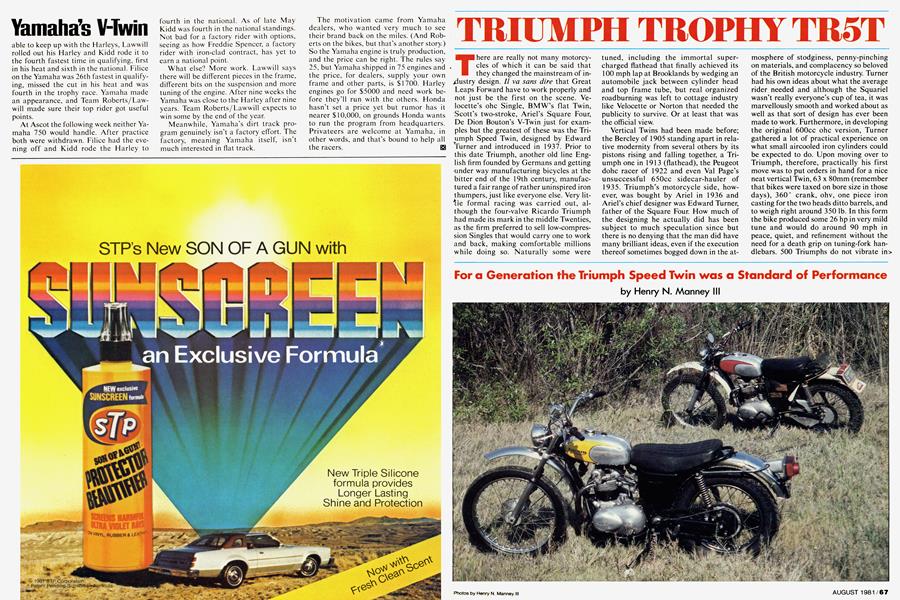

TRIUMPH TROPHY TR5T

For a Generation the Triumph Speed Twin was a Standard of Performance

Henry N. Manney III

There are really not many motorcycles of which it can be said that they changed the mainstream of industry design. Il va sans dire that Great Leaps Forward have to work properly and not just be the first on the scene. Velocette's ohc Single, BMW's flat Twin, Scott's two-stroke, Ariel's Square Four, De Dion Bouton's V-Twin just for examples but the greatest of these was the Triumph Speed Twin, designed by Edward Turner and introduced in 1937. Prior to this date Triumph, another old line English firm founded by Germans and getting under way manufacturing bicycles at the bitter end of the 19th century, manufactured a fair range of rather uninspired iron thumpers, just like everyone else. Very litlle formal racing was carried out, although the four-valve Ricardo Triumph had made its mark in the middle Twenties, as the firm preferred to sell low-compression Singles that would carry one to work and back, making comfortable millions while doing so. Naturally some were

tuned, including the immortal supercharged flathead that finally achieved its 100 mph lap at Brooklands by wedging an automobile jack between cylinder head and top frame tube, but real organized roadburning was left to cottage industry like Velocette or Norton that needed the publicity to survive. Or at least that was the official view.

Vertical Twins had been made before; the Bercley of 1905 standing apart in relative modernity from several others by its pistons rising and falling together, a Triumph one in 1913 (flathead), the Peugeot dohc racer of 1922 and even Val Page's unsuccessful 650cc sidecar-hauler of 1935. Triumph's motorcycle side, however, was bought by Ariel in 1936 and Ariel's chief designer was Edward Turner, father of the Square Four. How much of the designing he actually did has been subject to much speculation since but there is no denying that the man did have many brilliant ideas, even if the execution thereof sometimes bogged down in the at-

mosphere of stodginess, penny-pinching on materials, and complacency so beloved of the British motorcycle industry. Turner had his own ideas about what the average rider needed and although the Squariel wasn't really everyone's cup of tea, it was marvellously smooth and worked about as well as that sort of design has ever been made to work. Furthermore, in developing the original 600cc ohc version, Turner gathered a lot of practical experience on what small aircooled iron cylinders could be expected to do. Upon moving over to Triumph, therefore, practically his first move was to put orders in hand for a nice neat vertical Twin, 63 x 80mm (remember that bikes were taxed on bore size in those days), 360° crank, ohv, one piece iron casting for the two heads ditto barrels, and to weigh right around 350 lb. In this form the bike produced some 26 hp in very mild tune and would do around 90 mph in peace, quiet, and refinement without the need for a death grip on tuning-fork handlebars. 500 Triumphs do not vibrate in> such a soft state of tune; I rode a prewar Tweed Spin one time in England and was even happier than the cops who used them for 20 years give or take a bit. At any rate Turner was crafty enough to make the bike look pretty much like the raft of twinport Singles that were the rage at that time, Englishmen being what they are about innovations, and public acceptance was immediate. Easy-starting (if you can't start a 500 Triumph you can't start anything), superlative smoothness, exceptional flexibility, decent torque, and performance ahead of all but temperamental “cammers” made Turner's Twin the bike of the year. Of course there were a few drawbacks well-known to Triumph owners; sticky clutches, frequent tappet adjustments, a point-setting ritual out of the Book of Kells . . . but 1937 being 1937 the competition had all those and several more! The following year, Turner capped his achievement by bringing outthe famed Tiger 100, a slightly tweaked model with higher-lift cams, better breathing etc that was individually dynoed at 34 bhp approx at 7000 and could and would do an honest 100 mph up out of bed at midnight, so to speak, and at a highly competitive price too. The Tiger became the dream bike of every aspiring roadburner and what it did to the Singles market was nobody's business; as soon as possible the competition got into the act (translation; after the war) to get its market back.

The Unpleasantness on the Continong, however, did more than screw up every-

body's production plans. The British Army, which rigidly had clung to singleshot Lee Enfields (more sporting) left over from the seige of Mafeking, also clung rigidly to the illusion that flathead Singles were the only way to go for the military. After a series of demonstrations that showed Turner's new 350 T did the job better and weighed something like 100 lb. less, the Army grudgingly put in an order for a thousand or so but then the Coventry factory, together with Coventry Cathedral close by, was blown off the map by a night visit from the Luftwaffe. Naturally enough Triumph was a trifle delayed in getting back into operation and by that time BSA and Norton had the contracts sewed up, what remaining slack there was being taken up by early deliveries of the ubiquitous Jeep. A slightly remorseful War Office then handed Triumph a contract to make x number of portable or semi portable generator sets for field use or to be carried about in Lancaster bombers to charge the batteries. Actually the Crosley engine, now Homelite, was developed for similar use in BÍ 7s and B29s. Anyway, as the generators were rather hefty, a fan-cooled version of the Speed Twin was found to do the job, a Single being unsuitable as it gradually unscrewed itself, no fun over Dusseldorf with the air full of Messerschmitts. The whole plot was still heavier than it needed to be so some bright lad decided to kill two birds with one stone and cast up the cylinders and heads out of silicon-aluminium alloy, better cooling also being a bonus. As an

afterthought, the ignition-side crankshaft bushing came under scrutiny and it too was replaced with a nice ball bearing match the drive side. Airmen who regarded these neat little units with speculative eyes were sometimes deterred by the prominent shroud-mounting boss with integral bolt hole slap in the middle of the fins but the country that produced the Narvik commando operation wasn't going to be deterred by a little thing like that; a little work with a file plus a nice coating of Stove Black WD Other Ranks For The Use Of plus a little Castrol R soon gave passable imitation of an iron top end, even when a cup or so of rust particles helped to ward off the vigilant busies. Hm.

It wasn't any accident, therefore, when the first Senior Manx GP after the war was taken by Irishman Ernie Lyons on a Tiger 100 .. . his Tiger 100 and a prewar one at that but fitted with an engine looking suspiciously like one of the ex-RAF units. Of course the idea had never occurred to Triumph and all the more embarrassing as Triumph had never won on the Island before. Little time was wasted in hiring racer David Whitworth (no relation to the wrenches) to develop a new bike to be called the GP, a customer's racer based very closely on Ernie's trick Tiger but incorporating factory improvements. Issued in 1947, the GP suffered from being essentially a racing bike based all too plainly on a modified production article but scored quite a few successes while the rest of the folks were catching up. Many of the complaints were about the roadholding, or lack of same, as to be perfectly truthly Triumphs have always Kbeen a little individual in their handling ever since the Riccy Triumph, the girder fork of which worked back and forth against its spring instead of up and down like a good Christian mechanism. Anyway, Triumphs had teles now even if they didn't do much damping and shortly the .works introduced its infamous spring hub, which meant that the rider traded about 1 inch of undamped movement at the back for a jolly increase in unsprung weight and a lot of sudden wear and slop in a sensitive location. Taking a spring hub apart was worse than defusing bombs but I always liked mine as it was much more comfortable than a rigid frame but racing is a different situation, especially to those used to the hairline precision of girders and a rigid back end. A quick fix, universally popular among those still running in English vintage events, was a combination of Norton Roadholder forks (which stopped 'most of the nonsense) plus, a little later, a grafting on of a Manx swing arm setup from Nortons recently vacated by their engines. In fact, the popular Triton, of which you may of heard, is a Norton frame with a Tiger 100 or GP shoehorned in. It wasn't that Norton engines were particularly unreliable at that time but the only way Formula 3 car racers (Coopers etc) could get a double-knocker engine was to buy the whole Manx.

Triumph had always been in regularity events, just like many of the factories that don't do regular racing, and the Dirt Dept

of Comps, had done a little crafty measuring around the GP and also took to attending war surplus sales of late RAF equipment. The result was the tidy all-alloy TR5 dirt bike, scaling very light around 305 lb. for British machinery, and even with or in spite of the spring hub scoring a great success in the 1948 ISDT. Copies were duly marketed and I had one around 1950 sometime square barrel and all. It had high ground clearance, a tucked-away (sort of) exhaust system that provided central heating for one leg, and very short gears as well as wheelbase. This Trophy as it was called was an absolute delight in city traffic as it could be flicked about and could be run in top down to about 10 mph without snatching; on the dirt I was very much an amateur but the friend to whom I sold it (the rat) upon going to Europe had great fun on the fireroads ... he may have even run it in the Big Bear once. At any rate Triumph, using bikes based on this model, won four consecutive manufacturer's Team Prizes from '48 through '51 in the ISDT plus several other individual places, some of these efforts being on Cheney-framed specials with rather bigger engines as by this time BSA had taken over and the engines at least had to look like production ones. So it was good-bye to the square-barreled alloy ones. Somewhere in England there is an airfield. . . .

The demands of the American market in particular meant an increase in capacity and/or an increase in tune, which meant that the Bonnevilles and Daytonas came into being (they deserve an article of

their own), the bigger engined Twins (ditto), the work of Johnson Motors of Pasadena in promoting the marque (ditto), the numerous competition successes (ditto) and the rise of Triumph Desert Sleds (ditto). The collapse through overextension and bad management of BSA-Triumph-Ariel et Cie has been done as has the checquered history of the Meriden CoOperative. However the 500 lives on, not least in a Japanese speedway league that uses the pre-unit construction engines and John Caliccio of Costa Mesa (JRC Engineering) has a thriving business in 500 parts, sharing with thousands of enthusiasts the love for the sweet-running little beast. However, the factory had one last clap in 1973, when the ISDT was held in the Berkshires under American supervision. A hastily assembled British-American team entered 12 TR5Ts, basically BSA frames with slightly detuned Tiger 100 units fitted, and finished in the team rankings second behind the Czechs, I think, the best showing for many years. These bikes were pretty trick with Betor forks, Rickman wheels, duplicated ignitions and a few other goodies and if the Art Editor sees fit to print one of the photos of our Salon bike, a production 1973 TR 5 T, you may see a veritable example of the ISDT team lurking behind it.

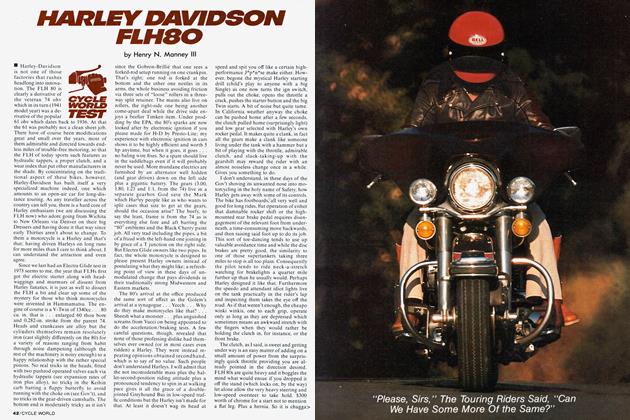

Essentially they are the same with BSA centre spine oil tank frame, iron-barrel Tiger engine (69 x 65.5mm since some time back) a little calmer however, shorter chassis than the road bikes . . . one expert said that it was a rehash of an old 350 frame, and suspension by swing arm and teles jacked up a bit to give more ground clearance. This particular TR5T is a unit construction one of course, a mod which came in on the 3T and lacks from new the trials tyres, skid plate, tachometer, battery and a little of its newness. Owner Chuck Johnson bought the bike as a heap of bits; the former owner having put a hole through a piston while doing a little half mile as the ignition was set wrongly, and straightaway set to work. A Barnett clutch was fitted, all the badly worn bits slung out, and in a month or so the mistakes (bodges) of previous owners had been sorted out and the TR5T was running again. Capacity is 490 cc plus a slight re< bore to clean up the cylinders, comp, ratio is 9:1, the Amal 930/87 pulls strongly on the centre needle slot, sprocket ratios are 18 (gb) and 53 (rear), it wears 3.00-21 front and 4.00-18 back, brakes are 7 and 6 in. respectively and it weighs an alleged 322 lb. dry. How the ISDT bike can have a, 40 lb. silencer and weigh just over 300 is one of those mysteries. Actually I owned the “Yellow Triumph” for a spell through one of those complicated deals and foun^ it more or less the same as the all-alloy 1950 Trophy except of course heavier. The high seating position makes the TR5T a bit tippy in traffic, a problem made more awkward by the kick-starter's tendency t^ get caught in the pants cuff, but the short gearing (857 rpm for IO mph in top) makes life a lot easier in town than a fairing clad BMW, for example. Triumph design dictates that you move the Aswan Dam before changing counter-shaft sprockets but perhaps it is just as well in view of high speed handling with the re-' duced rake angle. The small tank (2.5„ gal.) is a bit of a nuisance but it is such a sweet-running bike that a few tiny faulty can be forgiven. The ride is sort of hard and choppy, a characteristic that could be modified without too much difficulty, but only the English could go far off the roa<$ with those forks. Still, when you think of^ four-stroke reliability and all those acres of desert .. . does anyone out there havg one of those square-barrel alloy engines in good nick?

continued on page 95

The TR5T, a Pom's idea of a dirt bike, did not have a very long run as most folks' were already running overbored 650s or 750s in the desert, a longer chassis being" needed to bull their way through the sand washes. Furthermore the light disposeable* Japanese invasion was in full swing and it is much easier to lift a 250 lb. bike off oneself than a 350 lb. 500. Thus the Trophy passed into history along with BSATriumph's final paroxysms, unlamented except for its fans. Faithful fans who feel that breeding does count for something"* Lovely, isn't it?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

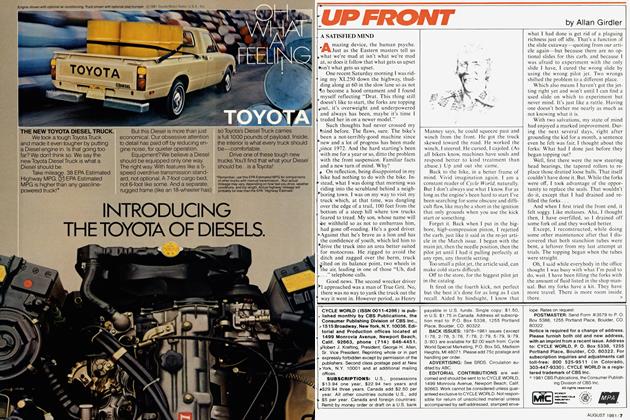

Up Front

Up FrontA Satisfied Mind

August 1981 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1981 -

Book Review

Book ReviewBrooklands Behind the Scenes

August 1981 By Henry N. Manney III -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

August 1981 -

Motorcycle Insurance

Motorcycle InsuranceWhat It All Means, And How To Know What You Need.

August 1981 By David D. Mallet -

Motorcycle Insurance

Motorcycle InsuranceNot All Motorcycle Insurance Companies Are Alike. Some Take Your Money And Go Out of Business.

August 1981 By John Ulrich