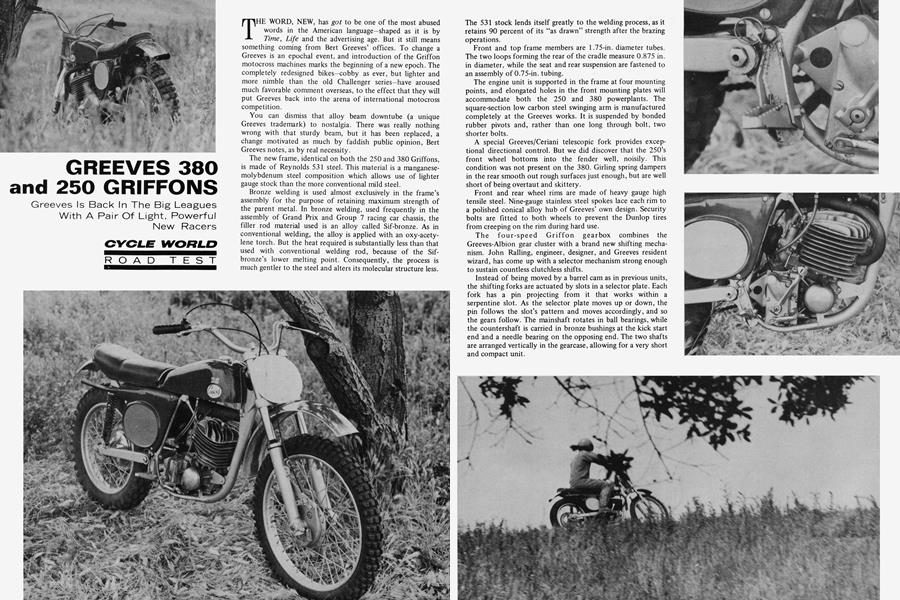

GREEVES 380 and 250 GRIFFONS

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

Greeves Is Back In The Big Leagues With A Pair Of Light, Powerful New Racers

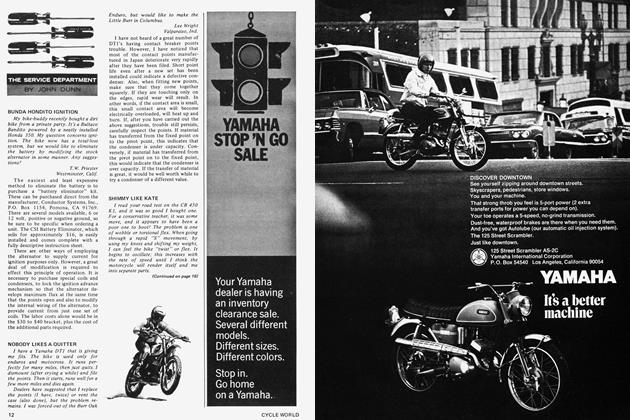

THE WORD, NEW, has got to be one of the most abused words in the American language-shaped as it is by Time, Life and the advertising age. But it still means something coming from Bert Greeves’ offices. To change a Greeves is an epochal event, and introduction of the Griffon motocross machines marks the beginning of a new epoch. The completely redesigned bikes-cobby as ever, but lighter and more nimble than the old Challenger series—have aroused much favorable comment overseas, to the effect that they will put Greeves back into the arena of international motocross competition.

You can dismiss that alloy beam downtube (a unique Greeves trademark) to nostalgia. There was really nothing wrong with that sturdy beam, but it has been replaced, a change motivated as much by faddish public opinion, Bert Greeves notes, as by real necessity.

The new frame, identical on both the 250 and 380 Griffons, is made of Reynolds 531 steel. This material is a manganesemolybdenum steel composition which allows use of lighter gauge stock than the more conventional mild steel.

Bronze welding is used almost exclusively in the frame’s assembly for the purpose of retaining maximum strength of the parent metal. In bronze welding, used frequently in the assembly of Grand Prix and Group 7 racing car chassis, the filler rod material used is an alloy called Sif-bronze. As in conventional welding, the alloy is applied with an oxy-acetylene torch. But the heat required is substantially less than that used with conventional welding rod, because of the Sifbronze’s lower melting point. Consequently, the process is much gentler to the steel and alters its molecular structure less.

The 531 stock lends itself greatly to the welding process, as it retains 90 percent of its “as drawn” strength after the brazing operations.

Front and top frame members are 1.75-in. diameter tubes. The two loops forming the rear of the cradle measure 0.875 in. in diameter, while the seat and rear suspension are fastened to an assembly of 0.75-in. tubing.

The engine unit is supported in the frame at four mounting points, and elongated holes in the front mounting plates will accommodate both the 250 and 380 powerplants. The square-section low carbon steel swinging arm is manufactured completely at the Greeves works. It is suspended by bonded rubber pivots and, rather than one long through bolt, two shorter bolts.

A special Greeves/Ceriani telescopic fork provides exceptional directional control. But we did discover that the 250’s front wheel bottoms into the fender well, noisily. This condition was not present on the 380. Girling spring dampers in the rear smooth out rough surfaces just enough, but are well short of being overtaut and skittery.

Front and rear wheel rims are made of heavy gauge high tensile steel. Nine-gauge stainless steel spokes lace each rim to a polished conical alloy hub of Greeves’ own design. Security bolts are Fitted to both wheels to prevent the Dunlop tires from creeping on the rim during hard use.

