A DUCATI 250 FOR RACING

... high, apple pie, in the sky, hopes.

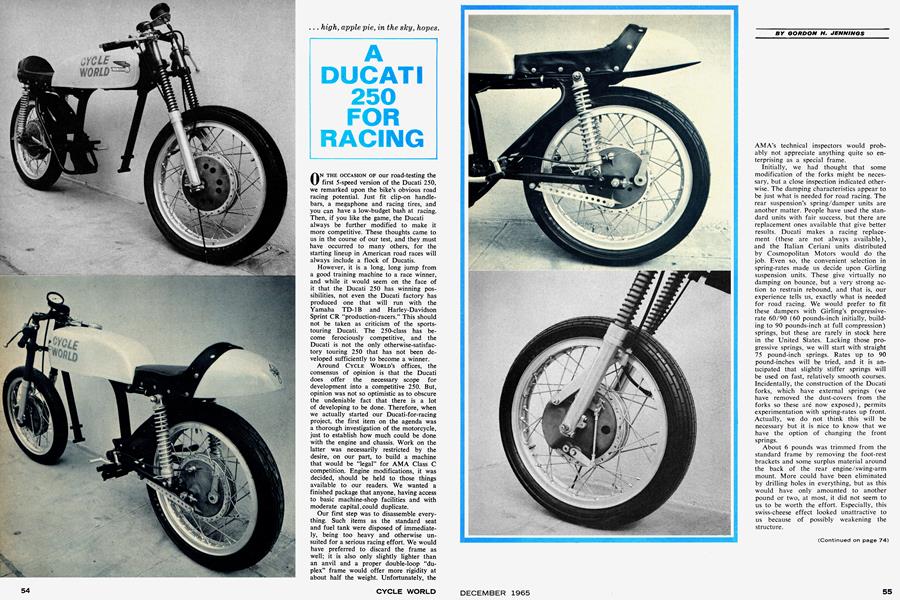

ON THE OCCASION OF our road-testing the first 5-speed version of the Ducati 250, we remarked upon the bike's obvious road racing potential. Just fit clip-on handlebars, a megaphone and racing tires, and you can have a low-budget bash at racing. Then, if you like the game, the Ducati always be further modified to make it more competitive. These thoughts came to us in the course of our test, and they must have occurred to many others, for the starting lineup in American road races will always include a flock of Ducatis.

However, it is a long, long jump from a good training machine to a race winner, and while it would seem on the face of it that the Ducati 250 has winning possibilities, not even the Ducati factory has produced one that will run with the Yamaha TD-IB and Harley-Davidson Sprint CR "production-racers." This should not be taken as criticism of the sportstouring Ducati. The 250-class has become ferociously competitive, and the Ducati is not the only otherwise-satisfactory touring 250 that has not been developed sufficiently to become a winner.

Around CYCLE WORLD'S offices, the consensus of opinion is that the Ducati does offer the necessary scope for development into a competitive 250. But, opinion was not so optimistic as to obscure the undeniable fact that there is a lot of developing to be done. Therefore, when we actually started our Ducati-for-racing project, the first item on the agenda was a thorough investigation of the motorcycle, just to establish how much could be done with the engine and chassis. Work on the latter was necessarily restricted by the desire, on our part, to build a machine that would be "legal" for AMA Class C competition. Engine modifications, it was decided, should be held to those things available to our readers. We wanted a finished package that anyone, having access to basic machine-shop facilities and with moderate capital,could duplicate.

Our first step was to disassemble everything. Such items as the standard seat and fuel tank were disposed of immediately, being too heavy and otherwise unsuited for a serious racing effort. We would have preferred to discard the frame as well; it is also only slightly lighter than an anvil and a proper double-loop "duplex" frame would offer more rigidity at about half the weight. Unfortunately, the AMA's technical inspectors would probably not appreciate anything quite so enterprising as a special frame.

GORDON H. JENNINGS

Initially, we had thought that some modification of the forks might be necessary, but a close inspection indicated otherwise. The damping characteristics appear to be just what is needed for road racing. The rear suspension's spring/damper units are another matter. People have used the standard units with fair success, but there are replacement ones available that give better results. Ducati makes a racing replacement (these are not always available), and the Italian Ceriani units distributed by Cosmopolitan Motors would do the job. Even so, the convenient selection in spring-rates made us decide upon Girling suspension units. These give virtually no damping on bounce, but a very strong action to restrain rebound, and that is, our experience tells us, exactly what is needed for road racing. We would prefer to fit these dampers with Girling's progressiverate 60/90 (60 pounds-inch initially, building to 90 pounds-inch at full compression) springs, but these are rarely in stock here in the United States. Lacking those progressive springs, we will start with straight 75 pound-inch springs. Rates up to 90 pound-inches will be tried, and it is anticipated that slightly stiffer springs will be used on fast, relatively smooth courses. Incidentally, the construction of the Ducati forks, which have external springs (we have removed the dust-covers from the forks so these aré now exposed), permits experimentation with spring-rates up front. Actually, we do not think this will be necessary but it is nice to know that we have the option of changing the front springs.

About 6 pounds was trimmed from the standard frame by removing the foot-rest brackets and some surplus material around the back of the rear engine/swing-arm mount. More could have been eliminated by drilling holes in everything, but as this would have only amounted to another pound or two, at most, it did not seem to us to be worth the effort. Especially, this swiss-cheese effect looked unattractive to us because of possibly weakening the structure.

(Continued on page 74)

At present, the CYCLE WORLD Ducati still has its friction-type steering damper. In touring use, this is a good thing, lending stability over humps and bumps in the road surface. Racing is another matter. To get the desired delicacy of control, one must keep the friction damper quite slack; too slack, in fact, to be of much benefit. Where a damper is really needed is in recovering from a slide: the rear wheel steps-out, you correct, and when the bike straightens, its forks will flick right over on opposite lock. This results because "trail" yanks the forks back toward center, after which inertia carries them over near full opposite lock. Following this, they will again be swung back toward center and again inertia will over-do things for the rider. On a good handling bike, these oscillations lose amplitude with each successive cycle, and disappear without doing any damage (usually). Sometimes however, with even the best of motorcycles they will occur with such violence that the rider will be thrown off. The only damper capable of correcting this condition is the hydraulic type, which is velocitysensitive. Hydraulic dampers have no effect on small, low-speed steering oscillations, but they will prevent the forks from flapping. Before we try any serious racing, the friction damper will be removed, and a hydraulic damper substituted.

A lot of people have tried to make touring brakes do a racing job, and to the best of our knowledge, this has never been entirely successful. So, just to nip-off a budding problem, we ordered a set of Oldani brakes from Italy. These have 200millimeter (7.88-inch) drums, cast of magnesium alloy with riveted-in iron liners. The front brake has double-leading shoe actuation; the rear, single. A flange is provided for mounting the rear wheel sprocket but it is rigid, instead of the cushion-drive hub of the standard Ducati. To take shock out of the drive, a spring-hub Oldani sprocket is supposed to be used with the Oldani rear hub. We have another idea for the sprocket arrangement which will be explained next month. Cushion-hub Oldani sprockets are rare, and we are trying to use as many readily-available parts as possible.

Clip-on bars, complete with control levers, can be obtained from Berliner Corporation, the Ducati Distributors, and we elected to use these. They are made to fit the bike and you won't find anything better. Fuel tank and fairing both came from Custom Plastics. The use of Goodyear road racing tires should not need explanation. Proper racing tires are absolutely essential, and our experience with the Goodyears indicates that they are at least as good in terms of adhesion as anything available. They are also somewhat expensive, but the wear-rate is so low that when one considers frequency of replacement, the Goodyear tires are a racing bargain.

This brings us to the end of the chassis modifications; at least, until testing indicates what other small changes will be needed. Next month, we will delve into the matter of engine work, which is a great deal more involved.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Round Up

December 1965 By Joe Parkhurst -

[technicalities]

December 1965 By Gordon H. Jennings -

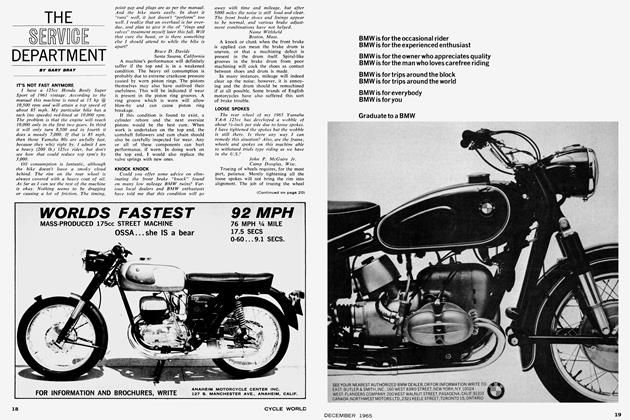

The Service Department

December 1965 By Gary Bray -

Letter

LetterLetter

December 1965 -

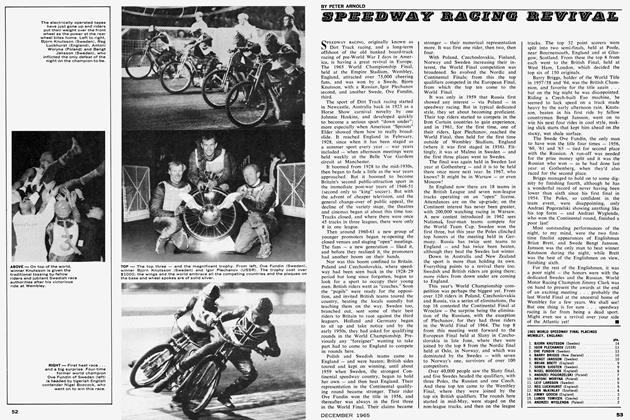

Speed Way Racing Reviyal

December 1965 By Peter Arnold -

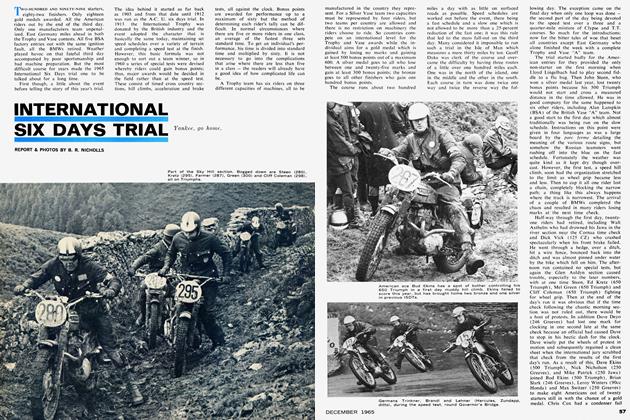

International Six Days Trial Yankee, Go Home.

December 1965 By B. R. Nicholls