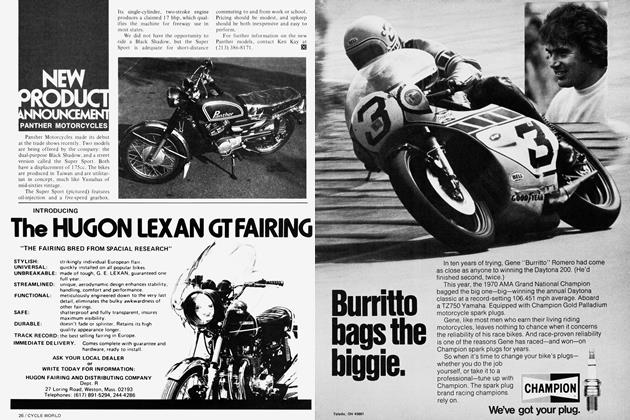

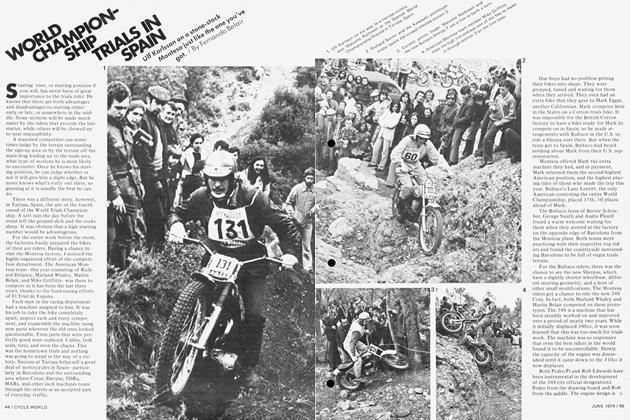

75 DAYTONA DIZZINESS

D. Randy Riggs

GO AHEAD...make your big plans for the Daytona Beach Motorcycle Speedweek...be you wealthy, educated, poverty stricken, famous, tall, short, skinny, fat, happy, sad, indifferent, doctor, plasterer, accountant, journalist, spectator, groupie or professional motorcycle racer. Make those plans and then watch them dissolve into chaos; the trailer on which you happen to be hauling your new Z1, so you can cruise the beach, seizes a wheel bearing and turns upside down behind you at 65; your mother-in-law wants to follow along on the trip so she can lay on the beach and share the motel room; plane reservations get jumbled, motel reservations get lost; there’s that ticket for an illegal left turn, for going 59 in a 55 zone, that broken fan belt, the lousy service in a restaurant, the overcrowded airport, lost luggage, snarled traffic, thumbed noses, stuck elevators and screaming kids. Lots of overtime if you’re a DB cop, a Hertz girl or an Avis guy, a street sweeper or gas station operator. All of it wildly chaotic. . .much of it normal frenzy for the Daytona twowheel crowd. Best laid plans go heiter skelter, especially for those wearing racing leathers and riding the reasons for which everyone is here to begin with.

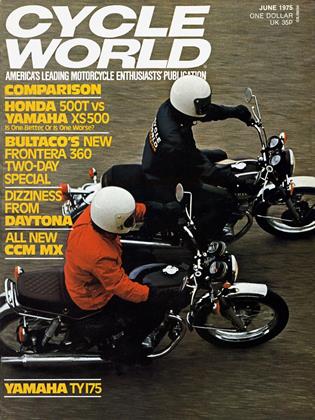

This year’s reasons; Yamaha and Ken Roberts, Yamaha and Giacomo Agostini. For some, that was reason enough. Others needed more. And there was more. Lots more.

Team Suzuki rode fresh updates of previous designs. Team Kawasaki threw legs over almost total newness. Familiar faces looked unfamiliar in new colors. And there were lots of just plain unfamiliar faces. Johnny “Who?” Cecotto was one of several, though he became the best “known” of the “unknowns” by the week’s end.

And during the week’s beginning?

Just the normal Daytona dizziness that takes those best laid plans and bludgeons them into a dusty corner.

Kawasaki went to the beach early, in hopes of sorting out its new in-line water-cooled 250 and radiator-equipped 750 Three for riders Yvon DuHamel, Jimmy Evans, Mick Grant, Barry Ditchburn and Takao Abe. But its problems were extensive, and a month wasn’t enough. Gearbox after gearbox went belly up, due to faulty circlips in the gear clusters. There was a frantic horsepower searçh; then riders DuHamel and Evans took turns hitting the pavement. Yvon wrenched his wrist and Evans cold-cocked himself for 20 minutes and cracked a collarbone. All this before the 200 even got underway!

