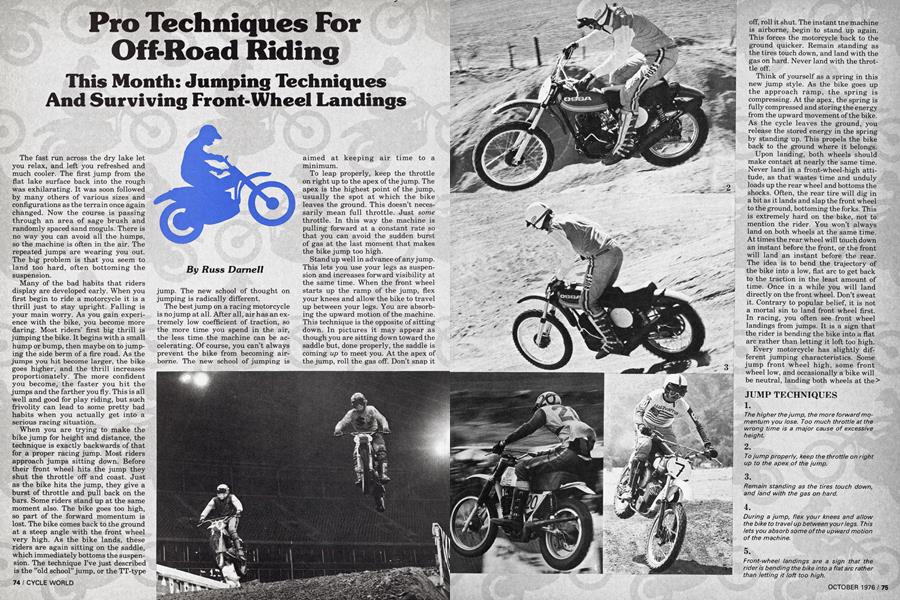

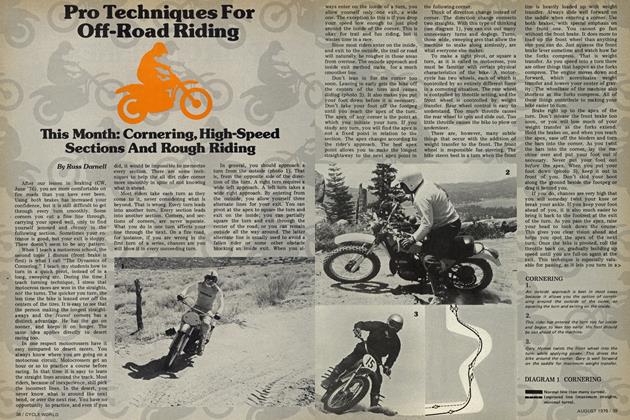

Pro Techniques For Off-Road Riding

This Month: Jumping Techniques And Surviving Front-Wheel Landings

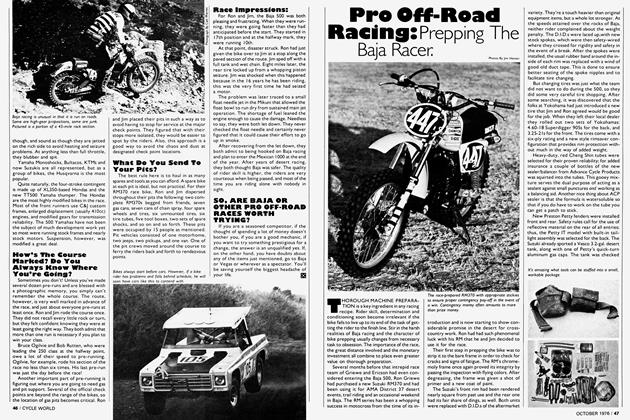

The fast run across the dry lake let you relax, and left you refreshed and much cooler. The first jump from the flat lake surface back into the rough was exhilarating. It was soon followed by many others of various sizes and configurations as the terrain once again changed. Now the course is passing through an area of sage brush and randomly spaced sand moguls. There is no way you can avoid all the humps, so the machine is often in the air. The repeated jumps are wearing you out. The big problem is that you seem to land too hard, often bottoming the suspension.

Many of the bad habits that riders display are developed early. When you first begin to ride a motorcycle it is a thrill just to stay upright. Falling is your main worry. As you gain experience with the bike, you become more daring. Most riders’ first big thrill is jumping the bike. It begins with a small hump or bump, then maybe on to jumping the side berm of a fire road. As the jumps you hit become larger, the bike goes higher, and the thrill increases proportionately. The more confident you become, the faster you hit the jumps and the farther you fly. This is all well and good for play riding, but such frivolity can lead to some pretty bad habits when you actually get into a serious racing situatiôn.

When you are trying to make the bike jump for height and distance, the technique is exactly backwards of that for a proper racing jump. Most riders approach jumps sitting down. Before their front wheel hits the jump they shut the throttle off and coast. Just as the bike hits the jump, they give a burst of throttle and pull back on the bars. Some riders stand up at the same moment also. The bike goes too high, so part of the forward momentum is lost. The bike comes back to the ground at a steep angle with the front wheel very high. As the bike lands, these riders are again sitting on the saddle, which immediately bottoms the suspension. The technique I’ve just described is the "old school” jump, or the TT-type jump. The new school of thought on jumping is radically different.

Russ Darnell

The best jump on a racing motorcycle is no jump at all. After all, air has an extremely low coefficient of traction, so the more time you spend in the air, the less time the machine can be accelerating. Of course, you can’t always prevent the bike from becoming airborne. The new school of jumping is aimed at keeping air time to a inimum.

To leap properly, keep the throttle on right up to the apex of the jump. The apex is the highest point of the jump, usually the spot at which the bike leaves the ground. This doesn’t necessarily mean full throttle. Just some throttle. In this way the machine is pulling forward at a constant rate so that you can avoid the sudden burst of gas at the last moment that makes the bike jump too high.

Stand up well in advance of any jump. This lets you use your legs as suspension and increases forward visibility at the same time. When the front wheel starts up the ramp of the jump, flex your knees and allow the bike to travel up between your legs. You are absorbing the upward motion of the machine. This technique is the opposite of sitting down. In pictures it may appear as though you are sitting down toward the saddle but, done properly, the saddle is coming up to meet you. At the apex of the jump, roll the gas off. Don’t snap it off, roll it shut. The instant tne machine is airborne, begin to stand up again. This forces the motorcycle back to the ground quicker. Remain standing as the tires touch down, and land with the gas on hard. Never land with the throttle off.

Think of yourself as a spring in this new jump style. As the bike goes up the approach ramp, the spring is compressing. At the apex, the spring is fully compressed and storing the energy from the upward movement of the bike.

As the cycle leaves the ground, you release the stored energy in the spring by standing up. This propels the bike back to the ground where it belongs.

Upon landing, both wheels should make contact at nearly the same time. Never land in a front-wheel-high attitude, as that wastes time and unduly loads up the rear wheel and bottoms the shocks. Often, the rear tire will dig in a bit as it lands and slap the front wheel to the ground, bottoming the forks. This is extremely hard on the bike, not to mention the rider. You won’t always land on both wheels at the same time.

At times the rear wheel will touch down an instant before the front, or the front will land an instant before the rear.

The idea is to bend the trajectory of the bike into a low, flat arc to get back to the traction in the least amount of time. Once in a while you will land directly on the front wheel. Don’t sweat it. Contrary to popular belief, it is not a mortal sin to land front wheel first.

In racing, you often see front wheel landings from jumps. It is a sign that the rider is bending the bike into a flat arc rather than letting it loft too high.

Every motorcycle has slightly different jumping characteristics. Some jump front wheel high, some front wheel low, and occasionally a bike will be neutral, landing both wheels at the> same time. You will know best which category your personal machine fits into. To give you an idea of what I mean, Huskys, Monoshock Yamahas, Ossa Phantoms and late model Bultacos are light at the front wheel. Maicos and late model CZs are more neutral, as are Pentons and Montesas. Old model CZs and early Honda Elsinores are among the front-wheel-heavy group. Most enduro models will be in this last group too.

JUMP TECHNIQUES

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Physical size of the rider will also affect the way a bike jumps. Taller riders usually make the best jumpers because their longer legs allow more of the suspension effect in absorbing the jump. A tall rider, however, exerts more leverage on the handlebars, and consequently many tall riders have a problem jumping in a front-wheel-high mode. Shorter riders have the advantage of being able to get lower on the bike while it is in the air, and they seem to have an easier time landing flat.

Modifications to your bike can also affect jumping characteristics. Accessory footpegs and handlebars often change the balance point of the motorcycle. Frame modifications will completely alter jump habits. For instance, a movement of the engine forward or backward just half an inch changes the entire handling pattern of the machine. One full inch of movement will create a completely different motorcycle in every respect. Long-travel suspension modifications also change jumping characteristics, usually for the better. Long travel at the rear of the bike will increase the load on the front wheel over the stock setup. Long-travel suspension absorbs more of the jump, and the increased weight transfer to the front makes the machine jump flatter.

No matter how your machine is personalized, you can compensate for any jumping tendency by adjusting your stance. If the motorcycle is front-wheellight, stand forward more as the bike goes up the approach ramp. Taller riders may have to lean their upper body and head well forward by bending at the waist. Having ridden Huskys so long, I have become used to riding a front-wheel-light machine. So I had trouble adjusting to the jumping habits of my Ossa Phantom. Before getting the hang of it, I twice wheelied the new bike over backwards off jumps . . . one time in fourth gear, the other in fifth! I have since compensated by riding with my weight well forward at all times. You can make the same sort of adjustment on your bike if you are constantly landing too high with the front wheel.

If your machine already jumps flat, you have no problem. To compensate for a front-wheel-heavy bike, adjust your body weight farther back over the saddle. Constant, unintended frontwheel landings can also be caused by shutting off too soon before the apex of the jump, or by snapping the throttle off as your body sags toward the seat. You must remain standing, and the throttle must be on until reaching the apex for a smooth, efficient jump.

Earlier, I mentioned that you should land from a jump with the gas on. Here’s why. When you land with the power off as most riders do, the rear wheel is stressed much more heavily than in a power-on landing. Imagine your bike suspended 10 feet above the ground without a rider. Now cut the rope holding it up, and the machine drops. When it hits, all the downward force is concentrated on a very small portion of the wheel surface. When you land from a jump with the power off, much the same thing happens. The load is concentrated around approximately onefifth of the circumference of the wheel. This causes early wheel failure, flat tires and broken axles. The suspension bottoms out also, overloading the shocks and your body.

Some racers will turn the throttle on at the same moment they touch ground. This is no better than the first method. In the air, the teeth of the transmission gears are freewheeling, as is the clutch. When you land, then apply throttle, the gears lash together, the clutch tabs smack against their mounting slots, and the chain snaps tight. The heavy load on the tire and wheel is the same as before. All of these things contribute to extra wear on the engine and drive components, and can be avoided with the proper jump technique.

WTiile still airborne, roll the throttle back on before the tires touch ground again. Not just an instant before, but well before you make contact. This technique is beneficial for many reasons. First, the load on the spinning rear wheel is comfortably distributed around three-quarters of the circumference or more. Wheels are designed to take loads in this manner. The tube never becomes pinched between the rim and tire as the tire smashes flat because the tire no longer squashes down so much. The chain slack is taken up while the machine is still in the air so that there is no sudden lash or snap as you contact the ground again. The lash, or clearance, between the gears and between the clutch parts is also taken up before any sudden load is applied. As you touch down, the madly spinning rear wheel shoots the bike ahead, lessening the load on the suspension. This action often keeps the shocks from bottoming out at all when landing. The result is a less destructive force on the shocks and on the rider. This new jumping technique will help you land wi the grace of a hummingbird rather th¡ a thrown sack of potatoes.

Remain standing on the pegs as the bike returns to the ground. Use your legs to cushion the landing. If you collapse down on the seat, the shocks will surely bottom out. A stand-up landing will also prepare you for any unexpected terrain changes following a jump.

UPHILLL JUMPS

All procedures for uphill jumps are the same as for flatland jumps, except body position. Getting the front wheel too high is the main problem on uphill jumps. If you get the front wheel up you will be forced to shut off and lose momentum. To avoid this, adjust your weight well forward. It is usually best

keep the throttle on while the bike ir. The time you are in the short so there is little chance harming the engine. Holding the throttle on in the air builds up rpm against any speed loss on the slope. Many times it is best to land front wheel first on uphill jumps.

DOWNHILL JUMPS

Downhill jumps require a rearward stance on the machine. Always stand up. Don’t hit a downhill jump with your butt in the saddle or the bike will loft too high. Try to jump down the hill, not out away from it. You want the wheels to be parallel to the downhill surface. If the front wheel sags too low, a heavy burst of throttle will bring it back up. It isn’t always possible to land with the gas on from a downhill jump. It depends entirely on the runout area.

PEAKED JUMPS

Peaked jumps are found at the top of hills where the bike wants to jump

straight up. As you near the apex of this sort of jump, drag the rear brake up the slope. The effect is the same as when you wheelie and hit the rear brake: The front wheel drops immediately. By dragging the rear brake you make the front wheel heavy. Keep your weight forward. Stand up, of course, before the jump; and as the front wheel clears the top, ease off the rear brake and thrust your arms out straight, pushing the machine away from you. This makes the motorcycle jump in a flat arc rather than straight up. Turn the throttle on while you are still in the air, stand up, pushing the bike back to the ground, and prepare to cushion the landing with your legs.

FALL-AWAY JUMPS AND DROP-OFFS

Stand up in advance and keep a steady throttle. You want to avoid giving a last second burst of throttle and a pull on the bars to keep the bike from lofting. As you reach the apex or ledge, flex your knees and crouch slightly to get the spring effect mentioned earlier. Let the bike drop straight down to the lower level. Push with your legs to help it. Don’t pull up on the bars at all! Your speed will keep the bike perfectly flat if you have positioned your body weight correctly. Land with the gas on. If the drop is a short one, don’t shut off at all, especially if you are landing in sand and you can see that the way ahead is clear. Many riders crash hard when dropping into sand. This is because they land with the throttle off. The sand stalls the rear wheel for an instant and the inexperienced rider is pitched forward onto, and sometimes over, the handlebars. >

6.

7.

8.

9.

SERIES JUMPS

Successive jumps can be very tricky. You need to establish a rhythm to correctly negotiate a series of jumps in the desert without getting out of shape. If the jumps are extremely close together, and taken in, say, second gear, try to jump onto the back of the next jump each time the machine leaves the ground. You must keep the front wheel high to do so. The wrong rhythm will make you straddle the jumps occasionally, but that can be a good technique too if the jumps are not too high. Don’t rush the bike. Let it do the work. Stand tall and allow the motorcycle to "work” under you. A steady throttle works better than blipping the power on each jump. Look to the edges of the course where the jumps may be lower than in the middle.

JUMPS FOLLOWED BY TURNS

If you can see ahead of time that there is a corner immediately following the next jump, plan to land on the front wheel. The front wheel is the one that steers the bike. If you jump in the normal manner you may miss the turn altogether because you won’t have enough space to land, then steer. By landing front wheel first, you will be prepared for the turn. This technique is very useful for passing in this sort of section.

FRONT WHEEL LANDINGS

Most people avoid front-wheel landings because they are afraid of endos. Racers seldom avoid wheelies because of the possibility of going over backwards, though. It must be more psychologically damaging to consider falling forward than to consider falling backward. In any case, both types of falls can usually be avoided. The front wheel landing is a useful tool in your racer’s bag of tricks. I practice front-wheel landings for the same reason I practice skidding the front tire with the front brake. I will skid the front tire in competition in the heat of battle. Likewise I am sometimes going to land on the front wheel. When either thing happens I want to be prepared and able to maintain control. When you land on the front wheel, immediately shift your weight to the rear. Land with your arms extended so that you can hold yourself back. This prevents weight transfer to the front in this dangerous situation. If the front wheel sags really low while you are still in the air, snap the throttle wide open and hold it open. Don’t worry ¿bout the engine exploding. It won’t. It is a natural law that a spinning body gains mass (weight) as it spins faster. What you are doing by screeching the motor is spinning the rear wheel super fast. This causes the wheel to become heavier, in effect, and pulls the bike more level. This will often save you from an endo. Top riders have this protective device wired to their brains. When the front wheel gets dangerously low, it is an automatic reflex to snap the throttle to the stop.

Practicing front-wheel landings is easy. Take a small bump and use low to moderate speed. As you go over the bump, lean forward and let the rear wheel kick up slightly. When you become comfortable with the feeling, you can try the technique on an actual jump. When you do practice on a jump, try to land flat at first. Gradually you can progress to adjusting your weight so that the bike lands slightly on the front wheel. Don’t get too steep with your landing angle. It isn’t necessary. You only want to accustom yourself to the feeling of front wheel landings. This is just one more practice technique to help you increase your control of the motorcycle.

WATER CROSSINGS

Water crossings should be jumped whenever possible. In the middle of a dusty race, you don’t want to get the bike wet. Look for some small bump before a water crossing that may assist you in your jump. If you can’t jump the water, try to wheelie across. Shift down a gear to get the best pulling power. Just before you reach the water, shift your weight back, pull on the bars and roll the gas on. Shallow streams take less throttle. You don’t want to wheelie over backwards into the water. On deeper streams, loft the front wheel higher, as the drag of the water is liable to bring the wheel down right in the middle of the crossing. If that happens you will really get wet! If you know a water crossing is shallow, and it is located in a fast section, try to hit the crossing with the front wheel high at top speed. This keeps you dry and your goggles free of splashes. If you’re racing another rider through a crossing, duck your head down if you don’t beat him to the water. His splash will then hit the top of your helmet rather than catch you in the face. It might even be refreshing. When you encounter an unknown water crossing that looks deep, stand on the pegs and trials through. This keeps splash to a minimum and prevents the machine from watering out.

When you jumped back into the rough after the dry lake you felt like a jackrabbit for a while. The bike seemed to be either in the air or constantly landing from a jump. It was a fight at first, until you got into a good rhythm, then the lumpy terrain began to become more enjoyable. Getting rid of the bad habit of landing with the front wheel high all the time was your first major accomplishment in jumping technique. Nice, flat arcs and right back to the ground is your method now. 0

10.

11.

12.

13.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue