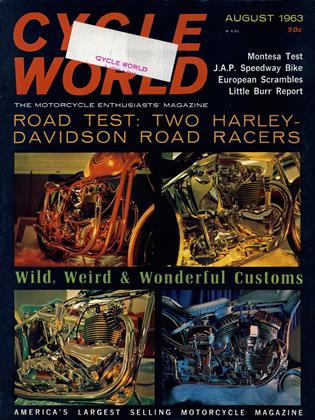

HARLEY-DAVIDSON KR-TT & SPRINT CR-TT

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

RACE FAVORITES come and go, except for HarleyDavidson, who were hard to beat 10 years ago (or 20, for that matter), are hard to beat right now, and it looks as though they might be hard to beat 10 years hence. The reason behind their success is not as straightforward as it might seem. Many people credit their performance to the fact that, in Class C competition, they have a 50-percent displacement advantage - that margin being allowed for flathead engines running against those with overhead valves. This is, in part, correct, but had Harley-Davidson not been willing to spend the time and money to develop their flathead to a level that would have seemed impossible a few years ago, they certainly would not be winning races today. Evidence of the amount of effort they put into racing is also present in the competition record of their Sprint, which has absolutely no design features that would give it an advantage over any other 15-incher, but wins races anyway. The key to the whole thing is in having machines that are strong enough to stay in one piece even when forced very hard, and in applying the developmental resources to make the engines deliver all of the power their innards will stand.

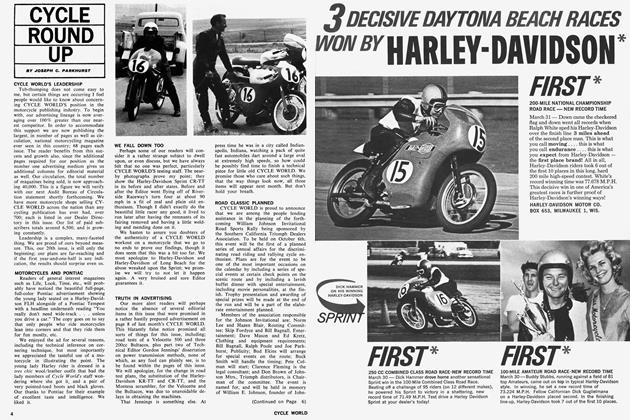

And just how fast, and strong, are the Harley-Davidson racing bikes? We are sure many people have wondered, and when the opportunity presented itself for our staff to look into the matter firsthand, no time was lost in bringing the machines to the test. The particular examples offered to us were Dick Hammer’s KRTT and Sprint 100 (or CRTT) road racers, with which he acquitted himself so admirably at the recent AMA Daytona meet, winning the 15-inch Open race and leading the National Championship event until engine problems took him out of the hunt. Both bikes were in excellent order for our test; the Sprint because it was still healthy after its win; the KRTT because Jerry Branch (the talented tuner who works such wonders with Hammer’s machines at Long Beach, Calif., Harley-Davidson) had completely rebuilt it after its return from Daytona.

