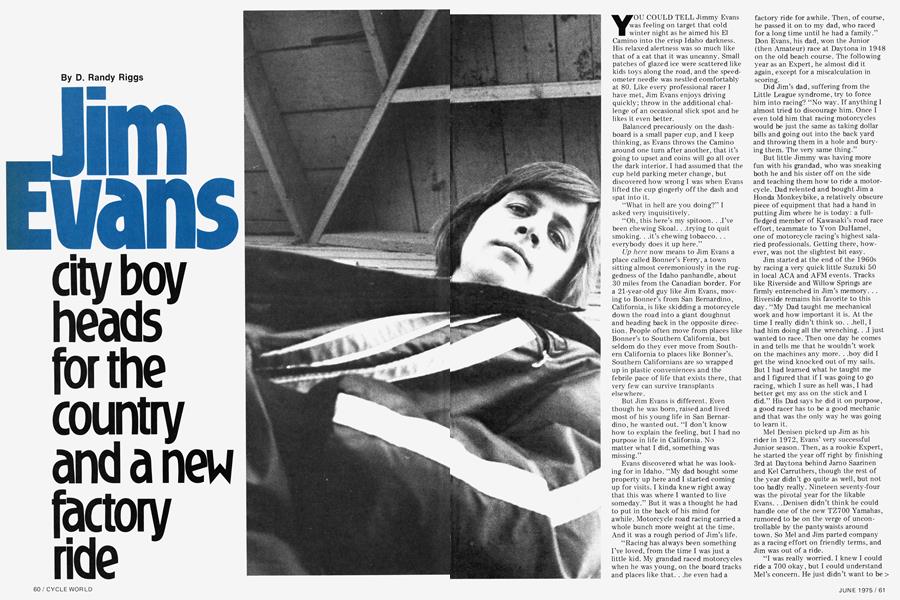

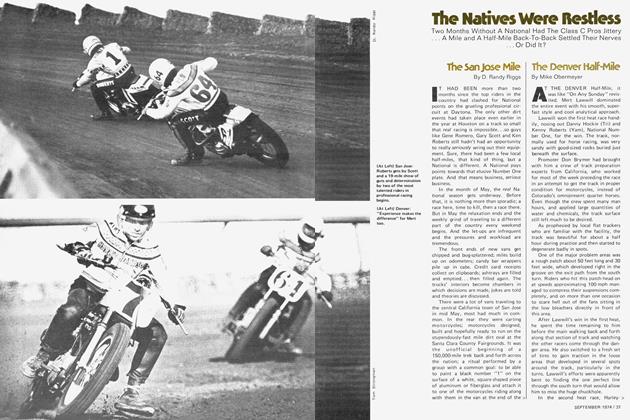

Jim Evans

city boy heads for the country and a new factory ride

D. Randy Riggs

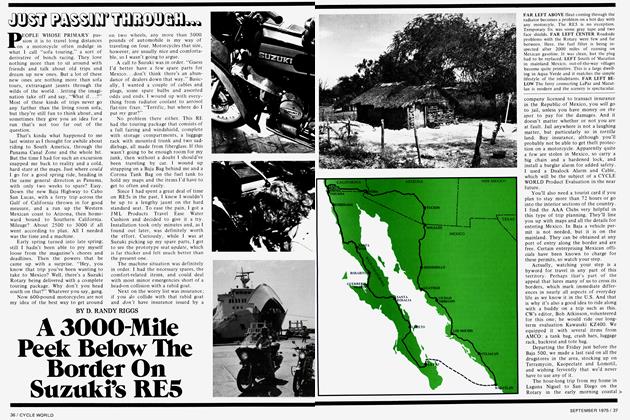

YOU COULD TELL Jimmy Evans was feeling on target that cold winter night as he aimed his El Camino into the crisp Idaho darkness. His relaxed alertness was so much like that of a cat that it was uncanny. Small patches of glazed ice were scattered like kids toys along the road, and the speedometer needle was nestled comfortably at 80. Like every professional racer I have met, Jim Evans enjoys driving quickly; throw in the additional challenge of an occasional slick spot and he likes it even better.

Balanced precariously on the dashboard is a small paper cup, and I keep thinking, as Evans throws the Camino around one turn after another, that it’s going to upset and coins will go all over the dark interior. I had assumed that the cup held parking meter change, but discovered how wrong I was when Evans lifted the cup gingerly off the dash and spat into it.

“What in hell are you doing?” I asked very inquisitively.

“Oh, this here’s my spitoon. . .I’ve been chewing Skoal. . .trying to quit smoking. . .it’s chewing tobacco. . . everybody does it up here.”

Up here now means to Jim Evans a place called Bonner’s Ferry, a town sitting almost ceremoniously in the ruggedness of the Idaho panhandle, about 30 miles from the Canadian border. For a 21-year-old guy like Jim Evans, moving to Bonner’s from San Bernardino, California, is like skidding a motorcycle down the road into a giant doughnut and heading back in the opposite direction. People often move from places like Bonner’s to Southern California, but seldom do they ever move from Southern California to places like Bonner’s. Southern Californians are so wrapped up in plastic conveniences and the febrile pace of life that exists there, that very few can survive transplants elsewhere.

But Jim Evans is different. Even though he was born, raised and lived most of his young life in San Bernardino, he wanted out. “I don’t know how to explain the feeling, but I had no purpose in life in California. No matter what I did, something was missing.”

Evans discovered what he was looking for in Idaho. “My dad bought some property up here and I started coming up for visits. I kinda knew right away that this was where I wanted to live someday.” But it was a thought he had to put in the back of his mind for awhile. Motorcycle road racing carried a whole bunch more weight at the time. And it was a rough period of Jim’s life.

“Racing has always been something I’ve loved, from the time I was just a little kid. My grandad raced motorcycles when he was young, on the board tracks and places like that. . .he even had a factory ride for awhile. Then, of course, he passed it on to my dad, who raced for a long time until he had a family.” Don Evans, his dad, won the Junior (then Amateur) race at Daytona in 1948 on the old beach course. The following year as an Expert, he almost did it again, except for a miscalculation in scoring.

Did Jim’s dad, suffering from the Little League syndrome, try to force him into racing? “No way. If anything I almost tried to discourage him. Once I even told him that racing motorcycles would be just the same as taking dollar bills and going out into the back yard and throwing them in a hole and burying them. The very same thing.”

But little Jimmy was having more fun with his grandad, who was sneaking both he and his sister off on the side and teaching them how to ride a motorcycle. Dad relented and bought Jim a Honda Monkey bike, a relatively obscure piece of equipment that had a hand in putting Jim where he is today: a fullfledged member of Kawasaki’s road race effort, teammate to Yvon DuHamel, one of motorcycle racing’s highest salaried professionals. Getting there, however, was not the slightest bit easy.

Jim started at the end of the 1960s by racing a very quick little Suzuki 50 in local ACA and AFM events. Tracks like Riverside and Willow Springs are firmly entrenched in Jim’s memory. . . Riverside remains his favorite to this day. “My Dad taught me mechanical work and how important it is. At the time I really didn’t think so. . .hell, I had him doing all the wrenching. . .1 just wanted to race. Then one day he comes in and tells me that he wouldn’t work on the machines any more. . .boy did I get the wind knocked out of my sails.

But I had learned what he taught me and I figured that if I was going to go racing, which I sure as hell was, I had better get my ass on the stick and I did.” His Dad says he did it on purpose, a good racer has to be a good mechanic and that was the only way he was going to learn it.

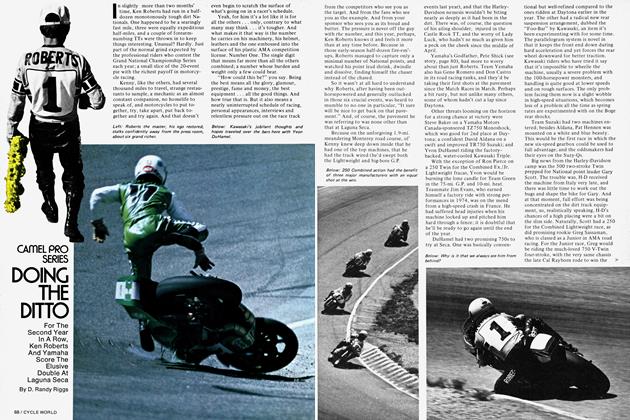

Mel Denisen picked up Jim as his rider in 1972, Evans’ very successful Junior season. Then, as a rookie Expert, he started the year off right by finishing 3rd at Daytona behind Jarno Saarinen and Kel Carruthers, though the rest of the year didn’t go quite as well, but not too badly really. Nineteen seventy-four was the pivotal year for the likable Evans. . .Denisen didn’t think he could handle one of the new TZ700 Yamahas, rumored to be on the verge of uncontrollable by the pantywaists around town. So Mel and Jim parted company as a racing effort on friendly terms, and Jim was out of a ride.

“I was really worried. I knew I could ride a 700 okay, but I could understand Mel’s concern. He just didn’t want to be a part of me getting hurt, and that’s neat, ‘cause not everyone is like that.”

At the same time, though, Denisen’s move had to play a little head trip with Evans. . .hell, when your own tuner tells you that you’re maybe not quite good enough for the best equipment. . .that’s gotta have an effect on you. And Jim says that maybe it did. Especially when he found out his ride was given to Steve McLaughlin.

“Let’s face it, already it was January and everyone had their new rides sewn up or were real close. . .1 didn’t even have a nibble. And Daytona was just around the corner. By then I’m thinking, screw it, might as well be an engineer like I’ve always wanted if racing didn’t pan out. And it wasn’t panning out, and I had this friend who was sorta in the same boat with his thing, and he’s saying that he’s gonna hang it all up and go be a doctor.” But Evans and his buddy thought they could get their training real nice like in the Army, and both went and found out all the details.

“You just don’t know how close I was to joining the damn Army. . .they really had a good program set up for me. But then my friend Pete Shick, the Yamaha racing team manager, bumps into John Jacobsen of Boston Cycles at the Cincinatti Dealer Show, who is looking for a new man to ride his 700, and mentions my name. Bingo. All of a sudden it’s to hell with the Army. . .I’m a motorcycle racer again!” It was definitely the turning point in Jim’s racing career. What about his friend? “Hell, he went and joined the Army,” Evans says with whimsy.

The Boston Cycles team really had to get with it to make Daytona, and Jim’s first ride on the 700 was just a week prior to the race. “We had fuel problems and all sorts of things going wrong. . . but with no time to prepare we half sort of expected it.” More surprises were in store.

“The next thing I know I’m getting invited to the Match Races in England as the reserve rider for the United States team. I was pumped but apprehensive. I still wasn’t used to the machine, I didn’t know any of the tracks, and a few of the guys I had never raced against. On top of that I was the reserve rider. . . nothing is harder on your nerves.”

Evans would never know until the last second before the start of the race whether or not he would be in it.

“And right off. . .bam. . .John Long’s tire goes flat on the starting line of the first race and they’re all waving at me to come on. . .whew, that’s enough to make you crazy. I’d never be a reserve rider again.” The way Evans says that last line you just know he doesn’t believe it either. True racers rarely turn down chances to race.

He learned plenty in England and loves the way the organizing bodies hold their events. “They just get everything over with in one day. . .nothing is dragged out for days on end.” And about the future of road racing in the United States? Evans’ warm blue eyes take on a steel color as he gets serious, and he’s always serious about his racing.

(Continued on page 82)

Continued from page 62

“There is no doubt that something has to be done. . .by someone, to save road racing here in the States on a National professional level. In 1973 we had nine AMA National road races, in 1974 we had six and this year we’re down to four. . .what’s it going to be next year. . .two? With few races on the calendar it doesn’t make it worthwhile for factories to compete and spend a lot of money and it sure doesn’t make it worthwhile for the privateer or partially sponsored rider to spend thousands of dollars to race three times or four. . . where they’ll probably get blown off by the factories anyway.

“I heard the AMA had about eight or nine applications for road race National sanctions around the country this year; the reason they turned a bunch of them down was because they conflicted with the dates of some dirt Nationals. Whose side is the AMA on anyway?”

Evans has an interesting suggestion, but one that will probably not be popular with many of the riders. “I say we should have a separate National Championship in road racing and dirt track racing. In other words, we could have two Number Ones, with hopefully an equal amount of races on both calendars. The AMA could try to set up the dates so they wouldn’t conflict too much, that way the guy who rides everything would have a crack at both. . .though he would have to be awfully good to become Number One in each, since he’d have to choose between one or the other on a few occasions.

And Evans feels that, above all, the spectators have to be brought closer to the action. “That’s the big reason why they get so many people to the events in Europe. . .they’re right there, on top of the action. We’ve got to have that at every race here. . .not just a couple.”

When Jimmy got back to racing in the states, he was still in the learning process on the big TZ, as was just about everyone else at the time. “We destroyed a gearbox in one race and couldn’t get parts. . .1 had to sit out the Laguna Seca National, which was really a drag.” But Evans came back strong at Talladega with a 3rd-place finish, where he rode incredibly smoothly. . . .“My mechanic, Kevin Cameron, and I just all of a sudden got it together. And it stayed together for the big Ontario event, where Jim again rode smoothly and forcefully to a very healthy 3rd place.

Shortly afterward, Kawasaki signed Jim to a two-year contract as their number two rider behind DuHamel. Evans had gotten what he had worked for for so long. . .that factory spin down the pike. But coping with the thrust into the limelight and the big move to Idaho was beginning to show on Evans. “It’s an awful lot to think about all of a sudden. . .Idaho preserves my peace of mind.”

When he’s not racing, Jim works at Larry’s Sports Center, located smack in the middle of Bonner’s main drag. “It’s just perfect for me. They sell all kinds of outdoor sporting equipment and motorcycles and snowmobiles. I work on the bikes and Snocats. . .if I have to go racing they say, ‘Good luck and see ya when ya get back!’ The people up here are unreal. . .the greatest. . .1 really dig ‘em.”

We walk out of Larry’s and down the slush-covered sidewalk of Main St.; friends and people passing never fail to say hi or toss a friendly snowball. He kicks the snow and talks about how great it’ll be to be a part of Kawasaki racing. “It’s like coming back; I raced Kaws with my dad for a long time, ya know. And my mechanic, Jeff Shetler, he and I get along great. I think we’ll have a good year once we sort out some of the bugs on the new machines.”

But Jim’s overriding future ambition is driving Grand Prix racing cars, and I question the possibility of that ever happening. “Well,” he says, “just think, a year ago I was ready to join the Army. . .and now look.”

You’re right, Jim, now look. ...

View Full Issue

View Full Issue