RIDING THE 197 MPH TESON/BERNARD DRAGSTER

It's Power and Sound and Violence

John Ulrich

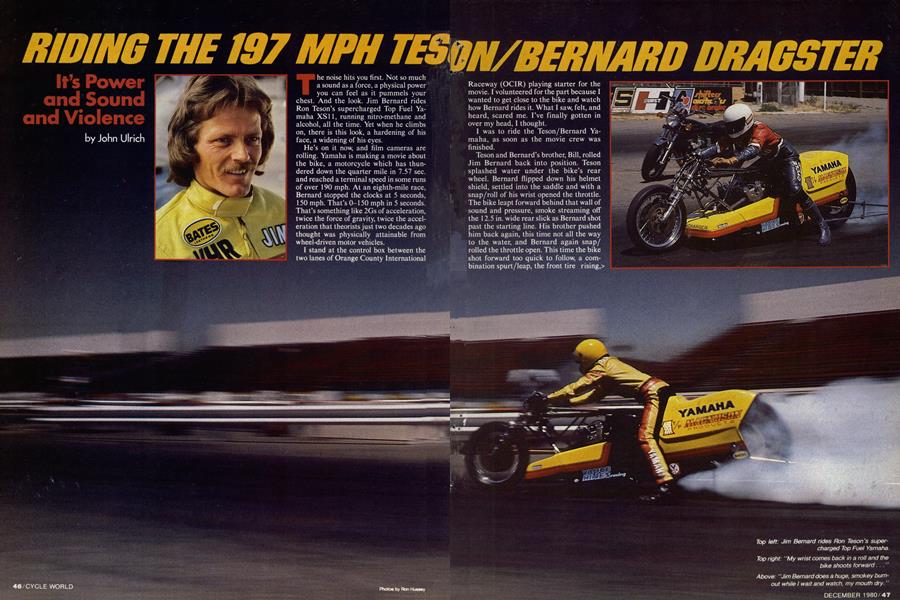

The noise hits you first. Not so much a sound as a force, a physical power you can feel as it pummels your chest. And the look. Jim Bernard rides Ron Teson’s supercharged Top Fuel Yamaha XS11, running nitro-methane and alcohol, all the time. Yet when he climbs on, there is this look, a hardening of his face, a widening of his eyes.

He’s on it now, and film cameras are rolling. Yamaha is making a movie about the bike, a motorcycle which has thundered down the quarter mile in 7.57 sec. and reached a terminal speed in some runs of over 190 mph. At an eighth-mile race, Bernard stopped the clocks at 5 seconds, 150 mph. That’s 0-150 mph in 5 seconds. That’s something like 2Gs of acceleration, twice the force of gravity, twice the acceleration that theorists just two decades ago thought was physically attainable from wheel-driven motor vehicles.

I stand at the control box between the two lanes of Orange County International Raceway (OCIR) playing starter for the movie. I volunteered for the part because I wanted to get close to the bike and watch how Bernard rides it. What I saw, felt, and heard, scared me. I’ve finally gotten in over my head, I thought.

I was to ride the Tesón/Bernard Yamaha, as soon as the movie crew was finished.

Tesón and Bernard’s brother, Bill, rolled Jim Bernard back into position. Tesón splashed water under the bike’s rear wheel. Bernard flipped down his helmet shield, settled into the saddle and with a snap/roll of his wrist opened the throttle.

The bike leapt forward behind that wall of sound and pressure, smoke streaming off the 12.5 in. wide rear slick as Bernard shot past the starting line. His brother pushed him back again, this time not all the way to the water, and Bernard again snap/ rolled the throttle open. This time the bike shot forward too quick to follow, a combination spurt/leap, the front tire rising,> the wheelie bar slamming into the pavement as the slick wrinkled up, gripping against the power. He’s there, then he’s 30 feet forward, the movement looking like a cricket on cocaine. Leap/jump.

How could anybody even know what was happening to him aboard this motorcycle? It happens so quick.

You see words like rocketship, fast, quick, bullet, thunder, all the time in descriptions of fast bikes. But they don’t mean a thing, watching this Yamaha. The trouble with Formula One road racing four-strokes? No power. Too slow.

Modified street bikes? Nothing.

Top fuel motorcycles fit the word violence, mold around it, revel in it, flex their muscles and smile at the sound of the word. Top fuel is violence. Violent sound, violent feel, violent movement. The launch of a Top Fueler is grabbing a child’s doll and shaking it by the head as hard as you can, screaming at the top of your lungs. Shifting into second gear with the throttle wide open is taking that doll and flinging it in front of a runaway gravel truck careening down the Grapevine.

A top fuel bike is violence. You expect that rag doll to be tattered and torn, losing stuffing out the seams.

But the men who ride Top Fuel finish a run, take off their helmet, and return to the pits to get ready for another pass.

The sound.

BURRRRRRURRRRUGHHHH.

Make it deep in your throat, with your cheeks slightly puffed. Make it as loud as you can, warbling it to simulate spots where the rear tire gets egg-shaped from the force and hops or skips over a piece of pavement. Record the sound onto a blank cassette, punch it into your stereo. Turn the volume up all the way, to the maximum, lie six inches in front of the speakers, and turn on the power. Listen.

Then imagine that you’re six feet from a Top Fueler, that the noise is 10 times as loud as the loudest stereo you’ve ever heard. Imagine that the force of the sound against your body pushes you back a step, makes you blink, and when your eyes reopen, that the motorcycle making the noise is . . . gone.

* * *

“It was really scary at the time because I didn’t know what to expect,” Terry Vance told me as he described his first ride on the Suzuki GS 1000 Top Fueler that Byron Hines built him. “The bike’s big and heavy and it kind of goes where it wants to go, and you’re fighting it. The thing is it all happens so fast that if you think that you’re gonna hit something you’ve already hit it, you gotta know where you’re gonna be, not just where you’re at.

“The first time I made a full pass with it,” continued Vance, “it scared the piss out of me, and I only went 8-something, 165 mph. Because when I got to the lights and rolled off the throttle, the front wheel screeched and bike got all weird—it had carried the front wheel all the way through the lights and that just freaked me out. I didn’t even know the front wheel was off the ground until I turned off the throttle.”

* * *

The Teson/Bernard Yamaha weighs 510 lb., produces 350-450 horsepower (“We have no way to tell for sure, but it’s got to be making about that much,” says Tesón). The 12.5 in. wide rear tire, a flattread racing slick with wrinkle-wall sidewalls, is so wide that the bike needs no stand—and will sit upright by itself.

The cylinder head and valves are stock Yamaha, the pistons 1mm oversize (72.5mm) forgings, with a c.r. of 8.5:1. Connecting rods are carved from solid aluminum billet. The crankshaft and crankshaft bearings are stock. A Magnuson supercharger is driven off the crankshaft and feed the engine a mixture of roughly 90 percent nitro-methane and 10 percent alcohol.

The rear of the engine cases (behind the crank) are cut off, an aluminum plate sealing the gap behind the crank. Primary drive is through two straightcut gears into a two-speed transmission and a slipper clutch. Changing gears is accomplished by pushing a big, red button on the left bar, which shifts the transmission by releasing hydraulic pressure.

A Top Fuel pilot’s life is complicated by several things. Consider the throttle. Teson’s bike has a quick throttle moving from closed to fully open in less than onequarter turn. The throttle can never be stationary except at fully closed or fully open. As soon as the rider starts to move the throttle off idle, he must continue to roll the throttle on towards wide open. Pause for an instant part way to full throttle, and the engine mixture leans out, melting the pistons, and, in extreme cases, melting through a piston and burning the top of the connecting rod as well.

Stop part way between closed and open throttle, back it down, and turn it on again before reaching the closed position, and again the pistons melt.

Turn on the throttle too slowly, and the pistons melt. Turn off the throttle too slowly, and the pistons melt.

Turn on the throttle too quickly and the rear tire will either go up in smoke, or else it will elongate so severely (from the combined forces of the traction of very sticky rubber versus the power trying to turn the wheel), that the rear end of the bike will actually hop off the ground. The hopping rear tire leaves a staggered set of burnout marks leading off the starting line, the marks often changing from near rectangles to jagged parallelograms as the bike veers off course and the tire distorts from the rider’s efforts to straighten out.

Getting straightened out is in itself a major problem. Because the rear tire is so wide and so flat, it resists lean—hence the ability of the bike to stand by itself, balanced by the tire. But that means leaning to steer doesn’t work—lean the bike more than a few degrees and the bike runs off the tread area of the slick and onto the corner formed by the junction of the tread rubber and the sidewall. Riding on the sidewall reduces the amount of rubber on the ground, and worse, relocates the center of that rubber patch to one side of the bike’s actual centerline. If that sounds like an engraved invitation to sideways city, that’s because it is.

