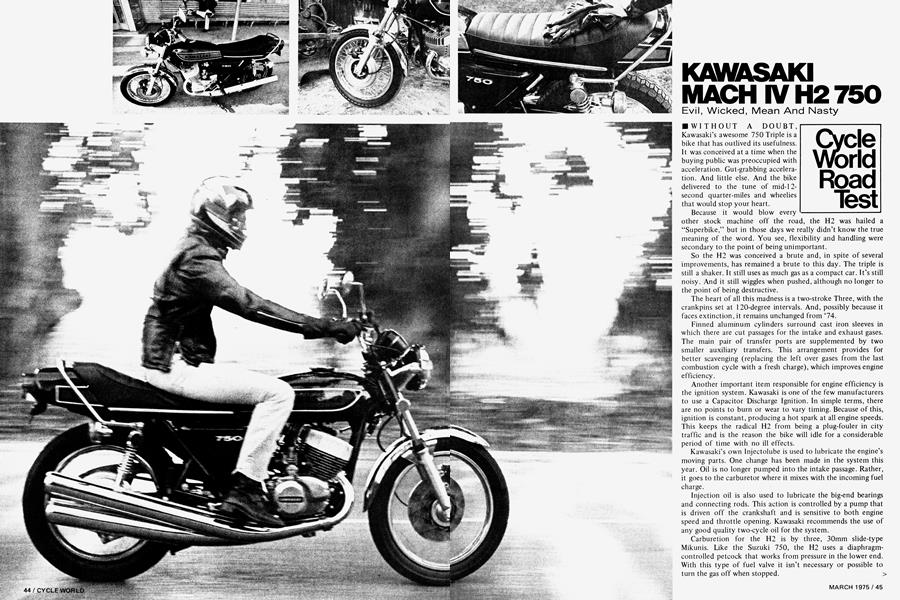

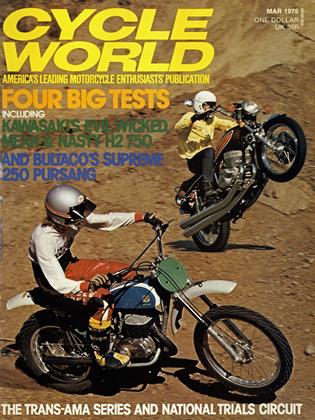

KAWASAKI MACH IV H2 750

Cycle World Road Test

Evil, Wicked, Mean And Nasty

WITHOUT A DOUBT, Kawasaki’s awesome 750 Triple is a bike that has outlived its usefulness. It was conceived at a time when the buying public was preoccupied with acceleration. Gut-grabbing acceleration. And little else. And the bike delivered to the tune of mid-12second quarter-miles and wheelies that would stop your heart.

Because it would blow every other stock machine off the road, the H2 was hailed a “Superbike,” but in those days we really didn’t know the true meaning of the word. You see, flexibility and handling were secondary to the point of being unimportant.

So the H2 was conceived a brute and, in spite of several improvements, has remained a brute to this day. The triple is still a shaker. It still uses as much gas as a compact car. It’s still noisy. And it still wiggles when pushed, although no longer to the point of being destructive.

The heart of all this madness is a two-stroke Three, with the crankpins set at 120-degree intervals. And, possibly because it faces extinction, it remains unchanged from ‘74.

Finned aluminum cylinders surround cast iron sleeves in which there are cut passages for the intake and exhaust gases. The main pair of transfer ports are supplemented by two smaller auxiliary transfers. This arrangement provides for better scavenging (replacing the left over gases from the last combustion cycle with a fresh charge), which improves engine efficiency.

Another important item responsible for engine efficiency is the ignition system. Kawasaki is one of the few manufacturers to use a Capacitor Discharge Ignition. In simple terms, there are no points to burn or wear to vary timing. Because of this, ignition is constant, producing a hot spark at all engine speeds. This keeps the radical H2 from being a plug-fouler in city traffic and is the reason the bike will idle for a considerable period of time with no ill effects.

Kawasaki’s own Injectolube is used to lubricate the engine’s moving parts. One change has been made in the system this year. Oil is no longer pumped into the intake passage. Rather, it goes to the carburetor where it mixes with the incoming fuel charge.

Injection oil is also used to lubricate the big-end bearings and connecting rods. This action is controlled by a pump that is driven off the crankshaft and is sensitive to both engine speed and throttle opening. Kawasaki recommends the use of any good quality two-cycle oil for the system.

Carburetion for the H2 is by three, 30mm slide-type Mikunis. Like the Suzuki 750, the H2 uses a diaphragmcontrolled petcock that works from pressure in the lower end. With this type of fuel valve it isn’t necessary or possible to turn the gas off when stopped. >

A push-type of starter lever is mounted on the left side of the bars. For cold starts, the lever is pushed to the limit of its travel by the left thumb. Several kicks (generally two) on the starter and the engine rattles to life.

Starting sounds easy and it is, to an extent. We say to an extent because the procedure before and after is a pain. First, the right peg must be folded up to clear the kickstarter. The starter is long, which makes it high and difficult to get your foot on if the bike isn’t on one of the two stands. There is no primary kickstarting, so the transmission must be in neutral before going any farther. And once started, the lever must be folded in and the footpeg must be returned to the riding position.

Neutral, however, is easy to find on the H2. In fact, finding it requires no finesse at all. Just step down on the shift lever until it doesn’t move anymore. That’s right. Neutral is at the bottom of the shift pattern.

As we see it, this can be a real disadvantage. Have you ever needed to get into first gear fast and found yourself in neutral? If this happens in the middle of a fast, tight turn, things get exciting to say the least.

Warm up is quick on the H2, so you don’t have to wait around much before you can leave; but a rather high overall gear ratio makes it difficult to get off the line or away from a stop without gassing it. If you can’t leave quickly, you’ve got to slip the clutch and play with the throttle.

Once moving at slower speeds—like in traffic—or while coasting with partial throttle, there is an enormous amount of surge. Sometimes it’s bad enough to force you to clutch the engine. And it’s inherent in the H2 because you can’t get proper flow through large ports at low rpm and/or small throttle openings.

What takes the place of the surge at around 4000 rpm is even more annoying. Vibration. And it’s bad. . .bad enough in the footpegs and handlebars to put your hands and feet to sleep. At 6000 rpm, the bars shake so severely that it’s difficult to hang on very long. It’s almost like a big-bore vertical Twin in this respect.

The factory attempted to solve the problem by rubbermounting the engine on their prototypes, much like Norton did to cure the shakes in their vertical Twin. The curious thing about this attempted fix is that it worked for Norton, but not for Kawasaki. So rubber-mounting has never seen production on the H2.

Surge and vibration remain unchecked, but the Three’s noise level is down and the unit’s ability to nurse a gallon of gas is up. Lower noise was achieved in ‘73 by fitting more restrictive mufflers and by redesigning the air intake system. This in turn has cut down the engine’s breathing and exhaust efficiency and that is the reason for a decrease in fuel consumption from 19-23 miles per gallon to something in the neighborhood of 26 mpg.

A quieter more economical engine is also one that produces less power and less power has taken the H2 out of the 12-second bracket at the drags. Low 13s are still possible and the motor delights in doing them, as it always has. Running the H2 Three wide open, going up through the gears, is really the only thing the engine does in a flawless manner. In every other situation it’s awkward, perhaps even annoying, and today that really isn’t necessary.

The three-cylinder power plant then has benefited little > over the years. But there’s no question that, overall, the ‘75 H2 is a better motorcycle; better because a chassis improvement has made the machine safe. The swinging arm is now two inches longer, stretching the wheelbase to 57.5 in., with the rear axle centered in relation to its fore/aft adjustment. And this has turned the original model’s deadly wobble into an acceptable wiggle that warns the rider when the limit has been reached.

PARTS PRICING

$29.50

The main frame loop remains a double cradle design that is more or less the norm for the majority of bikes today. The H2, however, does sport unusual geometry, which affects lowspeed riding somewhat. Fork angle is a steep 26.5 degrees. We would expect to find this steering geometry on a short tracker weighing several hundred pounds less. This angle, and a seemingly high center of gravity, magnifies the weight on the front wheel. This makes the H2 feel sluggish and heavy on the front end when weaving through city traffic.

Cruising stability is built into the design with four inches of trail. Anywhere from 35 mph on up, the bike tracks straight. In fact, it is fairly pleasant at the national maximum speed of 55 mph. A slightly wider seat and softer suspension would help, but all in all it’s not bad. And the engine is between its surge and vibration points, so it doesn’t detract from the ride.

Cornering the H2 at posted limits presents no problem whatsoever. Contrary to popular belief, frame flex at these speeds or in reasonable excess of them does not exist. Nothing evil occurs. In addition, the H2 doesn’t have a tendency to drag stands and pipes on the ground. These parts are well tucked in and won’t scrape unless the rider is completely out of control.

Other factors aiding the H2’s handling and safety margin are excellent traction offered by the Dunlop Gold Seal tires and a strong set of brakes. Under the extreme conditions of repeated 100-mph stops, there was little fade from the hydraulic front disc. And the internal expanding rear unit lost no more braking force than the norm.

So the H2 is a well-behaved handler at the sane speeds most riders will subject it to. But what if your ability exceeds the bike’s limit and what if you berserk it? Well, when you reach the bike’s limit, that wiggle we mentioned earlier crops up.

The frame has something to do with this, but most of the blame can be placed on the suspension units. As usual, the rear shocks suffer from lack of travel, stiff springs and poor damping control. The front forks have adequate travel, but the action is too stiff. Small bumps, holes, frost heaves, or washboard chatter is driven up through the frame and delivered to the rider full force. When the Gs from cornering or the bumps in the road bottom the rear shocks, the bike wiggles. Go any faster or hit a bump that’s just a little larger, and you are not only going to have your hands full, but there’s an excellent possibility you’ll experience gravel rash first hand.

Dangerous is no longer a good word for the H2 because it’s not; even though there are bikes around that can exceed its cornering ability. Irony is a good word though, because one of the bikes that will out-corner the H2 is the Z1 (also manufactured by Kawasaki). And the Z1 will blow the H2 off at the drags without the ills of surging, vibration and poor mileage.

The king of superbikes is simply no longer king. Worse yet, its very existence is threatened by a sometimes unrealistic Environmental Protection Agency and government preoccupation with noise pollution.

Time has dictated that a change is due. Perhaps overdue. And in a way that’s sad because brute power machines like the H2 turned a lot of people on at a time when all of us could afford to be carefree. 0

KAWASAKI MACH IV H2 750

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontA New Column For Dirt Riders, A Note On the Cycle World Show, And A European-Style Gp In the U.S.?

March 1975 -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1975 -

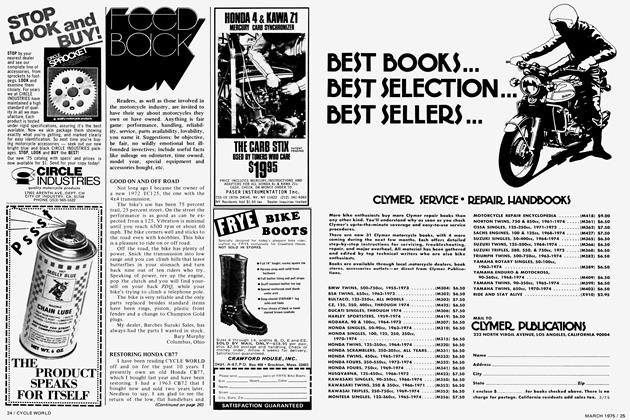

Departments

DepartmentsFeedback

March 1975 -

Departments

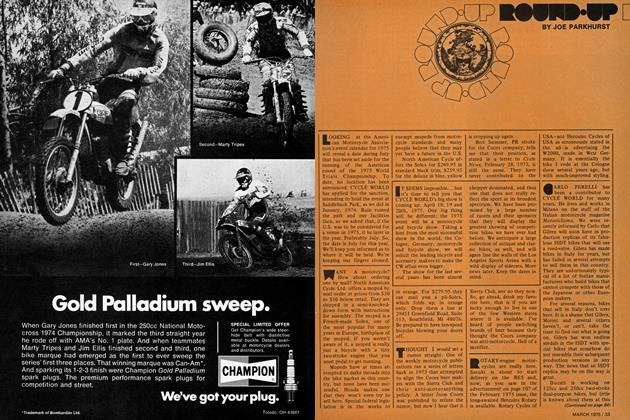

DepartmentsRound Up

March 1975 By Joe Parkhurst -

Features

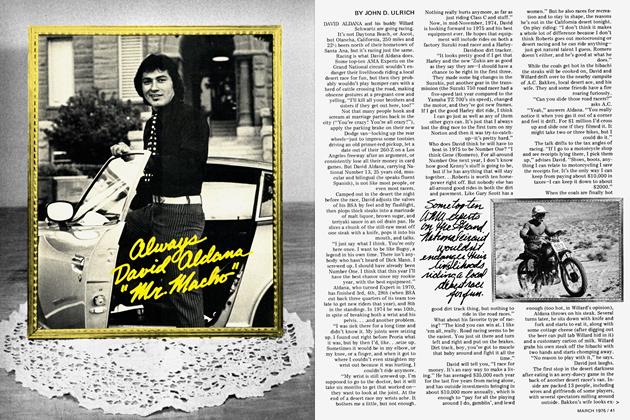

FeaturesAlways David Aldana "Mr. Macho"

March 1975 By John D. Ulrich -

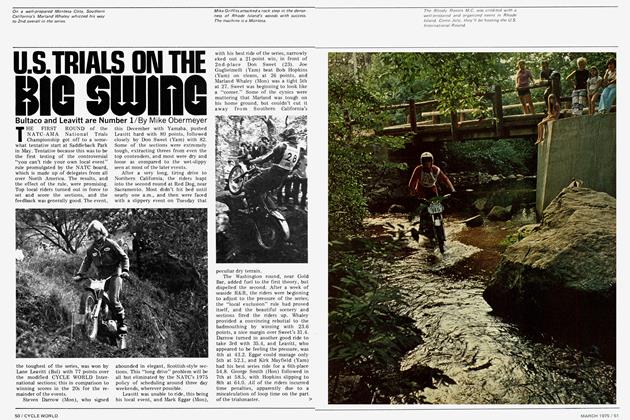

Competition

CompetitionU.S. Trials On the Big Swing

March 1975 By Mike Obermeyer