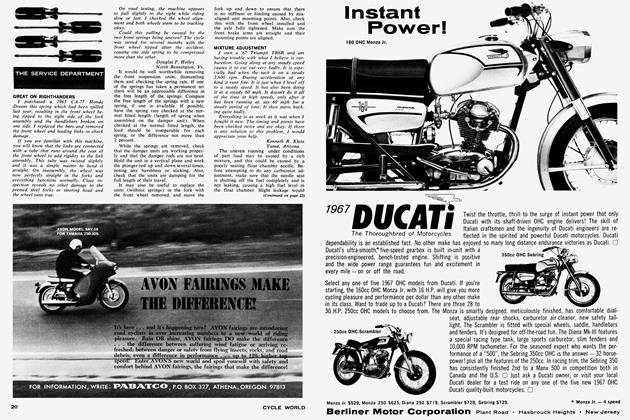

GREEVES 250 RANGER

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

IN OUR TRIALS ISSUE INTERVIEW (CYCLE WORLD, April,

1967), master path-picker Sammy Miller remarked that while a trail bike "would not necessarily make a good trials bike, a trials bike would be an exceptionally good trailer." And we couldn't agree more — particularly after having a go with the Greeves Ranger, a superbly modified — or should we say disguised — version of Greeves' brilliant Anglian trials machine. A general impression we gained from the Ranger was that Bert Greeves took Sammy's remarks to heart, or relied on his own good judgment, or heeded the advice of U. S. Greeves distributor Nick Nicholson, or all three in coming up with the Ranger, because this just has to be one of the best trail motorcycles ever built.