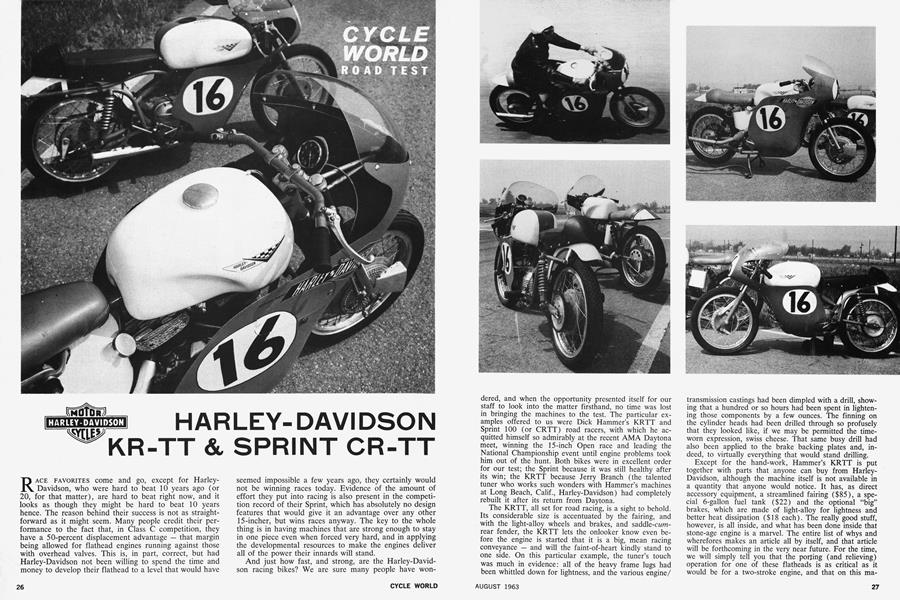

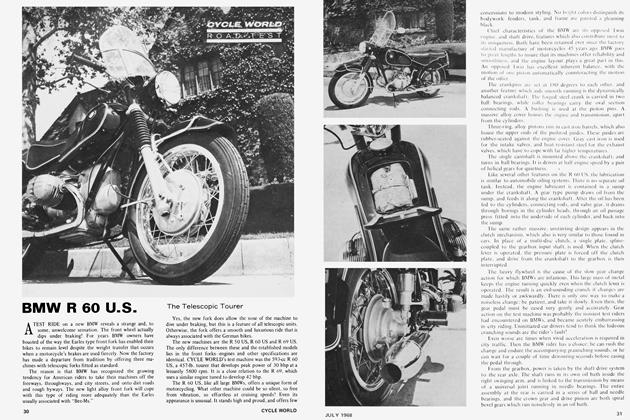

The KRTT, all set for road racing, is a sight to behold. Its considerable size is accentuated by the fairing, and with the light-alloy wheels and brakes, and saddle-cwmrear fender, the KRTT lets the onlooker know even before the engine is started that it is a big, mean racing conveyance — and will the faint-of-heart kindly stand to one side. On this particular example, the tuner’s touch was much in evidence: all of the heavy frame lugs had been whittled down for lightness, and the various engine/ transmission castings had been dimpled with a drill, showing that a hundred or so hours had been spent in lightening those components by a few ounces. The finning on the cylinder heads had been drilled through so profusely that they looked like, if we may be permitted the timeworn expression, swiss cheese. That same busy drill had also been applied to the brake backing plates and, indeed, to virtually everything that would stand drilling.

Except for the hand-work, Hammer’s KRTT is put together with parts that anyone can buy from HarleyDavidson, although the machine itself is not available in a quantity that anyone would notice. It has, as direct accessory equipment, a streamlined fairing ($85), a special 6-gallon fuel tank ($22) and the optional “big” brakes, which are made of light-alloy for lightness and better heat dissipation ($18 each). The really good stuff, however, is all inside, and what has been done inside that stone-age engine is a marvel. The entire list of whys and wherefores makes an article all by itself, and that article will be forthcoming in the very near future. For the time, we will simply tell you that the porting (and relieving) operation for one of these flatheads is as critical as it would be for a two-stroke engine, and that on this machine the combustion chamber has been opened (in the interest of high-speed breathing), to the extent that the compression ratio is only 6:13:1. The cams used open the intake valves 68-degrees before top dead center, and close them 66-degrees after bottom dead center, giving a total duration of no less than 314-degrees. The exhaust valves open 58-degrees before bdc, and close 42-degrees after tdc, for a duration of 280-degrees. If, from this, you get the impression that there is always a valve standing open, then you are very nearly right. One interesting aspect of this engine is that its low compression ratio enables it to run quite satisfactorily on Mobil regular-grade gasoline, and that is what is used in it for racing.

Power output from this engine is 48 bhp @ 6800 rpm, by the SAE rating method, measured at the rear wheel and adjusted for air density. Torque reaches its maximum of slightly over 50 lb-foot at 5000 rpm and, frankly, the engine gets down under its cams very badly at anything less than 4500 rpm and there is practically no torque at all if the rider allows the engine to drop below that speed. On the other hand, the transmission ratios are staged closely enough so that there is no excuse for getting “off the cam.” The engine pulls very strongly from 5000 rpm right up to 7000 rpm — after which it fades quite sharply — and that gives the rider a good, fat 2000-rpm spread to carry him along. A lot of clutch-slip is needed to make a fast start when pulling the tall roadracing gearing, and the first 20 feet or so are nothing to shout about, but after that — gangbusters.

Harley-Davidson’s road racing Sprint much more nearly resembles the standard touring-type product than the KRTT. It is, however, outfitted with a great many special engine, transmission and suspension parts, and therein lies quite a difference. Our test bike was prepared at the factory, and had special wheels and brakes, and all of the non-essentials removed. A big fuel tank, clip-on handlebars, racing fairing and stern-stop racing saddle made it look like a racing machine, and a considerably modified engine made it go like one.

There are no obvious engine alterations, unless you have a sharp eye and happen to notice that the cylinder barrel is of aluminum alloy, and not cast-iron. Inside, though, there have been some improvements. An RS-5 cam-shaft, high-compression piston, special valve gear' (stronger springs, lighter retainers, etc.) and meticulous assembly. Also, the cylinder head itself is a special part, having larger ports and valves. The carburetor on this racing Sprint is a TT-pattern Dellorto, and the engine exhausts into a short pipe fitted with a reverse-cone megaphone. Nothing radical in here — except the way it performs. The Sprint engine’s stroke is unfashionably greater than its bore, and one would assume that, as a result, it would be a low-speed torque-er. That notion is quite wrong. Somehow, by working real magic with the valvegear and depending on the engine’s inherent strength to hold all of the bits glued together, Harley-Davidson’s engineers have persuaded this long-stroke single to crankoff revolutions like few others of any specification will. Maximum power is developed at 9500 rpm (which is also supposed to be the rev’ limit) but under determined urging, it will slip up to around 10,000 rpm. A slight tailwind, which blew briefly down the Riverside Raceway straight, produced that 5-figure tachometer reading once in top gear, and Dick Hammer tells us that at one point in the Daytona race, he was pulling 10,500 in top gear. However, we used only 9500 as a shifting point, out of deference to an engine that had been giving its all for what were already too many racing miles for absolute reliability.

