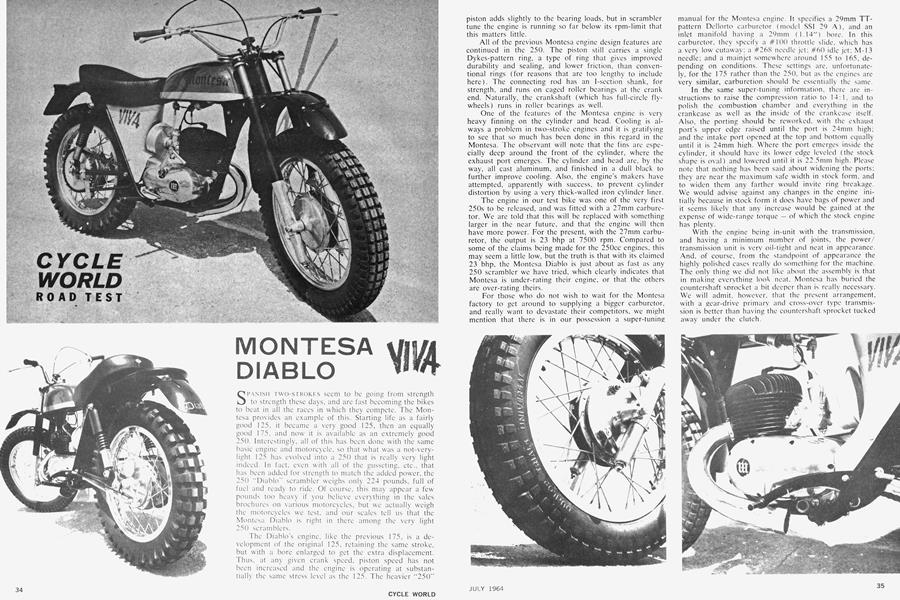

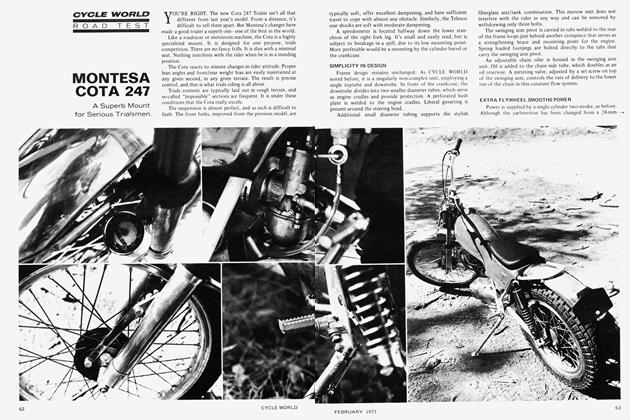

MONTESA DIABLO

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

VIVA

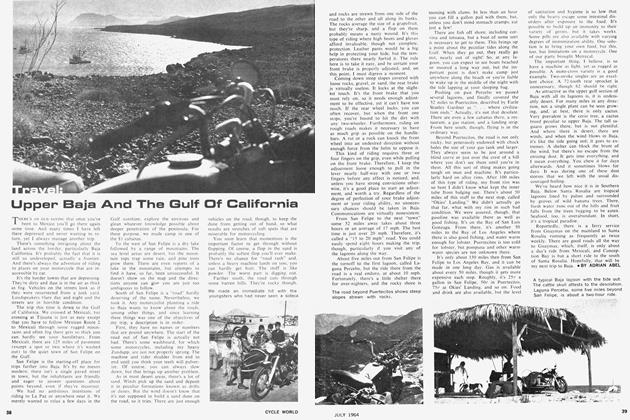

SPANISH TWO-STROKES seem to be going from strength to strength these days, and are fast becoming the bikes to beat in all the races in which they compete. The Montesa provides an example of this. Starting life as a fairly good 125, it became a very good 125, then an equally good 175, and now it is available as an extremely good 250. Interestingly, all of this has been done with the same basic engine and motorcycle, so that what was a not-verylight 125 has evolved into a 250 that is really very light indeed. In fact, even with all of the gusseting, etc., that has been added for strength to match the added power, the 250 "Diablo" scrambler weighs only 224 pounds, full of fuel and ready to ride. Of course, this may appear a few pounds too heavy if you believe everything in the sales brochures on various motorcycles, but we actually weigh the motorcycles we test, and our scales tell us that the Montesa Diablo is right in there among the very light 250 scramblers.

The Diablo's engine, like the previous 175. is a development of the original 125, retaining the same stroke, but with a bore enlarged to get the extra displacement. Thus, at any given crank speed, piston speed has not been increased and the engine is operating at substantially the same stress level as the 125. The heavier "250" piston adds slightly to the bearing loads, but in scrambler tune the engine is running so far below its rpm-limit that this matters little.

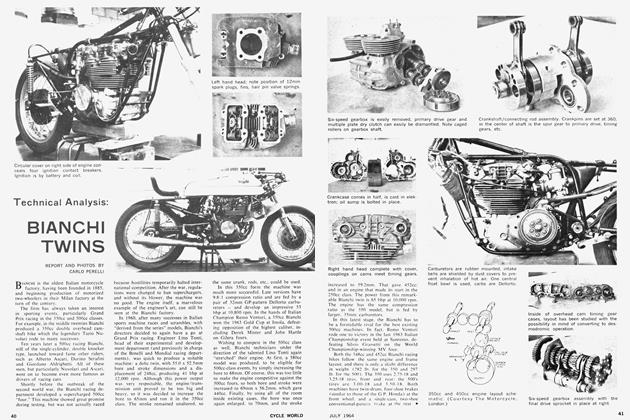

All of the previous Montesa engine design features arc continued in the 250. The piston still carries a single Dykes-pattern ring, a type of ring that gives improved durability and sealing, and lower friction, than conventional rings (for reasons that arc too lengthy to include here). The connecting rod has an 1-section shank, for strength, and runs on caged roller bearings at the crank end. Naturally, the crankshaft (which has full-circle flywheels) runs in roller bearings as well.

One of the features of the Montesa engine is very heavy finning on the cylinder and head. Cooling is always a problem in two-stroke engines and it is gratifying to see that so much has been done in this regard in the Montesa. The observant will note that the fins are especially deep around the front of the cylinder, where the exhaust port emerges. The cylinder and head are, by the way, all cast aluminum, and finished in a dull black to further improve cooling. Also, the engine’s makers have attempted, apparently with success, to prevent cylinder distortion by using a very thick-walled iron cylinder liner.

The engine in our test bike was one of the very first 250s to be released, and was fitted with a 27mm carburetor. We are told that this will be replaced with something larger in the near future, and that the engine will then have more power. For the present, with the 27mm carburetor, the output is 23 bhp at 7500 rpm. Compared to some of the claims being made for the 250cc engines, this may seem a little low, but the truth is that with its claimed 23 bhp, the Montesa Diablo is just about as fast as any 250 scrambler we have tried, which clearly indicates that Montesa is under-rating their engine, or that the others are over-rating theirs.

For those who do not wish to wait for the Montesa factory to get around to supplying a bigger carburetor, and really want to devastate their competitors, we might mention that there is in our possession a super-tuning manual for the Montesa engine. It specifies a 29mm TTpattern Dellorto carburetor (model SSI 29 A), and an inlet manifold having a 29mm (1.14") bore. In this carburetor, they specify a #100 throttle slide, which has a very low cutaway; a #268 needle jet; #60 idle jet; M-13 needle; and a mainjet somewhere around 155 to 165, depending on conditions. These settings arc, unfortunately, for the 175 rather than the 250, but as the engines arc very similar, carburction should be essentially the same.

In the same super-tuning information, there are instructions to raise the compression ratio to 14:1, and to polish the combustion chamber and everything in the crankcase as well as the inside of the crankcase itself. Also, the porting should be reworked, with the exhaust port's upper edge raised until the port is 24mm high; and the intake port opened at the top and bottom equally until it is 24mm high. Where the port emerges inside the cylinder, it should have its lower edge leveled (the stock shape is oval) and lowered until it is 22.5mm high. Please note that nothing has been said about widening the ports; they are near the maximum safe width in stock form, and to widen them any farther would invite ring breakage. We would advise against any changes in the engine initially because in stock form it does have bags of power and it seems likely that any increase would be gained at the expense of wide-range torque — of which the stock engine has plenty.

With the engine being in-unit with the transmission, and having a minimum number of joints, the power/ transmission unit is very oil-tight and neat in appearance. And. of course, from the standpoint of appearance the highly polished cases really do something for the machine. The only thing we did not like about the assembly is that in making everything look neat, Montesa has buried the countershaft sprocket a bit deeper than is really necessary. We will admit, however, that the present arrangement, with a gear-drive primary and cross-over type transmission is better than having the countershaft sprocket tucked away under the clutch.

The Montesa's frame is the same as before: a structure of steel tubing and a lot of gusseting plates, all welded together. It is not a thing of beauty, or a joy to the engineer s eye, but it is reasonably light and we have not heard of anyone breaking a Montesa frame. We would suggest that for anyone riding in rocky country, a big bashplate wrapped around and under the crankcase might be in order.

Also much the same as before is the bike’s suspension. Generally, this follows the now almost universal pattern of telescopic forks and swing arms, but the Montesa does seem to telescope and swing somewhat better than most. The suspension of the Diablo is, if memory serves us correctly, a bit stiffer than before, which means it is a little jouncy for cross-country riding but just right for today’s smooth, high-speed scrambles courses.

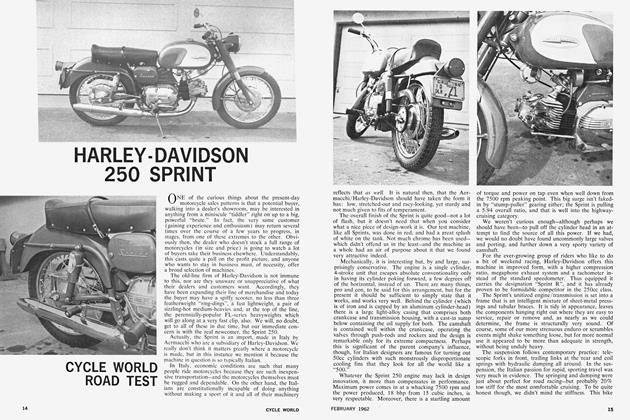

Wheels, tires and brakes rate a special mention. The first are beautiful light-alloy things, all polished and looking as though they have been borrowed from some Grand Prix road racing machine; they must weigh little more than a feather. The tires on our test bike were Dunlop, with a Trials Universal at the front, a Sport at the rear. However, the bikes will be delivered to dealers without tires and the customer will be able to specify the rubber he wants mounted at no extra cost. The Montesa distributors, knowing that conditions, and therefore tire requirements, vary around the country and between customers, have very wisely decided to make the choice of tires entirely optional. And finally, there are the brakes: these are the

same umts as are used on all other Montesas, but the Diablo scrambler has closed backing plates, to keep sand out of the brake’s internals. It goes without saying that the brakes are far more than adequate in a scrambler.

This latest Montesa has a better air-cleaner than the first example we tested, but it is still not all that it should be for conditions one finds in the western United States. The stock Montesa air cleaner will filter out sand, rocks, twigs and low-flying birds, but the terribly abrasive dust that is a standard feature of southwestern scrambles events will go right through. There is, fortunately, room for a good, effective fiber-element cleaner and we expect that most western riders (the smart ones) will want to add such a devise.

While in the area of the carburetor, we should mention that the Spanish Amal fitted to the Montesa has a mainjet accessible from the side, which has enabled Montesa to mount the carburetor almost level. On altogether too many two-strokes, the fact that the jet is located in the bottom of the carburetor has forced a steep down-draft mounting (to give clearance between the bottom of the carburetor and the top of the transmission) and this means that there is likely to be a steady dribble of fuel from the idle passages if the fuel tap is left “on” when the engine is not running. The layout on the Montesa eliminates that problem.

We had some difficulty in trying to start the Montesa. Sometimes it would fire rather quickly; and at other times it proved to be very balky indeed. This was, it seems, mostly due to our lack of familiarity with the machine, as Kim Kimball, who is the distributor for the things, could get it to start with a minimum of prodding any time he pleased. This is mentioned simply to advise the new Montesa owner that there is a correct combination, even though we are still not certain what it might be. Perhaps you have to “live” with the machine long enough to become soul-mates.

One thing that no one had to tell us was that the Diablo handles very well. The fact that it is light is a great help, but it has a natural balance that does a lot for the handling, too. On a slippery surface, the bike feels a trifle slithery at the rear wheel, but that is only because it has bags of torque, and not much throttle is required to start the rear tire spinning loose.

In all, the Montesa Diablo 250 scrambler was the sort of bike that makes us expect great things of it. It is very well finished, and feels nearly unbreakable. The performance, both speed and handling, are exceptional, and if the bike matches our expectations, it will become the terror of the 250 class before the summer is over. Of course, others in the class are not exactly asleep, so the Montesa will have competition, and if the competition is as good as the Montesa itself, the 250 class, which is ferociously fast now, will be enough to make strong men weep, and the faint of heart switch to something less fierce — like a good 500. •

MONTESA

DIABLO SCRAMBLER

SPECIFICATIONS

$785

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue