster; alloy wheels, double disc brakes, a revised rear frame section at least based on the flattrack XR750 racer and a Siamesed exhaust system, all topped by a stylish cafe-version tank, rear fender and bikini fairing.

Deep down, the XLCR is a Sportster, not quite as quick as its sounds, not as comfortable in the fast stuff as the looks promise and something of a handful around town.

The XLCR is not a technical triumph. What it is, is fun to ride and be seen on and we couldn’t let such a wonderful toy go unrewarded.

HEAVYWEIGHT ROADSTER

When Suzuki entered the four-stroke wars, the entry was done right. At least one rival retreated in confusion as the top of Suzuki’s line, the GS750, set new test records on all sides.

The approach is conventional. The GS750 has a long wheelbase, so there’s room for two people and the bike runs straight as an arrow. The frame is strong. Never during our test, which finally took us and the GS750 to a race track because we couldn’t assess the model’s handling potential on public roads, did the bike give any cause for worry. Not only is the new four-stroke more than a match for the twostroke big bikes of yesterday in terms of sheer speed, but the GS has a chassis and brakes to match its power.

Suzuki engineers cheerfully agree that their 750 looks mighty like Kawasaki’s range of inline Fours. The specifications are also alike, as both brands use doubleoverhead camshafts, large valves, oversquare bore/stroke relationship for more power at higher revs. It wasn’t a matter of copying, the Suzuki men say, it’s just that this is the best way to build a good engine, no matter if other people did it a few years earlier.

The GS750 has everything. Quick enough to win at the drags, 40 miles-pergallon in daily use, room for two people and their gear, handling for Sunday roads or pure-stock road racing, all while humming along as quiet as your aunt in church.

Being fair about this, our testers thought the shape of the handlebars was a bit odd, the seat a bit stiff. Suzuki threw in a few gimmicks, like a digital speed indicator and red instrument lights, both of which take some getting used to.

Not much criticism, then. Suzuki’s GS750 does nearly everything better than its rivals. Simple as that. Or to use our internal evidence, the GS750 was so clearly the best of its class that there is no honorable mention. Nothing else in class got mentioned at all.

MIDDLEWEIGHT ROADSTER

One of Kawasaki’s bonuses for ruling the rocketships is that when the firm needs another model to round out the line, it doesn’t need that model to be large. The KZ1000 already can meet the touring rider’s needs.

So when Kawasaki introduced a middleweight, the KZ650 by name, the new model could be a sporting model; 750cc’s worth of power in a 500cc-sized package.

The KZ650 is just what a lot of buyers wanted. Sales figures less than one year after the introduction show the sharp little roadster setting new records. By the end of its first year, the KZ650 looks to be the most popular new model ever. Yes, we’re counting the Honda Four.

What all those buyers are getting is a compact Z1/KZ900/KZ1000. The basic engine design is almost exactly the same, but while Honda and Suzuki need to keep their mid-range bikes safely below the 750cc biggies, Kawasaki could use 650cc and have more power. With extra displacement they could tune for a strong low end, which means that while KZ650 runs in the low 13s at the strip, it also pulls strongly in traffic, with no need to wind the engine into the red.

The compact chassis comes into its own when the curves begin. The 55-in. wheelbase gives agility. The steering rake is on the steep side, with just enough trail to keep the front wheel from following bumps, while both settings mean the rider can lean into the curves and whiz through without wrestling the bike down or having it fall toward the inside.

The KZ650 was another uncontested winner, in that no other bike in the middleweight class came close. To back that up some, a KZ650 is presently in our shop, as a long-term test and project bike. No matter what other road bikes have been on test, when it’s time for going places, the man who draws the winning straw always rides the KZ650.

LIGHTWEIGHT ROADSTER

Too bad we don’t have access to Yamaha’s innermost secrets. Sure would be fun to know if the men who make the RD400 had any idea in the beginning what they’d do to the motorcycling world.

When the RD350 arrived not long ago, the slick little two-stroke Twin was so much swifter than the average little roadster that the owners took their new toys to the race tracks. And won, not just in class but frequently against bikes with twice as much displacement. The RD350 set new standards for road-going rockets, both for speed and for handling.

The RD400 replaced the 350, with more power, a few more pounds and all the sporting virtues of the original. The 400 was the quickest in class and kicked sand on more than a few 500s. We were so impressed with the RD400 that the test said—poetic license backed by the figures— that only the feeble horn kept the RD400 from being the perfect motorcycle.

The 1977 version was virtually unchanged from the ’76 and we didn’t test the latest RD400. But when it came time to vote, the RD400 was an easy winner, never mind that both Honda and Suzuki have all-new models of the same size and intent.

The RD400 is the most sporting model in the field. At the same time the price is competitive and the RD400 will do all the normal things, like go to and from work, run errands and like that, as well as the others.

HONORABLE MENTION HONDA CB400F

Speaking of leaving the market, Honda’s officials are grudgingly admitting that it looks like the 400 Four won’t be with us next year. Not enough demand and it costs too much to produce and it’s too complex for people who’re just getting into bikes.

For shame. The 400F looks just right and it’s such a nimble little rascal we’ll hate to see it go. Hint: Last time headquarters decreed the demise of the little Four, dealer demand kept it in the catalog.

ENDURO

Surely the most quantum jumps in motorcycle progress in the past year have been in the field known as enduro bikes, whether that translates as competition machine or good equipment for the fun rider.

Honda began edging close to the ideal, and the Yamaha IT’s got every virtue except steering. Suzuki’s PE250 was the best mass-produced enduro ever, and a few short months later the newest Yamaha IT, with 175cc engine in the case of our test bike, blew ’em all away.

Wow. The days of the $2000 serious dirt bike and the $1000 pseudo bike are over. For the IT, Yamaha took cooking versions of the motocross engine and suspension, reworked the front forks to give steering control as good as any in the world and threw in a few extras like odometer/speedometer and a tool bag. For less than $ 1000 list. Again, wow.

The IT 175 has something for everybody. One of our experienced off-road riders took the test machine into the desert and kept up with the best in his club. Two novices rode the IT 175 on exploration trips in the wilds and came back amazed. The bike did everything they asked and they didn’t put a wheel wrong in 300 miles of fast-as-you-dare.

The 175 engine is strong for its displacement, almost a match for the class bully Can-Am 175. The monoshock does well. Probably more useful here, the monoshock allows a really stiff swing arm and frame, so nothing gets forced out of alignment and the bike always reacts as the rider expects.

Not enough engine. If you weigh more than 200 lb., that might be a problem. So get an IT250 or IT400.

HONORABLE MENTION KTMIPENTON

Let’s be fair about this. While we pay tribute to the mass-produced enduro models providing specialist virtues for less money, and while the vast majority of motorcycle enthusiasts probably can’t use the tiny edge provided by the best of the true enduro models, still, the best of the specialist machines do have an edge.

For those favored few who can keep up with Malcolm Smith, Clark Cranke or Bill Uhl (or who are getting ready to try and damn the expense) motorcycles like the KTM/Penton, West or East Coast and we can’t stand trying to explain that again, do offer intangible advantages. Braking precision, the last little bit of traction when you need it most, steering that reads your mind, make the KTM/Penton the purists’ best.

125 MOTOCROSS

The 125 class in motocross is mostly a youth market. There are some fully grown racers who like the challenge of squeezing full speed from a peaky little motor, but for the most part, at club level, 125 is where the lightweight rockets learn their trade. There have even been champions who had to move up to the 250s because they’d outgrown their mounts.

The young rider is brave. And skilled. He may even have a few years of minicycle racing behind him. With all this, though, you also find a racer who has to work on the bike himself, and pay for the parts with his own money. To make it more difficult still, 125 racing is so competitive that a stock machine seldom wins. The guy in 1st place always seems to have this week’s swing arm or shocks or pipe to give a two percent advantage over last week’s hot item.

So we picked Suzuki’s 125, not entirely for sheer speed, although the RM 125 is fast, but because it’s the best raw material.

The limited-edition 125 racers from Europe are ruled out in this class because of cost. Honda and Kawasaki are supposed to have new racing models next year, which tells you plenty about this year. The Honda Elsinore was the most popular 125 for so long that it has the longest list of available aftermarket options, but by late 1977 not all the add-on goodies in the world are enough to assure a class win with a Honda.

What we come down to is a choice of two, Suzuki and Yamaha. (We’ll see this choice twice more, by the way.) Both Suzuki and Yamaha have good basic engines and good overall design. The RM has the best front end and brakes. The YZ may have the best frame and rear suspension, thanks to the the monoshock’s inherent concept, but tuning a conventional pair of rear shocks can be done more easily, at less cost, and with a better chance of coming up with the combination that’ll work at this track on this day.

In short, if we were tough, light and brave enough to tackle 125 motocross racing, we’d begin with an RM 125.

250 MOTOCROSS

Yes, a tie. That’s the way the voting went on the first ballot and that’s how the matter was resolved after debate. Even though elsewhere in this issue is a rave review of the RM250C, during which we took the stock test bike to a local track and won both motos against good riders, we’ll divide this one down the middle.

The 250 class is our favorite. Enough beans to give an adult a shot at the winner’s stand, not enough surplus power to scare the prudent, i.e. the members of the staff not brave enough to roll an openclass bike all the way on.

As with the 125 racers, the European models do come complete and they are mighty good. But for the money, in terms of value as defined earlier, the low-volume factories must charge a lot for their products and even after making the modifications needed to be competitive, the massmarket racing bike is as fast for less money. We enjoyed the KTM 250 and the Can-Am 175 this test year but until they get a clear advantage for the price, we’ll stick with the bargains.

And again as with the 125 class, the RM and the YZ are fairly close in price and in specification and in power. The RM seems to have a better front suspension, while the rear shocks and springs probably will need replacement with something a bit better. The YZ’s tunable monoshock works well on a wide variety of tracks and for riders whose styles differ markedly. The RM’s shocks work well and can be replaced if they don’t.

In short, a tie. Well, right at this point the YZ probably does have an edge. We’ll disregard that, though, because the motocross wars are so fierce and the models come so quickly that by the time this appears the newest RM may be introduced and the scale will tip back the other way.

Meanwhile, while we can’t say you can’t lose with either an RM or a YZ, if you have the talent, you can win with either model.

1976 MODELS

OPEN MOTOCROSS

At the beginning of this class discussion a few timid remarks were entered to the effect that there are other bikes in open class motocross than the Yamaha YZ400. Said remarks were offered because none of the testers or consultants who had ridden the test YZ or ride privately-owned examples had anything to say except how good Yamaha’s cannon is.

The test was extensive. The latest model monoshock is tunable at trackside. fore and aft. The offset forks can be adjusted in minute degree, thanks to the factory’s complicated use of springs in compression and tension, or oil as both a damping medium and a spring rate adjustment, and of air pressure as the final touch. Spring preload on the monoshock and the internal damping rates of Dr. DeCarbon’s latest project also can be changed, by the private owner in the pits. The mild steel frame is hell for stout and if—as mentioned elsewhere in this issue—the production swing arm has proven to be less than perfect, that offending member can be cast out and an aftermarket arm will put the YZ400 right back into contention.

This year’s 400 engine is basically a racetuned and stripped version of the Yamaha’s across-the-line Single. The six-petal reed valve keeps the 400 strong on the low end and allows a 38mm Mikuni carb for good power on top. Impromptu drag races with most of the open class models from elsewhere, and with one 500 Single as well, showed the Yamaha engineers didn’t exaggerate when they said they’d never lost a dynomometer duel with any 400cc engine on the market.

That the YZ400 wins races isn’t a question. Check the results, from your local track all the way to the world title race, in which Roger DeCoster has just conceded he can't catch Heikki Mikkola.

What makes the YZ400 best is the how and why. The design is so right and the details so adjustable that the bike can be ridden fast and quickly no matter what the rider’s style. The YZ will bounce off berms or tuck to the inside. It will do what the rider wants. Including win.

DUAL PURPOSE

Bit of a fudge, this. The winner of the class for 1977 is officially listed as a '78 model, mostly because the motorcycle sellers have decided the car people have a good idea there. But the DT125E did arrive in the 1977 calendar year, October to October in magazine terms. And the DT125 is the best dual-purpose bike out.

The pragmatists here are enjoying this a lot. The guys with a family car and a truck and touring bike and sports bike and dirt bike pretend not to understand how the man with one motorcycle can ride it in the woods and on the highway.

The DT125 comes close to making believers out of purists. The DT is light, so it's agile. The DT benefits from all the feedback coming out of Yamaha’s motocross and enduro team programs. The nifty little engine will start on the first kick and provided the rider rows briskly through the gears, the 125 will carry him or her all the way to legal highway speeds without hazard. Fully legal in all states, of course.

When the pavement ends, drop tire pressures and the DT has enough bite to get through almost anything. Steering is adequate, the gears are spaced right and even desert flyers didn’t bottom the suspension on the jumps and cross-grain. You can take the DT anywhere and by the time the new rider can ask for more than the DT will deliver, he’ll be a good rider indeed.

HONORABLE MENTION YAMAHA XT500

An exception here, in that the DTI25 won the vote and the XT500 came in second. The intent was to distinguish between runners up and a difference in design philosophy.

The XT500 gets the mention because along with coming in second, it does offer a difference in philosophy. The XT500 is your classic thumper, a 500cc four-stroke Single, heavy as your mother-in-law’s dumplings. Strong, though. The XT will run through traffic all day and never breathe hard. Makes a good road bike, in fact, so good owners are converting them for sole purpose.

Trouble is, the dual-purpose class has historically been for new riders and the big, strong XT500 can be too much for the newcomer. In tight going it’s a touch clumsy. A beginning rider with a heavy hand could get himself in trouble. Ergo, no first place.

But the XT500 is the best bike ever for luring experienced riders back onto the dirt.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontOn Messing About With Motorcycles

October 1977 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1977 -

Departments

DepartmentsService

October 1977 By Len Vucci -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

October 1977 -

Competition

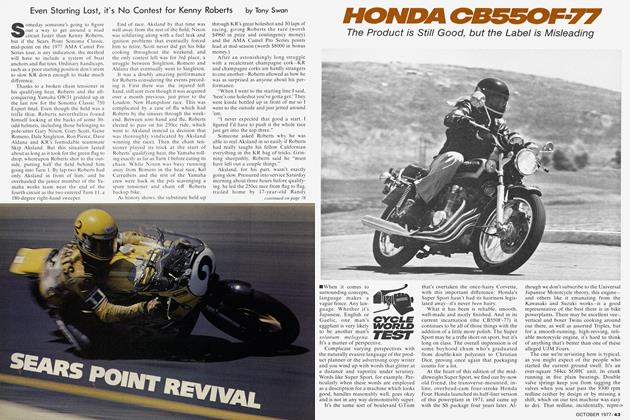

CompetitionSears Point Revival

October 1977 By Tony Swan -

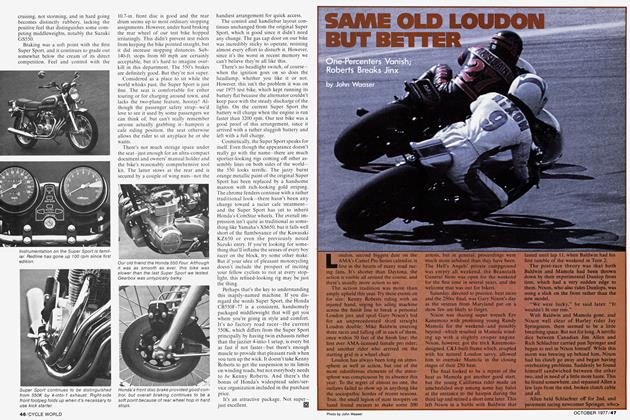

Competition

CompetitionSame Old Loudon But Better

October 1977 By John Waaser