We spent about a day and one-half banging around Riverside Raceway (our favorite course) on the Sprint and KRTT and it was both a thrill and an education. The KRTT proved to be just as horrendously fast as we had anticipated and the Sprint was a complete revelation.

For sheer speed, we do not think that any of the other Class-C competition bikes can touch the KRTT. It comes out of corners like a rocket, and we were rather surprised to discover that it would peak at about 7000 rpm in fourth cog long before we ran out of room on the long Riverside Raceway straight. That is, if you care to glance at the data page, in excess of 140 mph. We did not time every run down the straight, but did record a best run of 142.3 mph with a tach reading of slightly over 7000 rpm. At other times, with the aid of a very slight wind (most of the time the air was virtually dead) we saw tach readings of about 7200 rpm, or 145 mph — and that was done with the engine running past the power peak. Pulling a bit more gear, the KRTT would very likely exceed 150 mph, which is buzzing along fairly briskly in anybody’s league.

At the termination of those 140-mph runs, you sit up straight and clamp on the brakes for the approaching turn, learning two very interesting things in the process. First, there is the force of the wind when one pops up from behind the fairing, which tries to pry the rider off and sets the skin on his cheeks fluttering (assuming that he has not nervously clenched his jaws). Second, you notice that even the special brakes do not really feel strong enough to slow the machine quickly. We encountered no fade, but the overall braking performance of the KRTT was so much inferior to that of the Sprint (whose brakes do not, admittedly, have quite so much to do) that it created in us a definite feeling of dissatisfaction. Whether we would be so critical of the KRTT’s brakes if the Sprint had not been there we do not know.

In the area of handling, the KRTT also suffers in comparison with the Sprint. Of course, its super-abundance of power does create special problems for the rider, and on Hammer’s big bike, the problem is further complicated by the fact that the lightening operation on the rear suspension’s swing arm was carried a trifle too far, and there is some flexing under power. Jerry Branch readily admits that he had overstepped the limit in lightening the swing arm, and it is to be strengthened, which will improve the bike’s behavior.

Apart from this tendency of the rear wheel to do a little steering on its own as the throttle was opened and closed, the KRTT was somewhat more manageable than we had been thinking. It is too big to be very agile running down through a series of right-and-left bends, but once you get it cranked over and on the line it is steady and quite fast. The KRTT is decidedly headstrong, and in the hands of an inept or inexperienced rider it could be a bit lethal, but a good rider, with experience, can get it around just about as fast as anything available.

In sharp contrast, the Sprint is smooth and agile, going precisely where it is pointed (within reasonable limits) and giving the rider, experienced or not, a maximum opportunity for going fast without getting into trouble. The engine hauls the Sprint along at a pace that has the rider thinking he is astride a 30-incher much of the time and the road-holding is so good that the power can be used very early when exiting from a turn. As a result, one’s progress around the twisty sections of a road circuit is apt to be just as fast, or faster, than would be possible on the average bike with twice the engine displacement. And, as we intimated before, the Sprint has tremendous brakes. Throughout the test, we constantly found that we had started braking too soon for corners, and could have gone in much deeper.

However difficult it might be to get into trouble with a motorcycle, it can be done if one presses the bike beyond the limit — and our esteemed editor did approximately that. While negotiating Riverside’s fast esses, he diverted his attention long enough to fiddle with the carburetor’s mixture-slide control and shot off of the road at about 90 mph, going down into a gulley and terminating what had been a very spirited ride in a cloud of dust and a hearty rending of leathers. Fortunately, he emerged from the incident with injuries principally to his pride, and with equally minor damage to the machine. We removed the fairing, which was rather badly battered, and continued without further drama. This was, incidentally, the first time we have dropped a test bike, but it will probably not be the last; test riding is useless unless done with enough vigor to determine how good, or badly, a bike handles and it doesn’t take much to place matters completely out of hand when treading very near the edge.

After doing our handling and high-speed testing, the KRTT and Sprint were hauled off to the drag strip. The Sprint, with road racing gearing, was a little sluggish away from the mark, and its elapsed time was nothing outstanding, but the terminal speed of very nearly 90 mph was exceptional for a 15-incher. The KRTT was tinkered with, changes of gearing and all that, and finally got down to a mighty 12.7 seconds, with a top speed of 103.4 mph. Once the gearing was changed, the KRTT would go away from the line with the rear tire smoking and leaving a long, black squiggle behind. Standing-start runs are not this machine’s strong suit, of course, but it was agreeable to that sort of work with the right combination of sprockets.

In all, this was a bit of testing that we will not soon forget. It left us with a lot of respect for the racing Harley-Davidsons and the men who tune and ride them, and it will probably be some time before we have an opportunity to go so fast (the KRTT) or corner with such verve (the Sprint) again. •

HARLEY-DAVIDSON

ROAD RACERS

H-D SPRINT 100

$900

H-D KRTT

$1295