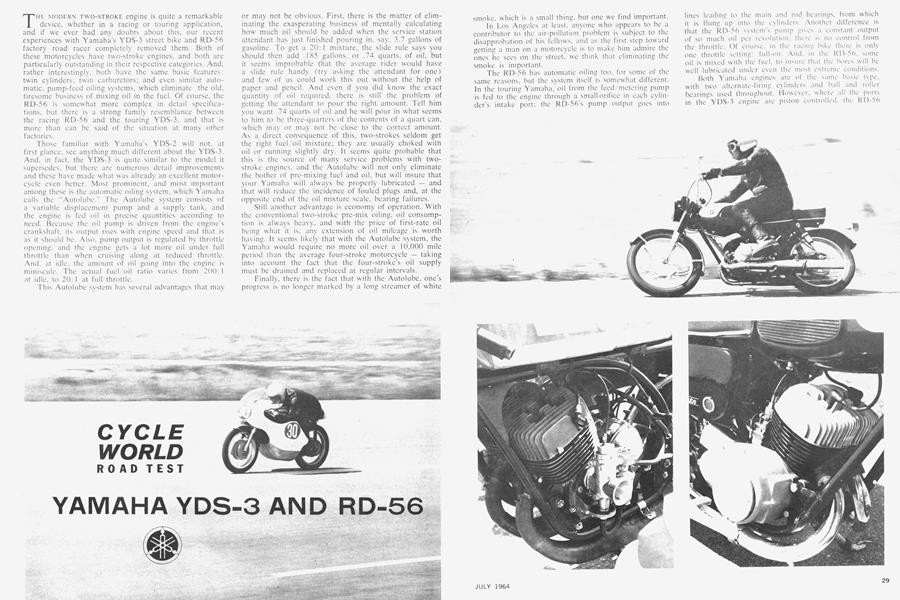

YAMAHA YDS-3 AND RD-56

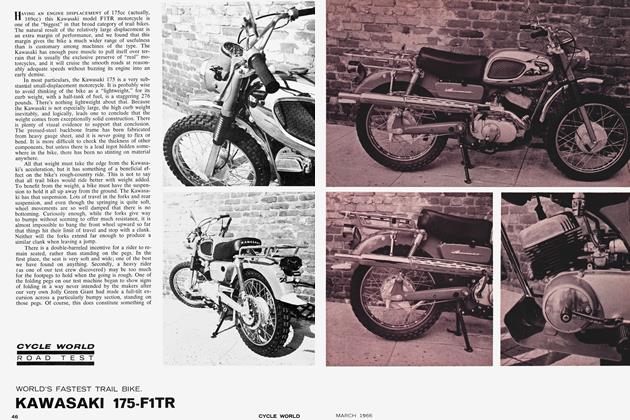

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

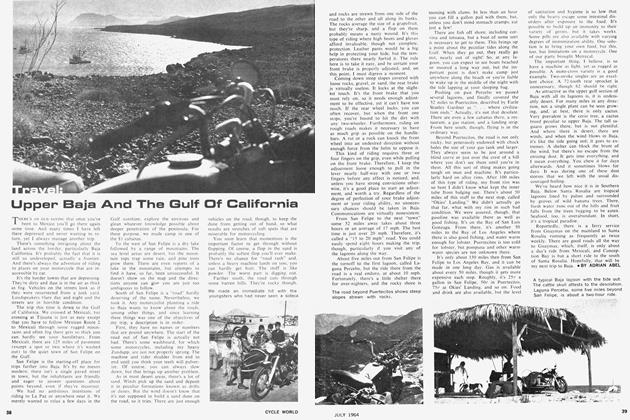

THE MODERN TWO-STROKE engine is quite a remarkable device, whether in a racing or touring application, and if we ever had any doubts about this, our recent experiences with Yamaha's YDS-3 street bike and RD-56 factory road racer completely removed them. Both of these motorcycles have two-stroke engines, and both are particularly outstanding in their respective categories. And, rather interestingly, both have the same basic features: twin cylinders; twin carburetors; and even similar automatic, pump-feed oiling systems, which eliminate the old, tiresome business of mixing oil in the fuel. Of course, the RD-56 is somewhat more complex in detail specifications, but there is a strong family resemblance between the racing RD-56 and the touring YDS-3, and that is more than can be said of the situation at many other factories.

Those familiar with Yamaha's YDS-2 will not. at first glance, see anything much different about the YDS-3. And, in fact, the YDS-3 is quite similar to the model it supersedes, but there are numerous detail improvements and these have made what was already an excellent motorcycle even better. Most prominent, and most important among these is the automatic oiling system, which Yamaha calls the “Autolube." The Autolube system consists of a variable displacement pump and a supply tank, and the engine is fed oil in precise quantities according to need. Because the oil pump is driven from the engine’s crankshaft, its output rises with engine speed and that is as it should be. Also, pump output is regulated by throttle opening, and the engine gets a lot more oil under full throttle than when cruising along at reduced throttle. And. at idle, the amount of oil going into the engine is miniscule. The actual fuel/oil ratio varies from 200: 1 at idle, to 20:1 at full throttle.

This Autolube system has several advantages that may or may not be obvious. First, there is the matter of eliminating the exasperating business of mentally calculating how much oil should be added when the service station attendant has just finished pouring in, say, 3.7 gallons of gasoline. To get a 20:1 mixture, the slide rule says you should then add .185 gallons, or .74 quarts, of oil, but it seems improbable that the average rider would have a slide rule handy (try asking the attendant for one) and few of us could work this out without the help of paper and pencil. And even if you did know' the exact quantity of oil required, there is still the problem of getting the attendant to pour the right amount. Tell him you want .74 quarts of oil and he will pour in what seems to him to be three-quarters of the contents of a quart can, which may or may not be close to the correct amount. As a direct consequence of this, two-strokes seldom get the right fucl/oil mixture; they are usually choked with oil or running slightly dry. It seems quite probable that this is the source of many service problems with twostroke engines, and the Autolube will not only eliminate the bother of pre-mixing fuel and oil. but will insure that your Yamaha will always be properly lubricated — and that will reduce the incidence of fouled plugs and, at the opposite end of the oil mixture scale, bearing failures.

Still another advantage is economy of operation. With the conventional two-stroke pre-mix oiling, oil consumption is always heavy, and with the price of first-rate oil being what it is. any extension of oil mileage is worth having. It seems likely that with the Autolube system, the Yamaha would require no more oil over a 10,000 mile period than the average four-stroke motorcycle — taking into account the fact that the four-stroke's oil supply must be drained and replaced at regular intervals.

Finally, there is the fact that with the Autolube, one’s progress is no longer marked by a long streamer of white smoke, which is a small thing, but one we find important.

In Los Angeles at least, anyone who appears to be a contributor to "the air-pollution problem is subject to the disapprobation of his fellows, and as the first step toward getting a man on a motorcycle is to make him admire the ones he sees on the street, we think that eliminating the smoke is important.

The RD-56 has automatic oiling too, for some of the same reasons, but the system itself is somewhat different. In the touring Yamaha, oil from the feed/metering pump is fed to the engine through a small orifice in each cylinder's intake port; the RD-56's pump output goes into lines leading to the main and rod bearings, from which it is flung up into the cylinders. Another difference is that the RD-56 system's pump gives a constant output of so much oil per revolution; there is no control from the throttle. Of course, in the racing bike there is only one throttle setting: full-on. And. in the RD-56, some oil is mixed with the fuel, to insure that the bores will be well lubricated under even the most extreme conditions.

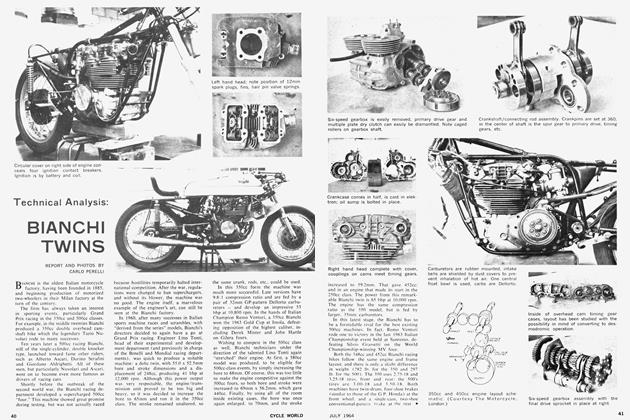

Both Yamaha engines are ot the same basic type, with two alternate-firing cylinders and ball and roller bearings used throughout. However, where all the ports in the YDS-3 engine are piston controlled, the RD-56 engine has disc-type rotary intake porting. Also, the cylinders in the RD-56 are all-aluminum, with hardanodized bores, while those of the YDS-3 arc of the wearresistant alloy iron. In the YDS-3 engine, the back of the cylinder is used for the piston-controlled intake port, but in the RD-56 this space is filled with an extra pair of transfer ports, in addition to the usual transfer ports at the sides of the bore. Thus, a maximum of the cylinder diameter is taken up in port area, which is essential in a high-speed two-stroke engine. We might mention, just for the enlightenment of you two-stroke fanciers, that the side transfer ports aim into the cylinder almost straight across, while the extra pair of transfer ports at the rear of the cylinder are angled up at about 60-degrces.

The RD-56 engine wears a pair of “Amal-pattern" (Yamaha’s term) carburetors with throats 1 % " in diameter. These are, obviously, really huge for cylinders that displace only 125cc each, but the engine develops 51 bhp at 10,500 rpm, and it takes big carburetors to flow enough mixture for 51 horsepower. The engine employs a rather interesting ignition system: there is an alternator running at half engine speed, with two sets of points and a double-lobe breaker cam, and this assembly generates and controls low-tension current for a pair of hightension coils. The reason for running the alternator at half engine speed is for reliability. At full engine speed, the unit would be twirling around at speeds up to 12,000 rpm, and that is a trifle too fast for the health of the bearings and rotating elements.

The very high operating speed of the engine has brought about two rather interesting features of the RD-56 engine that are not related at all. First, there is the manner in which carburetors and float chambers are mounted. Both are insulated against engine vibration. The carburetors are on stubs that have a soft rubber sleeve where they go into the engine, and the float chambers actually dangle from a rubber mounting. These measures are necessary to prevent high-frequency engine vibrations from affecting the carburetion. The engine feels quite smooth to the rider; but then he is not overly sensitive to high-frequency vibration, and the carburetors and float chambers are. The other effect of the high operating speed is related to the extreme narrowing of the power range. The RD-56 engine begins to pull well only when up above 9500 rpm, and one really should change up at 11,000 rpm, which gives a spread of only 1500 rpm. This has necessitated a seven-speed transmission, which means that the rider keeps busy stirring the gears. The transmission is, fortunately, very smooth and easy to shift — and that is a good thing, as getting lost in a neutral somewhere in the middle of 7 speeds is no joke. We were told, before riding the machine, that the transmission is a trifle frail (it is impossible to make the gears very wide when trying to fit 7 pairs of them into a narrow case) and that made us cautious about banging shifts too vigorously.

One need not be the least bit cautious when shifting the YDS-3. In common with the late-series YDS-2, it has extra-wide gear teeth, and as the transmission is really designed to take the pressure from Yamaha's TD-1 production-racer engine, the YDS-3 engine does not load it to anything near the limit of its strength. We arc of the opinion that this transmission is one of the best features of the YDS-3: it has 5 speeds, with well-spaced ratios, and it shifts very smoothly and positively.

The touring Yamahas have their clutch mounted on the end of the crankshaft, running at engine speed, and because there is no torque multiplication between engine and clutch, the clutch can be quite small — and it is. Indeed, in the past there have been indications that it might be a trifle too small, and in the more powerful YDS-3, a fifth clutch plate has been added to carry the increased torque.

Because some trouble has been encountered in the racing version of the YDS-2 engine (the TD-1), the YDS-3 crankshaft has mainshafts a full inch in diameter, up from s/%" in earlier models. Also, the engine’s wrist-pin diameter has been increased from 17mm to 20mm. These changes have been made in the interest of reliability; the carburetors have been increased in size from 20mm to 24mm to give the bike a boost in power.

A few changes have been made in the frame and suspension. The frame is basically identical, but the engine is now mounted on forged lugs, instead of sheet-metal pressings, and the wheelbase has been stretched an inch. The suspension has been given stiffer springs and damping, and the bike corners appreciably better than the YDS-2. The earlier model was a bit too soft, and would surge up and down when cornered hard; the YDS-3 is much steadier, and can be leaned right down until things begin to drag without losing its stability.

The YDS-3 also has a new instrument cluster, with speedo and tach grouped together as before. However, where the earlier speedo and tach were so similar that some confusion was possible, the new instrument cluster is arranged so that one can see at a glance which needle is indicating road speed and which is indicating rpm. There is a warning light that tells the rider if the generator is doing its job and another that flashes on when neutral has been selected. A third is to be added, and this will flash on if, for any reason, the Autolube pump stops feeding oil to the engine. In that unlikely event, the rider simply transfers oil from the supply tank to the main fuel tank and proceeds on a conventional two-stroke fuel/oil mix.

The brakes on the YDS-3 remain as before, which is to say that they are tremendous. The front brake is of the two leading shoe variety, and provides a lot of stopping power for remarkably little effort at the brake lever. The rear brake has leading and trailing shoes, and it too is extremely powerful.

The braking system on the RD-56 is just its impressive. There are actually two brake drums in the from wheel hub, and a total of four brake shoes. The stopping power from this combination has to be tried to be believed. The only thing one might consider to be wrong with the front brake is that too much pressure on the control lever will lock the wheel. Of course, while this constitutes something of a hazard for the clumsy rider, the man who would be riding the Yamaha RD-56 would have sufficient skill to cope with that problem.

Powerful as the brakes were, they were no more than a match for the speed of the RD-56. Even though the bike was fitted with gearing that gave it a top speed of 140 mph. the engine had enough steam to make the front wheel very light when accelerating at full throttle. The power range is quite narrow, but if you keep busy at the 7-speed transmission, the engine will stay “on the pipe" and your progress down the road is something to behold. We were fortunate enough to get the RD-56 out for a run at the drag strip, and the results of that little venture were most gratifying. Don Vesco did the riding, as no one on the staff wanted to risk breaking the transmission, and despite the handicap of a slipping clutch he was able to get off a run of 104 mph. The crowd at the drag strip loved it. They laughed when the RD-56 came crackling up to the line, but when Vesco went blasting off, making shift, after shift, after shift, after shift, after shift, after shift, as he disappeared in the distance, the laughter turned to cheers.

Our big moment of entertainment with the Yamahas was. of course, when we ran them at Riverside Raceway. Mr. T. Naitoh, Yamaha's Chief Design Engineer came out to supervise the proceedings, and was accompanied by “Tony” Nunotani, a Yamaha engineer who also functions as a racing mechanic, and Jim Jingu, Yamaha Advertising Manager. These gentlemen were there to keep the machines in order, and Don Vesco came along to show us how the RD-56 should be ridden. We also had a pair of YDS-3s for testing and general fun.

The RD-56 was just as difficult to ride properly as you might assume it to be. It is necessary to slip the clutch quite a lot while getting underway, and then when the engine does begin to pull, it “comes in” with a really fantastic surge of power. This quickly pulls you up to the limit in first, and you must then dab it into second — after which, just as quickly, you are out of revs in second and must change to third. This process continues in rapid-fire fashion up through the gears and by the time you are ready to slip it into seventh cog, the RD-56 is really moving. Indeed, the only time we could get into 7th was when we used the full “long-course” straightaway; throughout the rest of the circuit, even when going down the very fast “esses,” the lower gears were used.

One of the things that made the RD-56 tricky for us to ride was the ferocious acceleration. One comes away from one bend, turns up the tap (shifting every few seconds ) and arrives at the next bend really flying — which made us appreciate the machine's brakes very much indeed. Our technical editor, who fancies himself a bona fide road racer, nearly got himself into trouble because of the deceptively fast acceleration. He did a few laps, and then full of confidence tried to run full-bore (shift, shift, shift, shift) up the straight from turn 9 to turn 1 — which is a left hander that should be taken at just over 100 mph. To make, a long story short, he went around on the edge of the bend muttering whoops, whoops, whoops, through clenched teeth, and emerged from the turn considerably chastened by the experience. Grand Prix road racing motorcycles are not to be taken lightly.

Apart from the complications introduced by the RD-56's sheer speed, it is a marvelous thing to ride. The stability and cornering are absolutely tops, and while it takes a superb rider to get the most from it, even a comparative duffer can get around a road circuit fairly fast just because the bike gives its rider so much help.

We were pleased to find that it was also possible to get around very quickly on the standard YDS-3s. His Nibs, the publisher, and the technical editor, went out on the pair of YDS-3s and had a private race for many laps, running in close formation with one unable to get away from the other. They report that the YDS-3’s cornering speed is limited only by the lean-angle at which things begin to drag, and they were resorting to slipping 'way over on the seat to get their weight down on the inside of the turns while holding the machines as upright as possible. This was a bit startling, when one considers how far the YDS-3 will lean before it does begin to drag. In all, it must be considered a tribute to the good road manners of the YDS-3 that one or both of our heroes did not scuff their leathers on that day.

Besides the good handling, the YDS-3 offers the touring/sporting rider what is probably the easiest starting of any two-stroke (and most four-strokes) in the world. The carburetors are equipped with mixture-enrichment starting devices (these are not chokes) and to get the engine perking when cold you simply flip these on (a single lever controls both) and run the engine through smartly with the kick starter. Usually on the first kick, the engine will fire, and if it does not, the second or third is sure to do the trick. One thing one should remember, however, is that the starting devices function best when the throttle is closed, and it is best to leave the throttle closed until the engine starts.

The YDS-3 also offers a comfortable riding position, a fine ride in addition to the fine handling, and a quality of finish and construction that is really remarkable. The only thing about the whole machine that we did not like was the center stand, which does the job. but a lot of muscle is required to pull the bike up on the stand. However, this is a piddling complaint, and it seems even more piddling when you consider that the YDS-3 is an exceptionally fast 250 — as fast as some 500s — and that it has everything else a lightweight enthusiast could want.

YAMAHA

YDS3

SPECIFICATIONS

$630

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue