OVER THE BARS IN BAJA

What One Man Learned about the Baja 1000 . . After it Was Too Late.

Bob Atkinson

After the contingency line crowd disappears, the Baja racer finds himself deep in thought. He tries to remember all the dangerous sections of the course, but there are too many. Delays bring frustration. Changes in weather bring uncertainty. Finally it begins and before the racer realizes it, he’s alone. There’s no one in sight... he has no way to judge how he’s doing. If he stops, there’s no noise. Baja, in short, becomes a personal experience.

Because Baja gets personal, it’s time for a new kind of Baja race report, a first-hand piece by a first-time rider who didn’t realize what he was getting into until it was too late.

My Baja began with a phone call from desert ace and friend Ron Griewe. “We ought to enter the Baja 1000. We’d do good. You go like hell in the tight stuff. I can hold my own. We’re both good wrenches. Why not?”

1 thought about it for a second and committed myself; easy to do when the event in question is six months away.

A week passed. Good judgment got the best of me as it usually does when I’m left alone and I decided to back out. I never got the chance. Before I could pick up the phone, Jim Hansen, Ron’s self-appointed organizer and confidant, walked into my office. Before I could get a word in edge wise, I heard things like, “Baja racing is a snap. It’s all a matter of logistics, my specialty. I’ll handle everything. All you have to do is show up and ride. Just like the pros. It’ll be neat.” I dismissed my second thoughts and gave in.

THE FIRST OBSTACLE

True to his word, Jim set out to obtain all the necessary bits and pieces. He brought my application to join SCORE. I returned it with a check for $20. A week later he brought the entry blank. I returned that with a check for $100, the required deposit if one chooses to participate in the drawing for starting position. Just as my checking account began to recover, Jim delivered another bill. “I saved the best for last.” he said as he handed me a bill which included my share of preliminary expenses, my share of the remaining entry fee, etc. Kiss another $231 goodbye.

“Baja racing is a snap. It’s all a matter of logistics, my specialty. Ill handle everything. All you have to do is show up and ride.”

Money is one thing. But it was nothing compared to the realization that we didn’t have a suitable bike. Baja racing requires a bike that’s fast, reliable and equipped with an electrical system to power quartzhalogen lights. Ron has a fast bike, I have a reliable bike with quartz-halogen lights. Putting the parts together in time, though, was impossible.

At this point I decided to withdraw again. Before I could dial the number, Jim appeared in person (his timing is flawless) and presented what turned out to be a solution. He suggested we obtain a Suzuki PE250 to use for the race, and for product evaluations.

Jim’s choice was perfect. We’d just run a PE250 1000 miles in Baja at racing speeds and had had no problems. Suzuki management greeted the idea with enthusiasm. They were curious about the bike’s racing potential. They said they’d give us a new one in a crate as soon as their first shipment arrived from Japan.

OBSTACLE TWO

Getting a good bike is a great relief because once that’s handled, the racer can concentrate on preparation, logistics and that sort of thing. Our bike, however, had been built but not shipped from Japan. In other words, our preparation suffered some.

Four weeks before the race, our PE arrived. From that day on, time became precious. Normal forms of recreation ceased. I either worked or worked on getting parts for the bike. Same for Jim, Ron, and Len Vucci, CYCLE WORLD’S Technical Editor.

Our major problem was one that confronts every Baja entrant. Lights. Len tested the PE electrical system and recorded 6 volts, 15 watts. To say this isn't enough is to say Harleys are heavy. We wanted to run two quartz lights. (The secondary light is for safety in case the main light fails at speed.) Each light draws 55 watts and requires 12 volts.

Len is something of a genius. He took the PE’s two lighting coils and stripped them. Each was rewound with heavier gauge wire and varnished to prevent failure at high rpm. The result was an output of 14 volts. 70 watts for each coil. That’s more like it.

Ron built a headlight bracket for the primary light; a Cibie Super Oscar with an 8-in. lens. The bracket is rubber-mounted and holds the light in three places. Two of the mounts form a pivot. The third is quick release and is used to adjust for distance.

The top light was more trouble. We wanted it small. We also wanted to carry this light only at night so it had to be easy to install. We began to search. Nothing appealed to us. Either the pattern was wrong or the housing fragile. The solution was a compromise; a Marchai with a good pattern but a weak plastic case. We reinforced the case and luckily, it held up. (We have since made an aluminum housing for this light).

When the mounts were complete, Len built a wiring harness. Each light has its own lighting coil. No switches are used. When you want lights, you stop and plug them in. It only takes seconds and it eliminates the possibility of switch failure.

At this point Len took custody of the bike. Ron and I were afraid the CDI black box would fail. They rarely do, but we are cautious types. Len was afraid Ron and I would botch the ignition if we messed with it. He was right, of course.

His solution was two black boxes. A switch selected Box A, or transferred to Box B if Box A failed. “Just don’t flip the switch with the engine running,” he warned us.

(All the preparation and pursuit of parts and testing and such was done after work, by the way, and in some cases replaced normal pastimes. Like sleeping.)

Maybe I should explain why logistics are such a problem.

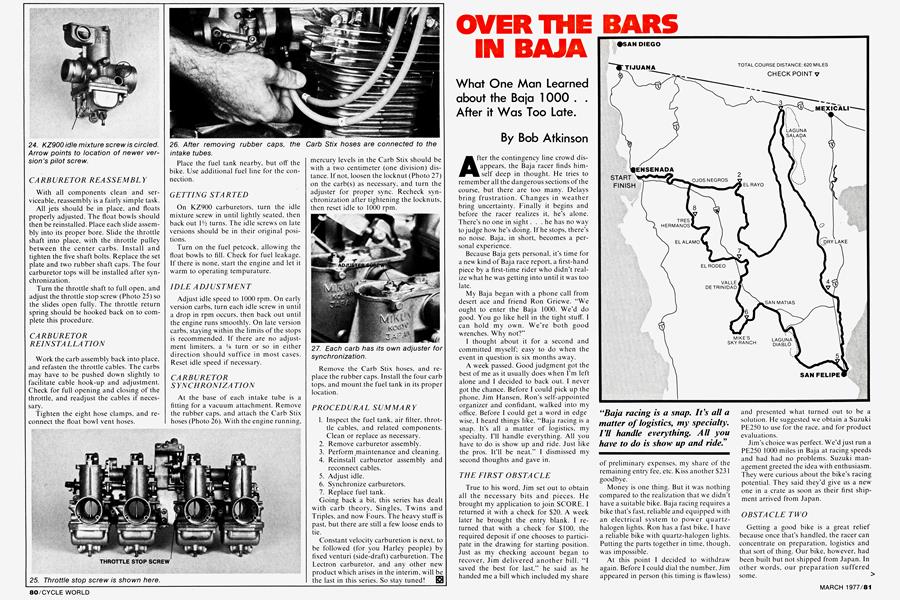

The course is a big circle, more or less. The start is in Ensenada, a town on the Pacific Ocean side of the peninsula. From there you blast over the mountains that ring Ensenada and head north, toward the border town of Mexicali. Just outside Mexicali, you turn around, parallel the north-bound course for awhile, then veer off toward San Felipe. San Felipe is as far south as the course gets. It’s also located on the Gulf side of the peninsula. From there you loop up through the mountains through San Mateos and Mike’s Sky Ranch; destination Valley de Trinidad. From Trinidad, you zig zag back and forth across Mexican Highway 6 en route back to Ensenada.

“It’s gonna be a piece of cake. You’ll love it Some of the prettiest country you’ll ever see.” I should have known I was going to be in deep trouble.

The actual route is sort of informal. The rules require you to check in at specified points. Some places you must follow the marked path, some places the route is free. The markings are good here, poor there and nonexistent someplace else. The burden for finding one’s way falls on the racer and his crew, so the actual race must be preceded by several weekends learning where to go.

Just learning the course isn’t enough. Look at it this way. A bike must be gassed up every 50 to 70 miles, depending on the terrain. Figure 60 as the average. Actual race distance is 620 miles (1000 now stands for kilometers). A minimum of seven stops, then, are required.

Because the course parallels Mexican Highway 6, you can get by with a single pit crew once you reach San Felipe. Prior to that, however, you need four, because the race course is more direct and faster than the combination paved/dirt roads pit crews must use.

PRE-RUN ONE

While Len was spending the weekend with the ignition rather than with his family, Ron and I and our pit crew spent the weekend conducting what I refer to as Prerun One.

On the way down all Jim could say was, “It’s gonna be a piece of cake. You’ll love it. Some of the prettiest country you’ll ever see.” I should have known I was going to be in deep trouble.

After a night on the floor of a Dodge van, we unloaded the bikes, suited up, and headed for Ojos Negros. Ron led, I followed. Jim took one of the trucks to Ojos Negros to gas us up. Jim Crow took a 4WD wagon across the mountains to gas us later.

I’ve been over the road from Ensenada to Ojos Negros several times. As always, it was fun, but dusty. Jim met us as planned and for the first time I had a good feeling about the race. Nothing like fun to inspire confidence.

Good times have a habit of disappearing just when you begin to enjoy them. On the straight fast grade out of town, my bike started acting up. It felt rich. No problem, I thought. I’ll just nurse it through the mountains. Rich is one thing, hardly running is another. By the time I crested the summit, I was faced with the task of wrenching on my scooter. Naturally, I didn’t have the right jets (my bike usually isn’t that fussy) so all I could do was drop the needle. No change.

Next stop, Nuevo Junction, which was to be my starting point in the race. We worked on my bike, Jim said something about how much I was going to like the next section, and we sped off. I liked the section for about 100 yards. That’s where the rocks began. One hundred miles later they stopped and were replaced with cross-grain that was worse.

Because of my engine and a flat tire we never reached San Felipe—our goal for the first day. Instead, we spent the night in the back of Jim Crow’s wagon.

In the middle of that sleepless night, it dawned on me that the trouble with my engine was ignition, not carburetion. Next morning 1 discovered closed points, made an adjustment, and off I went. The rest of my 230-mile section (Nuevo Junction to El Chinero) held no surprises. More crossgrain. More rocks. That’s it.

WORK AND PLEASURE COMBINED

The following week was spent preparing for CYCLE WORLD’S annual Baja trail ride. PE prep, as always, took place at night. ( Racing should be a requirement for every masochist.)

Because time was growing short, we spent one evening skillfully merging the Baja Trek course and the race course. This wasn't too difficult since both run right through Mike’s Sky Ranch. For Ron. this plan worked beautifully. He helped us on the Trek and got to finish pre-running the course. I, on the other hand, spent yet another night in the desert, this time nursing in an open cockpit sweep vehicle in the rain.

Back to work. Back to modifying the PE. K&N filters, Works Performance Shocks, dual control cables everywhere, a 3.50-21 front tire, safety-wire, tools in a Malcolm Smith bag, etc. completed the project.

MORE GOOD NEWS

Just as things were looking up, SCORE issued its first of several blows. They changed the route. Car drivers, it seems, had complained about the roughness of the course between Checkpoint Three (near Mexicali) and Checkpoint Four (El Chinero, which is close to San Felipe). They decided in favor of open running which meant you could hop on Laguna Salada dry lake (weather permitting) and run wide open. Wide open for us is 75 mph. On the original course we were lucky to average 35 mph. Laguna Salada was in my section of the course. Since I did not know the best way down the lake, I was faced with yet another pre-run.

I was not overjoyed. First of all. it costs a lot of money to pre-run. You can wear out a motorcycle, in this case, my own. You can also spend an incredible amount of money on gas. Each pre-run required running two vans from Los Angeles to Mexico. One of the vans has to continue on to provide partial pit support. Then there’s the four-wheel drive required in my section. Divide this by two racers and you come up with $100 each ... if your pit support doesn’t hit you up too hard. Change not overjoyed to really upset.

Realizing SCORE could make other changes, we put off our final pre-run until two days before the race. For me, that stretched a two day vacation to four.

At this point, Jim decided that 1 should not be allowed to ride a motorcycle before the race. “Too dangerous,’’ he said. So we made the final pre-run in a four-wheel drive. Jim Crow, my pit support for the altered section of the course, also accompanied us. It isn’t even easy to pit for someone in Baja.

As it turned out, Laguna Salada is 61 miles long. Staying on the lake bed cuts 20 miles off the length of the original course. We chose to run down the lake.

In shorty you are given all of the things you've had to buy for years and for nothing of value to them . . . yet.

What is easy for racers is not always easy for pit people. My task had been made easier. Jim Crow’s was made more difficult. The original plan called for Crow to gas me twice. Making the course faster gave him less time to move. Crow also had to move a greater distance. It took the rest of the day to find a quick enough crosscountry route.

AT LONG LAST, THE RACE

Getting ready for the 1000 was such a hassle that by the time I reached Ensenada, I was too tired for pre-race nerves. Too tired for anything but to get the thing over with.

Ron showed up on time, one day before the start. We spent the morning checking the PE and jetting the engine on the safe side for that long run down the dry lake. About noon, we headed for SCORE headquarters.

At SCORE the racer signs in and they put a hospital-type bracelet on his left wrist. Red is the primary driver. Blue is the secondary driver. The vehicle number and his name appear on the bracelet. This is to keep everyone honest. If someone without the proper ID is caught on the bike the entry is disqualified.

On to the contingency line. SCORE races are professional meets. If you win your class using, say, Product A. the people who make Product A will pay you a specified amount of money, which in turn enables them to use you in an ad endorsing their product. Generally the pay-off is $50 per product/manufacturer. The contingency line is to allow you to sign up for the products you use.

For a sportsman biker, this is an unreal experience. First, the place is jammed with people. The spectators ask about your bike and look at you as if you are a cross between a hero and a lunatic. At the same time, everybody with a product rushes up and asks whether you’re using theirs. If you are, you get more of the product, a decal is slapped on your bike, and a potential ad release is signed. By the time you get to the end, you’ve been showered with so much stuff' (goggles, oil, chains, spark plugs, lights, cables, filters, etc.) you can hardly push your bike. In short, you are given all of the things you’ve had to buy for years and for nothing of value to them . . . yet. Nobody knows you. You haven’t won a damn thing and maybe never will. Far out. (How about spending practice time here? To hell with bike prep, pre-runs and that stuff.)

At the end of this madness, a SCORE official makes sure you’ve actually used the products you've signed up for. He takes your contingency form, and off you go to tech. Tech inspection is a big deal for cars. For bikes, well, SCORE doesn’t really want to know all that much about bikes. They look at the motor to make sure it isn’t a car engine, they put paint on the engine cases and frame because the originals must finish the race, they check for an operating headlight and rear reflector. So much for the bike.

Safety equipment comes next. To race in SCORE events, you must use a helmet that meets Snell or SHCA requirements 1970 or newer; or approved by the SI (Safety Inspector in charge). You must have your name painted on the helmet. They make sure either you or the vehicle are carrying emergency water, rations, and a first-aid kit. That’s it. They don’t specify the type and or what other protective clothing is advisable for bikes. That's up to you. The whole process took about 15 minutes.

After tech, the smart thing to do is sleep. Initially, sleeping proved to be no problem . . . until the sound of rain beating on the roof of the hotel became too loud to ignore. Rain was the one thing we weren’t prepared for. We didn't have riding gear capable of keeping us dry. Our choice of tires wasn’t exactly great for mud.

The more it rained, the more nervous I got. The later it got, the more it rained. By 5 a.m. (our scheduled wake-up time) Ensenada was flooded. The impound area> was flooded. SCORE was silent.

Because SCORE was silent, we had to assume the race would begin. We waterproofed Ron with as many trash bags as we could find and delivered him to the impound area. He hopped up on the fence (the sidewalk was under water) and checked out our PE. It was still there, carburetor deep in muddy water.

The time required to get to my starting point at Nuevo Junction is greater on the highway than on the race course. This forced Jim and me to leave in advance of any word from SCORE about postponement. At noon we received word via radio of cancellation. Figure a two-hour drive out in a 4WD Chevy pick-up. Figure waiting in said truck for six hours with the temperature just above freezing. Figure another two hours for the return to Ensenada.

Neat. Neater was the fact that Ron. trash bags and all. finally ended up in Ojos Negros . . . stuck in the mud. SCORE decided to start the race out there. They allowed the bikes to be trucked and the truck Ron was in got stuck.

Back to Ensenada. After canceling the race, SCORE again disappeared. We loaded our PE back on the trailer and waited. Word finally filtered down, via loudspeaker, that the race would begin the next day at 5 a.m. from the original starting area in Ensenada.

Race day dawned clear and cold. Ron fired the PE and headed for the start. Jim drove me, for the second time, to Nuevo Junction. Plenty of time to think during the two-hour drive. Plenty of time to get worried. For good cause. SCORE said it hadn’t rained on the dry lake side of the mountains. But it was obvious that it had. Was the lake passable? Would my pit crews still be there? Only time would tell.

We arrived at Nuevo about 30 minutes before Ron was due. I spent my time pacing up and down. Jim spent his time yelling at me to get dressed. At the 20minute mark, Roeseler on the Husky and Baker on the Honda flew by. Roeseler stopped for gas. Baker didn’t. The second Husky slid up. Its rider had a broken collarbone. Well, nobody said off-road racing was totally safe. Finally, Ron arrived.

The PE was muddy. Ron threw me the pistol belt with the water and rations. I added a canteen of oil. Ron said something about the handling—something like it wasn’t steering right.

Into the first rock turn and 1 found out what Ron meant about the steering. The front end didn’t push, but you couldn’t hold any particular line. All you could do was pitch it in and bounce over all the rocks you intended to miss. Great.

About 15 minutes out, something dawned on me. Here I was, right in the middle of one of the biggest off-road races ever, and there was no sign of the race. There were no tire tracks ahead. There was only the sound of my motor. There was no one in sight . . . not even to the rear. Nothing. There was no way to judge whether I was doing good or bad. I just had to pace myself and hope it was enough!

I pushed as hard as I could on the way to the summit, which divides the Gulf from the Ensenada or Pacific Ocean side of the peninsula. The Works Performance shocks were working well. The forks crashed and thudded. Funny, they worked fine with the stock rear shocks. No more.

More turns, more rocks. Enter my first sand wash—make that sand wash with rocks. Steering improved with speed but speed didn’t last long. Just as I was beginning to enjoy the race, the engine revved and the rear wheel began to skid. I looked down. No chain. No chain tensioner.

I got down on the ground, found the chain tensioner bent under the swinging arm. Ten minutes later, I had everything straight. A new master link was popped into the chain, I adjusted the tension, and crammed tools back into the Malcolm bag.

Back to the bike. More rocks. More washes. Higher speed. A Bultaco broken down beside the trail. A Honda 440 pitted for gas. Checkpoint Two.

Here I was, right in the middle of one of the biggest off-road races ever, and there was no sign of the race.

As I slid into the check, one official wrote down my number, 345. Another put a chip (piece of paper) into the official beer can taped to the bars. A pat on the back and I was off, looking for Jim Crow. Three miles down the trail I found him, none too soon. I only had Vs of an inch of gas in my tank . . . empty in other words, in only 48 miles. Not too good. Not nearly as good as on the pre-run. Rain-soaked ground eats gas.

The rocks were gone now. Curves with occasional cross-grain took their place. I caught the Honda 440 that gassed up before me and we raced for 10 or 15 miles. He blew by me on every straight. I passed him every place there was a turn or where it was rough. Finally, I pulled ahead. More like it, I thought.

The fast section got faster. Rain softened the cross-grain to the point it could be taken flat out in 5th. in our case, 75 mph. The forks sounded bad, but what the hell, I thought. Reality was slipping away.

Reality returned when I hit a rock I didn't see. Instant wheelie, flat out in 5th. It must have looked neat because I never shut off. It felt neat too, but the price of the thrill was high. By the time the front wheel touched down, it was flat.

In the pits past the checkpoint I found a member of Ron's club. A couple other members were in the race and this man was serving as a pit crew for all of us. I inspected the tire while he adjusted the chain and filled the tank. The tube was done for, so I decided to ride on the flat until I could reach Jim Crow’s next station and my spare wheel, which I earlier stashed in his wagon.

Back to the course. Check Three is near Mexicali. It’s also where you either get on Laguna Salada dry lake or go around or take the original SCORE course. At Check Three, SCORE told me the lake was slippery, but passable. Damn, I thought. Better cut across the lake halfway, then swerve right and find Crow.

The PE would only negotiate the lake one way, flat out in 4th. Flat out in 4th should be 55 mph or so. On the lake it was more like 35 mph and a giant rooster tail.

Even though I ran through a lot of water, mud packed in under the fenders. The front was so heavy it dragged on the tire. The rear fender folded under and was being worn away. Amazing. Up ahead, I saw a group of stuck bikes. Rather than stop, I headed for shore—immediately! The closer to shore I got, the more pumped I got. I’d gambled and won. I cut off'a lot of the original course and was going to get away with it. Two hundred yards to go; 100 yards. Instant halt.

What the hell? I looked down and could see only mud. Ten minutes of mud removal revealed the problem. My pit support had left the cotter pin out of my rear axle nut. He also didn’t tighten the nut. It fell off and my chain derailed just when I needed it most. Ten more minutes and the bike was repaired. An hour later I got out of the lake. See. when you get stuck in a pile of mud, you stay stuck. Wheels turning slowly pick up mud so quickly you can only go 5-10 feet per cleaning section. One hundred yards takes about an hour.

More bad news. An hour in the mud uses up gas at an unbelievable rate. When I reached the shore, I was almost out. Distance covered, 20 miles. I couldn’t believe it. Amost three gallons to go 20 miles. I found a rider whose bike had seized in the mud along the edge of the lake. He gave me his gas and a message for his crew. I owe him an apology. I didn’t make it either, so I couldn’t relay his position until late at night.

(Continued on page 116)

Continued from page 84

That’s right, his gas wasn’t enough either. Oh, it would have been if Crow could have made it to the edge of the lake. But he couldn’t. Too much mud. 1 ran out of gas halfway down Laguna Salada. I had gambled and lost. What a letdown. I sat there and watched the first single-seaters blast by. Ivan Stewart was the first. He must have been doing 100 mph, totally out of control. He spun as he passed me, recovered, and kept going. What a show. What a frustrating show . . . watching others succeed with style where you had failed.

After about an hour, a gift appeared on the horizon. A single-seater was floundering, digging in. More throttle. More rpm. More wheelspin. Clogged oil cooler. Big noise and cloud of black smoke. Gas, I thought. All I have to do is walk out there and get it.

Because of the distance, probably two miles, I elected to take a canteen, bring it back, then ride my bike to the car. Great theory. Hard to pull off, however. It took me an hour to slog to the single-seater. I gave him water, he said he’d give me gas. We began disconnecting the fuel line when a better deal slid up, or rather got stuck. Halfway between the single-seater and the shore was a Baja bug, stuck but otherwise healthy. The driver was alone. Help him out, I thought, and he’ll deliver the gas, which is exactly what he said.

It took an hour to get the car out. When it moved I climbed on the roof (or rather hung onto the roof) and stood on the engine. No way to get inside. He blasted off, I yelled directions, he didn't hear them. He hit a bush, the car bounced up in the air and I did an endo off the roof. He circled, saw me get up, and took off. Now I could add a black eye and loss of vision because of a cut on my forehead to the list of my problems.

I'd lost 12 hours. Going the safe, original way would have cost 30 minutes. Bad gamble.

Rather than quit, I went back to the bike, took the gas tank off, and spent another hour walking out to the singleseater. I gave the driver more water, he gave me three gallons of gas. Back to the bike, somewhat slower this time because three gallons of gas weighs 18 lb. I kicked the PE over just as the sun set, thankful I at least had oil with me. I’d lost 12 hours. Going the safe, original way would have cost 30 minutes. Bad gamble.

I rode along the edge of the lake after dark, racing cars, trucks and anything else that came along. With my light I had the edge on most of them. (Thanks, Len.) At Tres Posos I bummed more gas, got some food and drink from some really great people (thanks, whoever you are) and sped off, in rocks this time.

After a time, the light bouncing off the rocks caused me to hallucinate. I saw rabbits doing things I know they can’t. The ground moved. Bushes moved. Then the light flashed on something familiar. A course marker. A broken bike (Carl Cranke’s Penton 125). I stop, Carl approaches. He tells me he’s been in the same spot since noon. No one would stop. I gave him water and found a four-wheel drive that would take him to Tres Posos (a shack with three wells ... a big deal, in other words).

More rocks. More washes. Directions from a single-seater pilot, El Chinero. Thank God, I thought. El Chinero. Where I get off. Pam, my usually calm but now hysterical companion greeted me, hopped on the back, and took me to our pit. Hansen looked strained. Ron asked about the bike as he changed the tire. I fell to the ground and worked on the chain. Pam wiped the mud and blood off my face. Ron sped off into the night. For me, it was over; a 12!/2-hour nightmare was over.

Ron got the bike as far as Trinidad, 150 miles plus change from the finish. At that point we decided to quit. We weren’t prepared for the cold. Cold meant Ron couldn’t speak and had borderline frostbite of the face and hands. I couldn’t continue because the hikes on the lake left me with multiple blisters (bleeding) on both feet. Besides, it was foggy and there was no way we could go fast enough to beat the cut-off time.

What a frustrating show . . . watching others succeed with style where you had failed.

Team Husky (Larry Roeseler and Mitch Mayes) won the race. Baker’s rapid Honda burned up its clutch and stopped. Bruce Ogilivie and Bob Rutten were 1st 250 and 4th overall, behind Ivan Stewart. Ed Rodine ended up 1st 125.

Some reflections: Baja racing is unusual. It’s tough but in a unique way. There is little in the way of stimulation from other racers to help keep your speed up. There is no help if you break down. Failure of the smallest, cheapest component can cause a dnf. And the terrain changes so quickly, so completely, there’s no way to master it. All you can do is play it safe, have a back-up for everything, and hang on long after you would normally give up. The Baja 1000, then, is a challenge. It’s a test of mechanical preparation, organization, and guts ... a test no entrant will ever forget.

If it hadn’t been for the rain, and the cotter pin, and the missing fuel stop, and the cold, and the mud . . . yes, I’ll do it again. löl

View Full Issue

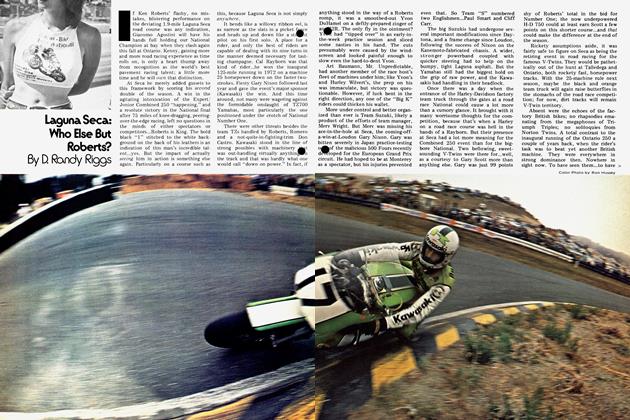

View Full Issue