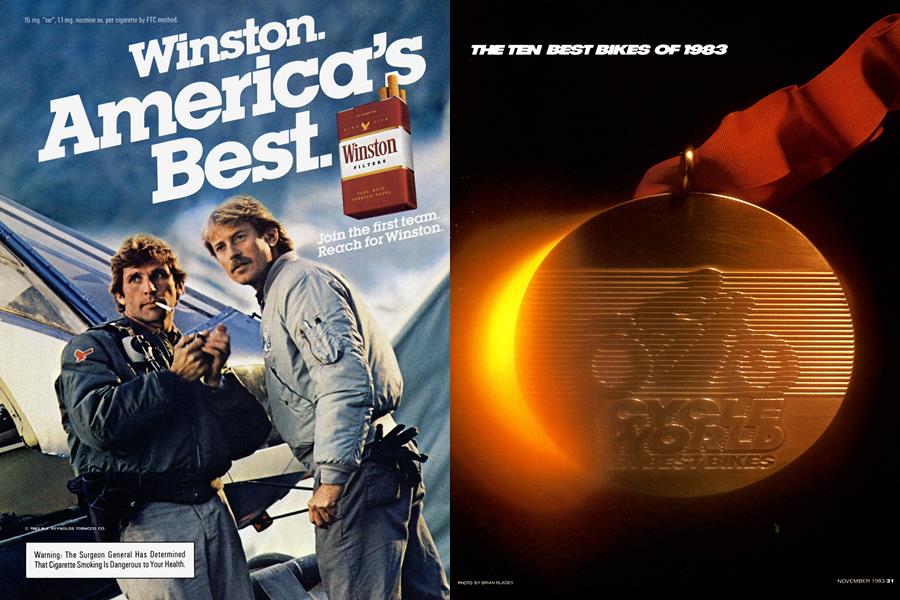

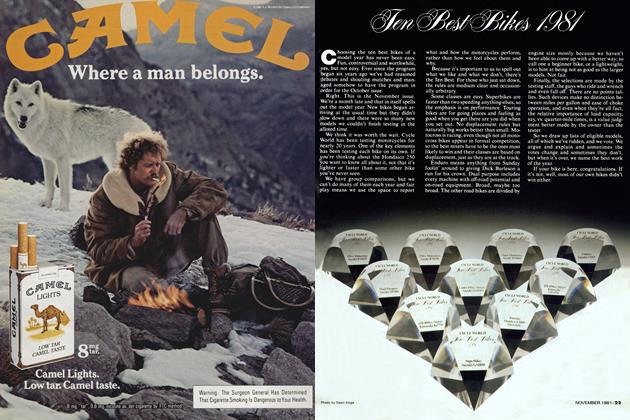

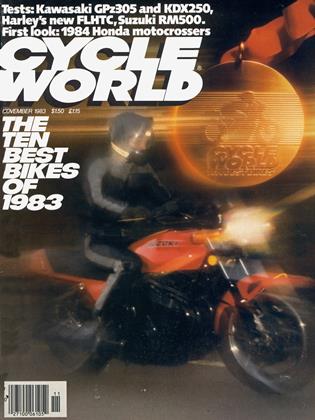

THE TEN BEST BIKES OF 1983

This is not as easy as it looks.

At about this time every year, we pause, sit back and reflect upon the 60-or-so bikes we’ve ridden and wrenched and tested (and, sometimes, crashed and broken) to bring you the preceding 12 issues of Cycle World. Then we come up with our list of the Ten Best Bikes.

Sounds easy enough, picking 10 out of 60 contenders. Truth of the matter is, it’s really the toughest thing we do around here.

There are several reasons. First is the state of the market. Motorcycling has entered the age of specialization; there’s a bike for almost every purpose conceivable. For any given type—or style—of riding, there are at least a couple of bikes that fill the requirements. Usually, there are more. This year, we figured, there were 200-plus models offered to the public. An incredible number.

And not one of them, could you call a bad motorcycle. Each had its strengths. Not in a single case did the cons outnumber the pros. There were major improvements in performance, in handling. Technological advancements came fast and furious; we saw new engines, new frames, even refinements to the venerable V-Twin. There were bikes that motorcyclists of 10 years ago wouldn’t have thought possible, never mind dreamed of. Obviously, though, some of the bikes had more merit than others—which is why we’re gathered here today, more about that in a minute.

Not only did manufacturer compete against manufacturer. Different models of the same make sometimes went directly against each other. Take the Honda 750 V-Fours, available in three flavors: cruiser-styled V45 Magna, sporty V45 Sabre and road-warrior V45 Interceptor. One engine, three very different bikes. To muddy the waters even more, Honda has two more 750s, the parallel-Four CB750SC Nighthawk custom and the V-Twin VT750C Shadow cruiser.

Then, there was the price overlap. An example: a 550 Twin (the Yamaha Vision, at $3299) that cost more than a 750 Four (the Kawasaki KZ750, at $3099).

What to make of all this? Just that there were a lot of very different bikes out there. That there were a lot of good bikes.

And that, sometimes, it was kind of confusing.

The selection of motorcycling’s top 10 is made even more difficult because, well, because we take it so seriously. Cycle World is the only motorcycle magazine that annually recognizes the best of the ten classes. And, we’ve been doing it for eight years now, so there’s a certain tradition about it all. Our awards are the Emmies, the Tonies, the Grammies, the Oscars of the sport. These are the Academy Awards of motorcycling.

How do we goubout picking the best? We consider only motorcycles thát are in current production, and available in the U.S. Each eligible model must have been tested by us. We assign the bikes to one of the classes. Voting is entirely by the magazijr^’s editorial staff, the folks who ride the bikes and write the te^is. When judging the contestants, we look at a lot of thirds: performance, braking, comfort, reliability, carrying

Jacity, passing and pulling power, cruising range, price. We > consider a couple of subjective, but important, things: feel, how well the bikes perform their roles. Then, we tabulate the is. On occasion, we argue. Eventually, we arrive at Cycle wurld's Ten Best.

So it’s a tough task. So we sometimes disagree. So we take it seriously. Enough. We know why you’re all here. Without further adieu, welcome to Cycle World's Eighth Annual Ten Best Awards.

451-650cc Street YAMAHA 550 VISION

Let’s get something on the record here. Performance, especially when you get out of the mega-displacement classes, isn’t everything. There’s also something known as feel. You could call it the pleasure quotient. As in: how enjoyable is the bike to ride?

In the case of Yamaha’s Vision 550, very.

When the Vision was introduced for 1982, we were impressed. The watercooled, eight-valve, 70° V-Twin shaftie was smooth, peppy and spry. Compact and light and economical enough for crowded city streets, powerful enough for the open road.

It had a few drawbacks, though. The suspension wasn’t quite right and couldn’t be adjusted. Braking wasn’t what it could’ve been. There was a bit of a troublesome flat spot. And the engine, as wonderful as it was, looked like something out of the International Harvester catalogue.

So, for 1983, Yamaha sent the engineers back to the drafting board and the designers back to the drawing board. The result was, well, a new, new super do-anything bike.

Gone was the flat spot. Gained was a strengthened engine. A tuneable suspension. A second front disc brake.

An attractive, highly effective fairing, with windscreen and lowers.

The Vision might not be the fastest or the flashiest in the class. But nothing else feels quite as right, quite as good, quite as fun.

Superbike SUZUKI GS1100E

If this was a presidential race, there’d be all sorts of clamoring for a 22nd Amendment, to limit the title to two terms. But it’s not, there isn’t, and a Suzuki GS1100 collects a third Superbike Award.

This year, the GS1100 came in three guises: the GSI 100S Katana, with its futuristic, land-shark bodywork; the Formula One-influenced GSI 100ES; and the GSI 100E, our pick for Superbike of the Year.

The E-model is almost understated, less radically styled than the other GS1100s: no fairing, higher bars, a round headlight. But it comes with the same 16-valve afterburner of an engine that hurled our test rider, aboard an ES, into the 10-second bracket at the dragstrip. Some other numbers, equally as impressive: 108 bhp, 0-60 mph in 4 sec., a top speed of 140 mph. Simply put, they’re the quickest bikes around.

All of the GS1100s are sturdy and reliable. They’re nimble. They stop well. They go like F-16s.

But most of all, the GSI 100E is a bike you can ride fast. Very fast, which, when you come down to it, is exactly what a Superbike is supposed to be.

651-800cc Street HONDA VF750F INTERCEPTOR

This category is the real front-line battleground of motorcycling. It’s home to inline Twins. V-Twins. Inline Fours. V-Fours. Turbos. Cruisers. Customs. Sport-tourers. All-out sport bikes.

And then, in a class by itself, the Honda VF750F Interceptor.

In a way, we should have seen it coming. The Interceptor shared the 748cc, water-cooled, torquey, 90° VFour engine found in the two-year-old V45s, the Sabre and Magna.

Then again, who could’ve dreamed of such an incredible bike a year ago? The Interceptor bowed in with an all-new frame, racy styling, an extra handful of horsepower.

This is a 750 with performance that matched—or bettered—that of some 1100s. It turns the quarter-mile in 11.67 sec. at 115 mph, and boasts a top speed of 132 mph. The power band is remarkably wide. Handling is superb. It’s no wonder that Honda Interceptors have been winning races since their introduction.

The Interceptor had some stiff competition in its maiden year. But, as we found in a heads-on comparison, it was the fastest. The quickest. The most powerful. The most dazzling.

The Interceptor ran the hardest, the best. - „

No contest.

Touring YAMAHA VENTURE ROYALE

An upset here. For some time, the standard for serious, full-dress, all-out touring has been the Honda GoldWing, in its Interstate and Aspencade garb. Exceptionally smooth, comfortable, durable, for years it was the only bike of its sort.

Until 1983 and the debut of the Yamaha Venture. Smoother, more comfortable, more powerful, equally durable. Now, there’s a new touring standard. It’s spelled Venture.

The Royale version is equipped with computer-controlled air suspension coupled to an on-board air compressor. And there’s an elaborate sound system, with signal-seeking AM-FM stereo radio, cassette tape deck, automatic volume control and intercom.

Touring has come to mean this: traveling wherever you want, whatever distance you want, at whatever speeds you want, carrying just about anything you want, reliably and comfortably.

Nothing is better suited for that than the Venture Royale.

Under 450cc Street KAWASAKIGPz305

For years now, this class has suffered something of a stigma. Bigger equals more power equals more fun, the feeling goes, and smaller equals less power equals less fun; small-displacement bikes are beginners’ bikes, commuter bikes.

Not completely true. Sure, the bikes in the lightweight class don’t have the performance of the mega-cc tiremelters. And since they’re generally small and light and inexpensive, they do make ideal bikes for commuters-

But toys? Less fun? Couldn’t be more wrong.

Take the Kawasaki GPz305, the best of the lightweight roadsters. You want to talk bulk, or lack thereof? The baby bear of the GPz family weighs 342 lb. That’s only about twice as much as an average rider weighs. Because of that, the 305 doesn’t have to be muscled through corners. Just a slight flick, a fast nudge, and the turn is history.

Light, smooth, breezy, neat. No big bike corners this effortlessly.

The best thing about this bike is that it’s not just a small bike. It’s a serious motorcycle born of two honest traditions: the sports GP bike and the high-speed hummers of the past.

And it’s proof that there are some things that small^ bikes do better.

Dual-Purpose HONDA XL600R

The adjective “dual-purpose” carries with it an implied connotation of sacrifice: to get a little of each, you have to give up a little of each. Sometimes, somehow, what you get doesn’t make up for what you lost.

In the case of Honda’s XL600, not true. It’s neither an underweight, underpowered street bike, nor an overweight, overburdened off-road bike, it’s a motorcycle that’s equally at home in both worlds. Some compromises, yes; sacrifices, no.

On the street, the XL600 is light and nimble. It steers quickly and stops well. Thanks to its marvelous four-stroke, single cylinder, four-valve radial-head engine, the XL600 has a surprising amount of power.

Off-road, the bike’s no slouch, either. There’s plenty of suspension travel, and the single-shock Pro-Link rear suspension has both adjustable rebound damping and spring preload. The XL600 is no enduro bike, but it’ll cover most rough ground with speed and ease.

On-road or off-roadTthe XL is very responsive. And, for a no-frills bike, it has some neat features.

Categories aside, what the XL600 is, is a damned good, all-around motorcycle, perhaps the most versatile thing ever on two Jh± wheels. jdV

Enduro HONDA XR350R

Welcome to the Wide, Wide, Wide, Wide World of Enduro. No other class has as varied a line-up of contenders. Two-stroke, four-stroke. Displacements ranging from lOOcc up to 600cc. Serious enduro racers and off-road playthings. Basically, any off-road bike that doesn’t compete in motocross ends up in this class.

Through the years, our Best Enduro Awards have gone back and forth and up and down the line-up. In 1979, the honor went to a 175. Three years ago, the award went to a 465. The last two went to 250s. Little rhyme or reason? It might seem so, but that’s not the case. Usually, one bike stands out.

This year, that bike is the Honda XR350R.

The newest of the new dirt bikes, the four-stroke XR350 has, pardon the cliche but it’s true, big-bike power and small-bike agility. The radial-valve head deserves much of the thanks for that; it’s short, narrow, compact and light. Power is plentiful. And strong.

Suspension is excellent; steering is quick. The six-speed gearbox is smooth, and offers a selection of ratios that*ll keep the engine in the strongest part of the power band on any terrain.

For the enduro set, the XR350 is a deadly serious competitor, a four-stroke that will take on the two-strokes. For the weekend pleasure-riders, it’s just plain fun.

125cc Motocross HONDA CR125R

A year ago, we did a comparison test of the Big Four’s 125 motocrossers. All were water-cooled. All were two-stroke Singles. All had six-speed transmissions, strong steel frames, single rear shocks. Pretty much alike, even in performance.

Where they differed was in how well the components fit together, how well the package worked. In the case of the 1982 Honda CR125, not very.

Now, a year later, the 1983 Honda CR125R comes along and picks up the gold. This was more than a face-lift.

This was a metamorphosis.

The ’82 model had a lot of power, but it was all at high rpm. In low and midrange, it was a slug. The seat was so high that it was hard to ride.

Honda’s engineers went back to work. There were modifications to the engine, transmission, frame, suspension.

The 1983 CR125R came with added torque and an increased power band. A lower seat, by 2.5 in. A new frame, with new steering geometry. A new rear shock, with 20 rebound and 12 compression damping adjustments.

Gone was the lowand mid-range laziness. The awkward feel. The lack of tuneability. Gained was power.

Stability. Manueverability. The CR125R improved so much that it outdistanced its competitors.

Last year’s caterpillar M*» becomes this year’s ;

butterfly. AÆ/V

Open-Class Motocross HONDA CR480R

Open-class motocross is the macho grande of off-road competition.

The biggest engines. The most power. The highest speeds. The bikes? Well, we’re talking superbikes with knobby tires. Sheer power, monster performance. That’s the name of this game.

This year, the fastest and best of the dirt rockets was Honda’s CR480R. It’ll flatten hills, pave gullies, shorten straights and humiliate opponents.

That brute force comes from a big 472cc two-stroke engine. For 1983, Honda ported the engine, and modified the ignition and exhaust to give the big single a new infusion of power in lowand mid-range. The new-muscled CR outran bikes with larger displacements.

The CR480R handles as well as it goes. Most open-class bikes feel heavy, cumbersome. Not the 480. At 236 lb., it’s light, responsive, quick to react. It doesn’t take much effort to flick it through the tightest of turns, and quickly.

An excellently spaced five-speed transmission and 12-way adjustable front forks are just icing on an alreadydelicious cake.

Open-class motocross is one mean class. The Honda CR480R is the meanest of the class.

That makes it the meanest of the mean. Nothing else on two knobbies is a match.

250cc Motocross HONDA CR250R

If we had to pick the best dirt bike of 1983, it’d be Honda’s water-cooled CR250R. It handles like a 125. It goes like a 360. It’s narrow, light, quick, nimble. It’s the closest thing we’ve seen yet to the perfect motorcross racer.

The 1982 CR250R was long on major changes, but short on refinements. There was potential there, but, well, things just didn’t quite mesh.

The refinements came in 1983. A new frame, with a unbolting rear section. New cylinder and head. Some engine massaging. Gearing changes. A new rear shock, with 20 rebound and 12 compression damping adjustments. Alterations to the brakes and hubs. Weight reduction, 10 lb. worth: the bike now weighs in at 226 lb.

Was it worth the wait? And how!

There’s power from idle up, and it goes a long ways up. Cornering is nothing short of fantastic. The CR250 is well-balanced and agile and quick to respond. It easily swallows up the roughest of terrain. The brakes are strong and controllable. It’s easy to ride.

The 1983 CR250 cashed the check that last year’s CR wrote. It’s one of those all-too-rare bikes that seems to exist in perfect harmony. There is nothing that we’d change. The bike is competitive just the way it comes.

Take the CR250R otit of the crate. Gas it up, oil it up; Start it. Then hit the track and win.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

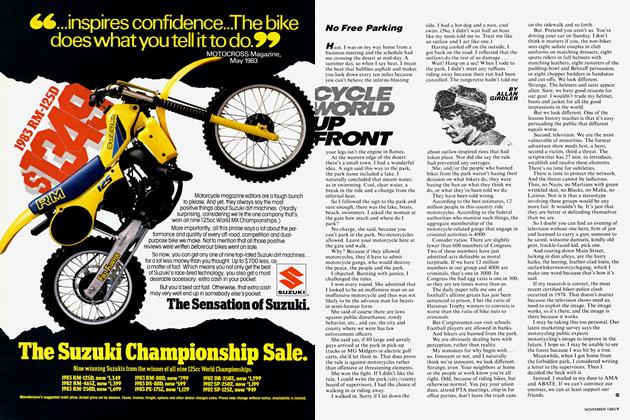

DepartmentsCycle World Up Front

November 1983 By Allan Girdler -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

November 1983 -

Departments

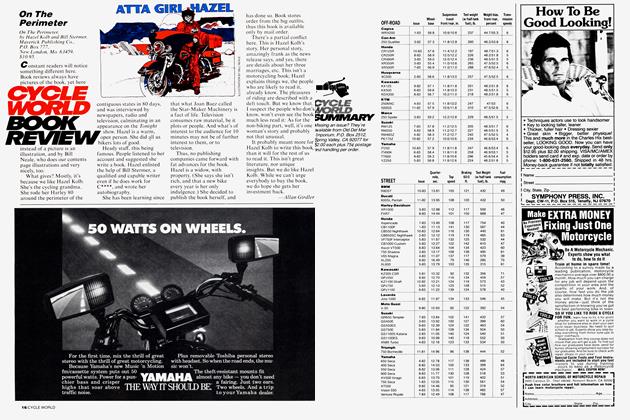

DepartmentsCycle World Book Review

November 1983 By Allan Girdler -

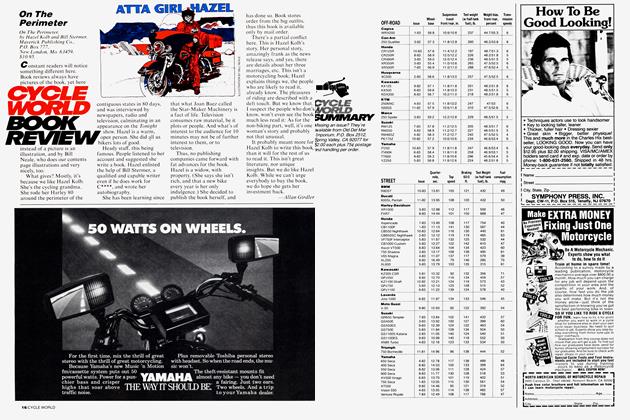

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Summary

November 1983 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

November 1983 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

November 1983