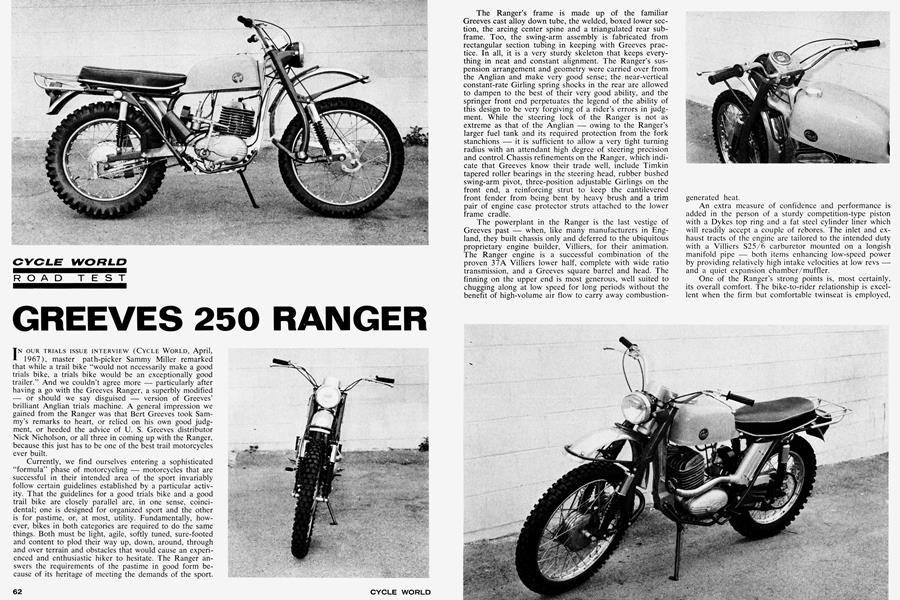

Currently, we find ourselves entering a sophisticated "formula" phase of motorcycling — motorcycles that are successful in their intended area of the sport invariably follow certain guidelines established by a particular activity. That the guidelines for a good trials bike and a good trail bike are closely parallel are, in one sense, coincidental; one is designed for organized sport and the other is for pastime, or, at most, utility. Fundamentally, however, bikes in both categories are required to do the same things. Both must be light, agile, softly tuned, sure-footed and content to plod their way up, down, around, through and over terrain and obstacles that would cause an experienced and enthusiastic hiker to hesitate. The Ranger answers the requirements of the pastime in good form because of its heritage of meeting the demands of the sport. The Ranger's frame is made up of the familiar Greeves cast alloy down tube, the welded, boxed lower section, the arcing center spine and a triangulated rear subframe. Too, the swing-arm assembly is fabricated from rectangular section tubing in keeping with Greeves practice. In all, it is a very sturdy skeleton that keeps everything in neat and constant alignment. The Ranger's suspension arrangement and geometry were carried over from the Anglian and make very good sense; the near-vertical constant-rate Girling spring shocks in the rear are allowed to dampen to the best of their very good ability, and the springer front end perpetuates the legend of the ability of this design to be very forgiving of a rider's errors in judgment. While the steering lock of the Ranger is not as extreme as that of the Anglian — owing to the Ranger's larger fuel tank and its required protection from the fork stanchions — it is sufficient to allow a very tight turning radius with an attendant high degree of steering precision and control. Chassis refinements on the Ranger, which indicate that Greeves know their trade well, include Timkin tapered roller bearings in the steering head, rubber bushed swing-arm pivot, three-position adjustable Girlings on the front end, a reinforcing strut to keep the cantilevered front fender from being bent by heavy brush and a trim pair of engine case protector struts attached to the lower frame cradle.

The powerplant in the Ranger is the last vestige of Greeves past — when, like many manufacturers in England, they built chassis only and deferred to the ubiquitous proprietary engine builder, Villiers, for their animation. The Ranger engine is a successful combination of the proven 37A Villiers lower half, complete with wide ratio transmission, and a Greeves square barrel and head. The finning on the upper end is most generous, well suited to chugging along at low speed for long periods without the benefit of high-volume air flow to carry away combustiongenerated heat.

An extra measure of confidence and performance is added in the person of a sturdy competition-type piston with a Dykes top ring and a fat steel cylinder liner which will readily accept a couple of rebores. The inlet and exhaust tracts of the engine are tailored to the intended duty with a Villiers S25/6 carburetor mounted on a longish manifold pipe — both items enhancing low-speed power by providing relatively high intake velocities at low revs — and a quiet expansion chamber/muffler.

One of the Ranger's strong points is, most certainly, its overall comfort. The bike-to-rider relationship is excellent when the firm but comfortable twinseat is employed, and the standing position is really superb, but not at all remarkable when the Ranger's heritage is taken into account. While regard for stand-up comfort might be considered a point concerning only scrambles or trials machinery, it must be remembered that the standing position offers the greatest degree of control on uneven terrain, regardless of speed or intent. And with particular regard to the Ranger's intent we feel that the out-of-theseat attitude is truly significant, because over unbelievably cobby ground the Ranger handles as well as the finest trials iron available.

Not only does the Ranger climb easily over logs and rocks, forge willingly through deep sand and muck, but it also does a more than passable job of dealing with rugged high-speed surfaces. It can, in fact, be run very hard with a high level of confidence. Much of the credit for the Ranger's dual-role ability can be given to the springer front end. We have been pleased to note in the year or so that these forks have been offered on Greeves for the American market that they have an uncanny versatility for both high-and low-speed running and evidence none of the sometimes undesirable characteristics of the old rubber-doughnut Greeves forks.

With all of its street-legal appointments, twinseat, passenger pegs, luggage rack and relatively quiet exhaust system, the Ranger must surely be considered as an adequate short-trip roadster. The only point that would mar its road worthiness, in fact, is that it comes shod with Dunlop Sport tires that can become quite savage when pressed hard on paved roads. If, however, the limitations of these really excellent dirt tires are accepted — and respected — the Ranger will turn a lackluster trip to the store into a pleasant bit of sport. With an eye to what the Ranger is really designed for, we readily accept the choice of rubber.

Greeves' good habit of building totally functional machines that simply refuse to fall apart is manifest in this bike. Weld and casting quality is excellent. Self-locking aircraft nuts are used exclusively, and the only manner in which pieces will leave the bike is through the application of a wrench. Typically, Greeves' emphasis on function has cost them beauty-contest points in the past, but the Ranger, despite its cobbiness and family resemblance, is a very attractive piece of equipment with its handsome light-blue fiberglass fuel tank and contrasting dark-blue frame. While chrome and polished alloy do not abound, what there is is of high quality.

The changes incorporated on the Ranger, from the Trail which it replaces, are the products of the thinking of distributor Nicholson, who has done a fine job of assessing his market. And with the ever-growing emphasis on good handling and performance, off the road, for multi-purpose bikes, the Ranger is going to find itself with more friends than it knows what to do with. ■

GREEVES

RANGER 250cc

$850