Pro Off-Road Racing: What's It Like To Race In Baja?

Editor’s Note. Much has been written about professional off-road races, but we feel there’s much more to the stories of these events when you look behind the scenes. We did just that in conjunction with this year’s Baja 500. We followed the planning and activities of two Southern California sportsman riders who entered the 500 for the first time. Ron Griewe (36) and Jim Ericson (34) are both AMA District 37 desert experts of long standing. They had been growing tired of the local races so when SCORE lowered the motorcycle entry fee from $350 to $225 for the 500, they decided to give it a try. Although this story deals primarily with the experiences of Jim and Ron, we feel that this account is close to what the average newcomer to Baja racing can expect.

What's It Like To Race In Baja?

NO MATTER HOW you look at it, Baja racing is a whole new experience. And it’s mind boggling for anyone who is not familiar with the country and has never been riding there before. Distances between civilized outposts are great. Pit support is difficult to organize and is expensive because of the number of people and vehicles required. There is a very real possibility of having to race at night in the short 500-mile version. In the 1000, night racing is a cold, hard reality.

From this brief description, it’s not hard to come to the conclusion that Baja racing and/or pro racing in general is extremely difficult. That’s why there is so much prestige involved in entering or winning. And that’s why people do it.

Is There Any Money ln It?

Yes. There’s tons of money in Baja racing .. . tons of money for everyone but the racers. Any biker thinking this is the place to make some big bucks is in for a big surprise. Even the I st-place winners in each of the three displacement categories win only a few thousand dollars in prize money. And when you compare a few thousand dollars to what it takes to win, you can see that it’s not even a break-even proposition. Consider Ron’s and Jim’s expenses for the 500.

Bike Preparation Costs

RM370 Suzuki $1500.00 Vesco desert tank $44.00 Preston Petty lB front fender $8.00 Preston Petty IT rear fender $16.00 K&N HA-14 handlebars $18.00 K&N air filter (2) $20.00 FMF (Pro-Fab) swinging arm $125.00 Works Performance shocks $11 5.00 Fork modifications $35.00 D.I.D. rims $60.00 D.I.D. #520 drive chain (2) $70.00 FMF expansion chamber $83.00 Fun `N Fast skid plate $25.00 Circle Industries sprockets (2 sets) $31.00 Yokohama 4.60-18, 905 rear tires (2) $70.00 Yokohama 3.25-21 front tires (2) $40.00 Static arm modification $ 15.00

A.C.P. sealer/balancer $6.00 Spare levers (clutch and brake), control cables, misc. parts and tools carried on bike and riders $50.00

Race, Pre-Run And Pit Support Costs

Entry fee $285.00 Gasoline $225.00 Food $210.00 Seven plastic gas cans $63.00 Pit markers $25.00 Seven cans of chain spray $ 1 1.00 Three tire pumps $25.00 Compressed air tank (home-made) $25.00 Ten spare tubes $40.00 Two Hondaline enduro jackets $120.00 Two pair JT racing gloves $50.00 Bike and helmet identification $25.00 Victory dinner for pit support personnel Canceled TOTAL $3475.00 Note: Much more in the form of tools and supplies was used, but these items can usually be borrowed from friends and pit helpers. In the final analysis then, Baja racing can cost you a lot of money, or it can cost you more.

What’s The 500 Course Like?

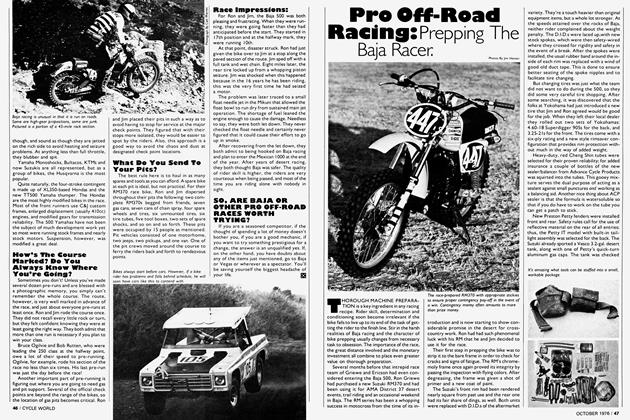

The answer to this question could fill a book. Briefly, though, the Baja 500 is 435 miles long and it is not an off-road race. The truth of the matter is, you never leave the road. This knowledge may set your mind at ease, but it shouldn’t because the term road in Baja is used quite loosely. In fact, some of the roads used in this year’s course could be considered more than challenging. Words like grim or total junk best describe their condition.

But it’s not all bad. The racers only consider about 25 percent of the course to be really “rough”. There are some fast stretches though . . . stretches where wide open is not even enough. Halfway around the course, there’s a 36-mile-long stretch of pavement that is as straight as a string. There’s also a lake bed some I 5 miles long that can be run in high gear all the way.

Much of the course is comprised of unique double-rut sand roads which twist and turn all over the peninsula. Over the years some of these roads have built up berms in the corners, many exceeding three feet in height.

There are a couple of particularly bad rocky downhills to be met along the run. These caused the demise of quite a few of the Baja Bugs and trucks used by racers for pre-runs.

The course runs from sea level all the way to 5000 feet. Temperatures vary from the high 30s to the low 100s. Because of these extremes, careful thought must be given to jetting the engines and clothing the riders.

