Beyond Pit Road

HONDA RACING CORPORATION

Ken Vreeke

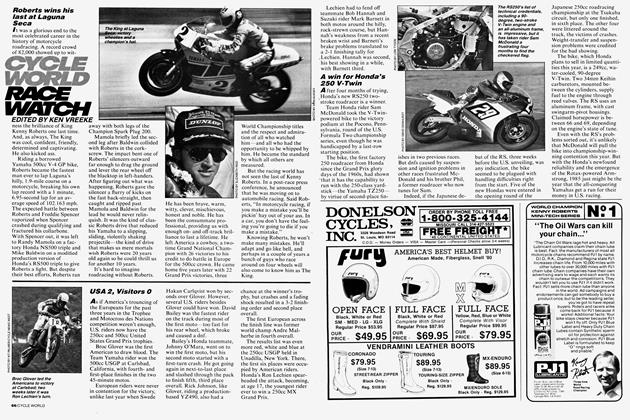

Standing in the lobby of HRC, we are surrounded by the ornamentation of battle: silver victory cups, gold world-championship medallions, photographs of Freddie Spencer, Mike Baldwin, Eddie Lejeune, David Bailey and the rest of Honda’s hired guns. In the center of the white-tiled vestibule is an enormous scoreboard, labeled “’84 Race Guide,” that keeps track of more than 20 separate world and national championships, with blood-red squares woven like bull’seyes into a white background. Each bull’s-eye denotes a win at a championship event, and at this stage there are 95 bull’s-eyes in all. This scoreboard is what HRC is all about.

At the beginning of the 1982 racing season, Honda issued a manifesto outlining its forthcoming racing plans. In essence, that declaration stated quite clearly that Honda would compete in all facets of motorcycle sport, and that the company intended to pursue this venture with unprecedented brio.

Integral to Honda’s master plan was the formation of HRC (Honda Racing Corporation) to replace the existing RSC (Racing Service Center) organization. At the time, the development of all Honda motorcycle products, including racing machines, was carried out by Honda R&D, a separate company within the parent Honda organization. All racing equipment was deployed, however, through RSC, yet another sibling company, headquartered at the Honda-owned Suzuka Circuit testing facility. Honda R&D already was heavily involved in racing, and there was little room for expansion within the bulging walls of its facility; so plans were made to phase out RSC entirely and build a separate new R&D center that could be devoted solely to competition. That would streamline the development of racing machinery and allow the company to focus its energies more sharply on the business of winning championships.

By September of 1982, HRC had been formed; and seven months later, the new racing R&D center, with a work force of 240, officially opened its doors in Niiza City, 20 miles northwest of Tokyo. Thus far, little is known and much has been speculated about the new operation because its doors open only to HRC employees and blood relatives of Soichiro Honda. For all others, entry is available when pigs learn to fly. Secrecy is, after all, a key element in mounting a successful frontal assault.

So how, then, did two representatives of the press,Technical Editor Steve Anderson and I, come to find ourselves in the belly of the beast? Good question. One for which, at that point, we had no answer. We had requested a visit to see what we could see and to hold counsel with the nimble minds behind Honda’s front-line weaponry—fully expecting, of course, to be politely turned down. Much to our surprise, Honda agreed and threw in a guided tour to boot, so long as we left our cameras in the lobby—directly below a flock of hovering pigs.

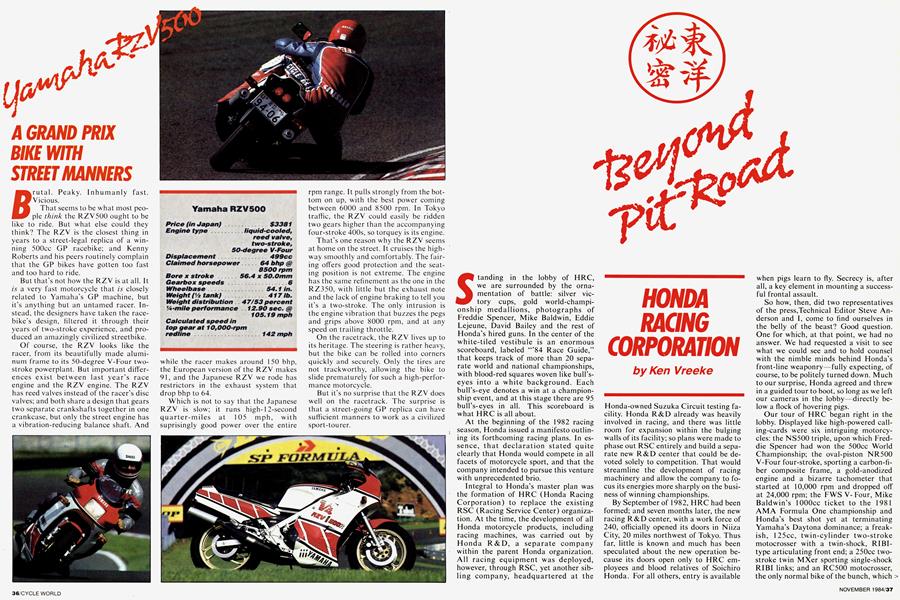

Our tour of HRC began right in the lobby. Displayed like high-powered calling-cards were six intriguing motorcycles: the NS500 triple, upon which Freddie Spencer had won the 500cc World Championship; the oval-piston NR500 V-Four four-stroke, sporting a carbon-fiber composite frame, a gold-anodized engine and a bizarre tachometer that started at 10,000 rpm and dropped off at 24,000 rpm; the FWS V-Four, Mike Baldwin’s lOOOcc ticket to the 1981 AMA Formula One championship and Honda’s best shot yet at terminating Yamaha’s Daytona dominance; a freakish, 125cc, twin-cylinder two-stroke motocrosser with a twin-shock, RIBItype articulating front end; a 250cc twostroke twin MXer sporting single-shock RIBI links; and an RC500 motocrosser, the only normal bike of the bunch, which bore the Number One plate earned by Andre Malherbe in the ’81 500cc motocross world championships.

Led by tour guides Yoshio Yamada, PR man, Yukinobu Terada, director of number-crunching, and Takeo Fukui, design director in command of all of Honda’s grand prix racing efforts, we descended through antiseptic halls to the first floor where ideas are sculpted into working prototypes. We passed through a very complete machine shop, an immaculate inspection area, and into the dyno department, which houses seven Schenk engine dynos and two chassis dynos. The most interesting room contains the field analysis equipment, computers that transform data collected by various sensors attached to the racebikes into hard numbers and graphs. These sensors can monitor throttle position, ground speed, engine rpm, suspension stroke, axle acceleration, and even the slip-rate or wheelspin of the front and rear tires throughout the course of a lap. The slip-rate information has proven invaluable in the development of Honda’s dirt-trackers, where the balance of power and wheelspin is the whole ballgame.

Most of HRC’s technicians are young and fresh out of engineering schools in Japan. Natural selection hoists the most creative minds out of HRC’s workshop trenches and into the design groups, which are headed by 10 experienced engineers. The idea is for the older hands to have a conservative influence on the radical ideas of the company’s exuberant youth. There also is a constant roll-over of engineers at HRC, for each year, five percent of those eligible are moved to the prestigious design groups. They are the replacements for those who have graduated from racing to apply their racetrack technology to mass-produced machines.

Honda has used this system to nurture innovation ever since the company began racing decades ago. Shoichiro Irimajiri was a star pupil of the system, designing wonderfully bizarre machines that kept Honda at the forefront of GP roadracing throughout the Sixties. He went on to create the fabled CBX, and now heads Honda’s manufacturing plant in Ohio.

With few exceptions, it takes about five years for a budding designer to leave the workshop behind, but there are exceptions. Mr. Kanazawa, the man responsible for the oval-piston NR500, is one such exception. He designed the NR practically before the ink was dry on his diploma, and is generally viewed by HRC management as the Irimajiri of the Eighties. His latest brainchild is a turbocharged 250cc four-stroke, with which Honda hopes to outgun the two-strokes for the 500cc roadracing world championship. The target date for this bold venture is the ’86 season, when the FIM rules will permit the use of such machines; but realistically, the turbo NR250 probably won’t debut until the 1987 racing season.

As we strolled through the machine shop, we spotted shelf upon shelf of oval pistons, displacement unknown. Mr. Fukui would reveal only that the new engine did indeed use oval pistons, and that the configuration was a V-Twin, using a single crank, with at least eight valves per cylinder and the turbocharger located in the cleft of the vee. With the exhaust ports leading into the center of the vee, the turbo unit benefits from the highest possible concentration of exhaust energy. And with a minimum of turbo plumbing to deal with, HRC engineers have made significant progress in minimizing turbo lag. To further reduce lag, Honda has produced its own turbo unit that uses a lightweight ceramic turbine/ compressor assembly.

We also learned that Honda engineers have solved the sealing problems that bothered the Dykes-type rings used on the NR500's pistons. This has opened up vast areas of opportunity for the oval-piston engine, and Honda is wagering heavily on its potential for the future.

At this stage of development, however, HRC engineers are finding it difficult to extract enough power out of just 250cc to be competitive in GP racing. We suspect the horsepower target must be between 145 and 150 at the crankshaft. Dialing in more boost and raising the rpm ceiling has thus far resulted mostly in spectacular engine melt-downs. And when the engine does hold together, it gobbles fuel at such a furious rate that it couldn’t finish a GP with the current fuel restrictions.

HONDA IS DEAD-SERIOUS ABOUT FOUR-STROKES AND VIEWS THEM AS THE COMPANY'S ONE TRUE CALLING

When and if the current problems are solved, Honda will still be faced with the weight penalty of a four-stroke engine. The engineers claim that fairly standard materials—standard in this case being aluminum, titanium and magnesium will have to be used in this engine for the sake of durability, though experiments with ceramic valves have been underway for some time. Honda will no doubt try to offset the engine’s weight through the use of ultra-lightweight chassis materials, probably carbon-fiber, possibly in a monocoque design using a honeycomb structure. Honda also plans to petition the FIM to bump four-stroke turbo displacement limits up to 375cc.

The NR250 turbo four-stroke project is really only the tip of the iceberg. Mr. Fukui and Mr. Terada made it clear that Honda views itself as a four-stroke company that will not be satisfied until it wins all of its championships with fourstrokes. Of the seven engine dynos in use at HRC during our visit, the predominant sound piercing the insulated walls was that of poppet-valve engines. Engineers were hard at work on a 600cc fourstroke Single that eventually might be sold here in the U.S. for dirt-track use; and there were a number of dyno rooms that were dark but still warm from the recent running of . . . something.

That something could well have been a 500cc four-stroke motocross powerplant. That's right, fans, motocross. Honda plans to mount a serious assault on the 500cc MX world championship with a four-stroke, and will begin with race development in the Japanese Nationals next season, hopefully progressing to the GP circuit as early as 1986. If all goes well, Honda four-strokes might even find their way into the 125 and 250 classes. Specifics on these engines may depend on the success of the oval-piston NR250, but it's likely that Honda's first wave of four-stroke motocrossers will use conventional pistons.

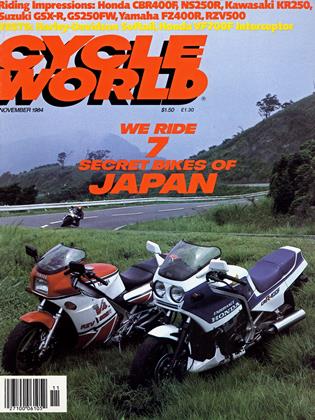

Realistically, the strategists at Honda know that the transition from two-stroke to four-stroke racing will not take place overnight. Which is why we might see HRC running two separate teams in the future, one on two-strokes and one using four-strokes. HRC has already made plans to field a 250cc grand prix roadracing effort next year with the NS250 two-stroke through its European importers.

All this boils down to one inescapable conclusion: Honda is dead-serious about four-strokes and views them as the company’s One True Calling.