To turn the bike, the rider must hang his upper body way off to the side he wants to go. If the bike veers left, the rider must hang off to the right. But if he hangs off until the bike is heading right, the bike will go past center and veer right.

“The trick,” says Tesón as he watches Bernard ride the Yamaha, “is to know when to hang off, how much and how long.”

The problem, as anybody watching this all happen can see, is that at the rate of acceleration produced by this Yamaha, the time available for the rider to 1) determine that he is off course and 2) do something about it, isn’t much. As Vance said, it isn’t enough to know where you are, you have to know where you’re going to be.

Ironically, the best and easiest way to get straightened out, according to Bernard, is to accelerate. The faster the bike goes, the easier it is to ride, he tells me.

But obviously, life is a lot simpler if the bike is staged exactly straight and leaves straight, requiring no correction.

“The fast runs, the ones in the sevens, are the easiest,” says Tesón. “It’s those 8.50 runs that are the toughest, because something’s giving you trouble. If everything goes right, the bike leaves straight and runs smooth, and it’s easy.”

Assuming the rider gets off the line in the general direction he wants to go—i.e. straight ahead—and makes it through the timing lights, he’s got to stop. The Tesón/ Bernard Yamaha is fitted with twin discs up front and a single disc on the rear, the left handlebar lever controlling the rear brake and the right handlebar lever controlling the front brakes.

Once through the lights, the rider must roll off the throttle (snap it shut and the bike will shake the front end from the sudden change from accelerating so hard to deceleration), apply the rear brake, then reach down with his left hand and pull a fuel cut-off switch, then wait for the engine rpm to rise (a sign that the engine is leaning out and burning off the residual nitro in the blower). Hitting the kill switch first or too soon after cutting off the fuel will send a backfire through the blower and injector throat, a backfire which can cause tremendous damage to the blower, manifold or engine.

The kill switch itself is a toggle switch mounted near the left grip, inside its own protective “roll cage.” A leather lanyard tied around the ball-end toggle switch has a loop at its other end, that loop fitting around the rider’s wrist. If the rider crashes or his left hand flies off the bars, the lanyard yanks the kill switch, shutting off the engine—and possibly triggering a nitro explosion back through the blower.

I soak up all this information, then watch as Bernard stages for another run. Bernard snaps the throttle on. The bike leaps out and down the track, but by the time my brain comprehends that the bike has gone, Bernard is hanging off, his head, neck and torso cantilevered far to the right of the bike, which is heading left toward the barrier while the rear tire hops, shakes and burns against the track. Bernard wrestles the bike straight and disappears, it all happening in a blink, disaster courted and averted and smothered all the time in the roar and the crush of apocalyptic noise. I walk out onto the track where the bike has traveled, looking at the squares and patches of rubber, marking spots where the fat slick actually touched pavement during one 100-ft. section of the pass.

The rubber marks arc left and back to center, then disappear, replaced by a long unbroken rubber streak fading down towards the lights.

* * *

The bike and Bernard are safely back in the pits. Tesón examines the spark plugs, changes the nitro-laden oil, polluted by the tremendous blowby getting past the piston rings.

“What does it feel like when it’s accelerating its hardest?” I ask Bernard.

“It’s a sensation that you just . . . just . . . can’t describe,” he answers, looking down the track. “It will pin you in the seat and just start tugging on your arms. It’s . . . it’s ... a rush." Bernard pauses, looks up, smiles. “It’s nice.”

I remembered what Terry Vance had told me months earlier, after his inaugural Top Fuel run. I had asked him the same question I asked Bernard—how does it feel. “It’s a feeling you’ll never forget. It makes you want to do it again, that’s for sure. Once you’ve done it, you have to do it again.”

* * *

“After it fires, you make sure it’s in high gear for the burnout,” Bernard tells me as I sit on the bike, before the first pass. Doing a burnout heats the tire, makes it sticky, improving traction and reducing wheelspin at the start. “You make sure it’s in high gear for the burnout. You hold on the rear brake, and bring up the rpm just a little. Then you release the brake and dial on the throttle. It’s just a slow roll-on for the first half (of throttle travel), then from half throttle on it’s just a sudden dump all the way to wide open, you sock it all the way to the stop. Then once you hit the stop you take it and roll it right back off. And she’s got enough power where she’ll smoke the tire just enough.”

I look from Bernard to the throttle, and he continues the instructions.

“Sometimes the bike will hit a bump and start to go to one side or the other during the burnout, and all you have to do is hang off the opposite way to where it’s going and it’ll steer right back. It’s real easy during the burnout. Sometimes I’ll drag my feet to keep the bike going straight, but if everything is working out I’ll put them on the pegs.

“After the burnout, you pull it back into low and check the boost on the boost gauge. You can look at how much boost the bike has and have an idea on what the bike’s going to run like. If it has a lot of boost, it’ll have a lot horsepower. Then you do the short chops to clean off the tire, and then you pull to the line and get ready to make sure she’s going to go straight down the track.

“Then you just dial ’er on.”

* * *

The instructions are over. I’ve already been towed around the parking lot behind Teson’s GT80 Yamaha pit bike, learning to hang my body off from the strange, spread-legged lay-down riding position. The bike really doesn’t like to change direction, and when Tesón sweeps across the lot in a gentle turn, it’s difficult to follow. But after a half a dozen turns and a mile of towing, I have the feel of what I must do enough to keep the bike’s streamlined fiberglass bodywork from scraping on either side, and to keep off the rear tire’s sidewall edge.

That is, I have enough of a feel to do that in the parking lot, at 40 mph.

* * *

“Am I making a big mistake trying to ride this?” I had asked Bernard earlier that morning.

“Naw,” he replied. “You shouldn’t have any trouble.”

Now, Bernard has stepped back. Quiet rings in my ears, stuffed with foam plugs. I wait for Tesón to hook the starter into the > side of the engine, and I stare down the track at the cones marking the timing lights. They seem so tiny, so far away.

Tesón plugs in the starter, spinning over the engine, then motions me to switch on the ignition and gently, barely nudge the throttle.

The engine fires in its open-pipe nitroburning staccato. Bernard stands in front of me, to my right, and signals me to bring up the rpm, slowly, evenly, easy. I concentrate so hard on bringing up the rpm very slowly that it takes me a second to realize Bernard is signalling I’ve got enough rpm and should release the brake and roll on the throttle.

My wrist comes back in a roll and BURRRRRRURRRRGH the bike shoots forward, heading left while I drag my feet and try to turn and hang off right and stare at the Armco barrier getting closer and closer and I’m gonna crash already and then I remember that those levers work the brakes and grab a bunch of both and stop. Bill Bernard is right there, instantly, grabbing the fork tubes and pushing me backwards, expertly steering so all I have to do is lift my feet off the ground and glide back into position for a short chop. Again, slow, slow—but not too slow, not piston-burning slow—roll on and BURRURRRURRUGH and off the throttle faster this time, straighter, traveling a shorter distance and getting on the brakes at once.

I’m staged. The Christmas tree blinks yellow-yellow-green and Bernard is rolling his right hand back at the wrist in a signal for me to go, and I wait and stare and realize that I have to go and that I don’t have the slightest idea what I’m going to do if I get sideways and then I roll the throttle back slowly and suddenly BURRRRRURRRRURRRRGH and the bike moves away from the start mercifully nottoo-quick and I roll it on faster in fear for the lives of the pistons and it’s accelerating and I’m hanging off the right to get straight and when I’m going straight I get the throttle to the stops and punch the button for second gear and BURRRRRRURRRRRURRRRRGH the envelope of sound encases me and I’m jammed back into the seat and my arms are tugged and everything blurs, the only thing I can see at all, the only thing I can focus on is that little group of pylons at the end of the strip and they’re rushing at me and the grandstands and telephone poles all turn into streaks just like the stars do when the spaceships in Star Wars jump into hyperdrive and nothing exists in my peripheral vision and I’m not moving but the track is narrowing to five feet wide and the earth ahead is rushing to meet me, I’m stationary and the earth’s rotation is hurtling towards me and when the telephone poles streaks are 100 feet wide I can’t stand it, my brain can’t understand or comprehend or cope and I roll off the throttle in fear.

In fear.

My left hand finds the rear brake lever and pulls, I coast through the lights, reach down for the fuel shut off lever and coast and coast so far, so close to the ground, and when the rpm starts to rise from leaning out I yank the lanyard on my left wrist and the engine shuts off, followed by a loud POP! from the blower.

I turned off the ignition too soon after hitting the fuel shut off and wonder if the bike is blown up, still coasting, coasting, finally stopping with the brakes and sitting up, slowly.

My right leg is hopping, making my right heel tap dance on the pavement, and I can’t stop it. I look at my dancing leg, twitching like the leg of a grasshopper severed by a lawnmower, and look up again to see Bill Bernard’s face close to my visor. He puts his hand over my heart and pauses.

“Yep. It’s beating,” he says.

And Jim Bernard rides down on the mini and offers to ride the fueler as Bill Bernard tows it back, and I gratefully climb onto Bill’s GS 1000 street bike and ride back to the pits.

By the time I arrive at the pits I’m calm and wondering about what I’ve just done, and the whole thing seems anticlimactic.

Tesón tells me I coasted through the lights at 120 mph, and I think, “Jeez, nothing was streaking when I went through the lights, so I wonder how fast I was going before I shut it off.”

And Tesón asks, “Do you want to make another pass? We’ve got about 15 min. before the far end of the track is closed for the police school.”

I nod and he changes the oil again, checks the plugs, and holds one up to me, pointing out tiny specks of aluminum. “See what I mean about rolling the throttle on and not holding it?” he asks. “You got away with it this time, but you didn’t roll the throttle on fast enough at the start. Do it again and it’s liable to melt the pistons.”

“I don’t want to do a burnout this time” I tell Tesón and the Bernards. “The short chops are okay, but I didn’t like the way I went so far left after the burnout.”

“Well, you have to heat up the tire, or else it’ll just spin at the start and you’ll really have problems,” says Tesón. “Jimmy can do a burnout for you, it’s no problem.”

So Jim Bernard dons his helmet and starts the bike and does a huge, smokey burnout while I wait and watch, my mouth dry.

Bill Bernard pushes him back behind the starting line and Jim Bernard climbs off, handing the bike over to me. I stretch and sit, spreading my legs back to the pegs, reaching for the bars, snapping my shield. Bill Bernard punches the red button into the low gear position and I do a short burnout, BURRRRURRUGH.

Bill Bernard backs me into position, Jim Bernard sights down the bike and Bill helps me make small adjustments so I’ll head straight this time, not to the left.

I’m on the line again, and I really want to go fast. I won’t have another chance— Bernard has races coming up and renting the track for fuel-burning machines is too expensive to do very often. The police school will be practicing pursuit driving at the far end of the strip as soon as I finish this pass. It’s now or never, and I roll on the throttle, faster than before, a lot faster . .. and . . . BURRRRRRURRRRUGH . . .

* * *

From a tape recording made on the scene immediately following my second pass, Jim Bernard speaking:

“She left really good, the slow roll you had was perfect. You started to leave, and got out on the power a little bit and that’s when she started to lean over on the righthand side of the tire. She smoked the tire, and that’s when she got a little crooked with you, that’s when you felt the front end go back and forth, and that’s when you clicked ’er off and got ’er straight. You dialed ’er back on and then she started to move. It looked good. If it would have gone straight, it would have gone fast. I figure at least in the eights, a 160 terminal, at least. She was running on that pass, she really was.”

Bill Bernard, describing the same launch: “It left good. It looked like you needed to counterweight yourself when the bike started to move to the right and were still in the middle instead of leaning to one side to keep it straight. That’s when it rocked over on the side and got up on the tire, and that’s when it smoked the tire. Then you back-peddled it and it started to go right after that. When you plugged it into second gear, it charged in the middle, it started to move.”

♦ * *

By the time the bike was straight again and coasting after getting sideways a hundred feet off the start, I knew my chance at a fast pass was blown. There wouldn’t be another run, but the engine was idling and the Yamaha was headed in the right direction, so I punched into second and rolled it on. BURRRRRURRRRRUGHHHHH and the feeling I started to perceive on the first run returned, stationary objects became fluid as they streaked past, and only the cones stood still on the horizon.

Star Wars. Hyper drive. Worlds and stars turned into horizontal streaks disappearing at your ears.

Tunnel vision. One small scene at the end of a tube of blurr.

Force.

Sound.

Power.

This time, I let the revs rise high enough before hitting the ignition switch. The bike died without a pop. And coasted.

I stopped, and before Bill Bernard arrived, looked at my right leg.

It was still. IS