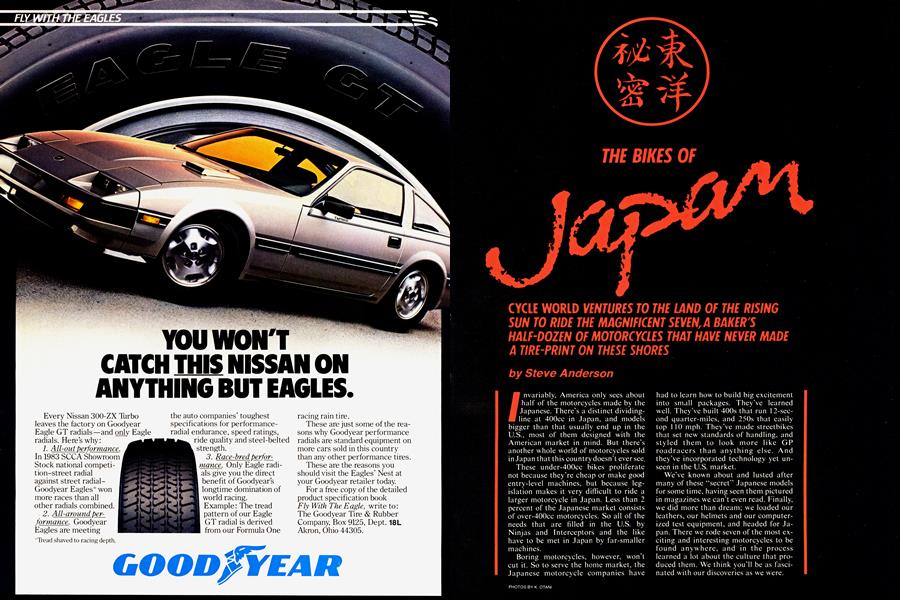

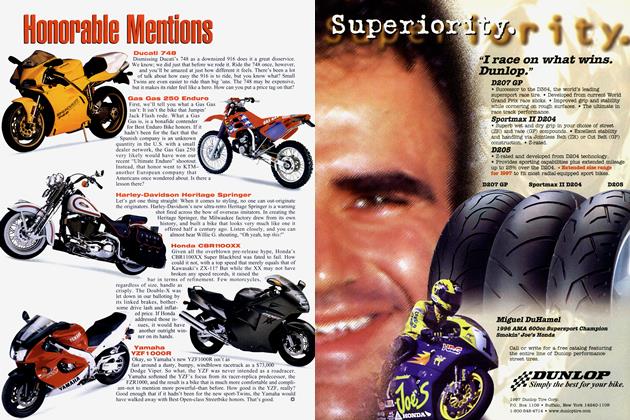

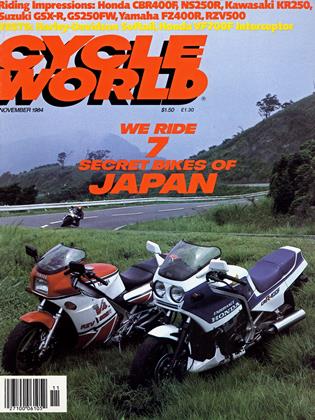

THE BIKES OF JAPAN

CYCLE WORLD VENTURES TO THE LAND OF THE RISING SUN TO RIDE THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN, A BAKER'S HALF-DOZEN OF MOTORCYCLES THAT HAVE NEVER MADE A TIRE-PRINT ON THESE SHORES

Steve Anderson

Invariably, America only sees about half of the motorcycles made by the Japanese. There’s a distinct dividingline at 400cc in Japan, and models bigger than that usually end up in the U.S., most of them designed with the American market in mind. But there's another whole world of motorcycles sold in Japan that this country doesn't ever see.

These under-400cc bikes proliferate not because they’re cheap or make good entry-level machines, but because legislation makes it very difficult to ride a larger motorcycle in Japan. Less than 2 percent of the Japanese market consists of over-400cc motorcycles. So all of the needs that are filled in the U.S. by Ninjas and Interceptors and the like have to be met in Japan by far-smaller machines.

Boring motorcycles, however, won't cut it. So to serve the home market, the Japanese motorcycle companies have had to learn how to build big excitement into small packages. They’ve learned well. They've built 400s that run 12-second quarter-miles, and 250s that easily top 1 10 mph. They've made streetbikes that set new standards of handling, and styled them to look more like GP roadracers than anything else. And they’ve incorporated technology yet unseen in the U.S. market.

We’ve known about and lusted after many of these “secret” Japanese models for some time, having seen them pictured in magazines we can’t even read. Finally, we did more than dream; we loaded our leathers, our helmets and our computerized test equipment, and headed for Japan. There we rode seven of the most exciting and interesting motorcycles to be found anywhere, and in the process learned a lot about the culture that produced them. We think you’ll be as fascinated with our discoveries as we were.

PICKING UP WHERE THE RACE TEAM LEFT OFF

With the stoplight about to turn green, our guide through Tokyo looked back and winced. He was unnerved by the raspy wailof the KR250 behind him preparing to launch away from a traffic light at 8000 rpm. It was a racetrack sound, out of place in most cities. But in Tokyo, even the taxicabs come off the line hard. And to stay ahead of traffic and keep up with our guide’s quick and torquey Yamaha RZV500, the peaky Kawasaki demanded dragstrip starting techniques.

Indeed, one way or another, the KR250 brings out the closet racer in the most conservative of riders. That’s its heritage. Three years ago, Kawasaki won a world championship with another bike named KR250. But while the street KR owes its basic design to the racer KR, the two share no parts. Both have at their heart a twin-cylinder two-stroke engine that is, in effect, two 125cc Singles mounted one behind the other in a common crankcase, their cranks connected by large gears. Rotary-valve induction is used on both racer and replica, with dual carbs feeding into the side of the crankcase. An exhaust pipe from the front cylinder tucks under the engine; the other pipe snakes its way from the back of the rear cylinder toexit high nearthe seat. Both KRs are narrow, light and powerful.

That racer heritage shines through in the street KR250. The engine pulls cleanly everyplace, but it’s happiest between 8000 and 10,500 rpm. When the engine hits eight grand at full throttle in first gear, the front wheel claws for the sky while the KR leaps forward almost as quickly as a catalyst-equipped RZ350 Yamaha. And the Kawasaki cruises smoothly and effortlessly at speeds unheard of for a 250: 80, 90, 100 mph. Top speed is well over 110 mph. The penalty is that, much like a racing 250, the KR only makes good power in one gear at any given speed. Come out of a corner a gear too high, the engine will drone ineffectively. Handling-wise, the KR is quick-steering yet stable, and the suspension is supple over small bumps, rather harsh over large ones. The only real handling defect, however, comes from the slightly rearward weight bias: The front end lightens so much under power that the steering can be vague and imprecise when charging out of slow turns.

Still, for a thoroughbred racer that’s been tamed for street use, the KR250 has few weaknesses. It’s racy enough to be more high-revving fun on the street than just about anything on two wheels.

Kawasaki KR250

$2041

FORMULA TWO GOES COMMUTING

There’s a road in Japan, just two hours outside of Tokyo, that twists and winds through rugged countryside like a ribbon draped over a bush. The turns are tight and banked, the surface clean. And on this road, Honda’s NS250R is magic. It can brake deeply into the corners, bank through them at radical angles, and charge out like a forreal roadracer. On this road, the NS250R has no match.

Unfortunately, the bike has to be ridden to this magical road. And riding the NS in traffic can be as miserable as riding it on The Road can be fun.

The key to understanding the NS250R’s behavior can be found in Honda’s brief history with the 250cc two-stroke streetbike class so hotly contested in Japan. Honda first entered the market two years ago with the M VX250. a V-Three patterned loosely after Freddie Spencer’s 500cc GP racer. The MVX was pleasantly torquey for a 250, but not as fast as the competition. Nor did it sell as well. So Honda reasoned that if a torquey, civilized, not-very-fast twostroke wouldn't sell, the answer was to build the opposite—the NS250R.

Mechanically, the NS seems state-ofthe-art, powered by a 90-degree V-Twin housed in an aluminum chassis. The reed-valve engine incorporates some sophisticated technology, including Nikasil-type coated aluminum cylinders and an electric ATAC system (similar to the mechanical systems on Honda’s CR 125/250 MXers) on the front cylinder only. And in styling, the NS is an authentic replica of a real GP racebike, right down to the optional sponsors-decal package.

But not only does the NS look like a circuit bike, it behaves like one. Power comes in with a vicious kick at 8000 rpm, and the engine pulls hard right past the 10,500-rpm redline. And the NS can flick into corners with a quickness that makes the bike feel more like a grand prix roadracer rather than a street-going motorcycle.

Indeed, but the NS is a streetbike, and problems arise when it is ridden like one. It pulls smoothly but slowly up to 4000

rpm, and from there to 6000 it burbles and bucks. It smoothes out again at 6000, but still doesn’t pull with authority until it lunges forward at 8000 rpm. So in traffic, the rider has to choose between putting along at low revs while being passed by mopeds, or surging ahead in the powerband for a second before having to back off. And either way, the NR billows clouds of blue exhaust smoke.

Thus, the NS250R is a flawed gem. On a racetrack or the right road, it sparkles; but on the average street, it has all the glitter of a fouled sparkplug.

Honda NS250R

$2209

A 369-POUND, 400cc STRATEGIC STREET WEAPON

Twelve-second quarter-miles from just 400cc that's what you need to know about Suzuki’s GSX-R. It's a motorcycle designed to devastate the competition in Japan's highly competitive 400cc class. And in most respects, the GSX-R does just that.

Radical engine technology isn’t behind the GSX-R’s phenomenal performance. Its engine is conventional by Japanese standards a liquid-cooled, 16-valve, inline-Four that first appeared in Suzuki’s more-civilian GSX400FW. There, it made only 50 horsepower, so it required a boost before going into something as racy as the GSX-R. That boost was brought about through standard hot-rod techniques: larger valves, more compression, wilder cam profiles. The hop-up wasn't entirely the work of Suzuki's engineers; Pops Yoshimura, who has close ties with the Suzuki factory, helped in the prodding of 59 horsepower from 400cc.

But it's not engine performance that distinguishes the GSX-R from its competitors; it’s weight. The bike is a featherweight at 369 pounds, fully 75 pounds lighter than Honda’s CBR400F. Even a U.S.-model RZ350 is about two pounds heavier. The aluminum frame of the GSX-R is an aid to lightness, but only attention to detail fully explains the lack of bulk. A perfect example is the twin headlights, which use lightweight plastic lenses rather than heavy glass.

Light weight pays off in more than just acceleration. On the racetrack, the GSX-R is stable while being wonderfully flickable, a combination resulting from what would be slow steering geometry on a heavier machine. The engine is noticeably torquey as well, arousing suspicions that its 59 horsepower is measured only at the brochure, and that its designers knew that removing weight would improve the power-to-weight ratio with less compromise than would leaning on the engine excessively.

The GSX-R works nearly as well on the street as on the track, with a few exceptions. The brakes fade in hard use, and never completely come back, and quick stops call for high lever-pressures. The clutch suffers a similar fate in traffic, becoming grabby and making smooth riding difficult. Those are minor annoyances, though, compared to the toasting the rider’s upper body and hands get in hot weather. The blast of air from the radiator is hot enough to turn a pleasure ride into an endurance contest. Fortunately, Suzuki now offers ducts that direct this heat away from the rider.

Nevertheless, the GSX-R is a motorcycle that points the way to a new performance future, one where light weight is as important as ultimate horsepower.

Suzuki GSX-R

$2578

FOR A CHANGE, THE MOTOR ISN'T THE MESSAGE

for many motorcycles, it’s the engine that leaves an indelible impression, that engraves itself into memory. How could you forget the yowling CBX Six or the quaking torque of an XR1000? That’d be difficult, but it’s all too easy for the inline-Four engine in Yamaha’s FZ400R to slide from mind.

That’s not to say the FZR doesn’t leave its imprint. After riding it, you’re filled with wonder that any motorcycle can steer so precisely, so positively, and you’re left with a new standard for motorcycle handling.

A spec sheet doesn’t give a clue that the chassis, not the engine, is the center of interest for the FZR. The engine has all the trendy features: 16 valves, liquid cooling, a large bore combined with a short stroke. But in practice, the engine isn’t impressive. It pulls well at low speeds, goes slightly flat in the middle, then picks up again at the top of the rev range. It’s a perfectly usable powerband on the racetrack, but more midrange would be welcome on the street.

Looking at the chassis doesn’t fully build expectations, either. The frame is reminiscent of the FJ 1 100’s, with rectangular steel tubes wrapping around the sides of the engine instead of over the top. Tire sizes are the same as for the other 400s ( 16-inch front, 18-inch rear), and steering geometry is only slightly quicker (26-degree head angle and 4 inches of trail).

Whatever the difference, however, it tells you that it’s there the first time you whip the bike through an S-bend. The chicane at the end of the front straightaway at Sugo Circuit, for instance, can be taken at around 80 mph on a good streetbike. It requires hard braking, then a quick flick to the right and a hard flop to the left, with no time for a gradual transition. Every other motorcycle we rode at Sugo was work through the chicane, but the FZR sailed through so easily and precisely it left us wondering why we weren’t going faster.

This magical handling hasn’t come without a few penalties. The FZR does, after all, have a sticker on the side that says “Pure Sports.” The seat is thinly padded, if well shaped, and the suspension is stiff enough to make the wheels chatter on a bumpy road. Steering lock is about half that of other streetbikes, so a simple task like turning around in a driveway can be a chore.

Still, we’re willing to forgive the FZR far worse than these minor defects in exchange for handling that rivals that of GP machines. It leaves us wondering if the rumored FZ700R can be as good. And praying that it is.

Yamaha FZ400R

$2451

PERFORMANCE WITHOUT THE PAIN

In every way, the CBR400F Endurance surprises. It competes in a class filled with fierce sportbikes as uncompromising as a Ducati Pantah; yet the CBR is cushy and comfortable by comparison, without sacrificing anything but the last fraction of racetrack handling.lt gives away 75 pounds to the Suzuki GSX-R, but is only marginally slower. With the CBR, Honda has mastered the trick of having the cake and eating most of it, too.

With that weight disadvantage, the CBR400F can’t afford any power disadvantage as well. And although its aircooled, 16-valve, inline-Four doesn’t look special, new technology lurks inside the ordinary exterior, hinted at only by the REV acronym cast into the cylinder head. The REV system mechanically disconnects one inlet and one exhaust valve from each cylinder at low engine speeds, and sets them operating again at high rpm. This allows radical cam timing without killing low-speed power.

On the road, the CBR engine with REV lives up to its promise. At low rpm the engine pulls at least acceptably, and even better than that if the standard of comparison is the original Honda CB400 Four. Then, at 8500 rpm, there’s a leap in power that’s almost two-stroke-like as

all 16 valves go to work and send the CBR rocketing toward its 12,750-rpm redline. Amazingly, vibration is almost non-existant, with only a brief bit of buzzing between 5000 and 6000 rpm.

Handling on the CBR is solid, and it starts to feel slightly mushy and underdamped only at racetrack speeds. Motorcycles that work better on the racetrack don’t ride as well as the CBR, so the suspension is a very reasonable compromise for street use. The CBR’s 16-inch front wheel and quick steering geometry allow it to turn nimbly, but without sacrificing stability. No wiggles or wobbles here.

Sacrifice, in fact, is a word that’s not in the CBR’s vocabulary. Its seat is soft and well-shaped, the riding position is sport-touring rather than pure sport, and the fairing keeps the wind blast off the rider’s chest without bathing him in heat from the engine. The only discomfort comes from footpegs that are too close to the seat, cramping taller riders after a few hours on the road.

There’s a lesson to be learned from the CBR. It’s that the last few percentage points of performance are often purchased at a dear price. The CBR isn’t the quickest or best-handling 400, but it can deliver performance approaching 550class standards, and do it without pain.

Honda CBR400F Endurance

$2451

WELCOME TO THE SCHOOL OF THIMBLE-PISTON TECHNOLOGY

Every once in a while, some motorcycle company decides to find the smallest engine displacement that can be divided into four cylinders. Honda did it in 1973 with the CB350F, Benelli responded a few years later with its 250 Quattro, and now there is the Suzuki GSX250FW.

Suzuki’s little Four is a technical marvel of sorts. The four-stroke, doublecam, liquid-cooled, 249cc mini-motor has 44mm pistons traveling through a 41mm stroke. Just how big is a 44mm piston? Three of them could fit into a Honda XL600 cylinder without touching each other or the cylinder wall. But even engineers hell-bent for miniaturization couldn’t bring themselves to put four itsy-bitsy valves in a space well under two inches in diameter, so the GSX makes do with two valves per cylinder.

The rest of the motorcycle is more normally sized, scaled-down to about 90 percent of a typical 550. Shorter people fit it best, but even a six-footer isn’t cramped. The styling, which is reminiscent of an ’83 Suzuki GS750E, is only medium-sporty rather than effecting the pure racing look that is typical of the hot-rod 250s sold in Japan.

That’s okay, for this 250 doesn’t pretend to be a pure sportbike. It can’t. First, it weighs 398 pounds with a halftank of gas; that’s 30 pounds more than Suzuki’s own 400cc GSX-R, and 70 pounds more than the two-stroke 250s. Second, the tiny, high-tech Four simply doesn’t put out much power. Suzuki claims 36 horsepower at 11,000 rpm, which is substantially below the 45 bhp the two-stroke street racers all make. The non-impressive power-to-weight ra-

tio of the GSX leads to non-impressive performance, as indicated by its mid-16second quarter-mile. The GSX feels particularly gutless when pushed hard, requiring high revs without accelerating very briskly in return.

On the other hand, the GSX250 is a sophisticated, scaled-down sport-tourer for the rider not in a great hurry. It will eventually reach speeds of 90 mph or more on the open road, so it’s adequately fast there. When not asked to accelerate hard, the Suzuki loses its gutless feel, and the engine is as about as velvety smooth as anything with reciprocating parts can be. The chassis, which is far ahead of the engine no matter how the bike is ridden, delivers quick steering with big-bike stability. The seat is wellshaped and padded, and the bars and footpegs placed for long-range comfort. All in all, the GSX is the luxury 250 that offers four-cylinder looks and feel in the smallest Japanese multi yet.

Suzuki GS250FW

$1983

A GRAND PRIX BIKE WITH STREET MANNERS

Brutal. Peaky. Inhumanly fast. Vicious.

That seems to be what most people think the RZV5U0 ought to be like to ride. But what else could they think? The RZV is the closest thing in years to a street-legal replica of a winning 500cc GP racebike; and Kenny Roberts and his peers routinely complain that the GP bikes have gotten too fast and too hard to ride.

But that’s not how the RZV is at all. It is a very fast motorcycle that is closely related to Yamaha’s GP machine, but it’s anything but an untamed racer. Instead, the designers have taken the racebike’s design, filtered it through their years of two-stroke experience, and produced an amazingly civilized streetbike.

Of course, the RZV looks like the racer, from its beautifully made aluminum frame to its 50-degree V-Four twostroke powerplant. But important differences exist between last year’s race engine and the RZV engine. The RZV has reed valves instead of the racer’s disc valves; and both share a design that gears two separate crankshafts together in one crankcase, but only the street engine has a vibration-reducing balance shaft. And while the racer makes around l 50 bhp, the European version of the RZV makes 91, and the Japanese RZV we rode has restrictors in the exhaust system that drop bhp to 64.

Yamaha RZV500

$3381

Which is not to say that the Japanese RZV is slow; it runs high-12-second quarter-miles at 105 mph, with suprisingly good power over the entire rpm range. It pulls strongly from the bottom on up, with the best power coming between 6000 and 8500 rpm. In Tokyo traffic, the RZV could easily be ridden two gears higher than the accompanying four-stroke 400s, so torquey is its engine.

That’s one reason why the RZV seems at home on the street. It cruises the highway smoothly and comfortably. The fairing offers good protection and the seating position is not extreme. The engine has the same refinement as the one in the RZ350, with little but the exhaust note and the lack of engine braking to tell you it’s a two-stroke. The only intrusion is the engine vibration that buzzes the pegs and grips above 8000 rpm, and at any speed on trailing throttle.

On the racetrack, the RZV lives up to its heritage. The steering is rather heavy, but the bike can be rolled into corners quickly and securely. Only the tires are not trackworthy, allowing the bike to slide prematurely for such a high-performance motorcycle.

But it’s no surprise that the RZV does well on the racetrack. The surprise is that a street-going GP replica can have sufficient manners to work as a civilized sport-tourer.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cycle World Editorial

Cycle World EditorialOf Myths And Mystiques

November 1984 By Paul Dean -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

November 1984 -

Cycle World Roundup

Cycle World RoundupThe 15 Million Dollar Motorcycle

November 1984 By David Edwards -

Special Section

Special SectionBeyond Pit Road

November 1984 By Ken Vreeke -

Special Section

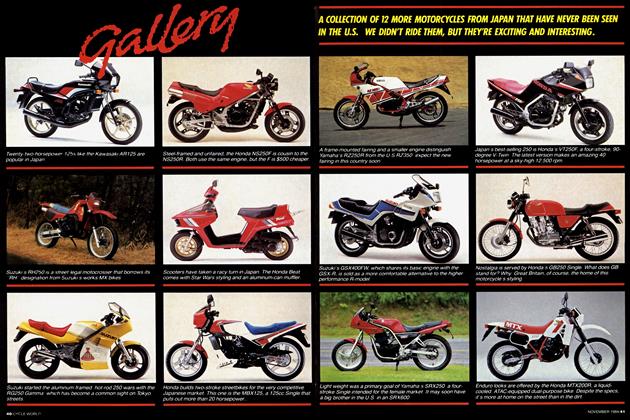

Special SectionGallery

November 1984 -

Special Section

Special SectionThe Tokyo Grand Prix

November 1984