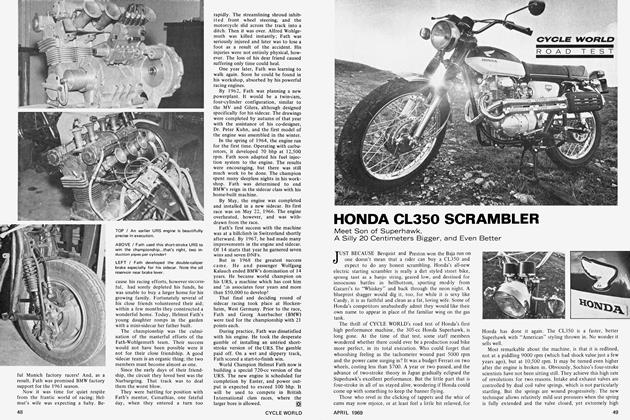

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

"I know, indeed, the evil of that I purpose; but my inclination gets the better of my judgment — EURIPIDES

TELL US, if you can, who built the world's most powerful road racing motorcycle? Should the names of famous Italian multis come to mind, then try again; you aren't even warm. As a matter of fact (and this will make Count Agusta's jaw muscles tighten) the bike in question is a Harley-Davidson, with elaborations by the Milwaukee firm's racing department and that little old California Speed-Tuner, Jerry Branch. We have called this creation "Super Sportster," because that is the most accurate capsule description that comes to mind. It is a Sportster (at least the engine is) and it is most definitely Super. More powerful than a locomotive and faster than a speeding bullet. For sheer muscle, skinny little bikes like the MV or Gilera "fours" aren't in the same class. Thus far, there is only one Super Sportster in existence and that may be a good thing. In any case, one does exist, and all because our Madcap Technical Editor has more imagination than prudence.

The Super Sportster was born when Madcap suggested that an 82 bhp XLR-series engine Branch had (on loan, from H-D's racing department) might give one of Harley-Davidson's KR road racing bikes an interesting boost in performance. No sooner said than done. Jerry Seguin's KR was borrowed for the experiment, its flathead "45" engine removed and the XLR dropped in. Due to the added height of the XLR engine (overhead valves), the original KR fuel tank had to be abandoned, but the actual conversion presented no other problems.

Because the engine originated from Harley-Davidson's racing department, one might assume that it incorporates a lot of mysterious and wonderful speed secrets. In point of fact, with the exception of the cylinder heads anyone could duplicate the entire setup by following the procedures set forth in our June, 1965 issue article about the KR engine.

Starting with a set of standard cylinder heads, and using flow-test equipment and dynamometer, Harley-Davidson technicians developed optimum porting. This entailed a lot of fill-welding and reshaping with a grinder, but the results would seem to justify the effort (which amounts to about $3000 in labor). In fully-developed form, the ports are not particularly smooth and the shape does not look "right," which was all rather surprising. Because of this, we made a tongue-in-cheek offer to "take a grinder and clean them up." That brought a warning of dire consequences if we so much as rubbed a finger too hard inside the ports. Mr. O'Brien, who heads Harley-Davidson's racing department, has a lot of blood, sweat and tears invested in those heads and doesn't want them touched until they have been carefully measured and can be duplicated. Incidentally, we should mention that our fun-andgames session with the Super Sportster has been interrupted while the cylinder heads are in use at Bonneville in Harley-Davidson's record-attempt engine.

Standard XLR valves are used in these heads, in conjunction with Sifton aluminum-alloy spring collars and pushrods. The rocker-arms have been polished to eliminate stress-raisers and reduce the possibility of breakage. Branch cautions against lightening the rockers; if much material is removed the rockers will flex, which upsets the valve timing enough at high revs to cause a drop in power.

In the matter of cams, we have one of those peculiar situations where a racing, engine is given less radical valve timing than the equivalent street engine. At present, stock Sportsters are fitted with "P" cams, which give 8282, 85-80 valve timing. The Super Sportster uses the new "PB" cams, which open the intake valves 77-degrees before top center and close them 87-degrees after. Exhausts open 92-degrees before bottom center and close 75-degrees after top center. That provides a total intake duration of 344-degrees with an overlap (while both intake and exhaust valves are open) of 152-degrees. Lift is .415-inch. Sportster owners might be interested to know that these PB cams will soon be available at their local, friendly Harley-Davidson dealer.

Feeding mixture to Dick O'Brien's priceless ports is the new diaphragm-type Tillotson carburetor that is a standard item on all new Sportsters. It is an impressive instrument. The conventional float chamber has been eliminated, and a fabric-reinforced neoprene diaphragm, responding to the pressure-drop in the venturi, controls (via a needle-valve) the flow of fuel. Other manuallyadjusted needle-valves are used to set the mixture for idle, middle-range and full throttle conditions and there is even an accelerator pump.

The new Tillotson is not affected by vibration or position (it would function equally well upside-down, or down-draft, or even up-draft) and will give the rider remarkably-smooth throttle response. Its only failing is that the range of adjustment makes it possible to get it hideously out of tune. A considerable amount of fiddling was required before our fire-breather Super Sportster would run cleanly from 4000 rpm, where it climbs up "on the cam" to 7000 rpm where it is red-lined. In the testing that accompanied this fiddling, we also discovered that when it does not run cleanly, it is impossible to ride. Those little burbles and stutters that are so annoying with lesser motorcycles are magnified to the point of being lethal by the Super Sportster's 82 horsepower engine. It jerks and lurches so badly as to be quite unmanageable. But, once correctly adjusted, the Tillotson carburetor gives the best, smoothest response of anything we have tried — even though it has a mighty, 1 5/8-inch throttle bore (with a 1 5/16-inch venturi).

HARLEY-DAVIDSON SUPER SPORTS

One of the nice things about the Harley-Davidson is the wide range of ratios available for the transmission. There are at least 16 combinations, and these can be changed quickly enough to make tailoring the box at the the track a practical proposition. A complete change of ratios can be made in an hour. For our tests (which, in this case, includes some racing.) Branch fitted the closeratio "J" gearset, with ratios of 1:1, 1.14:1, 1.51:1 and 2.09:1 for 4th through 1st, respectively.

After an initial shake-down outing, we went to Riverside Raceway with the Super Sportster to get in some practice time and to gather some information on performance. In deference to the heavily-stressed drive-train components, we did not try any drag-strip runs, which would not have given a true indication of what the bike will do. The Super Sportster is a road racing machine, and not geared to show its stuff at under 40 mph — where it comes on the cams in low gear. We do know that with its road race gearing, it will smoke right past hot street Sportsters that consistently run 115-120 mph in the quarter. This was, of course, from 40 mph and up.

It was our intention to try for top speed, and it was thought that the 3.69:1 overall ratio would be about right for Riverside Raceway's one-mile "long-course" straightaway. However, before the test progressed that far, we found to our amazement that the approximately half-mile short-course straight was plenty. The Super Sportster would pull the full 7000 rpm there, which was a staggering 149 mph. There is every indication that the bike would pull a 3.08:1 ratio at, say, Daytona, and reach 180 mph in road racing trim. As we have said before, a similar machine, but with a less-fierce engine (70 bhp), has been timed at slightly over 170 mph along Daytona's back straightaway.

Another big surprise was the Super Sportster's handling. By normal road racing standards, the KR chassis is not a very impressive item. Too narrow, light in the wrong places, and with peculiar-looking springs and dampers at the rear. Despite all this, the Super Sportster did handle quite well; perhaps not on par with a Manx Norton, but near enough the equal of a Matchless G-50 once it was bent into a turn. The only real problem was that it has quite a high center of gravity, because of those all cast-iron cylinders and heads, and one must really work to pull the Super Sportster down into a turn. Also, on any tight, slow turn, the long wheelbase makes the bike cumbersome. And, when you combine long wheelbase and high center of gravity with 82 rather nervous horsepower, the slow stuff becomes difficult in the extreme.

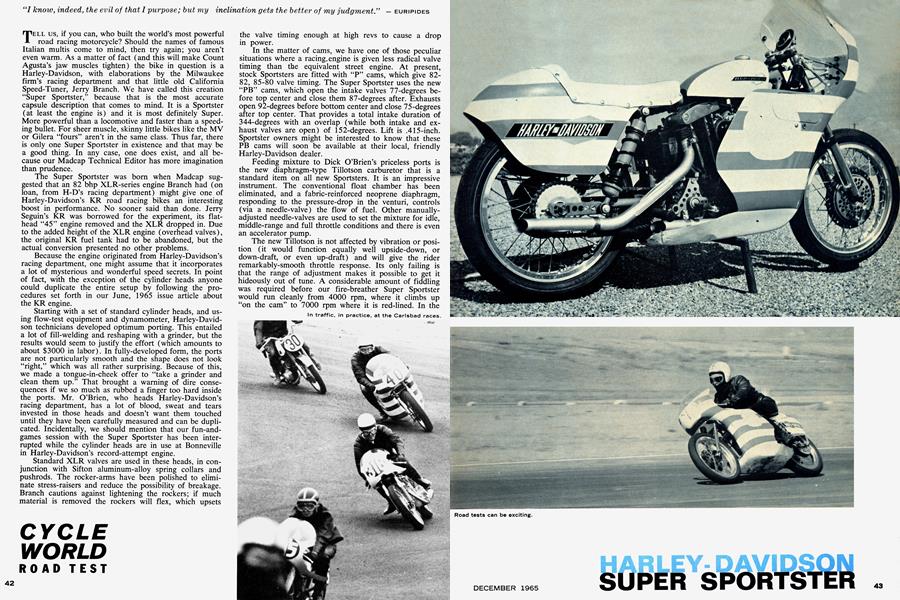

As an addendum to our regular testing, CYCLE WORLD'S terrified Technical Editor ran the brute in a road race, which gave us an opportunity to compare the Super Sportster with, other road racing equipment. In terms of pure speed, there isn't much comparison. Don Vesco, riding his very rapid Matchless G-50 (which did 129.9 mph to qualify 6th fastest for the Daytona 200) said that in practice, the Super Sportster thundered past him like a Chrysler-powered dragster making the same sort of noise.

During practice, much was learned. It was, as has already been stated, not the handiest thing in the world around tight turns, and that is what Carlsbad Raceway (where the competition was held) has in abundance. Especially at "Crasher's Hairpin" it was losing distance to less lengthy, more nimble motorcycles. Another problem, of sorts, was the huge surplus of horsepower. At almost any point around this twisting, 1.3-mile course, full throttle would provoke a great blast of wheelspin. The Super Sportster would snake slightly under acceleration away from all the slow turns, and there was more of the same going uphill along the back "straightaway." Someone remarked at the time that it looked a bit like a rail-job dragster trying to cut a fast lap around a go-kart course. Still, Our Hero appeared to enjoy himself, with appropriate reservations about how quickly one can get into terrible difficulties with 82 bhp on tap. The brakes showed some deficiencies, too, but would stabilize at about 70-percent effectiveness after a few laps. To their credit, it should be pointed out that nothing else in this world works its brakes like the Super Sportster.

One thing that would have really put a fine frosting on this test cake, a big victory, was not to be. The bike certainly had the potential, and for a time, in practice, it even appeared that its pilot might be up to the task. A mysterious carburetion malady prevented the Super Sportster from doing anything in the race. It failed to fire on the start, ran very badly for a few laps (before its rider decided that the next fit of misfiring might unseat him) and then retired. Investigation later proved the problem to be simply a too-full fuel tank. Because fuel consumption is quite high, and the race long, the tank was filled to brimming. Heat, from the engine, caused the fuel to expand and the resulting pressure, not being able to force out the tank-vent quickly enough, was flooding past the metering needle in the carburetor.

This will be corrected for the next race and there will be a next race for the Super Sportster. The OI' Tech. Ed. has gone mad as a hatter for the brute, and is even now drawing up a short-chassis frame. Will it get that new frame? Will its rider survive the race? Will the Editor/ Publisher get an ulcer? Stay tuned for the further adventures of Super Sportster, the All American fire-breather.

HARLEYDAVIDSON SUPER SPORTSTER

View Full Issue

View Full Issue