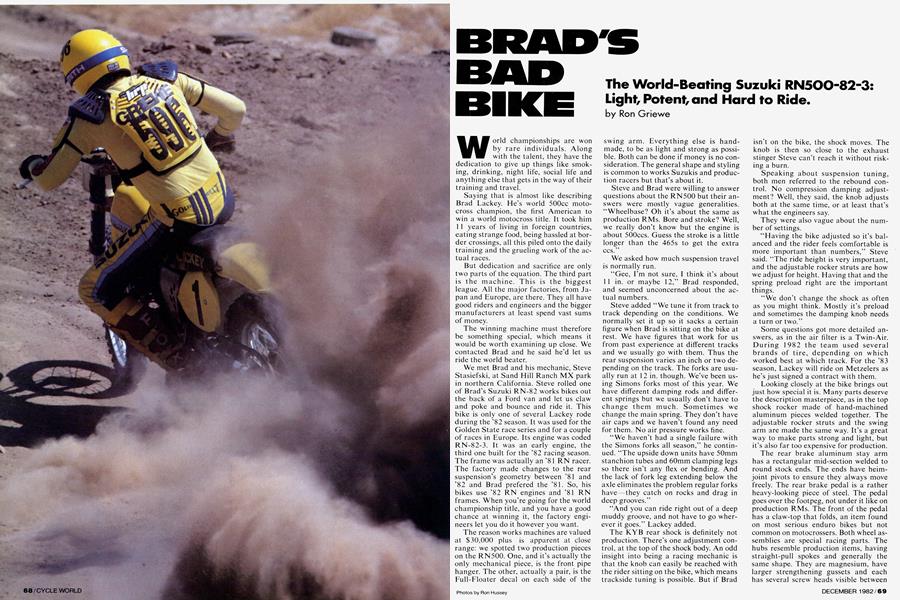

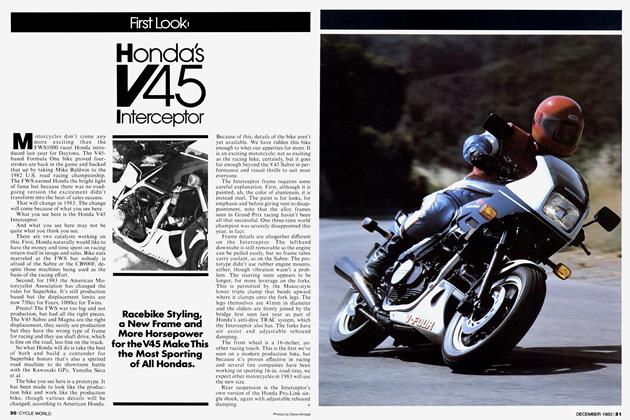

BRAD'S BAD BIKE

The World-Beating Suzuki RN500-82-3: Light, Potent, and Hard to Ride.

Ron Griewe

World championships are won by rare individuals. Along with the talent, they have the dedication to give up things like smoking, drinking, night life, social life and anything else that gets in the way of their training and travel.

Saying that is almost like describing Brad Lackey. He’s world 500cc motocross champion, the first American to win a world motocross title. It took him 11 years of living in foreign countries, eating strange food, being hassled at border crossings, all this piled onto the daily training and the grueling work of the actual races.

But dedication and sacrifice are only two parts of the equation. The third part is the machine. This is the biggest league. All the major factories, from Japan and Europe, are there. They all have good riders and engineers and the bigger manufacturers at least spend vast sums of money.

The winning machine must therefore be something special, which means it would be worth examining up close. We contacted Brad and he said he’d let us ride the world beater.

We met Brad and his mechanic, Steve Stasiefski, at Sand Hill Ranch MX park in northern California. Steve rolled one of Brad’s Suzuki RN-82 works bikes out the back of a Ford van and let us claw and poke and bounce and ride it. This bike is only one of several Lackey rode during the ’82 season. It was used for the Golden State race series and for a couple of races in Europe. Its engine was coded RN-82-3. It was an early engine, the third one built for the ’82 racing season. The frame was actually an ’81 RN racer. The factory made changes to the rear suspension's geometry between ’81 and '82 and Brad prefered the ’81. So, his bikes use ’82 RN engines and ’81 RN frames. When you’re going for the world championship title, and you have a good chance at winning it, the factory engineers let you do it however you want.

The reason works machines are valued at $30,000 plus is apparent at close range: we spotted two production pieces on the RN500. One, and it’s actually the only mechanical piece, is the front pipe hanger. The other, actually a pair, is the Full-Floater decal on each side of the swing arm. Everything else is handmade, to be as light and strong as possible. Both can be done if money is no consideration. The general shape and styling is common to works Suzukis and production racers but that’s about it.

Steve and Brad were willing to answer questions about the RN500 but their answers were mostly vague generalities. “Wheelbase? Oh it’s about the same as production RMs. Bore and stroke? Well, we really don’t know but the engine is about 500ccs. Guess the stroke is a little longer than the 465s to get the extra CCS.”

We asked how much suspension travel is normally run.

“Gee, I’m not sure, I think it’s about 11 in. or maybe 12,” Brad responded, and seemed unconcerned about the actual numbers.

Steve added “We tune it from track to track depending on the conditions. We normally set it up so it sacks a certain figure when Brad is sitting on the bike at rest. We have figures that work for us from past experience at different tracks and we usually go with them. Thus the rear suspension varies an inch or two depending on the track. The forks are usually run at 12 in. though. We've been using Simons forks most of this year. We have different damping rods and different springs but we usually don’t have to change them much. Sometimes we change the main spring. They don’t have air caps and we haven’t found any need for them. No air pressure works fine.

“We haven’t had a single failure with the Simons forks all season,” he continued. “The upside down units have 50mm stanchion tubes and 60mm clamping legs so there isn’t any flex or bending. And the lack of fork leg extending below the axle eliminates the problem regular forks have—they catch on rocks and drag in deep grooves.”

“And you can ride right out of a deep muddy groove, and not have to go wherever it goes.” Lackey added.

The KYB rear shock is definitely not production. There’s one adjustment control, at the top of the shock body. An odd insight into being a racing mechanic is that the knob can easily be reached with the rider sitting on the bike, which means trackside tuning is possible. But if Brad isn't on the bike, the shock moves. The knob is then so close to the exhaust stinger Steve can’t reach it without risking a burn.

Speaking about suspension tuning, both men referred to the rebound control. No compression damping adjustment? Well, they said, the knob adjusts both at the same time, or at least that’s what the engineers say.

They were also vague about the number of settings.

“Having the bike adjusted so it’s balanced and the rider feels comfortable is more important than numbers,” Steve said. “The ride height is very important, and the adjustable rocker struts are how we adjust for height. Having that and the spring preload right are the important things.

“We don’t change the shock as often as you might think. Mostly it’s preload and sometimes the damping knob needs a turn or two.”

Some questions got more detailed answers, as in the air filter is a Twin-Air. During 1982 the team used several brands of tire, depending on which worked best at which track. For the ’83 season, Lackey will ride on Metzelers as he’s just signed a contract with them.

Looking closely at the bike brings out just how special it is. Many parts deserve the description masterpiece, as in the top shock rocker made of hand-machined aluminum pieces welded together. The adjustable rocker struts and the swing arm are made the same way. It's a great way to make parts strong and light, but it’s also far too expensive for production.

The rear brake aluminum stay arm has a rectangular mid-section welded to round stock ends. The ends have heimjoint pivots to ensure they always move freely. The rear brake pedal is a rather heavy-looking piece of steel. The pedal goes over the footpeg, not under it like on production RMs. The front of the pedal has a claw-top that folds, an item found on most serious enduro bikes but not common on motocrossers. Both wheel assemblies are special racing parts. The hubs resemble production items, having straight-pull spokes and generally the same shape. They are magnesium, have larger strengthening gussets and each has several screw heads visible between the gussets. The screws hold the steel brake liners in place. Spokes are fairly small in diameter, like spokes on production bikes; the straight-pull design means they don't have to be large to do the job. The front brake is a double-leading shoe, the rear a single-leading shoe.

Outwardly the RN’s chrome-moly steel frame doesn’t look much different from an RM frame . . . but, there is something, something that takes a while to notice . . . the frame isn’t the same on each side! The left side of the frame has two center tubes leaving the swing arm pivot to form a nice triangle, the right side only has one. The area inside the triangle on the left side is filled with a large airbox that contains one large filter. Trying to use the same extra frame tube on the right side of the bike would prohibit the use of the kick starter. Leaving it off also makes for better carburetor access. Getting to it from the left side is impossible but the right side is spacious. The rest of the frame’s tubes and general geometry don’t appear much different than those on production RMs.

The RN’s tiny cases look too small to hold the four-speed gearbox and crank. The cases are shrunk around the crank so closely that the crankcase isn’t any larger in diameter than the mag cover. The cylinder and head actually look much like those on production Yamaha 250YZ. The finning is massive at the top and tapers quickly to almost nothing at the bottom. These parts also appear to be magnesium but no one was sure or actually cared! An intake reed is standard and appears about the same size as production RMs. The 38mm Mikuni carb has a fiat slide and an aluminum body. The factory has magnesium-bodied carbs available to factory racers but Steve and Brad preferred the aluminumbodied model, claiming it gives better performance for some unexplainable reason. The shift lever has a steel tip that folds and Steve has tapped the end and installed a bolt to extend its length. The engine is low in the frame. The swing arm pivot to countershaft distance is minimal and the center lines of the swing arm pivot, countershaft sprocket and rear axle are exactly in line when the rider is aboard. This alignment and the close relationship of the swing arm pivot and countershaft sprocket means chain tension changes less when the rear wheel moves up and down. Production RMs don't use head stays between the engine head and frame, neither does the RN.

Many parts on the RN are things most of us are used to seeing on serious race bikes; the pipe is hand made from many small pieces carefully welded together, the silencer is aluminum, some of the bolts have drilled centers and everything is as simple and straightforward as possible. Brad’s RN, like other factory bikes we’ve inspected, has the controls moved, adjusted or modified so the rider is comfortable and doesn’t have to adapt. The RN’s tiny footpegs are rear-set about an inch, the specially built Ceet seat has the dip in it eliminated so it’s easier to move around on the bike, the shift lever end has been made longer so Brad doesn't miss it, the bars have a higher rise than normal (due to the thicker seat), the clutch lever is a straight blade lever, the front brake lever is a two-finger dogleg Magura, the throttle is a Gunnar Gasser, the grips are Tacki Grips, the rear fender is a normal RN fender and the front is a Preston Petty.

Straddling the RN500-82 proves the seat is as high as it looks. The built-up center and hard foam density place the rider above the bike. Starting the RN is normal as long as you remember this is a works bike with a BIG engine and high compression. Kick hard or the lever stops part way down. Once running the almost total lack of vibration is apparent. Even the best production 500 motocrossers don't run this smoothly.

There’s a hint of intimidation as we prepare to ride the RN. The crowd here consists of the world champion motocrosser and his mechanic; breaking the bike or being obviously slow doesn’t bear thinking about.

Oh hell, there aren’t three riders in the world who are capable of impressing Brad Lackey. Better to forget that and just ride as fast as is comfortable.

The four-speed transmission drops cleanly into low gear with no crunching or lurching. The clutch pulls smoothly and easily and releases without any grabbiness or abruptness. Low gear is much lower than low on an ‘82 RM465Z, actually so low as to be almost useless.

“Just take off in second, shift to third as soon as you can and then leave it in third,” was Brad's advice. “The engine is tuned for torque and lap times are 5 seconds faster if the bike is torqued around the track. Feels slower but the stop watch proves it isn’t so.”

“We use the same pipe, cylinder and carb as Alan King. If you listened at the last GP at Carlsbad you heard the difference,” Steve beamed.

“Tuning the carb can make the engine characteristics completely different. I put in a couple sizes larger needle jet, maybe three sizes larger pilot jet, and go two or three sizes smaller on the main jet. These changes move the bike’s power from the top and mid-range to the bottom and mid-range. It works on almost any bike and any carburetor.”

Brad’s RN does have torque. The engine makes serious power at an amazingly low speed, so much and so low in the rev band that you can effectively forget about turning the throttle wide open. This is a world class bike for world class riders and they’re the only ones who can handle this much power. Our pro rider thought maybe, with time and a fast course, he could get off the needle and onto the main jet. Our desert expert, who raced production open machines for years, figured he’d never know firsthand how much power the RN500 cranks out.

The engine’s sheer power is accented by the bike’s light weight, estimated at 225 lb. The lack of bulk helps the handling; a good rider can put the bike anyplace he wants. At the same time, the power to weight ratio puts even more demands on the rider. Sand Hills Park is hard and slippery. The RM would be even more thrilling, and demanding, on a loamy track where the rear wheel could get some traction.

Further, Brad’s RN is set up for Brad. As mentioned, because the factory wants to win they allow the top riders their choice of parts, their systems of tuning and to arrange things to suit their own styles.

Steve has mounted Brad’s pegs toward the rear, which is how Lackey likes them. And he’s 20 lb. lighter than either of our men.

There we were, on what felt like a light 250 with 750 power, sitting on what seemed like the rear fender. Rider weight and rider position and the incredible power meant it was very easy to get the front wheel too high.

The bike’s suspension wasn’t set up for Sand Hill’s slippery whoops and the rear bounced around quite a bit until the damping on the shock was adjusted a couple of clicks stiffen Then the rear wheel followed the track like magic. The rider was in complete control through corners on the RN. The exceptionally light weight, solid chassis and forks, let the rider go where he wants. Go high, low or use the berm. The bike never fights the rider or tries to stand up or fall down through any kind of corner.

The RN’s brakes are as serious as the engine. The front brake only takes one finger to quickly slow the bike. The rear is fine, with no lock-up or chatter, just predictable and quick stopping. All controls on the bike work extremely smoothly, so smooth they almost go unnoticed. The gearbox is so smooth the rider isn’t sure the bike has shifted. But he doesn’t need to shift often anyway. Brad was right—third gear is fine for the Sand Hill course. Even tight turns can be torqued through in third. Our faster test rider got into fourth briefly on the back straight, our slower guy never needed fourth. (Brad says he winds fourth in the back straight!)

Big jumps were of little concern. Landings are extremely smooth and completely jar-free. The bike lands as if the track was made of foam rubber; no jar, no bump, no suspension bottoming or weird rebounds.

If Suzuki’s RN500 sounds like the perfect open motocrosser, that’s because it is. Its light weight and incredible power take quite a bit of getting used to for anyone but a top pro level rider, but then those are the riders the bike is designed for. B3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue