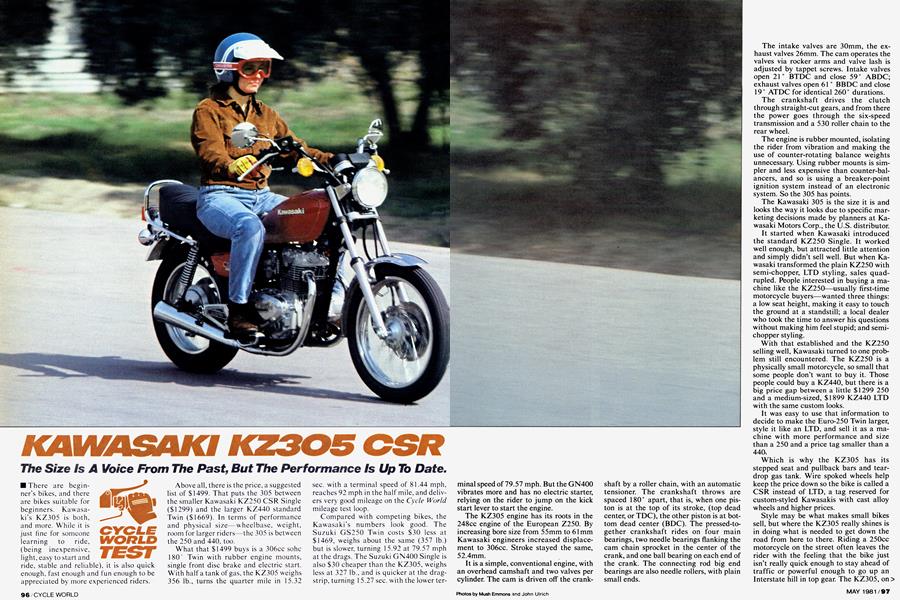

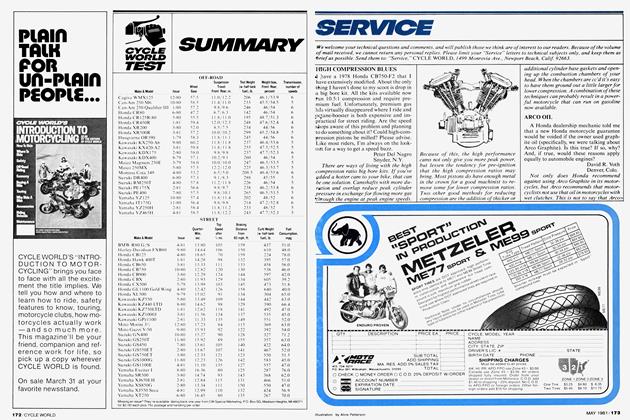

KAWASAKI KZ305 CSR

CYCLE WORLD TEST

The Size Is A Voice From The Past, But The Performance Is Up To Date.

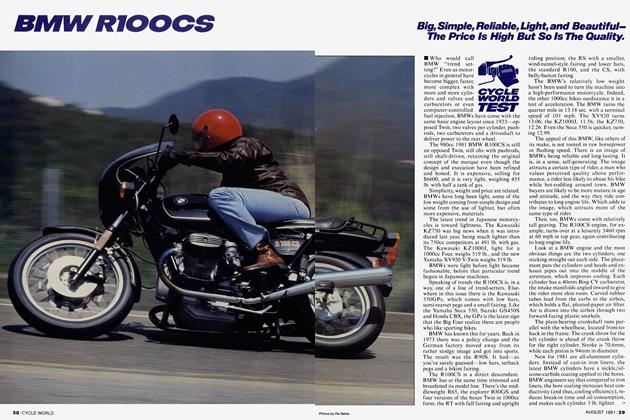

There are beginner’s bikes, and there are bikes suitable for beginners. Kawasaki’s KZ305 is both, and more. While it is just fine for someone learning to ride, (being inexpensive, light, easy to start and ride, stable and reliable), it is also quick enough, fast enough and fun enough to be appreciated by more experienced riders.

Above all, there is the price, a suggested list of $1499. That puts the 305 between the smaller Kawasaki KZ250 CSR Single ($1299) and the larger KZ440 standard Twin ($1669). In terms of performance and physical size—wheelbase, weight, room for larger riders—the 305 is between the 250 and 440, too.

What that $1499 buys is a 306cc sohc 180° Twin with rubber engine mounts, single front disc brake and electric start. With half a tank of gas, the KZ305 weighs 356 lb., turns the quarter mile in 15.32 sec. with a terminal speed of 81.44 mph, reaches 92 mph in the half mile, and delivers very good mileage on the Cycle World mileage test loop.

Compared with competing bikes, the Kawasaki’s numbers look good. The Suzuki GS250 Twin costs $30 less at $1469, weighs about the same (357 lb.) but is slower, turning 15.92 at 79.57 mph at the drags. The Suzuki GN400 Single is also $30 cheaper than the KZ305, weighs less at 327 lb., and is quicker at the dragstrip, turning 1 5.27 sec. with the lower terminai speed of 79.57 mph. But the GN400 vibrates more and has no electric starter, relying on the rider to jump on the kick start lever to start the engine.

The KZ305 engine has its roots in the 248cc engine of the European Z250. By increasing bore size from 55mm to 61mm Kawasaki engineers increased displacement to 306cc. Stroke stayed the same, 52.4mm.

It is a simple, conventional engine, with an overhead camshaft and two valves per cylinder. The cam is driven off the crankshaft by a roller chain, with an automatic tensioner. The crankshaft throws are spaced 180° apart, that is, when one piston is at the top of its stroke, (top dead center, or TDC), the other piston is at bottom dead center (BDC). The pressed-together crankshaft rides on four main bearings, two needle bearings flanking the cam chain sprocket in the center of the crank, and one ball bearing on each end of the crank. The connecting rod big end bearings are also needle rollers, with plain small ends.

The intake valves are 30mm, the exhaust valves 26mm. The cam operates the valves via rocker arms and valve lash is adjusted by tappet screws. Intake valves open 21° BTDC and close 59° ABDC; exhaust valves open 61 ° BBDC and close 19° ATDC for identical 260° durations.

The crankshaft drives the clutch through straight-cut gears, and from there the power goes through the six-speed transmission and a 530 roller chain to the rear wheel.

The engine is rubber mounted, isolating the rider from vibration and making the use of counter-rotating balance weights unnecessary. Using rubber mounts is simpler and less expensive than counter-balancers, and so is using a breaker-point ignition system instead of an electronic system. So the 305 has points.

The Kawasaki 305 is the size it is and looks the way it looks due to specific marketing decisions made by planners at Kawasaki Motors Corp., the U.S. distributor.

It started when Kawasaki introduced the standard KZ250 Single. It worked well enough, but attracted little attention and simply didn’t sell well. But when Kawasaki transformed the plain KZ250 with semi-chopper, LTD styling, sales quadrupled. People interested in buying a machine like the KZ250—usually first-time motorcycle buyers—wanted three things: a low seat height, making it easy to touch the ground at a standstill; a local dealer who took the time to answer his questions without making him feel stupid; and semichopper styling.

With that established and the KZ250 selling well, Kawasaki turned to one problem still encountered. The KZ250 is a physically small motorcycle, so small that some people don’t want to buy it. Those people could buy a KZ440, but there is a big price gap between a little $1299 250 and a medium-sized, $1899 KZ440 LTD with the same custom looks.

It was easy to use that information to decide to make the Euro-250 Twin larger, style it like an LTD, and sell it as a machine with more performance and size than a 250 and a price tag smaller than a 44(X

Which is why the KZ305 has its stepped seat and pullback bars and teardrop gas tank. Wire spoked wheels help keep the price down so the bike is called a CSR instead of LTD, a tag reserved for custom-styled Kawasakis with cast alloy wheels and higher prices.

Style may be what makes small bikes sell, but where the KZ305 really shines is in doing what is needed to get down the road from here to there. Riding a 250cc motorcycle on the street often leaves the rider with the feeling that the bike just isn’t really quick enough to stay ahead of traffic or powerful enough to go up an Interstate hill in top gear. The KZ305, on the other hand, does have enough power to pass and stay in front of traffic, or to roll up steep grades in sixth gear at 65 or 70 mph. Brisk acceleration or a fast pass on a two-lane road still demands a lot of rpm, but if the rider wants to use the revs, the 305 will gladly run hard, at or near redline and even when the bike is run at 70 or 75 mph for hours on end, up and down mountain passes as well as along flat stretches and against headwinds, as well as in calm, the rider can still expect to get over 50 mpg.

All the while, the two rearview mirrors remain clear and the rider is unbothered by buzzing vibration. The engine does vibrate—touching a boot toe to the cases while riding will affirm that—but the rubber mounts just don’t let the high-frequency shaking get to the pilot.

The two 32mm Keihin CV carbs work a lot better than the 36mm CVs of the same brand seen on the last KZ440 tested, in August 1980. With full choke and no throttle, the KZ305 starts right up when cold. But if the rider opens the throttle even a little during a cold start, the engine refuses to fire.

While better than the 440’s carbs, the KZ305’s carburetors are still not perfect. They are precise and don’t cause bucking at small throttle openings and steady, low road speeds. But like many CV carbs, they do have a hesitation felt when the rider closes the throttle, as to slow momentarily, then re-opens the throttle. It is especially noticeable at highway speeds.

Then, too, the bike actually seems to run better with a little less than full throttle. Pin the twist grip against the stop in top gear and the bike accelerates, but back off the throttle a tiny bit and it accelerates harder and runs smoother. That’s probably because the carbs are set up lean to meet emissions regulations.

There are limits to how good the suspension will be on an economy motorcycle, but the KZ305’s suspension is surprising. Small bump compliance is good, and handling is excellent. Because the KZ305 is light and has a short wheelbase (54 in.), it is easy to put into a turn. Once in a curve—even a fast, sweeping turn—the bike is stable and doesn’t have any suspension-caused problems. It doesn’t wallow or wobble, and cornering clearance is very good.

Ridden in the sport mode, the 305 can be fun even for a hard-bitten superbike rider. There’s something sporting and exciting about running a bike up through the gears, nicking the 10,000 rpm redline with the tachometer needle before upshifting, hearing the engine gain speed one gear after another.

Do that on a superbike much, and you’re apt to collect a book of tickets.

But on the KZ305 the rider can even let ’er wind in town and still stay close to being within the speed limits. On less heavily-patrolled, deserted roads, the Kawasaki will move right along, given enough rpm. It is just plain fun.

It’s also reasonably comfortable. Being a smaller bike, the seating position can seem cramped for taller riders after a few dozen miles. The rider can put his feet on the passenger pegs for relief. It’s harder to cure something like a rock-hard seat, but happily, the KZ305’s seat is good, better than the seats found on most bikes in its price and size range. One of our test riders took the 305 on a 250-mi. ride without complaining.

On that day trip, that particular rider had a chance to try the 305’s lights on open country roads without streetlights and with little traffic. Some small machines have marginal headlight power, even for the moderate speeds they can attain. But the KZ305’s 50-watt high beam and 35-watt low beam are adequate for cruising at 60 mph. With the headlight beam selector switch carefully positioned so both beams will turn on at once, lighting is good.

Instrument lighting is also up to the task, making it easy to read odometer, speedo and tach at night.

Braking performance was excellent, the single front disc and rear drum stopping the Kawasaki in short distances with no panic. It might be that one of the 250s with a drum front brake can stop in as short a distance as the Kawasaki will, but some riders want a disc brake and the Kawasaki has one.

What we found, then, was that the KZ305 delivered on its claims and performed without problem.

What it also did was cause us to sit back and reflect for a moment on what has happened to beginner bikes over the last 15 years.

It used to be that a guy would start out on a 50 or a 90 or a 125 and work his way up through a 175 and a 250. That done, he could move on to one of the high-performance 305s, like the Honda Super Hawk or the Yamaha Big Bear Scrambler, or maybe even a Bridgestone 350. In those days, the Suzuki X-6 Hustler was a highperformance machine, even at 250cc.

The 305s grew to 350 and 400 and eventually to 440, superbikes grew from 750cc to 900cc to lOOOcc to llOOcc, big bikes went from being 500cc up to 750cc, and the little beginner bikes just kind of went away. When a superbike was a Honda CB750, a CB100 was a beginner bike. Now that a superbike is a Suzuki GS 1100, a CB125 may still be a beginner’s bike, but most beginners buy Yamaha XS400s or Suzuki GS250s or a Kawasaki KZ305.

The beginner bikes of today are faster and quicker and smoother and more reliable than the high-performance middleweights of the Sixties and early Seventies. The KZ305 is a more refined, better motorcycle than a 1965 Honda 305 Super Hawk.

Which all points out just how far motorcycles and motorcycling has come.

Or, put another way, the Kawasaki 305 does what it does as well as it does because we expect so much more now, because it has to work to sell.

It does work. It will sell. And if we were looking for a light, economical, fun bike, we’d buy it in a minute. S

KAWASAKI KZ305 CSR

$1499