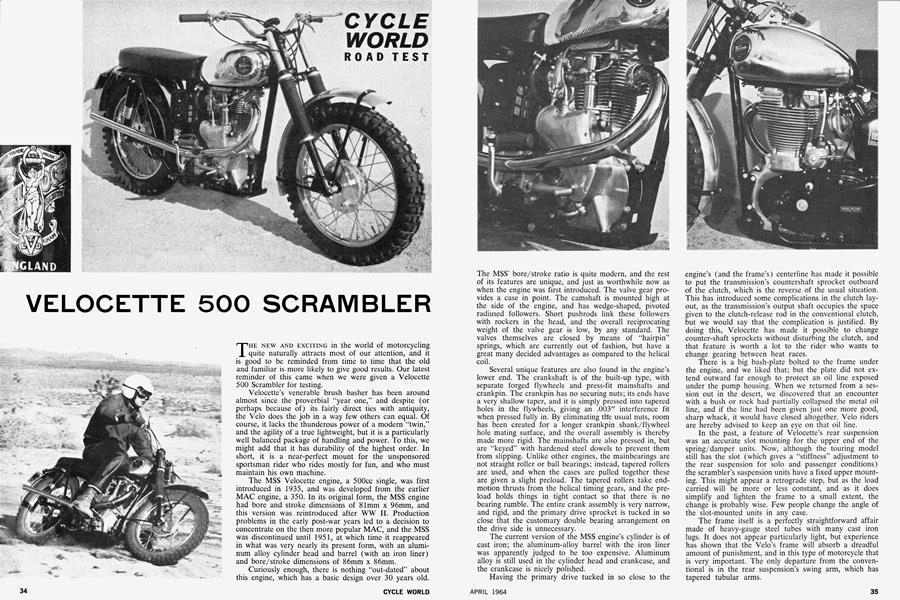

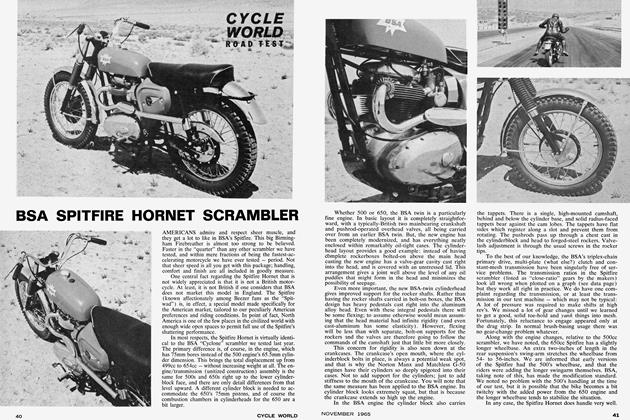

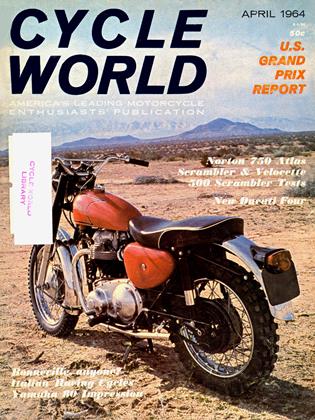

VELOCETTE 500 SCRAMBLER

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

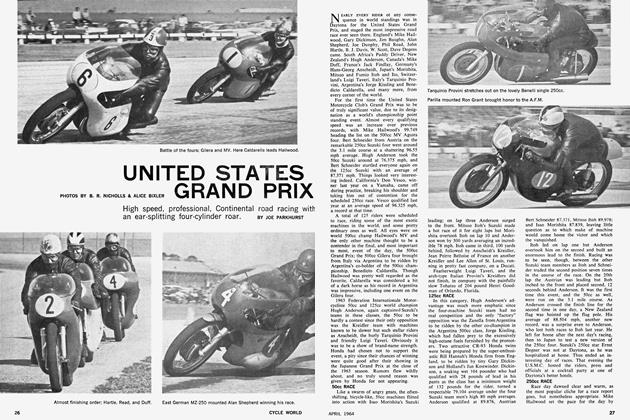

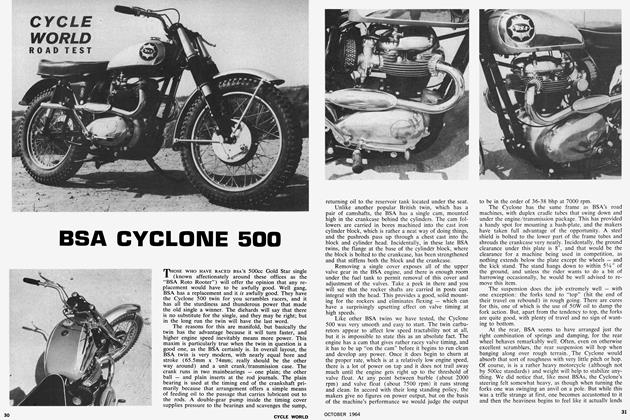

THE NEW AND EXCITING in the world of motorcycling quite naturally attracts most of our attention, and it is good to be reminded from time to time that the old and familiar is more likely to give good results. Our latest reminder of this came when we were given a Velocette 500 Scrambler for testing.