Still, to the racer, the most significant part of the Baja experience is the distance covered. The race is roughly five times the length of the average enduro. Fortunately, this year’s event lends itself to frequent rider changes, as the route stays near paved roads most of the time. Ron and Jim changed over three times during the race.

To win, you have to be fast and strong. The winning team of Larry Roeseler and A.C. Bakken only made one rider change and that occurred at the halfway point. As far as speed goes, they averaged 47.84 mph. In a single I hour and 14 minute section, they averaged an incredible 61.62 mph.

How Long Does The 500 Take?

It took Larry and A.C. 8 hours and 50 minutes to complete the course. Some riders raced through the night. A few didn’t finish until dawn the next day, a full 24 hours after the first bikes began the ordeal.

Which Type Of Bike Is Best For The Race?

If you only consider this year’s results, you’d have to go with the two-strokes. The best-placing four-stroke ended up 4th overall behind the ring-dings. Also, the law of averages is on the side of the two-strokes since they’re about 75 percent of the entries.

The most dominant two-stroke effort is that of Husqvarna. There are a lot of Huskys in the race and the factory supports many of the best riders for this type of event. It is understood that many of the open class Huskys are actually 360cc CR models done up like WRs. Three of the WR’s gears and its large gas tank are mated to the more potent CR model. The bikes appear quite stock,

though, and sound as though they are jetted on the rich side to avoid heating and seizure problems. At anything less than full throttle, they blubber and sDit.

Yamaha Monoshocks, Bultacos, KTMs and now Suzukis are all represented, but as a group of bikes, the Husqvarna is the most popular.

Quite naturally, the four-stroke contingent is made up of XL350-based Hondas and the new TTSOO Yamaha thumper. The Hondas are the most highly modified bikes in the race. Most of the front runners use C&J custom frames, enlarged displacement (usually 4 10cc) engines, and modified gears for transmission reliability. The 500 Yamahas have not been the subject of much development work yet so most were running stock frames and nearly stock motors. Suspension, however, was modified a great deal.

How's The Course Marked? Do You Always Know Where You're Going?

sometimes you con t: unless youve mace several dozen pre-runs and are blessed with a photographic memory, you simply can't remember the whole course. The route, however, is very well marked in advance of the race, and just about everyone pre-runs at least once. Ron and Jim rode the course once. They did not recall every little rock or turn, but they felt confident knowing they were at least going the right way. They both admit that more than one run is necessary if you plan to win your class.

Bruce Ogilvie and Bob Rutten, who were leading the 250 class at the halfway point, owe a lot of their speed to pre-running. Ogilvie, for example, rode his section of the race no less than six times. His last pre-run was just the day before the race!

Another important part of pre-running is figuring out where you are going to need gas and pit support. Several of the official check points are beyond the range of the bikes, so the location of gas pits becomes critical. Ron and Jim placed their pits in such a way as to avoid having to stop for service at the major check points. They figured that with their stops more isolated, they would be easier to spot by the riders. Also, this approach is a good way to avoid the chaos and dust at designated check point locations.

What Do You Send To Your Pits?

The best rule here is to haul in as many spares and tools as you can afford. A spare bike at each pit is ideal, but not practical. For their RM370 race bike, Ron and Jim dispersed throughout their pits the following: two com plete RM37Os begged from friends, seven gas cans, seven cans of chain spray, four spare wheels and tires, six unmounted tires, six tire tubes, five tool boxes, two sets of spare shocks, and so on and so forth. These pits were occupied by I 5 people as mentioned. Pit vehicles consisted of one motorhome, two jeeps, two pickups, and one van. One of the pit crews moved around the course to ferry the riders back and forth to rendezvous points.

Race Impressions:

For Ron and Jim, the Baja 500 was both pleasing and frustrating. When they were run ning, they were going faster than they had anticipated before the start. They started in I 7th position and at the halfway mark, they were running 10th.

At that point, disaster struck. Ron had just given the bike over to Jim at a stop along the paved section of the route. Jim sped off with a full tank and wet chain. Eight miles later, the rear tire locked up from a whopping piston seizure. Jim was shocked when this happened because in the I 6 years he has been riding, this was the very first time he had seized a motor.

The problem was later traced to a small float needle jet in the Mikuni that allowed the float bowl to run dry from sustained main jet operation. The shortage of fuel leaned the engine enough to cause the damage. Needless to say, they were both let down. They never checked the float needle and certainly never figured that it could cause their effort to go uD in smoke.

After recovering from the let down, they both admit to being hooked on Baja racing and plan to enter the Mexican I 000 at the end of the year. After years of desert racing, they both thought Baja was safer. The quality of rider skill is higher, the riders are very courteous when being passed, and most of the time you are riding alone with nobody in sight.

SO, ARE BAJA OR OTHER PRO OFF-ROAD RACES WORTH TRYING?

If you are a seasoned competitor, if the thought of spending a lot of money doesn't bother you, if you are a good mechanic, if you want to try something prestigious for a change, the answer is an unqualified yes. If, on the other hand, you have doubts about any of the items just mentioned, go to Baja or Vegas or wherever as a spectator. You'll be saving yourself the biggest headache of your life.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue