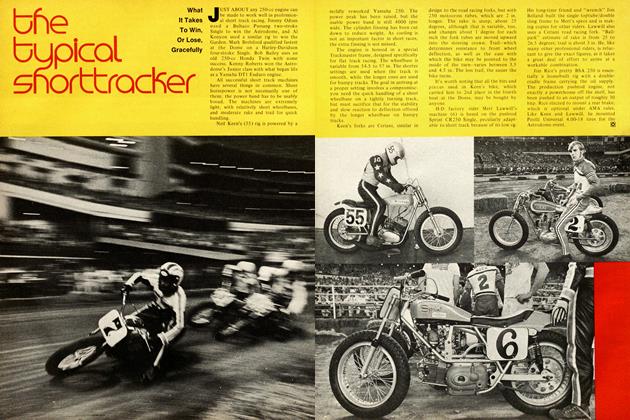

AFM Six-Hour

Team Honda Wins on the Racetrack— and in the Scoring Tower

John Ulrich

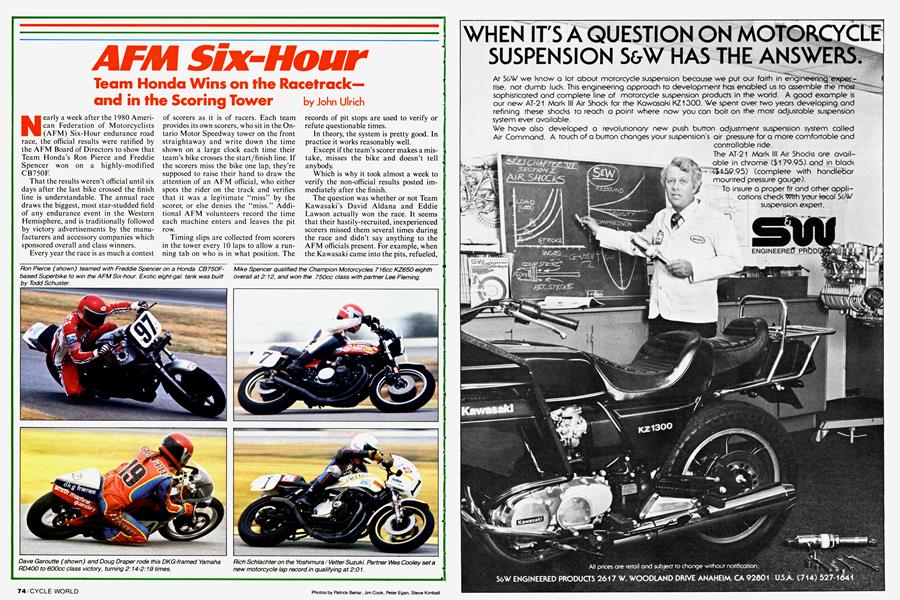

Nearly a week after the 1980 American Federation of Motorcyclists (AFM) Six-Hour endurance road race, the official results were ratified by the AFM Board of Directors to show that Team Honda's Ron Pierce and Freddie Spencer won on a highly-modified CB75OF.

That the results weren’t official until six days after the last bike crossed the finish line is understandable. The annual race draws the biggest, most star-studded field of any endurance event in the Western Hemisphere, and is traditionally followed by victory advertisements by the manufacturers and accessory companies which sponsored overall and class winners.

Every year the race is as much a contest of scorers as it is of racers. Each team provides its own scorers, who sit in the Ontario Motor Speedway tower on the front straightaway and write down the time shown on a large clock each time their team’s bike crosses the start/finish line. If the scorers miss the bike one lap, they’re supposed to raise their hand to draw the attention of an AFM official, who either spots the rider on the track and verifies that it was a legitimate “miss” by the scorer, or else denies the “miss.” Additional AFM volunteers record the time each machine enters and leaves the pit row.

Timing slips are collected from scorers in the tower every 10 laps to allow a running tab on who is in what position. The records of pit stops are used to verify or refute questionable times.

In theory, the system is pretty good. In practice it works reasonably well.

Except if the team’s scorer makes a mistake, misses the bike and doesn’t tell anybody.

Which is why it took almost a week to verify the non-official results posted immediately after the finish.

The question was whether or not Team Kawasaki’s David Aldana and Eddie Lawson actually won the race. It seems that their hastily-recruited, inexperienced scorers missed them several times during the race and didn’t say anything to the AFM officials present. For example, when the Kawasaki came into the pits, refueled, took a lap and then re-pitted for a tire change, the tower scorers recorded it as being one lengthy pit stop, not two short stops separated by a lap on the course.

Kawasaki protested. The AFM deliberated, giving Kawasaki a lap when it could be collaborated by some other means— such as the official pit-in/pit-out times taken by AFM officials—and not giving them a lap when that lap was lost solely due to the error of Kawasaki’s scorers. The AFM system puts the responsibility on the team’s scorers.

Which left the moral issue, as AFM board members were soon calling it, of whether or not Kawasaki won on the track and lost in the tower.

Complicating matters was the fact that the 1980 six-hour was actually five hours, 40 minutes long, red-flagged after a messy straightaway collision and crash between the Yamaha RD of Tom Shanahan and the 458cc CB400F Honda of Bill Silver, wherein Shanahan’s bike suddenly stopped accelerating (Shanahan missed a shift) and Silver’s bike continued to accelerate into the rear of Shanahan’s bike. Silver suffered a broken arm, concussion and a cracked vertebra, but looked much worse lying sideways 10 feet off the fast line on the straight. So the race was stopped, Silver was evacuated via helicopter and confusion reigned.

The race scoring was backed up to the last full lap prior to the red flag. The final decision gave Honda the win by—get this—one second.

The official results also show the Team Yoshimura Suzuki of Wes Cooley and Rich Schlachter finishing ninth. In fact, Cooley qualified first with a blistering 2:01 lap time (faster than Cooley’s set-in-1979 absolute motorcycle lap record for the 3.19-mile Ontario course of 2:02 and his Superbike record of 2:06.25, also set in 1979). Hampered by the wrong rear tire choice for the start of the race, Cooley was second to Spencer on lap 10, third to Spencer and Lawson on lap 20, first by lap 30 and then third behind the Honda and the Kawasaki for laps 40 through 140, meeting disaster shortly afterwards by colliding with an RD Yamaha which took an erratic line at the entrance of turn 16.

The smaller bikes—RDs, XL500 Hondas, TT500 Yamahas—made life interesting for the big-bike riders throughout the race. You could see it time after time, as the riders of smaller, lighter, more agile, slower bikes took wide entrances to turns, inviting Superbike pilots to stuff it past inside, and then slammed the door by heading for the apex on a line intersecting the typical course taken by the big bike riders. Using all the track, the small bike riders in general were a serious hazard to a Superbike rider who wasn’t careful and who didn’t pickJ the right time to pass. Once committed with a big, heavy Superbike, it isn’t so simple to change direction, as several pilots discovered by crashing. On the other hand, the small bike riders constitute the biggest class and thus pay the majority of the bills for the race, which is run by volunteers.

Besides Cooley, Lawson and Spencer also qualified under the previous Superbike lap record, setting the stage for the fastest six-hour pace in history. Indeed, if you weren’t turning 2:07s or close to it during the race, you weren’t in the hunt for the overall lead. >

The 750 class was just as close and hectic. Mike Spencer (partner Lee Fleming) qualified the Champion Motorcycles 717cc Kawasaki KZ650 at 2:12, what used to be a good Superbike time. Carry Keoshgerian (partner Steve McClenon) was close behind on the M.A.C. Products/ HyperCycle sohc Honda CB750, at 2:13. In the race, Spencer turned several 2:1 Is and with Fleming led the 750cc class at every 10-lap interval except lap 90, where Keoshgerian and McLenon led. As the race drew to a close, the Spencer/ Fleming machine—slowed by tire troubles from the earlier blistering pace—was passed by the Hyper-Cycle Honda. Keoshgerian, too, was experiencing tire troubles and ran off turn 10 while leading the class, tipping over. That put Spencer/ Fleming into first-in-class according to the scoring paperwork and set the stage for another protest: As the red flag appeared, Fleming pulled into the pits for a battery change (they ran total loss ignition). The AFM gave first to Fleming/Spencer, with Keoshgerian/McClenon second. The Team Cycle World Suzuki project Suzuki GS750 ridden by Mark Shelton and John Ulrich held third in class from lap 40 (except for being second on lap 60) and was credited with finishing third in class. (More on the bike in a future issue).