Velocette's venerable brush basher has been around almost since the proverbial "year one," and despite (or perhaps because of) its fairly direct ties with antiquity, the Velo does the job in a way few others can equal. Of course, it lacks the thunderous power of a modern "twin," and the agility of a true lightweight, but it is a particularly well balanced package of handling and power. To this, we might add that it has durability of the highest order. In short, it is a near-perfect mount for the unsponsored sportsman rider who rides mostly for fun, and who must maintain his own machine.

The MSS Velocette engine, a 500cc single, was first introduced in 1935, and was developed from the earlier MAC engine, a 350. In its original form, the MSS engine had bore and stroke dimensions of 81mm x 96mm, and this version was reintroduced after WW II. Production problems in the early post-war years led to a decision to concentrate on the then more popular MAC, and the MSS was discontinued until 1951, at which time it reappeared in what was very nearly its present form, with an aluminum alloy cylinder head and barrel (with an iron liner) and bore/stroke dimensions of 86mm x 86mm.

Curiously enough, there is nothing "out-dated" about this engine, which has a basic design over 30 years old. The MSS' bore/stroke ratio is quite modern, and the rest of its features are unique, and just as worthwhile now as when the engine was first introduced. The valve gear provides a case in point. The camshaft is mounted high at the side of the engine, and has wedge-shaped, pivoted radiused followers. Short pushrods link these followers with rockers in the head, and the overall reciprocating weight of the valve gear is low, by any standard. The valves themselves are closed by means of "hairpin" springs, which are currently out of fashion, but have a great many decided advantages as compared to the helical coil.

Several unique features are also found in the engine's lower end. The crankshaft is of the built-up type, with separate forged flywheels and press-fit mainshafts and crankpin. The crankpin has no securing nuts; its ends have a very shallow taper, and it is simply pressed into tapered holes in the flywheels, giving an .003" interference fit when pressed fully in. By eliminating the usual nuts, room has been created for a longer crankpin shank/flywheel hole mating surface, and the overall assembly is thereby made more rigid. The mainshafts are also pressed in, but are "keyed" with hardened steel dowels to prevent them from slipping. Unlike other engines, the mainbearings are not straight roller or ball bearings; instead, tapered rollers are used, and when the cases are pulled together these are given a slight preload. The tapered rollers take endmotion thrusts from the helical timing gears, and the preload holds things in tight contact so that there is no bearing rumble. The entire crank assembly is very narrow, and rigid, and the primary drive sprocket is tucked in so close that the customary double bearing arrangement on the drive side is unnecessary.

The current version of the MSS engine's cylinder is of cast iron; the aluminum-alloy barrel with the iron liner was apparently judged to be too expensive. Aluminum alloy is still used in the cylinder head and crankcase, and the crankcase is nicely polished.

Having the primary drive tucked in so close to the engine's (and the frame's) centerline has made it possible to put the transmission's countershaft sprocket outboard of the clutch, which is the reverse of the usual situation. This has introduced some complications in the clutch layout, as the transmission's output shaft occupies the space given to the clutch-release rod in the conventional clutch, but we would say that the complication is justified. By doing this, Velocette has made it possible to change counter-shaft sprockets without disturbing the clutch, and that feature is worth a lot to the rider who wants to change gearing between heat races.

There is a big bash-plate bolted to the frame under the engine, and we liked that; but the plate did not extend outward far enough to protect an oil line exposed under the pump housing. When we returned from a session out in the desert, we discovered that an encounter with a bush or rock had partially collapsed the metal oil line, and if the line had been given just one more good, sharp whack, it would have closed altogether. Velo riders are hereby advised to keep an eye on that oil line.

In the past, a feature of Velocette's rear suspension was an accurate slot mounting for the upper end of the spring/damper units. Now, although the touring model still has the slot (which gives a "stiffness" adjustment to the rear suspension for solo and passenger conditions) the scrambler's suspension units have a fixed upper mounting. This might appear a retrograde step, but as the load carried will be more or less constant, and as it does simplify and lighten the frame to a small extent, the change is probably wise. Few people change the angle of the slot-mounted units in any case.

The frame itself is a perfectly straightforward affair made of heavy-gauge steel tubes with many cast iron lugs. It does not appear particularly light, but experience has shown that the Velo's frame will absorb a dreadful amount of punishment, and in this type of motorcycle that is very important. The only departure from the conventional is in the rear suspension's swing arm, which has tapered tubular arms.

One of the several things we liked about the Velocette was that it is a compact package. The wheelbase is fairly long, but the bike is low and light, with a low center of gravity. The rider will actually tend to think it is smaller than is really the case; partly because the Velo is low; and partly because it handles more like a lightweight than a 500 — which is all to the good. So far as we could determine, the lowness has only one bad effect: the fuel tank is dropped down so that it shrouds the cylinder head, and it would be all but impossible to even adjust the valvelash without first removing the tank.

Perhaps because it is low, and because it is well finished, the Velo is a fine-looking machine. The tank is chromed, with a large black panel up the middle and a gold pin stripe. Fenders are of polished aluminum alloy, and the frame is black-enameled. Most of the exposed surfaces of the machinery are either buffed to a high polish or chrome plated. The only item we did not particularly like was the primary drive case, which is a black-enameled steel pressing. This does not look nearly so elegant as would polished aluminum, and it seems to us that this case could be dented rather badly in one of the falls that inevitably occur.

Mixed opinions were delivered on the Velo's seat. It was agreed that for size, contour and placement, the seat was perfect. However, most of the staff members who rode the machine held the opinion that it was too hard. It may be that the seat is all right and they are too soft.

All were agreed that the handlebars were too low and too far forward. Our taller riders did not really object to the bars, but conceded that they would be better if bent up and back a couple of inches; the shorter people on the staff rated this modification as essential.

Ball-end control levers are provided, but there are no adjusters for the cables at the levers; all adjustments have to be made at the other end of the cable, which is a great deal less convenient. The foot pegs were made of heavy steel strap, with ends bent upward to provide a good grip. Unfortunately, the left peg is a bit short, and most of us would prefer a folding peg. Bellows-type dust covers are fitted on the fork legs, and this feature we liked very much. We also liked the extremely sturdy rear fender brace, which was really an extension of the frame and strong enough to be used to hoist the entire motorcycle.

There was no stand of any kind, which will not really distress the competition rider, and no tachometer, which would be rather welcome, as the engine must be twisted up fairly tight before the power comes on strong. The engine is equipped with a long straight-pipe, and there is no problem with "megaphonitis," but the cams and carburetion are such that it is really happy only when running at relatively high speeds. In England, the Velocette Scrambler is sold with a TT-pattern carburetor; those imported to this country have a touring-type Amal Monobloc.

A very large air cleaner is fitted, but it is of the gravelstrainer variety, and of limited effectiveness in dealing with fine dust — although it is certainly better than nothing. An oil filter is built into the oil tank, and may be removed for cleaning or replacement simply by taking off a one-bolt circular cover.

In general, all of the points that might require service are easily reached. The adjustments for setting tension at the primary chain are nicely within wrench-reach, and the sundry small plugs and covers are likewise. The only thing that was hidden away was, rather surprisingly, the carburetor-float tickler, which was up near the fuel tank in the middle of the frame.

Some practice was required before we became proficient at cranking off the Velo. Big singles do not usually come to life any too willingly in any case, and the Velocette's starter drive ratio is far, far from anything we would choose. The bike requires a quick run-through to start, and the starter gearing does not give that kind of spin to the engine unless the rider's foot comes down faster than a speeding bullet, and as powerfully as a locomotive. If you can get it right the first time, you can probably also leap tall buildings at a single bound.

When riding the Velocette Scrambler out across our favorite patch of desert, we discovered that it is a better scrambler than a cross-country bike. The suspension is a bit too stiff for really rough going, and there are times when it tends to pitch a bit. On the other hand, when the ground is reasonably smooth, the Velo really comes into its own. With its low build, and stiff, controllable suspension, it fairly begs to be flung about in fast power-slides, and it slides with the same ease and controllability as a well balanced flat-track racing bike. In other words, the Velocette is just right for the sort of high-speed scrambles that are so popular these days. And, of course, even though it is not the best cross-country bike we have ever tried, it is still extremely good — and it will do things that would cause a good cross-country bike to pitch its rider right off on his head.

As we have said, compared to one of the hotter twins, the Velocette is a bit down on power. But, this can be helped somewhat by increasing the compression a point or so to take advantage of the better fuel available in service stations around this country, and the TTpattern carburetor used on the English version of the bike would also help. And obviously, even in perfectly standard, showroom trim the Velocette is powerful enough to get right up there and tussle with everyone but the hottest of the hot-dogs. When all is said and done, if the rider of a Velocette does not see his name somewhere in the win-place-show listing, he cannot in fairness blame the machine; it has most of what it takes and the rest can be added without too much trouble or expense. •

VELOCETTE 500 SCRAMBLER

SPECIFICATIONS

$960.00

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue