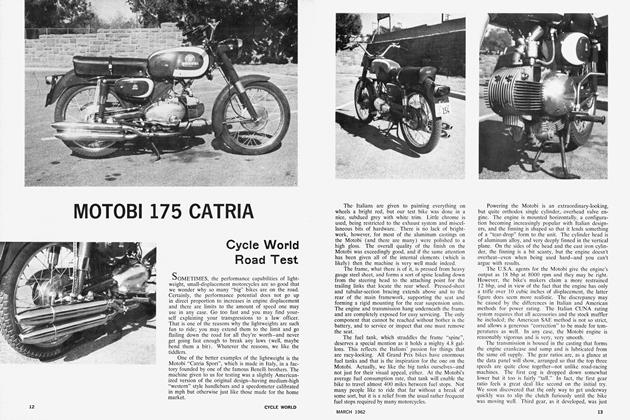

COTTON COUGAR

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

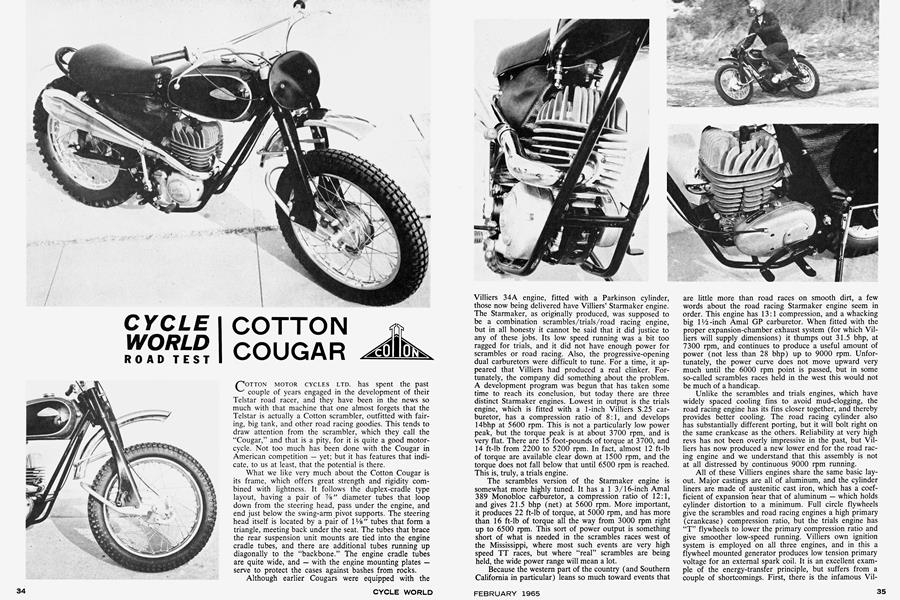

COTTON MOTOR CYCLES LTD. has spent the past couple of years engaged in the development of their Telstar road racer, and they have been in the news so much with that machine that one almost forgets that the Telstar is actually a Cotton scrambler, outfitted with fairing, big tank, and other road racing goodies. This tends to draw attention from the scrambler, which they call the “Cougar,” and that is a pity, for it is quite a good motorcycle. Not too much has been done with the Cougar in American competition — yet; but it has features that indicate, to us at least, that the potential is there.

What we like very much about the Cotton Cougar is its frame, which offers great strength and rigidity combined with lightness. It follows the duplex-cradle type layout, having a pair of ⅞" diameter tubes that loop down from the steering head, pass under the engine, and end just below the swing-arm pivot supports. The steering head itself is located by a pair of 1⅛" tubes that form a triangle, meeting back under the seat. The tubes that brace the rear suspension unit mounts are tied into the engine cradle tubes, and there are additional tubes running up diagonally to the “backbone.” The engine cradle tubes are quite wide, and — with the engine mounting plates — serve to protect the cases against bashes from rocks.

Although earlier Cougars were equipped with the Villiers 34A engine, fitted with a Parkinson cylinder, those now being delivered have Villiers’ Starmaker engine. The Starmaker, as originally produced, was supposed to be a combination scrambles/trials/road racing engine, but in all honesty it cannot be said that it did justice to any of these jobs. Its low speed running was a bit too ragged for trials, and it did not have enough power for scrambles or road racing. Also, the progressive-opening dual carburetors were difficult to tune. For a time, it appeared that Villiers had produced a real clinker. Fortunately, the company did something about the problem. A development program was begun that has taken some time to reach its conclusion, but today there are three distinct Starmaker engines. Lowest in output is the trials engine, which is fitted with a 1-inch Villiers S.25 carburetor, has a compression ratio of 8:1, and develops 14bhp at 5600 rpm. This is not a particularly low power peak, but the torque peak is at about 3700 rpm, and is very flat. There are 15 foot-pounds of torque at 3700, and 14 ft-lb from 2200 to 5200 rpm. In fact, almost 12 ft-lb of torque are available clear down at 1500 rpm, and the torque does not fall below that until 6500 rpm is reached. This is, truly, a trials engine.

The scrambles version of the Starmaker engine is somewhat more highly tuned. It has a 1 3/16-inch Amal 389 Monobloc carburetor, a compression ratio of 12:1, and gives 21.5 bhp (net) at 5600 rpm. More important, it produces 22 ft-lb of torque, at 5000 rpm, and has more than 16 ft-lb of torque all the way from 3000 rpm right up to 6500 rpm. This sort of power output is something short of what is needed in the scrambles races west of the Mississippi, where most such events are very high speed TT races, but where “real” scrambles are being held, the wide power range will mean a lot.

Because the western part of the country (and Southern California in particular) leans so much toward events that are little more than road races on smooth dirt, a few words about the road racing Starmaker engine seem in order. This engine has 13:1 compression, and a whacking big 1 Vi-inch Amal GP carburetor. When fitted with the proper expansion-chamber exhaust system (for which Villiers will supply dimensions) it thumps out 31.5 bhp, at 7300 rpm, and continues to produce a useful amount of power (not less than 28 bhp) up to 9000 rpm. Unfortunately, the power curve does not move upward very much until the 6000 rpm point is passed, but in some so-called scrambles races held in the west this would not be much of a handicap.

Unlike the scrambles and trials engines, which have widely spaced cooling fins to avoid mud-clogging, the road racing engine has its fins closer together, and thereby provides better cooling. The road racing cylinder also has substantially different porting, but it will bolt right on the same crankcase as the others. Reliability at very high revs has not been overly impressive in the past, but Villiers has now produced a new lower end for the road racing engine and we understand that this assembly is not at all distressed by continuous 9000 rpm running.

All of these Villiers engines share the same basic layout. Major castings are all of aluminum, and the cylinder liners are made of austenitic cast iron, which has a coefficient of expansion hear that of aluminum — which holds cylinder distortion to a minimum. Full circle flywheels give the scrambles and road racing engines a high primary (crankcase) compression ratio, but the trials engine has “T” flywheels to lower the primary compression ratio and give smoother low-speed running. Villiers own ignition system is employed on all three engines, and in this a flywheel mounted generator produces low tension primary voltage for an external spark coil. It is an excellent example of the energy-transfer principle, but suffers from a couple of shortcomings. First, there is the infamous Villiers coil, which can easily be replaced by something more reliable (we have found that a condenser from a 6-cylinder, 6-volt Chevrolet is just the thing).

The second shortcoming does not exist if you can be content with a 7000 rpm limit. Above that, the inevitable slight flexing of the crankshaft upsets the ignition timing. The ignition system’s breaker cam is out on the “dynamo” end of the crank, and very slight flexing of the crank will cause the nominal center of this cam to start swinging an arc. When this happens, the points no longer break at the proper time. Villiers has cured this problem in the road racing engine by mounting the breaker cam on a shaft carried in a separate set of bearings, and driven from the crankshaft by a flexible coupling. That is a point worth remembering if you start a big hop-up program with your Cotton Cougar.

Quite an unusual clutch is used in the Starmaker power/transmission package. It has bronze and steel plates, and engagement pressure is supplied by a diaphragmspring. This is a plate made of spring steel, slotted from the inside out almost to its edge, and having a shallow conical form. Diaphragm springs exert maximum pressure when almost flat, and relax when pulled back past “center.” Thus, when you squeeze in the clutch lever (assuming linkage is properly adjusted) you pull the spring back past center and the clutch action becomes lighter as the clutch disengages — the exact opposite of a conventional clutch.

This clutch is fitted on a transmission that is very conventional — and very, very good. Early examples produced had some weaknesses, but these have been corrected. Transmissions being made now are reliable — as they should be, with all the shafts running on either ball or needle-roller bearings — and they shift quite smoothly. Internal ratios in the scrambles transmission are 1.00:1; 1.25:1; 1.66:1; and 2.52:1. The primary drive, by duplex .375-pitch chain, has a ratio of 2.15:1.

Previously, Cotton Cougars were imported fitted with a 1.5-gallon fiberglass tank, and this is still available for those that want it, but the importers tell us that their customers’ habit of smashing into rocks and things resulted in a few cracked tanks, so these are now of steel and hold 3 gallons. Chrome-plated steel fenders are still fitted on all Cougars, and while these are not especially light, they are made of material sufficiently thick to reduce the possibility of damage.

The Armstrong leading-link forks on the Cotton Cougar, like all of their kind, make the front end feel a bit ponderous, but there is little of the slow side-to-side oscillating that we have come to associate with the type. And, of course, they do give a long wheel travel that will soak up some remarkable humps in the terrain. On the Cougar, the fork legs are made of very substantial material, and there are flat-plate braces up around the fork bridges, so we do not think that many riders will be able to bend them. •

COTTON

COUGAR

SPECIFICATIONS

$844.00

PERFORMANCE