The only class win without controversy came in the 600cc division, won by Doug Draper and Dave Garoutte on the Smith Machine and Quandary Yamaha. The bike, used an RD400 engine modified by Bill Smith in a monoshock TZ250 frame built by Garoutte. It weighed 245 lb. with gas, had a 6-gal. tank with quick-fill fittings, delivered 24 mpg, ran without hitch one hour between stops (average pit stop length 25 seconds) and won the class going away with average 2:18 lap times and a best race lap of 2:14.

continued on page 86

continued from page 79

The best finish by a privateer team al-” most went to Chuck Parme and Whitney Blakeslee, on Parme’s Kawasaki KZ1000 Superbike sponsored by Champion Motorcycles, Graham’s Sheet Metal and KalGard. With Blakeslee riding, the team was third overall on the lap before the red flag, when the bike holed a piston and be-, came a Triple. Dennis Smith, riding a GS1000S Superbike (which he built him" self out of his private tune-up shop in Torrance, Calif., Cycle Tune) passed Blakeslee for third overall. Blakeslee/ Parme finished fourth. Smith, who qualified fifth at 2:08 to Parme’s fourth-inqualifying 2:07, rode with 1978 six-hour winner Reg Pridmore. Harry Klinzmanm and David Emde rode the Racecrafters KZ1000 to fifth overall, ahead of Steve Mallonee/JefT Haney on a Team Honda Superbike, in Haney’s first ride on a Superbike. Privateers Kerry Bryant and Wendall Phillips were seventh on Bryant’s Superbike, with Draper and Garoutte? eighth on their RD-powered machine.

It’s interesting to note that in 5 hours, 40 min., the Honda of Spencer and Pierce lost just 4 minutes, 30 seconds in elapsed time (including time spent entering and exiting pit row) in refueling and tirechange stops.

It’s also interesting to note that the top four finishers in the 750 class (Spencer/ Fleming; Keoshgerian/McClenon; Shelton/Ulrich and Roger Hagie/Frans Vandenbroek, last year’s class winners) were within two laps of each other at the end of the race.

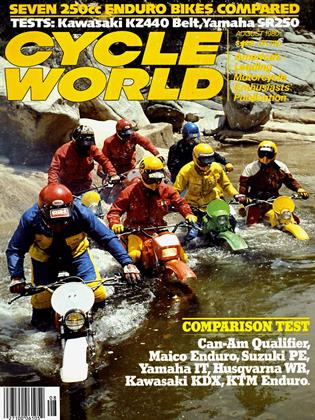

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

August 1980 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1980 -

Departments

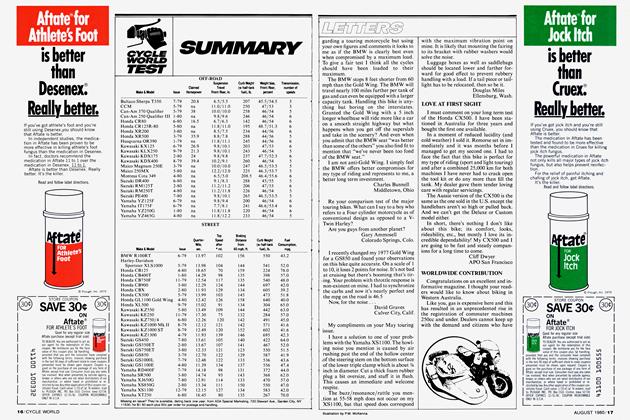

DepartmentsSummary

August 1980 -

Books

BooksAmerican Racer

August 1980 By Henry N. Manney III -

Books

BooksRestoring And Tuning of Classic Motorcycles

August 1980 By Henry N. Manney III -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

August 1980 By Henry N. Manney III