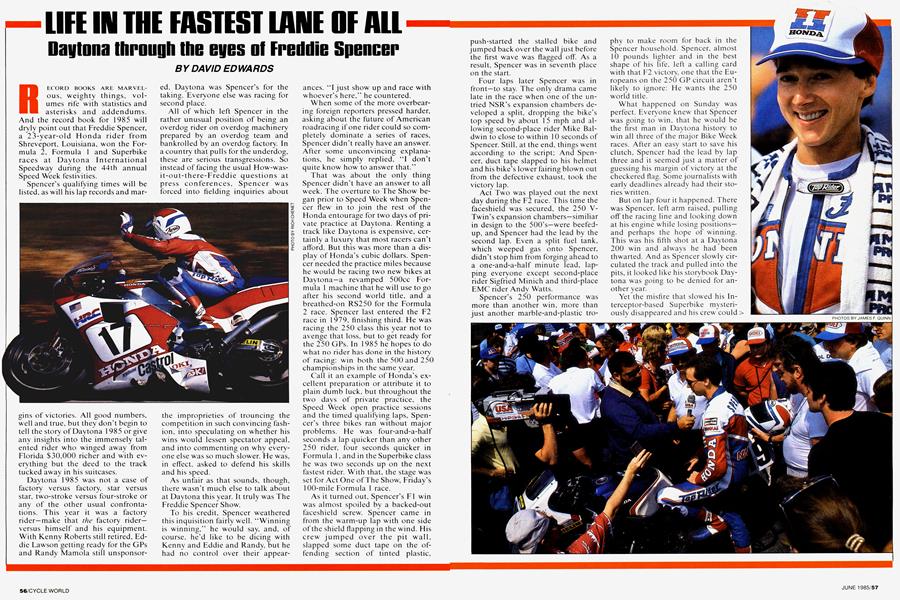

LIFE IN THE FASTEST LANE OF ALL

Daytona through the eyes 0f Freddie Spencer

DAVID EDWARDS

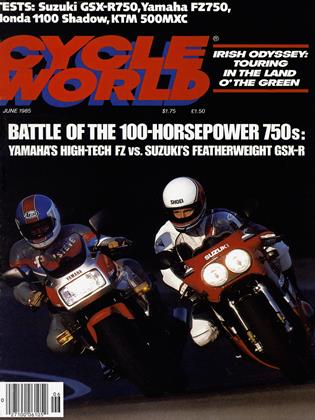

RECORD BOOKS ARE MARELous, weighty things, volumes rife with statistics, and asterisks and addendums, And the record book for 1985 will dryly point out that Freddie Spencer, a 23-year-old Honda rider from Shreveport, Louisiana, won the Formula 2, Formula 1 and Superbike races at Daytona International Speedway during the 44th annual Speed Week festivities.

Spencer’s qualifying times will be listed, as will his lap records and mar-

gins of victories. All good numbers, well and true, but they don’t begin to tell the story of Daytona 1985 or give any insights into the immensely talented rider who winged away from Florida $30,000 richer and with everything but the deed to the track tucked away in his suitcases.

Daytona 1985 was not a case of factory versus factory, star versus star, two-stroke versus four-stroke or any of the other usual confrontations. This year it was a factory rider—make that the factory rider— versus himself and his equipment. With Kenny Roberts still retired, Eddie Lawson getting ready for the GPs and Randy Mamola still unsponsored, Daytona was Spencer’s for the taking. Everyone else was racing for second place.

All of which left Spencer in the rather unusual position of being an overdog rider on overdog machinery prepared by an overdog team and bankrolled by an overdog factory. In a country that pulls for the underdog, these are serious transgressions. So instead of facing the usual How-wasit-out-there-Freddie questions at press conferences, Spencer was forced into fielding inquiries about the improprieties of trouncing the competition in such convincing fashion, into speculating on whether his wins would lessen spectator appeal, and into commenting on why everyone else was so much slower. He was, in effect, asked to defend his skills and his speed.

As unfair as that sounds, though, there wasn’t much else to talk about at Daytona this year. It truly was The Freddie Spencer Show.

To his credit, Spencer weathered this inquisition fairly well. “Winning is winning,” he would say, and, of course, he’d like to be dicing with Kenny and Eddie and Randy, but he had no control over their appearances. “I just show up and race with whoever’s here,” he countered.

When some of the more overbearing foreign reporters pressed harder, asking about the future of American roadracing if one rider could so completely dominate a series of races, Spencer didn’t really have an answer. After some unconvincing explanations, he simply replied, “I don’t quite know how to answer that.”

That was about the only thing Spencer didn’t have an answer to all week. The overture to The Show began prior to Speed Week when Spencer flew in to join the rest of the Honda entourage for two days of private practice at Daytona. Renting a track like Daytona is expensive, certainly a luxury that most racers can’t afford. But this was more than a display of Honda's cubic dollars. Spencer needed the practice miles because he would be racing two new bikes at Daytona—a revamped 500cc Formula 1 machine that he will use to go after his second world title, and a breathed-on RS250 for the Formula 2 race. Spencer last entered the F2 race in 1979, finishing third. He was racing the 250 class this year not to avenge that loss, but to get ready for the 250 GPs. In 1985 he hopes to do what no rider has done in the history of racing: win both the 500 and 250 championships in the same year.

Call it an example of Honda’s excellent preparation or attribute it to plain dumb luck, but throughout the two days of private practice, the Speed Week open practice sessions and the timed qualifying laps, Spencer’s three bikes ran without major problems. He was four-and-a-half seconds a lap quicker than any other 250 rider, four seconds quicker in Formula 1, and in the Superbike class he was two seconds up on the next fastest rider. With that, the stage was set for Act One of The Show, Friday’s 100-mile Formula 1 race.

As it turned out, Spencer’s FI win was almost spoiled by a backed-out faceshield screw. Spencer came in from the warm-up lap with one side of the shield flapping in the wind. His crew jumped over the pit wall, slapped some duct tape on the offending section of tinted plastic, push-started the stalled bike and jumped back over the wall just before the first wave was flagged off. As a result, Spencer was in seventh place on the start.

Four laps later Spencer was in front—to stay. The only drama came late in the race when one of the untried NSR’s expansion chambers developed a split, dropping the bike’s top speed by about 15 mph and allowing second-place rider Mike Baldwin to close to within 10 seconds of Spencer. Still, at the end, things went according to the script; And Spencer, duct tape slapped to his helmet and his bike’s lower fairing blown out from the defective exhaust, took the victory lap.

Act Two was played out the next day during the F2 race. This time the faceshield was secured, the 250 VTwin’s expansion chambers—similiar in design to the 500's—were beefedup, and Spencer had the lead by the second lap. Even a split fuel tank, which weeped gas onto Spencer, didn’t stop him from forging ahead to a one-and-a-half minute lead, lapping everyone except second-place rider Sigfried Minich and third-place EMC rider Andy Watts.

Spencer’s 250 performance was more than another win, more than just another marble-and-plastic trophy to make room for back in the Spencer household. Spencer, almost 10 pounds lighter and in the best shape of his life, left a calling card with that F2 victory, one that the Europeans on the 250 GP circuit aren’t likely to ignore: He wants the 250 world title.

What happened on Sunday was perfect. Everyone knew that Spencer was going to win. that he would be the first man in Daytona history to win all three of the major Bike Week races. After an easy start to save his clutch, Spencer had the lead by lap three and it seemed just a matter of guessing his margin of victory at the checkered flag. Some journalists with early deadlines already had their stories written.

But on lap four it happened. There was Spencer, left arm raised, pulling off the racing line and looking down at his engine while losing positions— and perhaps the hope of winning. This was his fifth shot at a Daytona 200 win and always he had been thwarted. And as Spencer slowly circulated the track and pulled into the pits, it looked like his storybook Daytona was going to be denied for another year.

Yet the misfire that slowed his Interceptor-based Superbike mysteriously disappeared and his crew could > find nothing wrong. Spencer rejoined the fray and almost two minutes behind leader Wes Cooley.

Freddie Spencer has been called many things in his racing career, a career that started 1 7 years ago when at age 6 he was lifted onto the seat of his first racing motorcycle. People have referred to him as a gentleman, the complete professional, devoutly religious, a press agent’s dream and, compared to other, more-charismatic racers, perhaps a little boring. But no one has ever denied that Freddie Spencer is a racer first and foremost, in some eyes the best ever.

There was no panic in Spencer as he started his long climb back to the top position. The eyes behind the gray faceshield focused a little harder, the body in the red, white and blue leathers crouched just a little lower over the fuel tank, the braking points got deeper, the throttle was opened earlier.

An hour before the Superbike race, a very calm Spencer had been asked how he handled the pressures of racing. “1 know' exactly what I can do,” he said. “I know my own abilities. Nobody is harder on me than myself;

I expect more out of me than anybody else does. I always do the best that I can, and if that's not enough, well, it’s not enough.”

On this sunny March day in Florida, Spencer’s best was more than enough. Riding at what he would later describe as a “comfortable” pace, he picked up as much as five seconds a lap on the leaders, and just past the race’s halfway point, he went into the lead. He lost it when he came in for gas and to get his overworked rear tire changed, but three laps later he was in the lead again, eventually stretching his lead over Cooley to almost one-and-a-half minutes.

Following the checkered flag came a familiar scene at Daytona 1985; Spencer taking a parade lap, waving to the fans, then pulling into victory lane, kissing his long-time girlfriend Sari and telling, for the first of many times, how' he did it.

The press conference after the race was vintage Spencer. He sat before the assembled reporters, smiling and eyes twinkling. He answered each question in careful, measured phrases, expounded on each question. Spencer is a marvel at press con-

ferences, especially for someone who as a student was too shy to stand up in class and answer the teacher. Spencer is still shy enough not to brag, still respectful enough to compliment his fellow racers, still humble enough to chalk up his victories to luck and good preparation rather than to his abilities alone. There are no expletives that later have to be deleted, no juicy frontpage quotes.

But listen around the edges, and Spencer the racer is visible behind Spencer the record-book wonder and Spencer the press agent’s dream. One reporter, perhaps remembering Kenny Roberts’ aborted 250 title attempt in 1978, asked Spencer when the decision would come to pass on the 250s and concentrate on the more-prestigious 500s. Spencer replied that the 500 title w'as, of course, the important one, and that he hoped it wouldn't come down to making a decision to go after just one title. But somewhere in that textbook reply came an unguarded statement, out of character and more telling that any that had come before.

“I want it all,” said Freddie Spencer. ®

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

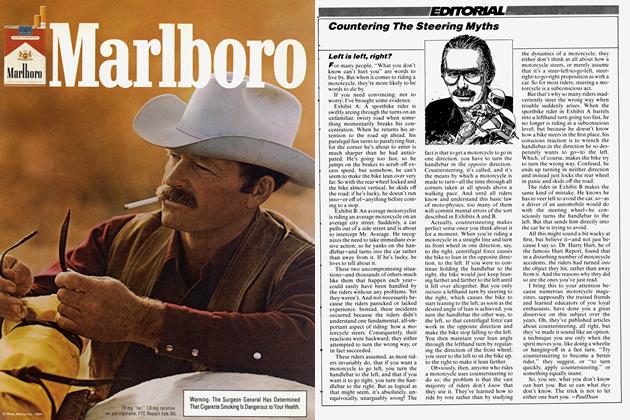

Editorial

EditorialCountering the Steering Myths

June 1985 By Pauldean -

At Large

At LargeInside the Accidental Fortress

June 1985 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1985 -

Rounup

RounupLand Closure: the Fight For the Open Range

June 1985 By David Edwards -

Roundup

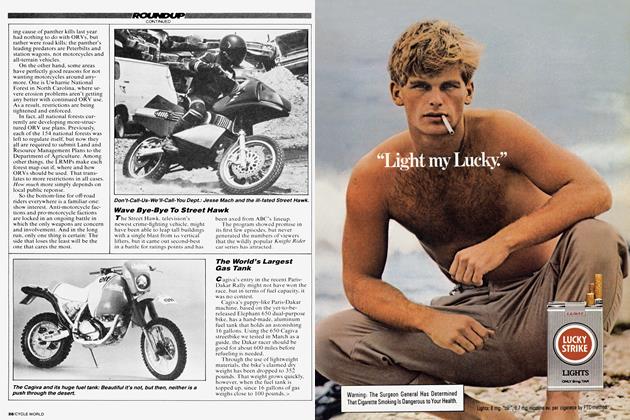

RoundupWave Bye-Bye To Street Hawk

June 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupThe World's Largest Gas Tank

June 1985