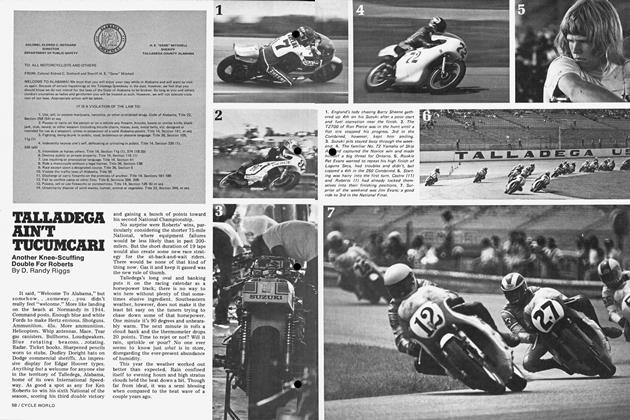

A heap of grief was in the making for Suzuki as well. Team ace Barry Sheene was conducting fuel consumption tests week prior to the race. He was a few laps into the session when his rear Dunlop tire lost the tread. . .an instant after he had shifted into sixth gear while crossing the start/finish line. This is the fastest portion of the 3.84-mile road course, and Sheene was probably just a hair under 170 mph at the time. The rear wheel locked and he was thrown down the front straight, where he bounced and tumbled nearly 300 yards! Scratch Barry and Suzuki’s best hope from the race. But he was alive and lucky to be able to say he was. Injuries included a broken left femur, collarbone, forearm, some ribs and two vertebrae.

Team manager Merv Wright flew in Sheene’s own specialist from Europe, so he was under the best of care right from the beginning. Sheene expects to race again this season, but it will probably be later in the year.

Suzuki’s woes did not end at that.

Gary Nixon, the feisty professional who nearly won the race for Suzuki last year, was attempting his first comeback since the disastrous Japan test crash last June. He had only recently gotten his remaining arm cast removed, and had been working out with Sheene in a nearby gym to get back in shape.

Though not totally up to par physically, Gary was set to ride his new lightened, six-speed, lay-down-shock Susie-Q. But it was not to be.

Sometime during the week, the screws that hold one of his bones together came out, and for all intents and purposes his arm was broken again. And in spite of the dogleg in his forearm. . . in spite of the pain, Nixon qualified the bike for the race! It was later decided that Gary shouldn’t ride, so Suzuki lost hopeful number two.

By this time the Yamahas, both 700s and 750s, factory and private entries, monoshock and conventionallysuspended models, were going quickly. Roberts, of course, was going quickest of all on the new cantilever 750. Most riders felt the new suspension was good for at least two to three seconds a lap. It’s full effect was felt on the rough banking, where the machine would remain far more stable at high speeds pulling the strong G forces. Ago was the most experienced on this type of frame, having ridden a 500 cantilever in the Grands Prix last year. But the other guys on cantilevers, Roberts, Steve Baker and Hirdyuki Kawasaki, were all smoking around pretty well.

Other Yamaha teamsters, Romero and Donny Castro, were riding new

750s, which they said had a bit more on the bottom end of the powerband.

Their machines, however, were conventional in the suspension department, much to the displeasure of Romero. His record of last season would more than justify the best equipment Yamaha could give him. He, like many, took his • share of knocks in early week practice and experimentation. But Burrito sorted out adjustments quickly and was ready when the time came.

The foreign rider contingent this year was even greater than last, many no doubt lured by the promise of great moments and past records of other foreigners. And with them came hordes of interpreters and traveling fans and foreign reporters, adding to the spectacle that is only Daytona.

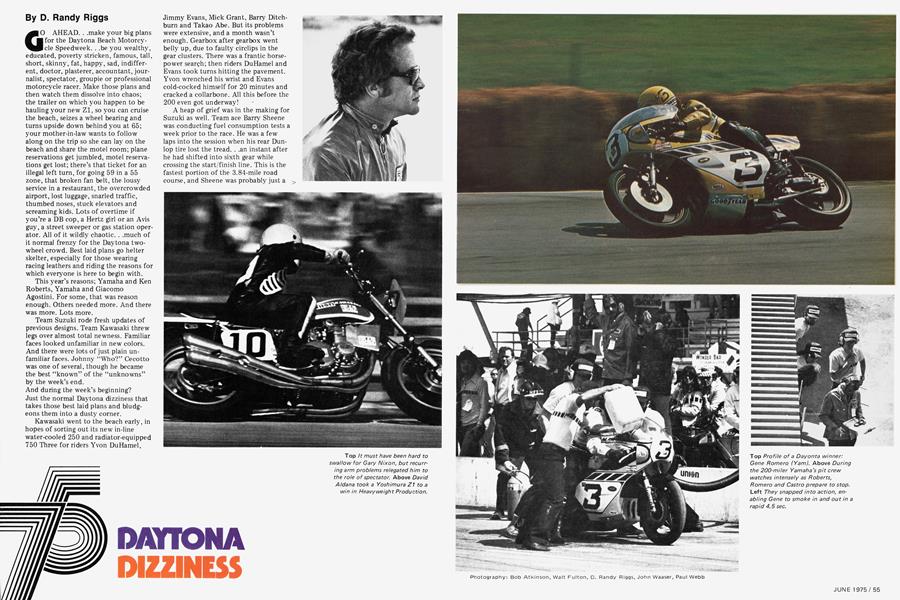

Perhaps qualifying’s only surprises were the disappointing speed turned in by Agostini. . .and the exceptional speeds turned in by “privateers” Ron Pierce, Steve McLaughlin and, most notably, the Venezuelan rider, Johnny Cecotto. The top 20 qualifiers went like so:

1. Kenny Roberts (Yam), 1 1 1.08 mph

2. Teuvo Lansivuori (Suz), 109.77 mph

3. John Cecotto (Yam), 109.09 mph

4. Gene Romero (Yam), 108.71 mph

5. Steve Baker (Yam), 1 08.3 mph

6. Ron Pierce (Yam), 107.8 mph

7. Steve McLaughlin (Yam), 107.8 mph

8. Pat Hennen (Suz), 107.4 mph

9. Giacomo Agostini (Yam), 107.3 mph

10. Takao Abe (Kaw), 106.8 mph

11. Don Castro (Yam), 1 06.7 mph

12. Warren Willing (Yam), 1 06.5 mph

13. Randy Cleek (Yam), 106.4 mph

14. Hirdyuki Kawasaki (Yam), 106.3 mph

15. Hurley Wilvert (Suz), 106.2 mph

16. Dave Aldana (Suz), 106.2 mph

17. Yvon DuHamel (Kaw), 106.1 mph

18. Wes Cooley Jr. (Yam), 1 05.8 mph

19. Patrick Pons (Yam), 105.8 mph

20. Tommy Byars (Yam), 105.1 mph

Naturally, Daytona is more than just a 200-miler, though that in itself would be enough for many. This year Production racing was added to the schedule for 350cc machines, and a Combined event with 750 and Open class entries. Couple this with Novice and Junior racing, the Combined Lightweight event, Short Track racing at night and the Alligator Enduro, and you’ve got more than enough to keep you busy!

There were more than 200 Novices this year waiting to have a go at what was for many their first professional road race. Some were very young; the winner, Dana Dandeneau, won the 76-mile race at the tender age of 17. Even though he was wearing Kawasaki leathers (that’s what his dirt tracker is), he was riding a Yamaha 250, as were 2nd and 3rd placers Cliff Guild Jr. and Dan McWhorter, not to mention the 29 riders following them!

The top-placed Juniors had a much closer go at the flag. In fact, Dale Singleton did most of the leading but ran out of fuel just before the finish. Gary Blackman then managed to just edge ahead when it counted, leaving Scott Erickson in 3rd. Ken Roberts’ protege, Skip Aksland, ran 4th. All were on Yamaha 700s.

Big news in Light racing, of course, was Kawasaki and its new 250. But practice sessions with the new bikes were proving disappointing. Ron Pierce was elected to fill in for the injured Jim Evans on his 250, and Ron seemed to be getting around faster than DuHamel.

Ron was shocked when he learned that the bike had seven speeds; he had been using only six.

Gary Scott on the strong 250 H-D was a threat, as was Yamaha-mounted Steve Baker. Last year’s winner, Don Castro, also looked tough. But no one was betting against Roberts, who, living up to the predictions, walked off and hid from the field. Scott and Baker had a tight race going most of the 100-mile distance, with Gary’s H-D eventually getting the upper hand.

There were plenty of machines and riders on hand for the production races. The 350 was dominated, of course, by Yamahas, though there were other brands. . .even a Moto Morini. California rider Bob Tigert took the win, making his long trip from the coast worthwhile. Big-bore ZI Kawasakis led the ultra-hot BMWs home this time, a switch from their defeat at Ontario. Dave Aldana, with his AMA license suspension repealed, and wearing his skeleton leathers, wobbled his way to the winner’s circle. Watching David heave that 900 Kawasaki into the corners was a treat.

But the real treat is the 200. That’s why so many people took vacations, made excuses to their bosses, drained bank accounts, used up sick leave, stretched expense budgets and laid all those plans for. . .the big one.

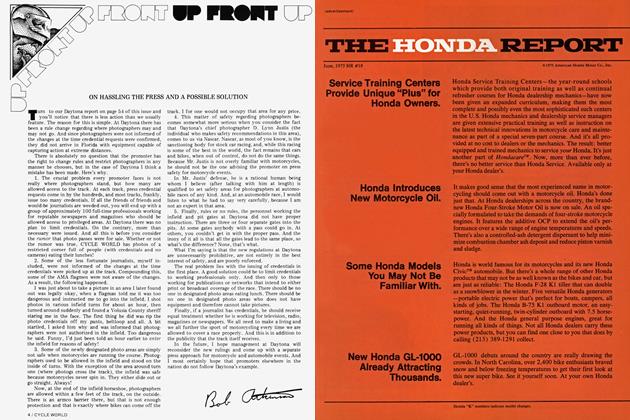

When the flag dropped, 72 riders swept away in three waves; 67,000 people watched as third-fastest qualifier and front-row-sitter Johnny Cecotto was pulled off the grid due to a stuck float in one of his carbs. The bike was pouring gas on the grid and the mechanics had to work fast to change a plug and push him down into the 73rd starting slot.

Tepi Lansivuori rocketed his Suzuki into a strong early lead and looked to be pulling away. Roberts ticked in for 2nd, chased at a distance by Agostini. There was a tremendous amount of pressure on the Suzuki ace from Finland, as Tepi more or less inherited the team’s number one spot when Sheene and Nixon couldn’t ride.

Roberts finally got hooked up on lap three and by the end of lap four had not only caught the lead Suzuki, but started running incredibly fast lap times and really put ground between himself and 2nd place. DuHamel had been running in the top ten, but went out on lap seven when his shifting shaft broke.

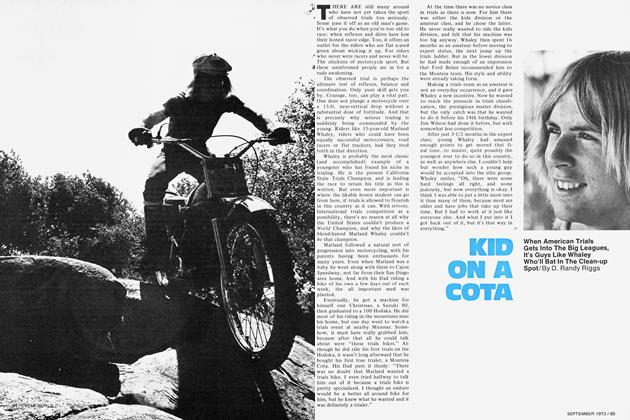

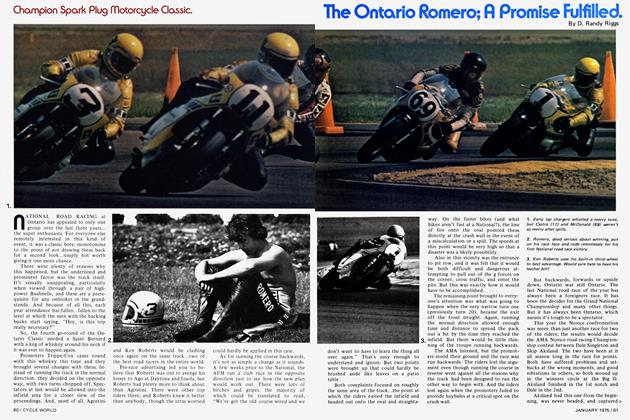

Cecotto, meanwhile, was making a charge through the pack unexcelled by any other ride in Daytona memory. In just 12 short laps he had moved to 7th, and by the time Roberts had dropped out on lap 15 with a ruined clutch, he was even closer to the leaders.

First gas stops started taking place just after Roberts’ exit from the race; in fact, there was some concern that his broken machine would be in the way of Romero, who pitted just seconds later.

The leaders went in and out quickly, but Lansivuori couldn’t make it clear that his chain was loose (he speaks no English). Two laps later he was in again; this time he got the idea across when he reached down and yanked his chain up and down. Chain tension plagued the Suzuki camp because of the new longertravel rear suspension.

Tepi lost a lap in the pits and the effort to make it back up was too much. He spilled in one of the slower turns, taking himself out of the war. Again his problem with the English language surfaced. The ambulance attendants thought he indicated he was okay, when in fact Tepi was telling them he took a hell of a bruising. They left him there to spectate and mull over his plans.

(Continued on page 76)

Continued from page 58

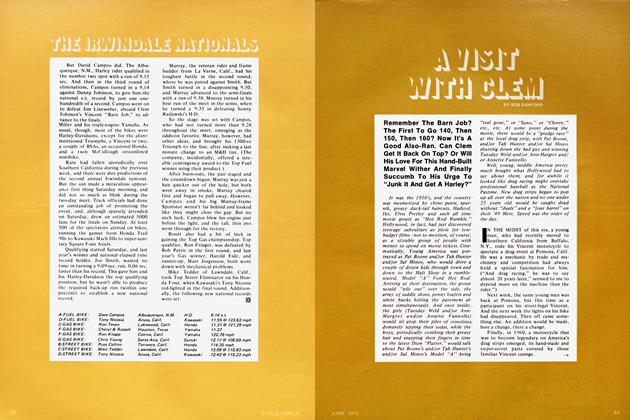

By this time riders had sorted themselves out pretty well, and three of the fastest, excepting the Cecotto Express, were McLaughlin, Steve Baker and Romero. McLaughlin was riding the race of his life, beautifully smooth, exceptionally fast. But it was not to last. Going into turn six, Steve lost the front end and skidded down on his side, relinquishing the precious lead to Romero. McLaughlin was not yet through, and in a beautiful display of iron-fisted determination, got the private Yamaha 700 underway again and took off after the leaders, down in 5th position.

Riding without a fairing bubble must have been incredibly hard on the neck muscles, but Steve never gave up for an instant. That was pure moxie from a man who should be under someone’s factory contract.

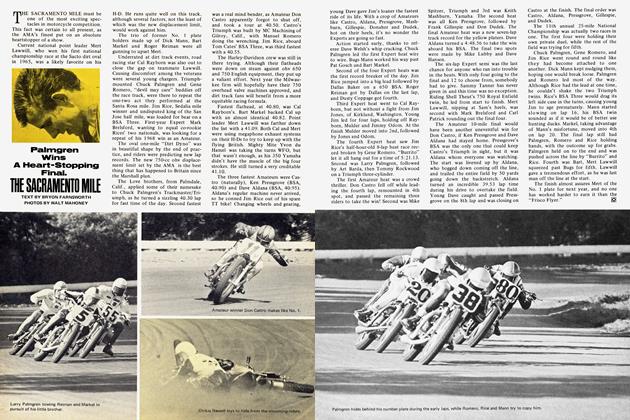

Baker took over the lead briefly as Gene pitted for fuel; most pit work was extremely quick this year, even by the privateer teams.

Agostini was simply outclassed this time around, and couldn’t seem to motor at his peak. All the Kawasakis went out with various troubles, from expansion chamber ills to transmission malfunctions. And Suzuki joined them with the crying towels. Best laid plans and Daytona simply do not mix.

Near the finish Romero was unstoppable, he’s been 2nd too often here. The race was between Ago and Cecotto at that point. . .and Cecotto was reeling him in like a dead fish. David Aldana had been circulating his Suzuki in 9th or 10th position most of the event, but at one of his gas stops fuel had been poured over his leathers and his skin was really burning. Don Castro had some difficulty too. With his chin down on the tank, a hard bump had nearly knocked his teeth out; and he was bothered with watering eyes for several laps.

Cecotto passed Ago with two laps to go, the crowd bellowing its enthusiasm. Romero coasted home with 18 seconds to spare, the win worth about $1000 for each of those 18 seconds. Baker hung in for 2nd; the brilliant Cecotto was 3rd after starting dead last. And had he started from the front row. . .what might we have witnessed?

Suzuki’s woes continued after the race was over. Aldana hung an immediate U-turn for the pits after crossing the finish line to get his fuel-soaked leathers off his skin. But scorers had screwed up somewhere and credited him with 28th place. Team manager Wright was off getting Tepi taken care of at the infield hospital after he had been left by the ambulance crew, and had walked back to the pits after the race. Aldana was concerned with his burns and had no chance to check the results sheet posted after the race. Had he seen the error he could have filed a protest within the half-hour protest period limit. But he was assuming that the team manager was checking the lists like he normally would; only in this case the manager was looking after the well-being of one of his riders. Even though you’ll not see Aldana’s name on the results sheets. . .he was in the top ten. Remember that, even if it doesn’t show in the results.

And remember Johnny Cecotto; you’ll see more of him soon. And Kenny’s hard to forget, it might have been his race without the clutch problem. Steve McLaughlin? One of the fastest riders anywhere. . .his get-off was a rare one and surprising. Course, we can’t forget ol’ Gene, the man without the Monoshock, the man who’s supposed to be a dirt tracker, the man who stomps the best laid plans into submission. El

RESULTS

HEAV WEIGHT CLASSES

View Full Issue

View Full Issue