For HRC, there are many questions to be answered, most of them hinging on the success of Mr. Kanazawa’s oval-piston engine. But for you and me, it is a question of how much of this racing technology will find its way into mass-production machines. While some motorcycle manufacturers race what they sell, Honda seems more likely to sell what it races. Witness the MVX250F twostroke Triple and the NS250 two-stroke Twin sold in Japan and Europe, as well as the V-Four Interceptor series. All of these motorcycles directly reflect technology learned at the racetrack.

Considering the incalculable millions Honda has funneled into racing, could oval-piston motorcycles for the masses be far off? Already the Japanese press is rife with rumors of Honda preparing for the introduction of a high-revving, turbocharged, 250cc V-Twin four-stroke for the Japanese market. And the fact that Honda allowed two American motojournalists to poke around inside HRC’s secret nerve center indicates that the company wants to start preparing the public for what’s to come.

We’ve seen a few of Honda’s new ideas. And in all likelihood, that is only the beginning.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cycle World Editorial

Cycle World EditorialOf Myths And Mystiques

November 1984 By Paul Dean -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

November 1984 -

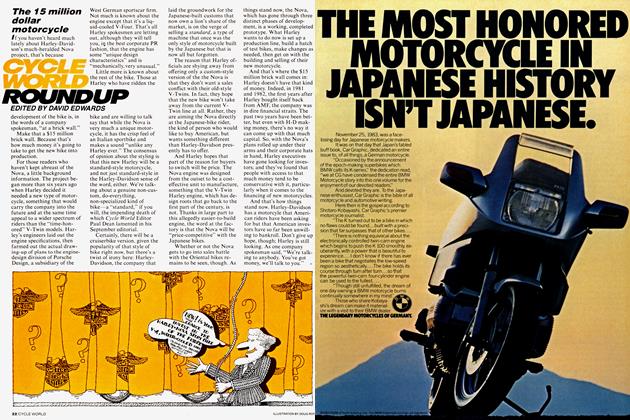

Cycle World Roundup

Cycle World RoundupThe 15 Million Dollar Motorcycle

November 1984 By David Edwards -

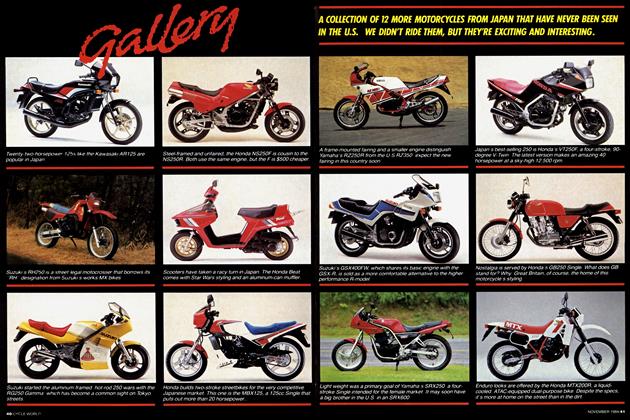

Special Section

Special SectionGallery

November 1984 -

Special Section

Special SectionThe Tokyo Grand Prix

November 1984 -

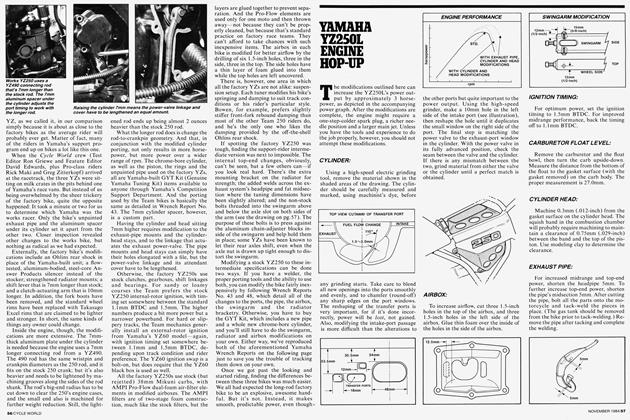

Yamaha Yz250l Engine Hop-Up

November 1984