NORTON 750 ATLAS

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

Norton

ONE YEAR AGO, give or take a few days, we were given a Norton Manxman to road test, and while there were a few things about the machine that we thought could be improved (we think every motorcycle can be improved), it still left us very impressed indeed. Now, after the passage of twelve months, and after the testing of a great many more motorcycles, we have been given another Norton, the Atlas, and we are pleased to report that it is even better than the Manxman.

The major (and virtually the only) difference between the Manxman and the Atlas is the engine. The Manxman’s engine is a stroked version of the original 500 Dominator, and with a “sport” camshaft and dual carburetors it produced a claimed 52 bhp at 6500 rpm. The Atlas is much the same engine, but with a bore enlarged from 2.68 to 2.98 inches, boosting its displacement to 745cc; up from the Manxman’s 646cc. We have no specific engine data beyond a vague statement that the Atlas has “in excess of 60 bhp at 65 rpm,” but we believe that little has been done but the increasing of the displacement. If that is true, it has been enough. The Atlas is, if memory serves us correctly, a less fussy machine than was the Manxman: more willing to run very slowly and more agreeable about starting when cold. It seems to be utterly without temperament, and is equally willing to slog along at less than 1000 rpm, in fourth gear, or to scream down the road making buzz-saw noises. The power peak is at 6500 rpm, and the makers recommend that no more than 6800 rpm be used, but the power does not really drop away until well past the 7000 rpm level. Valve float occurs at just under 8000 rpm.

Taken strictly as a piece of design work, there is no reason why this engine, which is decidely long of stroke, should accept so much punishment with so little protest. It has the same general lower-end layout as most other vertical twins, and the valve gear — actuated by a single camshaft on the exhaust side of the engine — is a bit more heavy than, for example, the Triumph. However, one cannot “see” such things as careful selection of metals, and only the indisputable fact that the engine does do the job shows that all of the unseen things have been given proper attention. Polished cases are fine, but we are always delighted to find evidence that mechanical beauty has been carried more than just skin-deep, as in the Norton.

Among the general features of the engine are the dual Amal Monobloc carburetors, which have a float only on the left-hand instrument (a feed-line takes fuel to the narrow, floatless chamber on the right-hand carburetor). This makes the engine idle very raggedly if the machine is leaned over on its side when standing still, but it is of no consequence when in motion, and a great deal of space is saved. No air cleaner was fitted on our test machine; but we understand that this is not true of every Atlas. This is, in our opinion, a questionable omission, but one that the buyer can remedy at little cost in time or money.

Ignition is by means of a Lucas magento, installed in such a way that it can be inspected, serviced or removed with a minimum of struggle. No manual control is supplied or required; an automatic advance (of the centrifugal type) is built-in, and it does the job better than 90-percent of the riders we know (and that includes our tech, ed., who is supposed to know just what every little engine sound means). Not the least of the benefits that comes with a good automatic advance mechanism is backrap-free starting, and with a big displacement engine, that can save a lot of trouble.

The lighting draws its current from a battery, which is supplied by an alternator on the output end of the crankshaft. We had no opportunity to put the electrical system to the test — beyond simply using the lights whenever we found ourselves out and about at night — but we assume that it will function at the same high level of efficiency as the rest of the machine.

Some of the miscellaneous engine features are worth a mention: the valves are closed by multi-rate springs, which, in part, accounts for the engine’s ability to crank off those revolutions; and the crankshaft bearing arrangement — roller on the drive end, ball on the timing end — that with the very sturdy crankshaft, contribute so much to reliability. Also, there is the patented layout of the cylinder head: the valves are skewed around so that the exhausts are widely separated and the intakes close together. This permits a good flow of cooling air down past the exhaust and around the middle of the cylinder head. And, because

the intake ports are set parallel, the mixture comes into the combustion chamber tangentially, imparting a swirl that aids combustion immeasurably.

The transmission is mounted separately, a scheme that seems to be out of fashion these days but works well when the transmission has been sufficiently rigidly mounted, as it has been on the Norton. Ratio staging in this transmission may appear a bit uneven, as evidenced by the spacing of the lines on the RPM/MPH graph, but they are well chosen for the Norton’s overall performance characteristics. On a machine as fast as the Atlas, wind resistance becomes a pronounced factor in the upper speed ranges, and the closer spacing of the top two gears enables the rider to keep the engine turning fairly near its peaking speed when air-drag is at its highest. First gear, with so much power on tap, need not be a “stump-puller,” and it isn’t. Using a reasonably safe 7400 rpm, the Atlas can be bounced up to 50 mph without abandoning first gear, and that is a bit of business that really gives the blind staggers to riders of lesser machines. And, too, it is quite possible to “do a wheelie” when you catch second, and that is rather impressive for all concerned — especially the rider of the Atlas.

All of the propelling machinery is hung in an adaptation of Norton’s famous “Featherbed” racing frame. This is a two-loop frame, with tubular outriggers for the rear spring/damper unit mountings and sheet-steel reinforcing where necessary. Of course, it uses Norton’s “road-holder” forks, and the ubiquitous swing-arm type rear suspension.

Braking is provided by the same units (8-inch drums at the front, 7-inch drums at the rear) used on the Manxman. These brakes were entirely equal to the performance of the Manxman; they are marginal on the Atlas. Apparently, the slight increase in performance has caught up to the braking capacity, because we noticed that when used repeatedly, and hard, during a sprint through the mountains, the brakes began to show signs of distress. No outright fading occured, but when pre-warmed by frequent application and then asked to pull the bike down from high speeds, the brakes would shudder just enough to tell us that the limit was near at hand. Obviously, the slightly more restrained use these brakes would get normally would not bring one so near the limit.

On that same trip through the mountains, we renewed our acquaintance with the Norton’s incredible road-holding. On a machine with this kind of stability and roadgrip, the rider may treat a winding, secondary road as though it were a turnpike, and hold a steady 60-70 mph cruising speed. Only the most expert of experts will ever get the Norton near its limit through a fast bend; frankly, our knees turned to water well before the Norton developed any sign of that curious oozing of the bike that tells the rider he’s entering the bandage and liniment stage of the game. At the level of cornering the average rider will maintain, the Atlas may be accelerated or braked a surprising amount without the development of anything more serious than a slight change of course. We cannot say too much for the overall road behavior of this big machine.

The overall gearing gives a compromise between top speed, strain-free cruising and acceleration, and the Atlas is a bit handicapped at the drag strip, but it accelerates at a rate that needs no apology. The standing-quarter figures have been beaten by other machines we have tested, but not by enough to have any special significance. It should be apparent, too, that as the Atlas is using only first, second and a piece of third to get through the quarter, more could easily be wrung from the bike by changing the overall gearing.

The performance trials with the Atlas turned up one curious defect: the seat is too smooth. A rather slick vinyl plastic is used on the seat, and one’s hindside simply does not get enough of a grip for a bike of the Atlas’s potential. This was particularly noticeable on our highspeed runs; we usually follow the procedure of holding the throttle with one hand, and tucking the other arm in close, out of the airstream. At the Norton’s top of just short of 120 mph, the airblast tries to slide the rider off, and the seat doesn’t do much to stop it. The Atlas buyer who likes to do a bit of racing will want to invest in a turned-up-at-the-stern competition saddle.

Apart from the slithery saddle, the Atlas rider should have no complaint. The engine has slathers of torque over a wide speed range and will rev like fury, too. If he doesn’t feel like shifting gears, he won’t have to; all that torque is approximately the equivalent of an automatic transmission. Should he feel like shifting, he will find the Norton’s shift action to be everything one could ask. This is one bike on which we never missed a shift, and neutral (often so elusive) is easily located even by the clumsiest of toes. All controls are nicely located and, our test Atlas was supplied with wide, low and flat bars. Though these bars are not as nice as the original bars installed in England, we liked them much better than the high “western” style bars as standard Atlas’s are equipped. McLaughlin Mtrs. in Duarte, Calif., supplied and prepared out test machine and had changed the original bars.

Starting was generally easy. When we first rode the Atlas, it was very new and stiff, and it gave us a little trouble but that soon passed. Naturally, when a big engine like this is cold and and oil is gluey, it takes a lot of pressure to run it through quickly, but that was the only problem we encountered.

