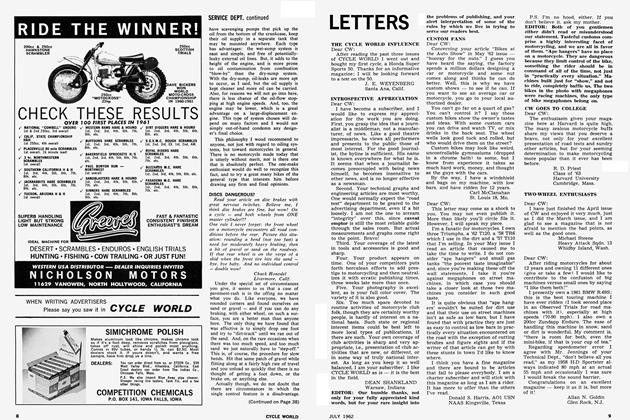

JAWA 250

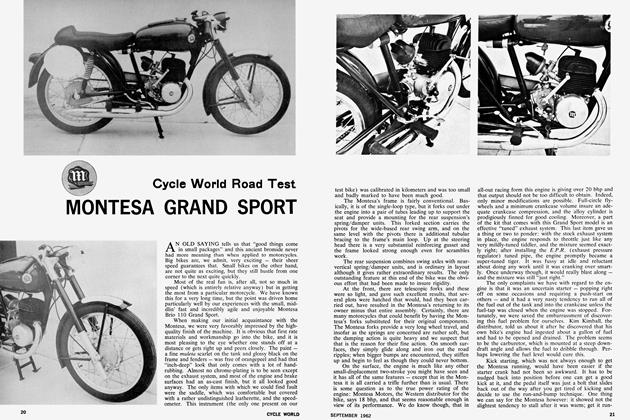

Cycle World Road Test

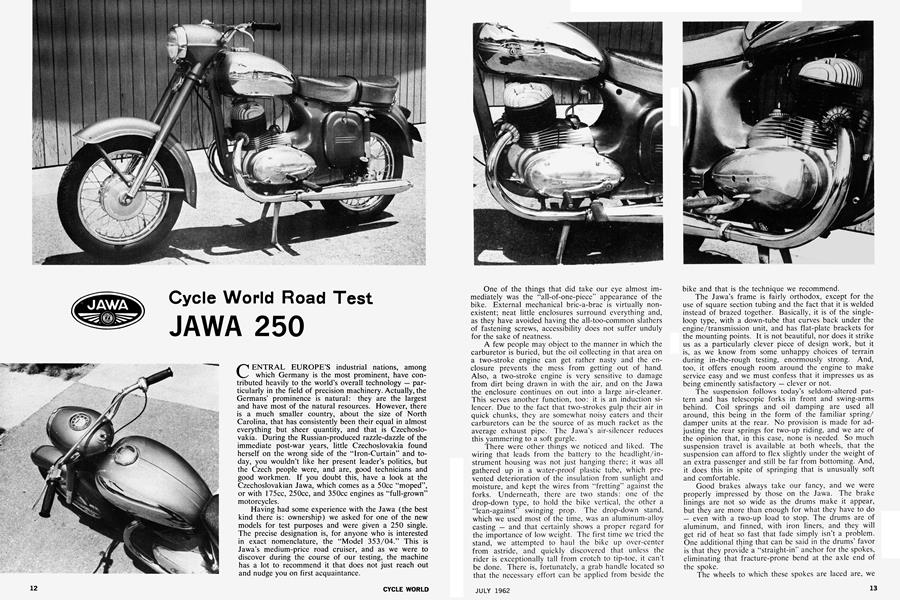

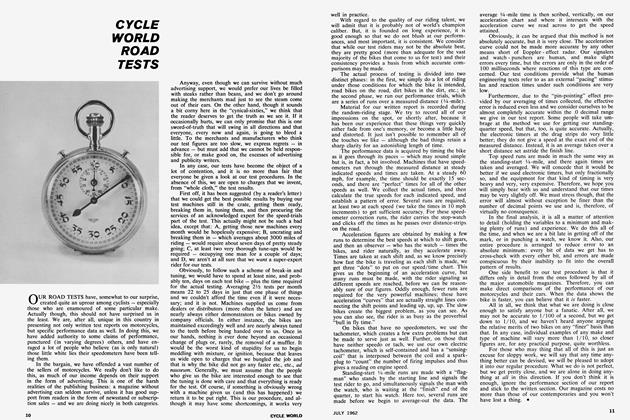

CENTRAL EUROPE’S industrial nations, among which Germany is the most prominent, have contributed heavily to the world’s overall technology — particularly in the field of precision machinery. Actually, the Germans’ prominence is natural: they are the largest and have most of the natural resources. However, there is a much smaller country, about the size of North Carolina, that has consistently been their equal in almost everything but sheer quantity, and that is Czechoslovakia. During the Russian-produced razzle-dazzle of the immediate post-war years, little Czechoslovakia found herself on the wrong side of the “Iron-Curtain” and today, you wouldn’t like her present leader’s politics, but the Czech people were, and are, good technicians and good workmen. If you doubt this, have a look at the Czechoslovakian Jawa, which comes as a 50cc “moped”, or with 175cc, 250cc, and 350cc engines as “full-grown” motorcycles.

Having had some experience with the Jawa (the best kind there is: ownership) we asked for one of the new models for test purposes and were given a 250 single. The precise designation is, for anyone who is interested in exact nomenclature, the “Model 353/04.” This is Jawa’s medium-price road cruiser, and as we were to discover during the course of our testing, the machine has a lot to recommend it that does not just reach out and nudge you on first acquaintance.

One of the things that did take our eye almost immediately was the “all-of-one-piece” appearance of the bike. External mechanical bric-a-brac is virtually nonexistent; neat little enclosures surround everything and, as they have avoided having the all-too-common slathers of fastening screws, accessibility does not suffer unduly for the sake of neatness.

A few people may object to the manner in which the carburetor is buried, but the oil collecting in that area on a two-stroke engine can get rather nasty and the enclosure prevents the mess from getting out of hand. Also, a two-stroke engine is very sensitive to damage from dirt being drawn in with the air, and on the Jawa the enclosure continues on out into a large air-cleaner. This serves another function, too: it is an induction silencer. Due to the fact that two-strokes gulp their air in quick chunks, they are somewhat noisy eaters and their carburetors can be the source of as much racket as the average exhaust pipe. The Jawa’s air-silencer reduces this yammering to a soft gurgle.

There were other things we noticed and liked. The wiring that leads from the battery to the headlight/instrument housing was not just hanging there; it was all gathered up in a water-proof plastic tube, which prevented deterioration of the insulation from sunlight and moisture, and kept the wires from “fretting” against the forks. Underneath, there are two stands: one of the drop-down type, to hold the bike vertical, the other a “lean-against” swinging prop. The drop-down stand, which we used most of the time, was an aluminum-alloy casting — and that certainly shows a proper regard for the importance of low weight. The first time we tried the stand, we attempted to haul the bike up over-center from astride, and quickly discovered that unless the rider is exceptionally tall from crotch to tip-toe, it can't be done. There is, fortunately, a grab handle located so that the necessary effort can be applied from beside the bike and that is the technique we recommend.

The Jawa’s frame is fairly orthodox, except for the use of square section tubing and the fact that it is welded instead of brazed together. Basically, it is of the singleloop type, with a down-tube that curves back under the engine/transmission unit, and has flat-plate brackets for the mounting points. It is not beautiful, nor does it strike us as a particularly clever piece of design work, but it is, as we know from some unhappy choices of terrain during in-the-rough testing, enormously strong. And, too, it offers enough room around the engine to make service easy and we must confess that it impresses us as being eminently satisfactory — clever or not.

The suspension follows today’s seldom-altered pattern and has telescopic forks in front and swing-arms behind. Coil springs and oil damping are used all around, this being in the form of the familiar spring/ damper units at the rear. No provision is made for adjusting the rear springs for two-up riding, and we are of the opinion that, in this case, none is needed. So much suspension travel is available at both wheels, that the suspension can afford to flex slightly under the weight of an extra passenger and still be far from bottoming. And, it does this in spite of springing that is unusually soft and comfortable.

Good brakes always take our fancy, and we were properly impressed by those on the Jawa. The brake linings are not so wide as the drums make it appear, but they are more than enough for what they have to do — even with a two-up load to stop. The drums are of aluminum, and finned, with iron liners, and they will get rid of heat so fast that fade simply isn’t a problem. One additional thing that can be said in the drums' favor is that they provide a “straight-in” anchor for the spokes, eliminating that fracture-prone bend at the axle end of the spoke.

The wheels to which these spokes are laced are, we might mention, somewhat smaller in diameter than those to which we have been accustomed, but that is, we understand, done to allow room for the large suspension movements we mentioned earlier. These movements require room above the wheels, and small wheels are the only thing that will turn the trick if excessive overall height is to be avoided.

The engine and transmission are all in a unit, with an extension on the rear of the sealed-off crankcase housing the gears and the shift mechanism. The transmission is of the cross-over type, and as we noted on the Maico, it loads its bearings a bit more than the co-axial variety in which the drive enters and emerges on the same side. On the other hand, it does simplify the swapping of drive sprockets and there is something to be said for that.

An especially clever touch on the transmission was the arrangement of the shift-lever. This is another double-duty item on the Jawa; it is a foot-shift lever, and by pushing it inward, you disengage the shifting mechanism and then the pedal is free to be swung back and into position for use as a kick starter. The idea may sound a bit peculiar, but we quickly learned to like it. Oddly enough, the cleverness of the starter layout does not stop there. It is geared so that it drives the engine through the primary chain without passing through the clutch. This means that if you stall the bike, it isn’t necessary to find neutral before re-starting; just disengage the clutch and give it a kick.

The Jawa’s engine is no less appealing than its transmission. It is a single, with a rather longish stroke, but it is smoother than almost anything. The port timing is apparently quite conservative, as it shows none of the “5000 rpm and then gangbusters” characteristics of the highly-tuned two-stroke. Instead, it pulls strongly and smoothly from very low speeds and you can use highgear-only tactics even in traffic.

Anyone who is more interested in speed than in smoothness will be pleased to know that this is an engine that fairly begs to be modified. The inlet, exhaust and transfer ports are of sufficient size to allow modified timing and higher operating speeds, and the engine certainly seems strong enough to take the strain. Furthermore, the transfer passages, which are usually so small and hard to get at, are very large and as they are located partly in the cylinder and partly in the crankcase, reworking them would be pure fun. Finally, even people who really don't know exactly how to do the job need have no qualms about attempting quite extensive modifications on the Jawa. There is a small handbook, available from Jawa (in English, too) that gives step-by-step instructions for the entire procedure.

Actually, the Jawa has, even in its stock form, enough power to satisfy most riders — and it would be a shame to lose any of that lovely smoothness. As our performance figures show, the bike is no drag-strip commando, but bare acceleration times do not tell the entire story. The impressive thing about the Jawa is that it pulls so strongly without being twisted over very fast. This helps a lot in making it the pleasant and comfortable touring machine it is.

Another thing that helps is its easy-start characteristics. At no time during our entire test did it ever require more than two kicks — and usually only one. When cold, you just “tickle” the carburetor float a bit, run it through once to get a charge into the cylinder, and the next kick will have it running. And, once started, it will sit and idle, making soft “pocka-pocka” noises while the rider stamps his feet, yawns, scratches himself and gets ready to tackle the morning traffic on his way to work.

His trip will be eased by the Jawa’s handling, which we would rate as terribly good for a softly-suspended “roadster,” and by such features as a nice, wide, “form” fitting seat. Also, there is no-clutch shifting (a camplate shoves the clutch out of engagement when pressure is applied at the gear lever). And, when those inevitable moments of roadside repair occur, he will find that the Czechs have thoughtfully provided a well-fitted tool kit. This Jawa is, as we had remembered it, a very nice touring motorcycle.

JAWA 250

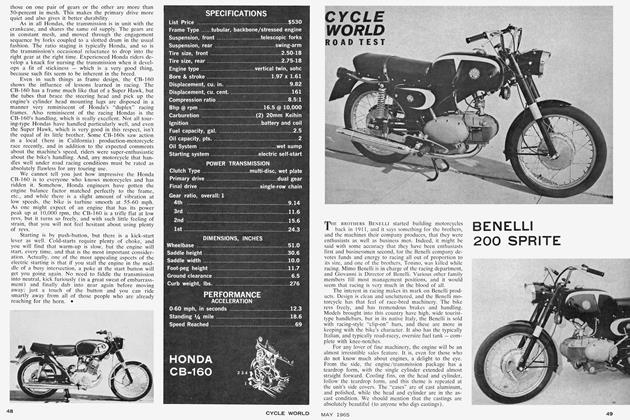

SPECIFICATIONS

$499.00