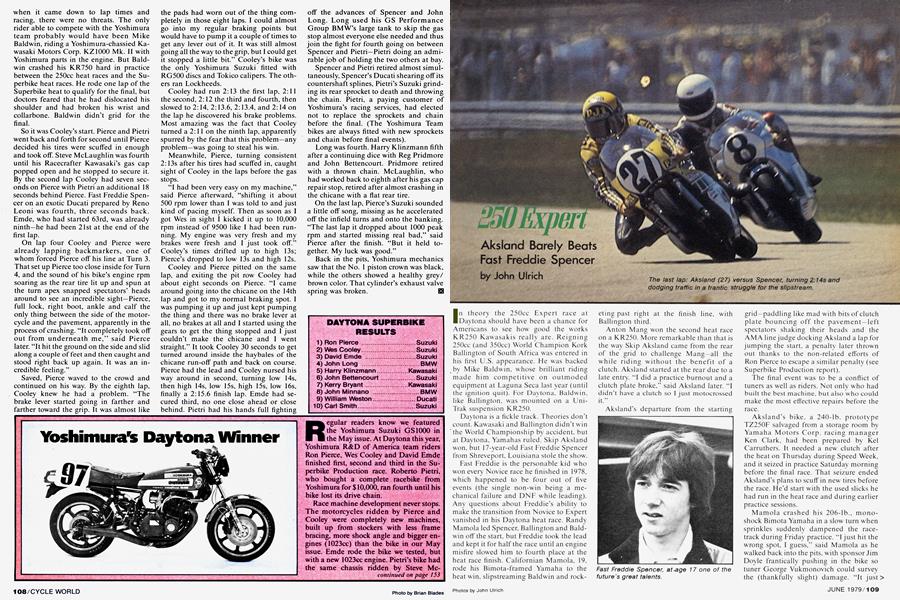

250 Expert

Aksland Barely Beats Fast Freddie Spencer

John Ulrich

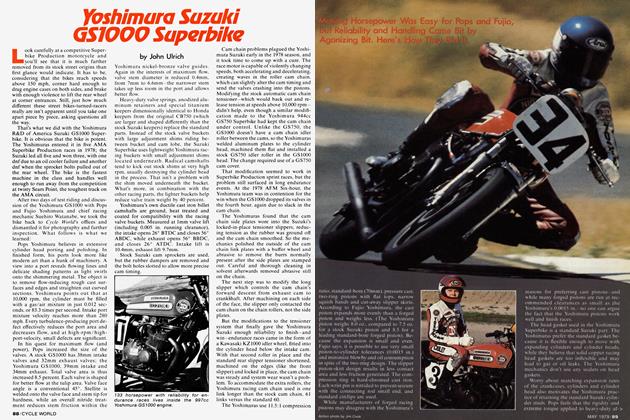

In theory the 250cc Expert race at Daytona should have been a chance for Americans to see how good the works KR250 Kawasakis really are. Reigning 250cc (and 350cc) World Champion Kork Ballington of South Africa was entered in his first U.S. appearance. He was backed by Mike Baldwin, whose brilliant riding made him competitive on outmoded equipment at Laguna Seca last year (until the ignition quit). For Daytona, Baldwin, like Ballington, was mounted on a Uni-Trak suspension KR250.

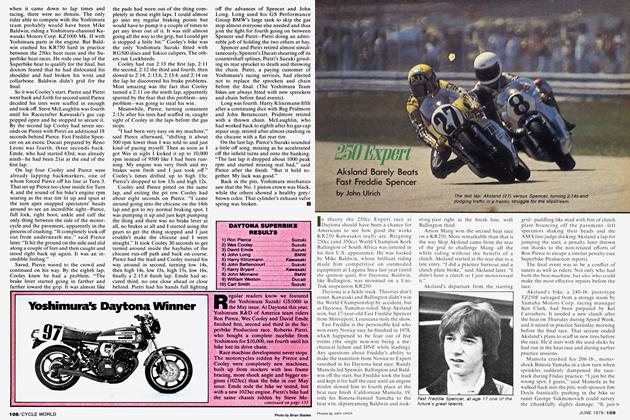

Daytona is a fickle track. Theories don’t count. Kaw'asaki and Ballington didn’t win the World Championship by accident, but at Daytona, Yamahas ruled. Skip Aksland won, but 17-year-old Fast Freddie Spencer from Shreveport, Louisiana stole the show.

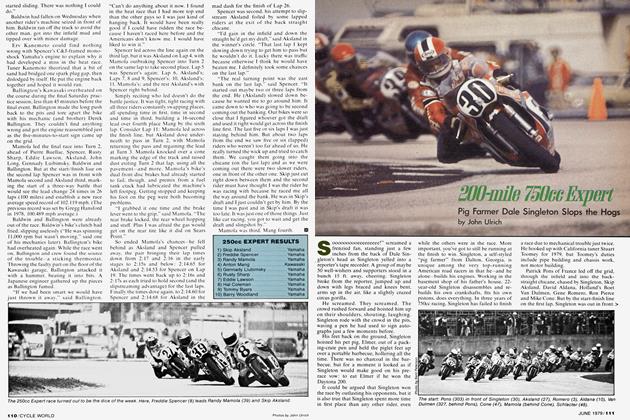

Last Lreddie is the personable kid who won every Novice race he finished in 1978, which happened to be four out of five events (the single non-win being a mechanical failure and DNL while leading). Any questions about Lreddie’s ability to make the transition from Novice to Expert vanished in his Daytona heat race. Randy Mamola led Spencer, Ballington and Baldwin off the start, but Lreddie took the lead and kept it for half the race until an engine misfire slowed him to fourth place at the heat race finish. Californian Mamola, 19, rode his Bimota-framed Yamaha to the heat win, slipstreaming Baldw in and rocketing past right at the finish line, with Ballington third.

Anton Mang won the second heat race on a KR250. More remarkable than that is the way Skip Aksland came from the rear of the grid to challenge Mang—all the while riding without the benefit of a clutch. Aksland started at the rear due to a late entry. “I did a practice burnout and a clutch plate broke,” said Aksland later. ‘T didn’t have a clutch so I just motocrossed it.”

Aksland’s departure from the starting grid—paddling like mad with bits of clutch plate bouncing off the pavement—left spectators shaking their heads and the AMA line judge docking Aksland a lap for jumping the start, a penalty later thrown out thanks to the non-related efforts of Ron Pierce to escape a similar penalty (see Superbike Production report).

The final event was to be a conflict of tuners as well as riders. Not only who had built the best machine, but also who could make the most effective repairs before the race.

Aksland’s bike, a 240-lb. prototype TZ250L salvaged from a storage room by Yamaha Motors Corp. racing manager Ken Clark, had been prepared by Kel Carruthers. It needed a new clutch after the heat on Thursday during Speed Week, and it seized in practice Saturday morning before the final race. That seizure ended Aksland’s plans to scuff in new tires before the race. He’d start with the used slicks he had run in the heat race and during earlier practice sessions.

Mamola crashed his 206-lb., monoshock Bimota Yamaha in a slow turn when sprinkles suddenly dampened the racetrack during Lriday practice. “I just hit the wrong spot, I guess,” said Mamola as he walked back into the pits, with sponsor Jim Doyle frantically pushing in the bike so tuner George Vukmonovich could survey the (thankfully slight) damage. “It just> started sliding. There was nothing I could do.”

Baldwin had fallen on Wednesday when another rider’s machine seized in front of him. Baldw in ran off the track to avoid the other man, got into the infield mud and tipped over with minor damage.

Erv Kanemoto could find nothing wrong with Spencer's C&J-framed monoshock Yamaha’s engine to explain why it had developed a miss in the heat race. Tuner Kanemoto theorized that a bit of sand had bridged one spark plug gap, then dislodged by itself. He put the engine back together and hoped it would run.

Ballington’s Kawasaki overheated on the course during the final Saturday practice session, less than 45 minutes before the final event. Ballington made the long push back to the pits and tore apart the bike w'ith his mechanic (and brother) Derek Ballington. They couldn't find anything w rong and got the engine reassembled just as the five-minutes-to-start sign came up on the grid.

Mamola led the final race into Turn 2, ahead of Pierre Buellac. Spencer, Rusty Sharp, Eddie Lawson, Aksland, John Long, Gennady Luibimsky, Baldwin and Ballington. But at the start/finish line on the second lap Spencer was in front with Mamola second and Aksland third, marking the start of a three-way battle that would see the lead change 24 times in 26 laps (100 miles) and establish a new race average speed record of 102.119 mph. (The previous record was set by Gregg Hansford in 1978, 100.489 mph average.)

Baldwin and Ballington were already out of the race. Baldw in’s bike's clutch had fried, slipping uselessly (“He was spinning 11.000 rpm but wasn't moving,” said one of his mechanics later). Ballington’s bike had overheated again. While the race went on, Ballington and crew found the source of the trouble —a sticking thermostat. Throwing the faulty part on the floor of the Kawasaki garage, Ballington attacked it with a hammer, beating it into bits. A Japanese engineer gathered up the pieces as Ballington fumed.

“If we had been smart we would have just thrown it away.” said Ballington. “Can’t do anything about it now'. I found in the heat race that I had more top end than the other guys so I was just kind of hanging back. It would have been really good if I could have ridden the race because I haven’t raced here before and the Americans don't know me. I would have liked to win it.”

Spencer led across the line again on the third lap. but it was Aksland on Lap 4. with Mamola outbraking Spencer into Turn 2 on the same lap to take second place. Lap 5 was Spencer’s again: Lap 6, Aksland's; Laps 7. 8 and 9. Spencer’s; 10. Aksland's:

11. Mamola’s; and the rest Aksland’s with Spencer right behind.

Simply reciting who led doesn’t do the battle justice. It was tight, tight racing w ith all three riders constantly swapping places, all spending time in first, time in second and time in third, building a 16-second lead over fourth place Mang by the sixth lap. Consider Lap 1 1: Mamola led across the finish line, but Aksland dove underneath to pass in Turn 2, with Mamola returning the pass and regaining the lead at Turn 3. Mamola knocked over a cone marking the edge of the track and raised dust exiting Turn 2 that lap, using all the pavement—and more. Mamola’s bike's dual front disc brakes had already started to fail, though, and premix from a fuel tank crack had lubricated the machine's left footpeg. Getting stopped and keeping his foot on the peg were both becoming problems.

“1 grabbed it one time and the brake lever went to the grip.” said Mamola. “The rear brake locked, the rear wheel hopping and stuff. Plus I was afraid the gas would get on the rear tire like it did on Sears Point.”

So ended Mamola’s chances—he fell behind as Aksland and Spencer pulled away, the pair bringing their lap times down from 2:17 and 2:16 in the early stages to 2:15s and below: 2:14.65 for Aksland and 2:14.53 for Spencer on Lap 19. The times went back up to 2:16s and 2:17s as each tried to hold second (and the slipstreaming advantage) for the last laps. Linally the times dove again, to 2:14.60 for Spencer and 2:14.68 for Aksland in the mad dash for the finish of Lap 26.

Spencer was second, his attempt to slipstream Aksland foiled by some lapped riders at the exit of the back straight chicane.

“I'd gain in the infield and down the straight he’d get my draft,” said Aksland in the winner's circle. “That last lap I kept slowing down trying to get him to pass but he wouldn’t do it. Lucky there was traffic because otherwise I think he would have beaten me. I definitely took some chances on the last lap.”

“The real turning point was the east bank on the last lap,” said Spencer. “It started out maybe two or three laps from the end. He (Äksland) slowed down because he wanted me to go around him. It came down to who was going to be second coming out the banking. Our bikes were so close that I figured whoever got the draft and used it right would get across the finish line first. The last five or six laps I was just staying behind him. But about two laps from the end we saw five or six (lapped) riders who weren't too far ahead of us. He really turned the wick up and tried to catch them. We caught them going into the chicane (on the last lap) and as we were coming out there were two slower riders, one in front of the other one. Skip just cut right down between them and the second rider must have thought I was the rider he was racing with because he raced me all the way around the bank. He was in Skip’s draft and I just couldn’t get by him. By the time I was past and in Skip's draft it was too late. It wasjust one of those things. Just like car racing, you got to wait and get the draft and slingshot by.”

Mamola was third. Mang fourth. 3

250cc EXPERT RESULTS