The four-speed Griffon gearbox combines the Greeves-Albion gear cluster with a brand new shifting mechanism. John Railing, engineer, designer, and Greeves resident wizard, has come up with a selector mechanism strong enough to sustain countless clutchless shifts.

Instead of being moved by a barrel cam as in previous units, the shifting forks are actuated by slots in a selector plate. Each fork has a pin projecting from it that works within a serpentine slot. As the selector plate moves up or down, the pin follows the slot’s pattern and moves accordingly, and so the gears follow. The mainshaft rotates in ball bearings, while the countershaft is carried in bronze bushings at the kick start end and a needle bearing on the opposing end. The two shafts are arranged vertically in the gearcase, allowing for a very short and compact unit.

The clutch is also new. It is all metal with seven steel and seven brass plates. The aluminum clutch drum is riveted to the double-row primary chain sprocket and spins on a ball bearing. Typical of the unit’s quality is the sculpturing given the clutch plates. Each of the steel driven plates is scalloped along the outer perimeter to engage with the 16 semicircular pegs integral with the clutch drum. The brass driving plates have been accorded the same treatment with semicircular cutouts which coincide with the steel pegs riveted to the inner pressure plate. The purpose of all this psychedelic shaping is to eliminate burring of the plates, an occurrence not uncommon in bike competition. An added plus is that the clutch can be removed as an assembly, complete with its seven springs. This extensive redesign has resulted in a clutch/transmission unit substantially narrower and 9 lb. lighter than its predecessor. It is also important to note that this dieting was achieved with no reduction of shaft or gear sizes, so reliability remains uncompromised. Transmissions of both machines are identical, but the 250 uses a 21-tooth engine sprocket while the 380 has a 25-tooth unit.

With dimensions of 80 by 72 mm, the 380 Griffon is definitely a big-bore powerplant. A large bore configuration will generate more heat than a narrow-bore long-stroke engine of equal size. In fact, heat dissipation was one of the bugs limiting two-stroke cylinder size until recent years. But the Greeves cylinders, particularly the 380, are graced with huge cooling fins which appear capable of dissipating heat from an engine of half again as much displacement. Both test bikes were thoroughly thrashed with no hint of excess heating.

Greeves has eliminated through-bolts to fasten the cylinder and head to the crankcase, and by doing so averted the problem of cylinder growth and end-loading. As a cylinder heats up, it grows, and the larger the cylinder, the greater its total growth. For this reason, the problem is rare in smaller displacement machines. Through-bolts restrict heat growth, consequently distorting the bore, mostly around the ports. This method of separately fastening the parts together is more expensive from a manufacturing standpoint, but is certainly justified for reliability’s sake. As an added benefit, the cylinders are stress relieved before machining, further minimizing irregular material behavior.

Starting either bike is easy with very little kickback or fuss, although the 380 has a 10.7:1 compression ratio and the 250, 11:1. The energy transfer ignition fitted to the machines deserves some credit for this, as it is a time-proven design and hardly a stranger to motorcycle competition.

Carburetion for the Griffons is administered by type 900 Amal concentrics, a 32-mm unit on the 380 and a 30-mm mixer for the 250. A 0.75-in. thick fiber spacer between the carburetor and manifold insulates the former from engine heat. Within those fiberglass side covers, each bike has two Fram air filters that open into a spacious plenum chamber. Air filtration is highly critical, above all for two-strokes, and it seems that Greeves has produced an excellent system.

Ground clearance for both machines is an airy 9.8 in., thanks mostly to the upswept exhaust pipes. While the 250 exhaust is of conventional single-pipe configuration, the twin exhaust port 380 has the two pipes that sweep over the cylinder head and merge into a single expansion chamber under the seat. With this arrangement, you’d think the heat of competition would be soon transferred to the rider’s posterior. Not so. CW testers, noted for journalistic sensitivity in that area, reported no such effects.

The full-length seat is very comfortable while allowing the rider to slide back all the way for maximum traction, a good feature for desert riding as well as motocrossing.

Immediate appearance of both machines is that they are very small. But they are ample to sit on, even for a very tall person, and feel quite tall. Because of the upright posture, neither bike lends itself to being leaned over and spun around turns on a fast, smooth track. The appropriate riding style is a straight-up one, with a lot of squaring off on turns. When trying to slide a turn by dropping your foot and “shoeing,” it seems to take forever for the bike to lean over and your foot to reach the ground.

While both machines have particularly wide power bands, in keeping with the motocross norm, the 250 genuinely surprised us with its tractability. One can expect rather brutish power from the 380 and not at all be disappointed, but such response from the 250 reveals a very competitive edge.

As the American motocross scene burgeons, and as larger numbers compete, often for money, many are discovering that the “scramblers” and converted desert sleds that used to win these events are no longer adequate. A specialized machine is needed and the Griffons reflect this. Where the Challenger was somewhat of a compromise bike, capable of several limited functions, a Greeves Griffon is definitely a motocross tool.

In evolutionary terms, the Griffon has gone far beyond the Challenger. Lighter, trimmer and more powerful, it reflects the changing complexion of both American and international competition. [Ö]

GREEVES 380 250 GRIFFONS