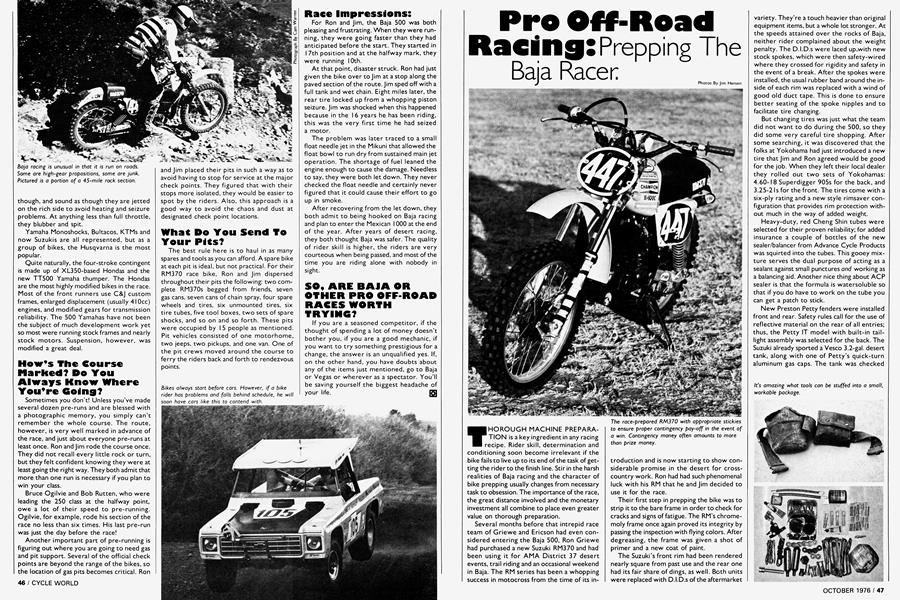

Pro Off-Road Racing: Prepping The Baja Racer.

THOROUGH MACHINE PREPARATION is a key ingredient in any racing recipe. Rider skill, determination and conditioning soon become irrelevant if the bike fails to live up to its end of the task of getting the rider to the finish line. Stir in the harsh realities of Baja racing and the character of bike prepping usually changes from necessary task to obsession. The importance of the race, the great distance involved and the monetary investment all combine to place even greater value on thorough preparation.

Several months before that intrepid race team of Griewe and Ericson had even con sidered entering the Baja 500, Ron Griewe had purchased a new Suzuki RM370 and had been using it for AMA District 37 desert events, trail riding and an occasional weekend in Baja. The RM series has been a whopping success in motocross from the time of its introduction and is now starting to show con siderable promise in the desert for cross country work. Ron had had such phenomenal luck with his RM that he and Jim decided to use it for the race.

Their first step in prepping the bike was to strip it to the bare frame in order to check for cracks and signs of fatigue. The RM's chrome moly frame once again proved its integrity by passing the inspection with flying colors. After degreasing, the frame was given a shot of primer and a new coat of paint.

The Suzuki's front rim had been rendered nearly square from past use and the rear one had its fair share of dings, as well. Both units were replaced with D.l.D.s of the aftermarket variety. They're a touch heavier than original equipment items, but a whole lot stronger. At the speeds attained over the rocks of Baja, neither rider complained about the weight penalty. The D.l.D.s were laced up~with new stock spokes, which were then safety-wired where they crossed for rigidity and safety in the event of a break. After the spokes were installed, the usual rubber band around the in side of each rim was replaced with a wind of good old duct tape. This is done to ensure better seating of the spoke nipples and to facilitate tire changing.

But changing tires was just what the team did not want to do during the 500, so they did some very careful tire shopping. After some searching, it was discovered that the folks at Yokohama had just introduced a new tire that Jim and Ron agreed would be good for the job. When they left their local dealer they rolled out two sets of Yokohamas: 4.60I 8 Superdigger 905s for the back, and 3.2 5-2 Is for the front. The tires come with a six-ply rating and a new style rimsaver con figuration that provides rim protection with out much in the way of added weight.

Heavy-duty, red Cheng Shin tubes were selected for their proven reliability; for added insurance a couple of bottles of the new sealer/balancer from Advance Cycle Products was squirted into the tubes. This gooey mix ture serves the dual purpose of acting as a sealant against small punctures and working as a balancing aid. Another nice thing about ACP sealer is that the formula is watersoluble so that if you do have to work on the tube you can get a patch to stick.

New Preston Petty fenders were installed front and rear. Safety rules call for the use of reflective material on the rear of all entries; thus, the Petty IT model with built-in tail light assembly was selected for the back. The Suzuki already sported a Vesco 3.2-gal. desert tank, along with one of Petty's quick-turn aluminum gas caps. The tank was checked over and a fresh Vesco petcock fitted.

K&N model HA-14 chrome-moly bars were selected for the bike. They have nearly the same bend as the stock RM bars, but are a whole lot stronger. The bars were outfitted with K&N’s foolproof, blade-type kill button and a pair of dogleg Magura levers on stock swivels. All three control cables were replaced with new Terry Davis units. Just to be sure that cables would not be a problem during the race, spares were gray-taped along the length of the originals. CR Honda cable guides were chosen over the stock units. The stock throttle assembly was retained, but Allen heads were brazed to the mounting screws at the throttle and on the plate holding the needle in the carburetor slide. Allen bolts were also used to replace stock hex bolts and screws on the engine side cases, handlebar mount and seat mount. In addition to the extra security they provided, these changes also helped standardize the types and sizes of tools to be carried on the machine.

Protection for the underbelly of the engine was provided by a steel skidplate manufactured by Fun ’n Fast. The plate was installed using all of the stock hardware only after Ron and Jim decided that they could not improve on the original design. The Fun ’n Fast plate is designed specifically for RMs and contours to the vital engine areas very well.

Many miles of desert racing and Baja trail riding were invested in suspension experimentation. The standard RM370 suspension setup draws mixed reviews from different riders. It seems that nobody classifies the Suzuki suspension as average for a contemporary bike. They either love it or hate it. Since the RMs were designed specifically for motocross work, the harsh ride and damping tends to be favored more by MX competitors than by cross-country or desert racers.

Lots of things were tried on Ron’s bike before the desired results were achieved. For the wide-open running necessary for Baja, the fork action needed to be softened up, but not at the expense of total damping. The following combination of ingredients seemed to be the ticket: The stock springs were retained and 8.5 oz. of Bel-Ray LT-100 5-wt. shock oil was used in each leg. The small damper valves that are held in place by the circlips in the bottom of each leg were given additional grooves—'/4 x Vi6 in. —across their faces. The long Suzuki top-out springs were replaced by shorter (Vs-in.) springs from a late model Husqvarna G.P. Static seal drag was cut in half by the use of new Teflon-coated seals like those used in the ’76 model air fork Yamahas with 36mm stanchion tubes. For added seal protection, rings of filter foam were fitted under the fork wipers to keep dirt away from the seal area. These modifications provide a super smooth ride over all surfaces, yet full front-end control is maintained. Travel is increased to 9 in. and more than 4 in. of slider engagement is left for a margin of safety.

The Suzuki’s rear suspension was changed radically. Some previous swinging arm cracking problems sent the team in search of a better product. After making some inquiries, a new box-section aluminum arm fabricated by Pro Fab and marketed by the Flying Machine Factory was selected. This massive arm was mated to the frame by use of the stock Suzuki needle bearings, spacer and bolt. All the stock components bolt right up into place. However, the team chose to go with a hardened steel replacement axle, again made by Pro Fab. The stock RM piece tends to bend quite easily, making quick removal for tire changes difficult. The static arm mount on the new swinging arm was not used; rather, an additional mount was welded to the back of the frame cradle. To this mount was bolted a homemade static arm, providing for fullfloating braking . . . much superior on long downhills.

Shock selection was easy. Griewe’s tried and true Works Performance dampers were bolted right onto the new aluminum arm. Stock bottom mounting position was retained to provide an average mechanical advantage of 1.8:1. Although they were far from brandnew, the Works Performance shocks offered all the desired features needed for such a long race. Large, .50-in.-diameter shafts with enough stroke to give more than 8.5 in. of wheel travel, lots of oil capacity for cooler running, soft ride and unique ball check valving for severe “spike loads,’’ all go into the design of these shocks.

Very tall is the best description of the bike’s gearing. Circle Industries sprockets were purchased for front and rear. To take full advantage of several fast sections of the Baja 500 course, a I 5-tooth front cog was used in conjunction with a 46-toother in back. The power transmission from front to rear was handled by a top-of-the-line D.I.D. chain. D.I.D., like some other manufacturers, offers more than one grade of chain. This chain is so tough that break-in runs failed to stretch it at all.

Many a Suzuki RM owner has experienced problems with his/her bike's rear sprocket setup. If the sprocket bolts are kept tight and hit with Loc-Tite from the start, there's no problem. But if the mounting bolts are al lowed to loosen even once, you can never count on their staying tight again. After much frustration this problem was finally solved. The sprocket bolt holes in the hub were tapped and threaded with a standard Amer ican ¾-in, tap. Then 18 threaded /8 x I ½-in heavy-duty flathead socket cap screws were threaded through the sprocket and hub and fitted with self-locking nuts. The whole assembly was treated with Loc-Tite, curing the loose sprocket problem forever. The engine of Ron's Suzuki was left basi cally stock. The most noticeable change was the installation of an FMF expansion chamber. This is an all new pipe design from the folks at Flying Machine Factory that smooths out the 370's power curve by boosting both lowand high-end response without affecting mid range power. The pipe runs up over the engine and snakes through the frame just like the stock part. The Suzuki mounting brackets are retained, making for a very neat installation. The pipe is topped off with a token muffler. While not very quiet, it is slightly less offensive than the factory si lencer. Just to make sure the bike finished with the muffler still intact, the mounting tabs were beefed up and double retaining springs fitted.

On the other end of the motor, a K&N air filter was mounted in the RM's airbox. The tremendous reputation of the K&N filter lies in its ability to go without servicing for long periods. It would allow the Baja bike to go the full 500 without a change. Pre-running proved the K&N capable of withstanding all the dirty miles the course could offer.

Spark was supplied by a Champion N2G plug covered by a Malcolm Smith cap. The engine was completely torn down and all parts inspected and measured before reassembly. Pennzoil 20W/40 filled the transmission, while Pennzoil two-stroke oil went into the 32: I pre-mix. To ensure that the pre-mix stayed clean, an automotive-type AC fuel filter was fitted to the gas line.

In case you've been wondering why the price of Loc-Tite stock has doubled on the big board, it's because of the heavy sales the stuff enjoyed during the construction of this motorcycle. Tube after tube was liberally used throughout all stages of assembly. With final construction complete, it was time to engineer the spares and tools to be carried on the bike and riders.

The game plan was to pack as many tools and parts as possible without their becoming a handicap or hindrance to the riders. Rules for this race wisely require participants to carry a quart of water, survival food, matches and an approved first aid kit. While scrounging through the local surplus store, Ron came across a small (I .5 x 5-in.) Army first aid kit. The bag was fastened to the Army canteen belt. One whole evening was spent packing this bag with bits and pieces. It is truly amazing what can be stuffed into such a small con tamer when you work at it. Here's the list The tools to be carried during the race were all secured to various parts of the bike. In addition to the ever faithful plug wrench, there were four double-end wrenches banded to a right rear downtube. Another I 0/I 2mm wrench for brake adjustments was mounted below the right numberplate, while the two required Allen wrenches were taped to the handlebar. Hidden behind the right numberplate was a special screwdriver handle and three heads for same. A small vice grip with cutter was clamped to a frame tube near the carb, and a set of tire irons was banded to the fork tubes between the triple clamps.

All of this was carried on the rider's can teen belt and yet was so compact that it never made its presence known.

(Continued on page 88)

Continued from page 49

Carried on any still vacant portions of the Suzuki were the following:

Amazingly enough, all of this gear was attached to a dirt bike without falling off or getting in the way of the riders during the course of the race. The only item used by either rider was the small wrench to adjust the rear brake about I 80 miles into the race.

But even all of this heavy preparation was no match for the engine seizure suffered midway through the race on the 36-mile paved section. There’s only so much you can do out in the middle of nowhere with minimal tools. The seizure was ultimately traced to an extremely lean condition caused by a lack of gas in the float bowl. The Suzuki’s 36mm Mikuni was supplied with a float needle jet 3.0mm in size. This jet works just fine for motocross and even trail riding, but the sustained main jet running down the pavement caused the float bowl to run dry. The sea-level altitude of the road and 100° temperatures were also factors in the engine’s demise. A float needle jet of 3.6mm has since replaced the original, and subsequent tests indicate that the problem is solved. So, with the aid of hindsight, Jim Ericson and Ron Griewe have begun plans for the Mexican I 000 this fall.

Now you have some idea of what can be done to prepare a bike for that really long haul. Going to such lengths may seem extreme, but unlike the “On Any Sunday” motocross and enduro events, the big Baja races come just twice a year. Ron and Jim have six long months to contemplate that $2 jet that dealt their fatal blow. RSI

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound·up

OCTOBER 1976 -

Letters

LettersLetters

OCTOBER 1976 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

OCTOBER 1976 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Dept

OCTOBER 1976 By Allan Girdler -

Features

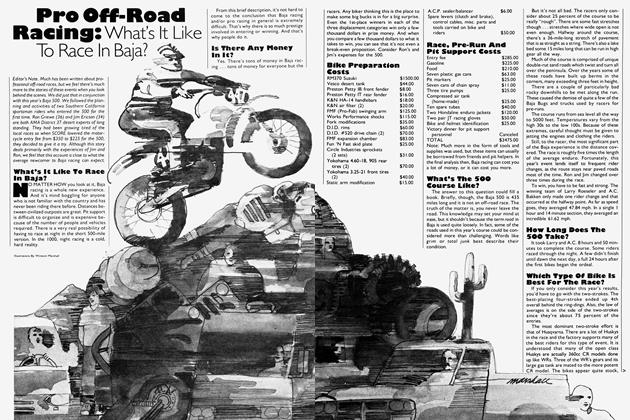

FeaturesPro Off-Road Racing: What's It Like To Race In Baja?

OCTOBER 1976 -

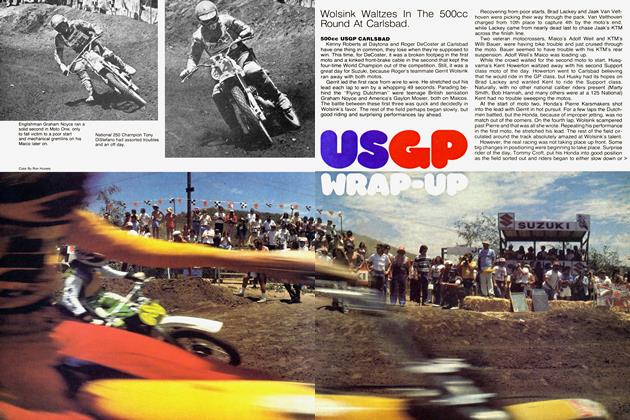

Usgp Wrap-Up

Usgp Wrap-UpWolsink Waltzes In the 500cc Round At Carlsbad.

OCTOBER 1976