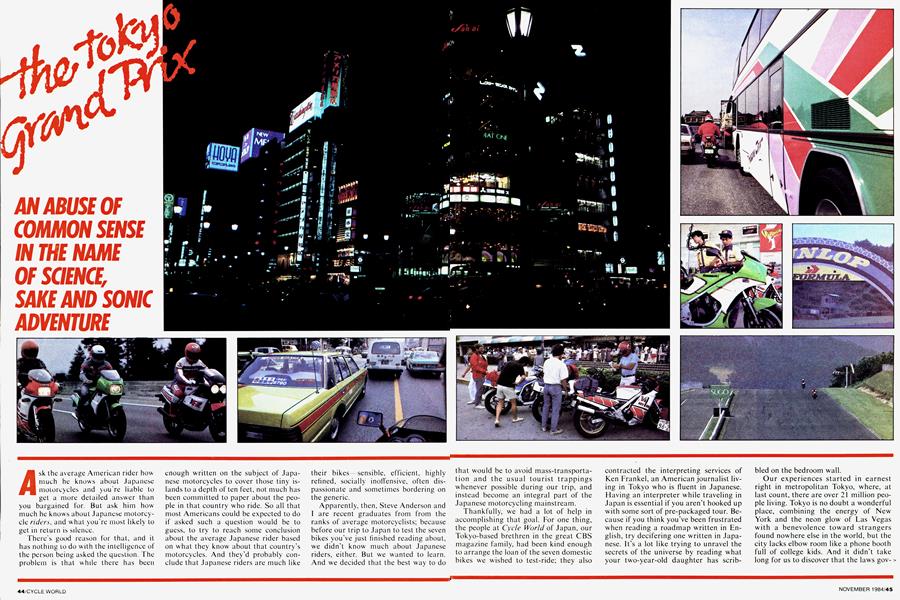

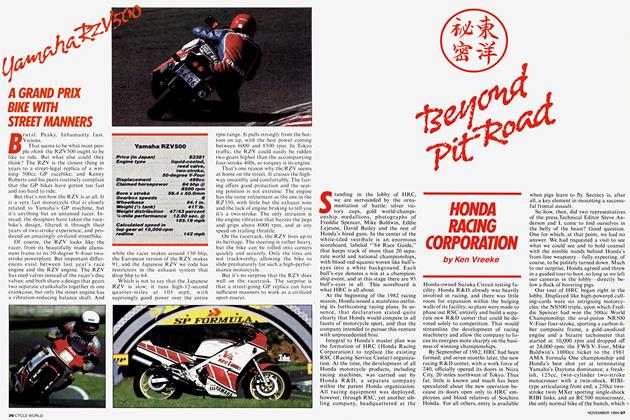

the Tokyo Grand Prix

AN ABUSE OF COMMON SENSE IN THE NAME OF SCIENCE, SAKE AND SONIC ADVENTURE

Ask the average American rider how much he knows about Japanese motorcycles and you're liable to get a more detailed answer than you bargained for. But ask him how much he knows about Japanese motorcycle riders, and what you’re most likely to get in return is silence.

There's good reason for that, and it has nothing to do with the intelligence of the person being asked the question. The problem is that while there has been enough written on the subject of Japanese motorcycles to cover those tiny islands to a depth of ten feet, not much has been committed to paper about the people in that country who ride. So all that most Americans could be expected to do if asked such a question would be to guess, to try to reach some conclusion about the average Japanese rider based on what they know about that country’s motorcycles. And they’d probably conclude that Japanese riders are much like their bikes sensible, efficient, highly refined, socially inoffensive, often dispassionate and sometimes bordering on the generic.

Apparently, then, Steve Anderson and I are recent graduates from from the ranks of average motorcyclists; because before our trip to Japan to test the seven bikes you’ve just finished reading about, we didn’t know much about Japanese riders, either. But we wanted to learn. And we decided that the best way to do that would be to avoid mass-transportation and the usual tourist trappings whenever possible during our trip, and instead become an integral part of the Japanese motorcycling mainstream.

Thankfully, we had a lot of help in accomplishing that goal. For one thing, the people at Cycle World of Japan, our Tokyo-based brethren in the great CBS magazine family, had been kind enough to arrange the loan of the seven domestic bikes we wished to test-ride; they also contracted the interpreting services of Ken Frankel, an American journalist living in Tokyo who is fluent in Japanese. Having an interpreter while traveling in Japan is essential if you aren’t hooked up with some sort of pre-packaged tour. Because if you think you’ve been frustrated when reading a roadmap written in English, try decifering one written in Japanese. It’s a lot like trying to unravel the secrets of the universe by reading what your two-year-old daughter has scribbled on the bedroom wall.

Our experiences started in earnest right in metropolitan Tokyo, where, at last count, there are over 21 million people living. Tokyo is no doubt a wonderful place, combining the energy of New York and the neon glow of Las Vegas with a benevolence toward strangers found nowhere else in the world, but the city lacks elbow room like a phone booth full of college kids. And it didn’t take long for us to discover that the laws governing Tokyo traffic either are extremely liberal or largely ignored by most everyone. Either way, it didn’t matter, since we couldn’t have read them anyway.

To Western eyes, Tokyo traffic looks downright deadly, appearing to be a chaotic tangle of near-misses that always seems on the verge of crashing to a halt in one giant, flaming pile-up. Cars change lanes, leap away from stoplights and grind to a halt at a pace that would make Richard Petty a little nervous. So intense is Tokyo traffic that one company has introduced a video game, called Zippy Rider, that pits a lone motorcycle against a field of swerving traffic. The game is one of those sweaty-palm affairs that capture all of the sporting aspects of Tokyo traffic, in spirit if not in actuality.

Despite its dark-star density, though, Tokyo traffic flows steadily onward. Accidents are rare occurrences, mopeds and motorcycles are plentiful, and fists are seldom raised in anger. But only in Japan could all of this possibly work. Install American drivers in Tokyo traffic and try to move it at the same pace and you’d cause more destruction than another world war.

The catch to all this is that you have to be damn good at the controls to survive. The level of driving and riding competence in Tokyo is uncommonly high, partially because of strict licensing laws and partially because of Japanese penal code 21 1. To a certain extent, this one article controls the whole ballgame. It labels any motor vehicle operator as a professional; and under Japanese liability, any licensed professional who causes damage or injury as a result of negligence is subject to criminal prosecution. Hit somebody or force someone off the road and you could find yourself in the slammer.

There is also a “Last Chance” liability law, which states that you must do everything in your power to avoid an accident regardless of fault. If you don’t, you might find yourself sharing a cell with the driver who rammed you. Worse still, serving jail time in Japan can get you and your entire family ostracized from the rest of society.

Despite its Big Brother overtones, this self-regulating, drive-at-your-own-risk system works. It awards driving skill and ingenuity, and practically guarantees that all women will put on their make-up before leaving home, that myopies and drunks will take a bus, train, subway or cab, and that motorcyclists have a fighting chance.

Lucky for us, we didn’t know about Japanese liability when we rode into the crucible. If we had, we probably would have been so paranoid that we’d have gotten in everybody’s way. As it was, we were a menace mostly to ourselves, bobbing and weaving through traffic and generally blundering across town in the wake of Ken Lrankel.

Actually, the first thing we learned about riding in Tokyo was to forget about trying to keep up with Lrankel. He is to Tokyo traffic what Lreddie Spencer is to GP racing. Lrankel owns 14 motorcycles and possess an ability to get through Tokyo traffic that has earned him folk-hero status with the locals. His Japanese friends refer to him simply as “Strange Loreigner,” if not because of his penchant for eating creepy-crawlies that even the natives won’t touch, then because of his frenzied Tokyo riding pace, and the fact that he once passed a speeding ambulance as it raced through downtown Tokyo.

Next, we discovered that lane-splitting is a way of life in Tokyo. Even the cars do it. Adequate space between door handles and kneecaps is measured in millimeters, so that by comparison, Southern California lane-splitting is a yawn. Only woodsriding through tightly spaced trees even comes close.

..WE DISCOVERED THAT LANE-SPLITTING IS A WAY OF LIFE IN TOKYO. EVEN THE CARS DO IT."

On top of that, traffic signals are virtually impossible to spot against a background comprised of scores of brightly colored signs. Slots in traffic are where you make them, lanes are where you find them. As a result, Steve Anderson, a man who can keep a running balance of two checkbooks in his head while doing other calculations, like computing the specific density of Mars, suffered nearterminal sensory overload while blitzing through Tokyo traffic. At day’s end, he’d simply collapse in an exhausted heap.

Then there is Tokyo’s triple-threat to contend with; cabbies, truck drivers and fast-food delivery boys on mopeds. These people are working, and in the spirit of the great Japanese work ethic, they go at it with a vengence. Cab drivers and truck drivers don’t give an inch. And beware of moped riders bearing noodles, for these delivery boys, with precarious-looking contraptions for carrying trays of hot lunches cantilevered above the rear wheels, will take you out before letting said lunches get cold. In the trail of flying Lrankel, we got the hang of riding on the wrong side of the road, passing on the right between oncoming traffic, riding in the middle with about an inch to spare on each side of the handlebars, and riding on the left between traffic and assorted obstacles such as curbs, parked cars, vending machines, storefronts and pedestrians.

Such behavior would have gotten us shot on sight anywhere else, but in Tokyo nobody even seemed upset by it. Most, in fact, didn’t even appear to notice. And that, as much as anything else, is what stuck in our minds about riding in Japan—that the same tactics that would earn you a season pass into the local lockup on this side of the Pacific seemed almost to be a way of life on that side. Where else can you ride within a foot of pedestrians and not even get a rise out of them? Or dive between a car and a curb in the middle of a turn and be applauded by the driver for executing the maneuver so nicely? Or nearly get squashed between a truckload of pigs and a careening taxi full of Albanian diplomats while being passed by a 16-year-old girl riding a 10,000-rpm moped?

Indeed, one spirited ride through Tokyo on two wheels can net enough war stories to last an entire winter. And the city is a motorcyclist’s nirvana from a hardware standpoint, as well, for there are hordes of bikes on the streets day and night. The machinery runs from the mundane (by Japanese standards), such as Honda VL250s, Suzuki RG250 Gammas, Yamaha RZs and Kawasaki KR250s, to the exotic, as in Ducatis, BMWs, Harley-Davidsons and even the occasional Bimota. And Tokyo riders not only possess the very slickest of motorcycles and exceptional riding skills, they have wardrobes to match, ranging from full leathers for sportbike riders to complete motocross attire for dual-purpose pilots. Best of all, if a rider strolls into a restaurant wearing his Lreddie Spencerreplica leathers, nobody sneers at him, for a motorcycle-riding costume is no more out of place in public than a kimono or a jogging suit.

There is one group of riders, however, that fulfills the role of society’s rejects. They’re called the Boku-Zoku, or explosive riders, and that pretty much describes what they look like tearing away from a Tokyo stoplight in a pack of 30 at three a.m. They ride in large gangs, only come out at night and somehow manage to elude capture by the authorities. They don’t rape or pillage or any of that, but they do ride around on big, powerful inline-Lours equipped with open megaphones and air-horns, honking wildly, revving their engines, running stoplights and generally being a public nuisance. Little is known about these hellions except that they all wear sandals—ladies’ sandals, no less—when they ride. Nobody quite knows why.

After three days of dealing with Tokyo traffic, and one sleepless night courtesy of the Boku-Zoku, Anderson, Frankel and I saddled up a trio of our test bikes— the Yamaha RZV500 and FZ400R, and the Kawasaki KR250—and headed for Sugoland, a racing complex about five hours to the north. We rented a truck (with driver) to transport the other four. In the claustrophobic, densely populated confines of Tokyo, we had learned little of our seven bikes’ performance potential, so we had to go someplace where the throttles could be held wide-open for a while, someplace where the sides of the tires could get a bit of scuffing.

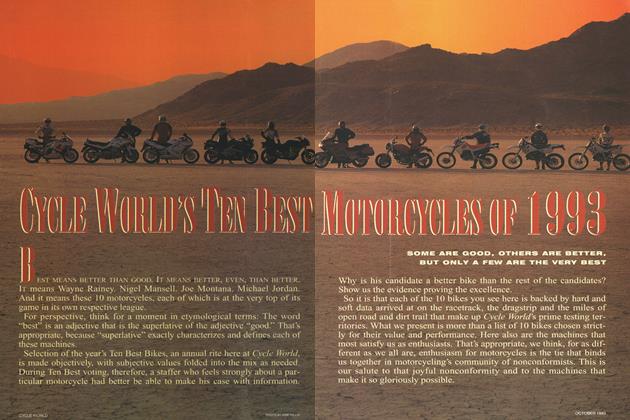

Neither Anderson nor I had ever heard of Sugoland, so we expected it to be a nice little racetrack nestled in the woods, a primitive facility lacking all the usual creature comforts such as food, shelter and indoor plumbing. Instead, we came upon The Most Wonderful Place In The World. Despite being surrounded by very little other than miles of forest, Sugoland has creature comforts that include an 18-hole golf course, a driving range, tennis courts, an archery range, swimming pools, hiking trails, three restaurants, an extravagant hotel, two gokart tracks, a motocross track, a trials course and an absolutely magnificent roadracing course complete with its own separate shelter and indoor plumbing.

Sugoland is owned by Yamaha, but the facility is open to the public and to any brand of motorcycle. On the weekends the place is packed with club roadracers, who line up for miles to get a crack at this fabulous racetrack. There’s even a rider-training school at Sugo for aspiring Tokyo motorcycle policemen, all of whom ride white Honda 650 Nighthawk police bikes. We had a chance to watch them go through the part of their training program in which they rode real trials bikes on a nasty little trials course and piloted their Nighthawks on the roadracing course. These future moto-cops were good, even in the training stage, and in all likelihood might even have been able to keep up with Frankel in Tokyo traffic.

The level of riding skill achieved by those students isn't that far above average, however, because the tests that a Japanese rider must pass to be issued a motorcycle license are anything but a piece of cake. There are three separate licensing levels based on the size of motorcycle you wish to ride: 0-50cc, 50400cc, and 400cc and over. The 400ccand-over licensing test in particular is so tough that failing as many as a dozen times for minor infractions is not at all uncommon. And once you fail, you must wait at least two months before you can take the test again. It’s not unusual for a rider to end up paying as much as $600 in exam fees before he gets a license to ride bikes bigger than 400cc. But once he succeeds, he joins Japan’s motorcycling elite by becoming one of the few (two percent) qualified to ride the “big” bikes.

That helps explain why our RZV500 created so much excitement wherever we rode it. One rider in particular, who was dressed in full leathers and riding Suzuki’s 400cc GSX-R, handed us his camera and asked that we take a picture of him astride the RZV. He had never seen one in the flesh and figured he probably wouldn’t see another for some time, and he wanted to capture the moment for his scrapbook.

But if you think that’s ironic, consider the riders who sidestep Japan’s laws restricting domestic motorcycle sales to bikes displacing 750cc or less. They have to pay a considerable premium to have Japanese-built export models of more than 750cc brought back into the country as “imported” motorcycles; and they spend a small fortune to bring large-displacement, foreign bikes (BMW, Harley-Davidson, etc.) into the country.

" .1TOKYO TRAFFIC SEEMS ON THE VERGE OF CRASHING TO A HALT IN ONE GIANT, FLAMING PILE-UP."

This displacement restriction, as well as the tri-level licensing structure, is designed to keep young bucks from wadding themsleves up into little balls by making it difficult for them to get their hands on machines too big for them to handle. Like Japan’s mandatory helmet law, it’s a case of necessity being the mother of intervention.

In addition, it is illegal in Japan to ride two-up on main roads. The problem, according to Ken Frankel, is that there are only two kinds of riders in Japan, the conservatives and the banzais; and the technique for being a proper banzai passenger is to flail your arms, kick your feet and hop up-and-down on the seat while the rider is going as fast as he can. The Japanese government grew weary of scraping “proper” banzai passengers off the road and simply made it illegal to carry passengers on main highways.

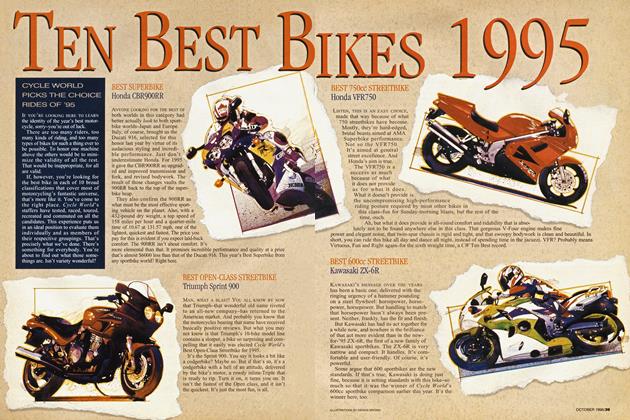

It’s easy to understand, though, how any motorcyclist in Tokyo—rider or passenger—can get more than a little antsy for some sport-riding action. So it was, just a few days after our return to Tokyo from Sugo, that we yearned to get out of the city and scuff a few footpegs. Our Japanese hosts from Cycle World suggested a ride on the snaking mountain roads in Hakone, a famous resort area in the foothills of Mt. Fuji. And by all observations, Hakone is the place to go if you’re a devoted sportbike rider with a need to escape the congestion of Tokyo. We came upon hundreds of would-be knee-draggers swarming the canyons on everything from Honda’s British-bikereplica Clubmans to authentic Britbikes, from decidedly un-sporty machines like Harleys to hardcore sportbikes like Kawasaki Ninjas. Just about everyone rode rather conservatively, mostly because of heavy traffic but partly because the roads in Hakone cling to sheer cliffs, meaning that a miscalculation can put a rider into the canyon. But every once in a while a certifiable crazy would fly past at full song, footpeg and duct-taped knee defiantly grazing the asphalt.

We hadn’t ridden on an unclogged stretch of asphalt since leaving Sugoland days earlier, however, so we were in need of at least one full-on, twisty-road encounter before heading back into the miasma of Tokyo. We left Hakone in late afternoon and motored to Kagosaka Pass, Frankel’s favorite road, but it was jammed with slow-moving Sunday drivers. Frankel knew of another road nearby, a secret road. It was just what we were looking for—a sinuous little onelane roller-coaster ride that twirled through dark forests and over suspended bridges. Traffic was unusually light and we took full advantage, giving the bikes their best workout since Sugo.

That little stretch of unoccupied asphalt took on greater significance as the cluttered streets of Tokyo closed in around us. In the U.S., we tend to take wide-open spaces for granted, and we forget that we can run belly-to-theground on big Superbikes just about any time we feel the urge. But Japanese riders can’t even buy those machines, and even if they could, they’d have no place to ride them.

Once you understand that Japan is roughly the size of California but has a population approximately equal to that of the entire U.S., you begin to appreciate why the Japanese ride the kinds of bikes they do in the way that they do. There are precious few wide-open spaces and even fewer uncrowded roads. But this doesn’t seem to dampen the spirits of Japanese riders. Their commitment to and enthusiasm for motorcycling is reinforced every time the opportunity arises, be it a few scant miles of relatively uncluttered highway or that rare deserted road—or even that tiniest of gaps in hectic downtown traffic.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cycle World Editorial

Cycle World EditorialOf Myths And Mystiques

November 1984 By Paul Dean -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

November 1984 -

Cycle World Roundup

Cycle World RoundupThe 15 Million Dollar Motorcycle

November 1984 By David Edwards -

Special Section

Special SectionBeyond Pit Road

November 1984 By Ken Vreeke -

Special Section

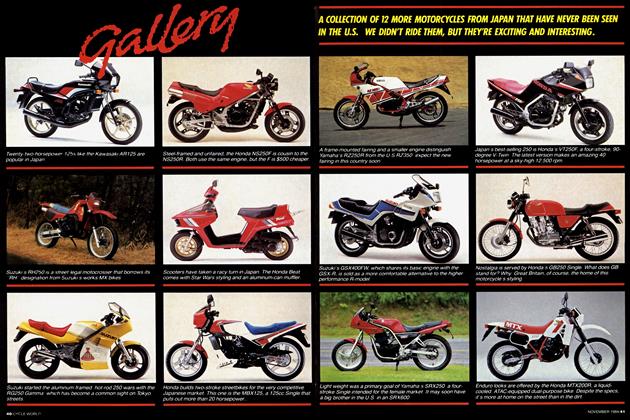

Special SectionGallery

November 1984 -

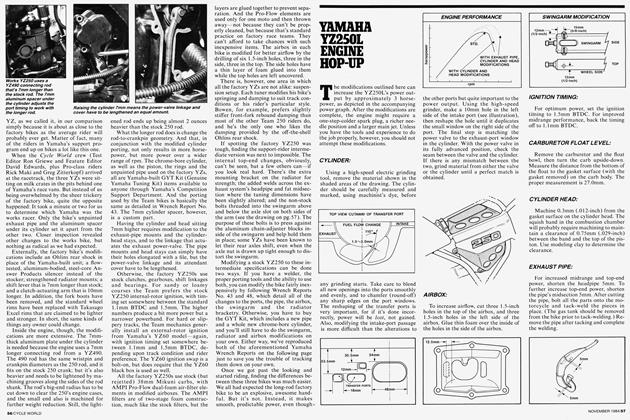

Yamaha Yz250l Engine Hop-Up

November 1984