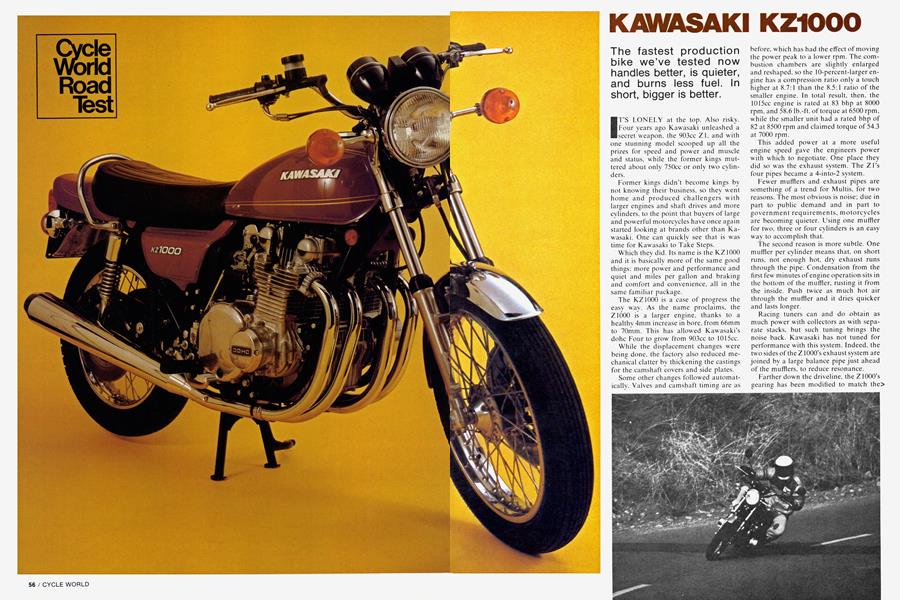

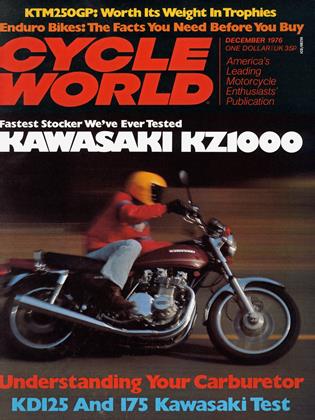

Cycle World Road Test

KAWASAKI KZ1000

The fastest production bike we’ve tested now handles better, is quieter, and burns less fuel. In short, bigger is better.

IT’S LONELY at the top. Also risky. Four years ago Kawasaki unleashed a secret weapon, the 903cc Z1, and with one stunning model scooped up all the prizes for speed and power and muscle and status, while the former kings muttered about only 750cc or only two cylinders.

Former kings didn’t become kings by not knowing their business, so they went home and produced challengers with larger engines and shaft drives and more cylinders, to the point that buyers of large and powerful motorcycles have once again started looking at brands other than Kawasaki. One can quickly see that is was time for Kawasaki to Take Steps.

Which they did. Its name is the KZIOOO and it is basically more of the same good things: more power and performance and quiet and miles per gallon and braking and comfort and convenience, all in the same familiar package.

The KZIOOO is a case of progress the easy way. As the name proclaims, the Z1Ó00 is a larger engine, thanks to a healthy 4mm increase in bore, from 66mm to 70mm. This has allowed Kawasaki’s dohc Four to grow from 903cc to 1015cc.

While the displacement changes were being done, the factory also reduced mechanical clatter by thickening the castings for the camshaft covers and side plates.

Some other changes followed automatically. Valves and camshaft timing are as

before, which has had the effect of moving the power peak to a lower rpm. The combustion chambers are slightly enlarged and reshaped, so the 10-percent-larger engine has a compression ratio only a touch higher at 8.7:1 than the 8.5:1 ratio of the smaller engine. In total result, then, the 1015cc engine is rated at 83 bhp at 8000 rpm. and 58.6 lb.-ft. of torque at 6500 rpm, while the smaller unit had a rated bhp of 82 at 8500 rpm and claimed torque of 54.3 at 7000 rpm.

This added power at a more useful engine speed gave the engineers power with which to negotiate. One place they did so was the exhaust system. The Zl’s four pipes became a 4-into-2 system.

Fewer mufflers and exhaust pipes are something of a trend for Multis, for two reasons. The most obvious is noise: due in part to public demand and in part to government requirements, motorcycles are becoming quieter. Using one muffler for two. three or four cylinders is an easy way to accomplish that.

The second reason is more subtle. One muffler per cylinder means that, on short runs, not enough hot, dry exhaust runs through the pipe. Condensation from the first few minutes of engine operation sits in the bottom of the muffler, rusting it from the inside. Push twice as much hot air through the muffler and it dries quicker and lasts longer.

Racing tuners can and do obtain as much power with collectors as with separate stacks, but such tuning brings the noise back. Kawasaki has not tuned for performance with this system. Indeed, the two sides of the Z1000’s exhaust system are joined by a large balance pipe just ahead of the mufflers, to reduce resonance.

Farther down the driveline, the Z 1000's gearing has been modified to match the> added pow-er at low-er engine speed. The rear sprocket carries tw-o fewer teeth, so the larger engine is turning more slowly for any given road speed. (Primary reduction and internal ratios of the five-speed transmission are unchanged).

There is a nice benefit from the newfinal drive ratio. A large engine running slowly with a large throttle opening is more efficient at cruising speeds than is a smaller engine running faster with less throttle opening. Reason is. that the engine isn’t using pow-er pulling against its own closed throttles. For that reason, the larger, more powerful, slow-er-turning KZ1000 returned an average of 52 mpg during the test. Earlier Z Is varied from 44 mpg on a fast run to 57 at easy cruising, so it’s safe to say the bigger motor does as much work with more efficiency. Nice to say these days.

Another major engineering change for the Z1000 is perhaps obvious and overdue: a rear disc brake, basically the same unit fitted earlier to the KZ750 and the 1976 LTD Zl.

The brake itself is a good unit. Because the Z 1000 has all that speed potential, the best possible brakes are none too good. And with other things being equal, a disc brake provides better braking control and longevity than a drum brake.

At the same time, a motorcycle’s front brake does virtually all of the heavy work. The Z1000 in theory w-ould benefit more from a dual front disc than from disc brakes at each end. Dual front units are. in fact, fitted to the Zl and Z1000 sold in Europe, w here, alas, they are allow-ed to go faster than we are. Kaw-asaki could easily have gone to a double-disc front, rear drum system with parts already in production.

Function comes in many forms. There are certain pieces of equipment now being fitted because the customers like and expect them. Disc brakes head this list. The outsider’s guess must be that the rear disc is a stronger selling point than tw-o front discs would be. so the factory fitted the rear disc.

A subtle change for the Z1000 involves the frame and/or the brakes. When the European version of the Zl went to dualdisc brakes in front, the factory provided a larger and stronger gusset bracing the downtubes just belowthe steering head, on the logical premise that the frame, never know n for being stiff, nowhad more force to resist. Kawasaki provided the same new gusset for the limited-production LTD Z1 sold in the U.S. last year and for the Z1000 now-. A good thing.

More work has gone into sound control. The Z1000 has a newairbox with two snorkel-type intakes, shaped to reduce intake roar to a mild hum.

The other changes in the conversion from Zl to Z1000 are mostly minor. The passenger footpegs have new brackets and are a bit closer to the ground, the wires for the switches and controls are routed inside the handlebars, the reminder buzzer has been removed from the turn signals, items like that.

Side note: The factory men here say Kawasaki has its own self-canceling system. but hasn’t put it into production because the home office isn’t convinced it’s a selling point w-orth the extra money. Perhaps nowthat Yamaha is getting raves for its system, the other makers will fall into line.

The Z1000 naturally looks like the Zl, even to the extent that the ducktail top , chromed bottom rear fender appears out of date. Colors for 1977 are maroon, as on the test bike, and an equally pleasant dark green.

Kawasaki’s big Four is famous for performance. so the first thing to be said about the larger motor is simply that it is quick.

Spell that QUICK.

The KZ1000 did the standing quarter mile in 12.19 sec. with a trap speed of 107.65 mph.

For logical comparisons, the Zl had an e.t. of 12.7 sec., the Honda CB750F did 13.52. the BMW R90/6 did 13.22, the Yamaha XD750 Triple did 13.99, and the Honda GLIOOO’s best is 13.14.

The KZ1000 is the quickest production bike w-e’ve tested, and it’s still King of the Superbikes.

Top speed w-as an honest 120 at the end of a half-mile run, exactly w-hat the Z1 did in 1975. proving that the gearing is exactly right.

Wow-. More acceleration, more miles per gallon and equal top speed, all at a noise level so lowone almost looks for a long extension cord.

Criticism? Yeah. The good runs came early, then the clutch heated up and lost its competitive grip. The 903cc engine was> good for hard runs all day, so we’d guess the larger engine is fitted with the original clutch, which may not be up to the demands of competition.

The chassis and handling news is that the KZ1000 does, in fact, have the improved stiifness and stability the extra bracing would lead us to predict. The Z1000 runs straight and can be pitched into turns at sporting speed without the handling going all funny, that is, not at all funny.

The suspension is mostly as it was. Constant readers will correctly infer that the initial damping and springing are too stiff, giving a harsh ride at both ends overjumps and ridges. With the wick up, the Z1000 becomes more of a handful, as the damping in the rear shocks mismatches with the stiff springs. Bumps in a turn produce a pogo effect: The rear wheel squats and the rear of the frame comes up harder than it went down, changing the steering response and making the rider nervous. All this can be felt well before actual pitch-off time, so the Z1000 isn’t dangerous or unstable. It’s a large Kawasaki, is all.

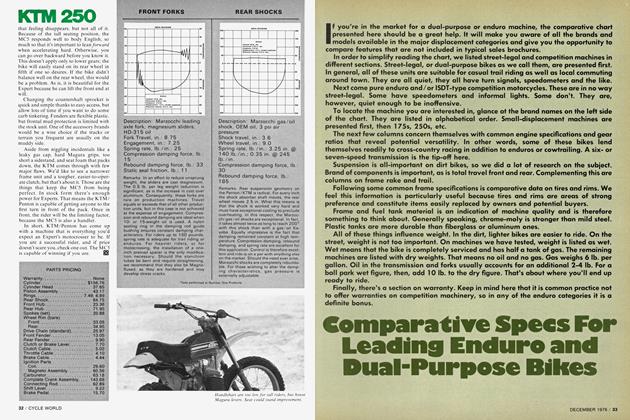

FRONT FORKS

Description: KZ1000 Kayaba fork, HD-315 oil Fork travel, in.: 5.0 Engagement, in.: 6.7 Spring rate, lb./in.: 55 Compression damping, lb.: 9 Rebound damping force, lb.: 35 Static seal friction, lb.: 10 Remarks: One of the biggest changes on the KZ1000 is additional frame gusseting. To take advantage of the increased handling potential, Kawasaki has increased the spring rate slightly from 38/45 progressive to 55 lb. Over big bumps, this means a harsher ride than before. Overall, however, ride has been improved by reductions in both static seal drag and compression damping. Static seal drag is half of what it was before. Compression damping has been reduced from 15 to 9 lb. Rebound damping at 35 lb. has not been changed. Touring riders can obtain a nicer ride by going to a set of softer fork springs, available from either S&W or Number One Products. Tests performed at Number One Products

REAR SHOCKS

Description: KZ1000 air/oil shock, non-rebuildable Shock travel, in.: 2.8 Wheel travel, in.: 3.7 Spring rate, lb./in.: 129/157 progressive Compression damping, lb.: 18 Rebound damping, lb.: 140 Remarks: The rear shock remains essentially the same. Compression damping is identical at 18 lb. This is high for road riding and contributes to the KZIOOO’s firm ride. Rebound damping is slightly less, and is an excellent match for the spring. The spring itself is now a progressive wind, and the initial rate is slightly higher: 129 lb. vs. 120. What all this means is that it takes less force than the KZ900 required to move the KZ1000 wheel the first inch. The second inch of wheel travel requires about the same force on both bikes. At the three-inch mark, the progressive spring on the KZ1000 comes into play. The new spring, then, allows a softer, initial ride than on the 900 series without increasing the possibility of bottoming.

Ground clearance is better than adequate. Fierce effort drew sparks from the centerstand on hard left sweepers, no grounding at all from the right-hand side. This is academic, as the speed required to ground the bike is racing speed. An owner who gets this far over on the highway would likely scrape himself off doing some other dumb thing even if the Z didn’t touch down.

A slightly unexpected handling note is that the Z1000 feels lighter and more responsive at low speeds. The early models tended to tip in on slow turns, and the test Z1000 doesn’t. Suspension setting, dimensions, center of gravity, etc., are unchanged, far as we can measure and far as the factory’s manual shows. One guess is that the steering head area was far less rigid than even the designers suspected, but that’s a guess at best; and anyway, if the bike feels better at low speed, the reason why isn’t too important.

In daily use, the KZ1000 is a good, big motorcycle, with the virtues and flaws normal to its size and type. The engine fires on the first or second spin, hot or cold, and the bike can be ridden away almost immediately, although a touch of choke is needed for the first mile or so.

On the one hand, the lOOOcc engine has lots of torque. Staying with the earlier camshafts and the smaller carburetors introduced for the 1976 model year has widened the powerband and moved it lower on the rpm scale. Crack the throttle and there’s enough power to move off the mark and up through the gears. The engine will pull smoothly from 2500 rpm in fifth gear—not strongly, mind—but if you wish to investigate the engine’s flexibility, the engine will do it.

At freeway speeds, a steady 55 mph or so, the loudest noise is the tires. Honest. The engine makes a faint hum, with intake and exhaust and gears so quiet it’s nearly impossible to distinguish one from the other. The engine begins to make power at 4000 rpm or so, which matches the legal maximum nicely. Passing with power on in top is damned quick. Naturally, dropping down one or two gears brings all the flaming great leaps forward a highway rider can handle, perhaps more, as 75, 80 and above come faster than the rider can watch the dials. Performance is no problem.

On the other hand, at low road and engine speeds, the KZ1000 feels heavy. The primary drive gears scream at less than 4000 rpm, or perhaps we hear them now because we no longer hear the exhaust pipes. The Z transmission clunked when it was introduced and still does. Smoothly working clutch and gearshift at low speeds requires practice and attention. The impression when trickling around town is that the mild engine is effected more by the flywheel than it should be. The result is a tendency to lurch through the gears.

This carries over to neutral, which can be elusive. At rest, no problem. Nudge the lever and neutral arrives. When rolling, though, the rider tends to slide from second to first and back to second and back to first, groping for neutral while the hefty transmission gears use their own inertia against the rider’s will. Sure, there could be worse things to worry about.

In terms of actual measured performance, the all-disc brakes are excellent. They do require practice. The rear brake lever is all but unchanged from the old drum unit, and while leverage surely was worked out beforehand via the rear caliper, the more powerful rear brake makes itself known first by not requiring much foot force. The front brake, meanwhile, demands a firm hand. Separate control of front and rear is, of course, a normal motorcycle practice, and one to which the rider becomes accustomed. Even so, the KZ1000 requires less foot force and more hand force than average, and the newcomer tends to overuse the rear brake while learning this. Luckily, the Dunlop K87 rear tire squeals at the slightest provocation, so there’s an early warning system at work well before the rear wheel actually locks or sends the bike into terminal gyrations.

(Continued on page 86)

KAWASAKI

KZ1000

$2575

Continued from page 61

The KZ1000 has some interesting ergnomics. The turn signal switches are of the plain on-and-off variety, i.e., the rider must turn them off for himself. The headlights are also subject to human control. Yet the electric starter is wired through an interlock that prevents the starter from working unless the clutch lever is pulled in, even when the transmission is in neutral, a safety device that denies the operator’s ability.

Perhaps someday “Darwinism and the Motorcycle” will be the title of a definitive essay determining whether every step toward making bikes idiot-proof also moves bikers one step toward becoming idiots.

Meanwhile, and thank goodness, the important controls of the KZ 1000 are well done, as they were on the Zl. The positions for head, feet and hands are fine for the rider of average height and weight, the bend of the bars matches the average wrist, and the foot controls are positioned to suit the pegs. The passenger pegs are about one inch farther back from the rider pegs, and our two-up passengers said they worked quite well.

The seat was remarkable in that it occasioned no remarks. The first impression was of slickness, but that turned out to be a matter of the ZlOOO’s incredible power scooting the machine out from under. The padding isn’t especially soft, nor especially hard. At the end of hours in the saddle, the rider still hasn’t noticed the seat, which may be the highest compliment one can offer.

What we have with the Kawasaki KZ1000 is the good of Zl with improvements large and small. In sum, the KZ 1000 is a better motorcycle. JÔJ

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound·up

December 1976 -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1976 -

Demise of the British Industry, Ii

December 1976 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

December 1976 -

Technical

TechnicalComparative Specs For Leading Enduro And Dual-Purpose Bikes

December 1976 -

Features

FeaturesPro Techniques For Off-Road Riding

December 1976 By Russ Darnell