Norton’s Atlas is a motorcycle we would recommend to almost anyone. We say “almost” because we honestly do not think that a beginner, whatever his age and aptitude, has any business on a bike with such tremendous performance. It the beginner would exercise restraint until he had acquired the necessary experience, the Atlas would be fine; few, if any, would.

On the other hand, we cannot think of a better motorcycle for the experienced rider. The Atlas’s big engine gives it that sudden yank down the road that most of us like, and it is geared to give high cruising speeds and high reliability for those long tours. This is one of the few road machines having the kind of performance that will push one’s navel back against one’s backbone; if that sort of thing appeals to you (and we like it), try the Atlas for certain. •

NORTON

750 ATLAS

$1124

SPECIFICATIONS

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

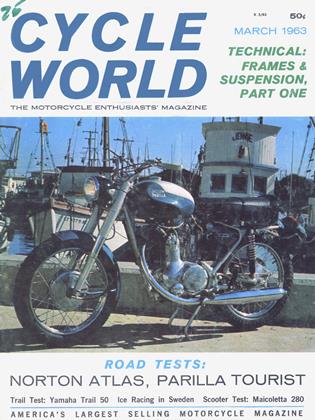

Cycle Round Up

March 1963 By Joseph C. Parkhurst -

The Service Department

March 1963 By Gordon H. Jennings -

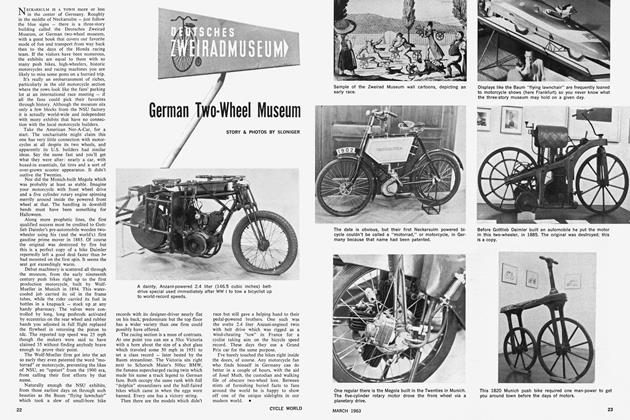

German Two-Wheel Museum

March 1963 By Sloniger -

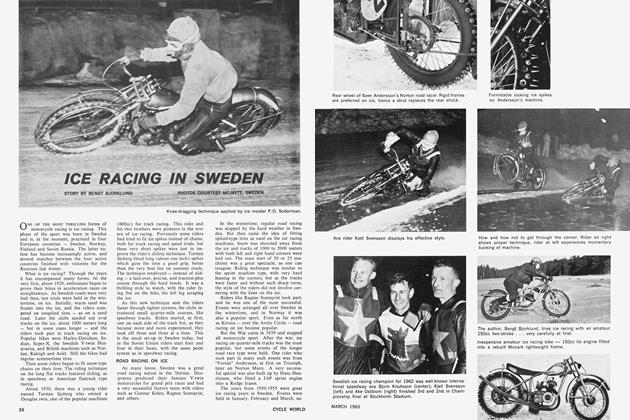

Ice Racing In Sweden

March 1963 By Bengt Bjorklund -

Trail Test

Trail TestYamaha Omaha Trail

March 1963 -

Technical

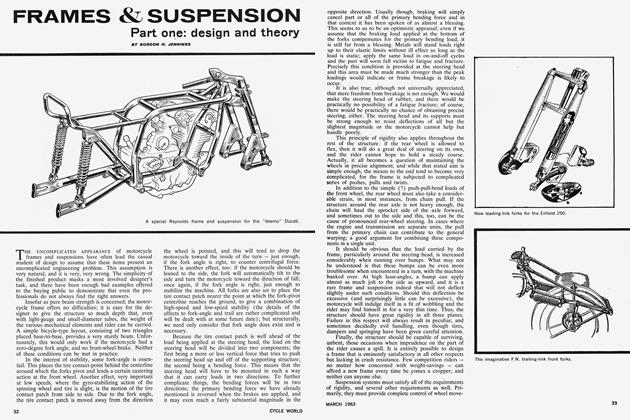

TechnicalFrames & Suspension

March 1963 By Gordon H. Jennings