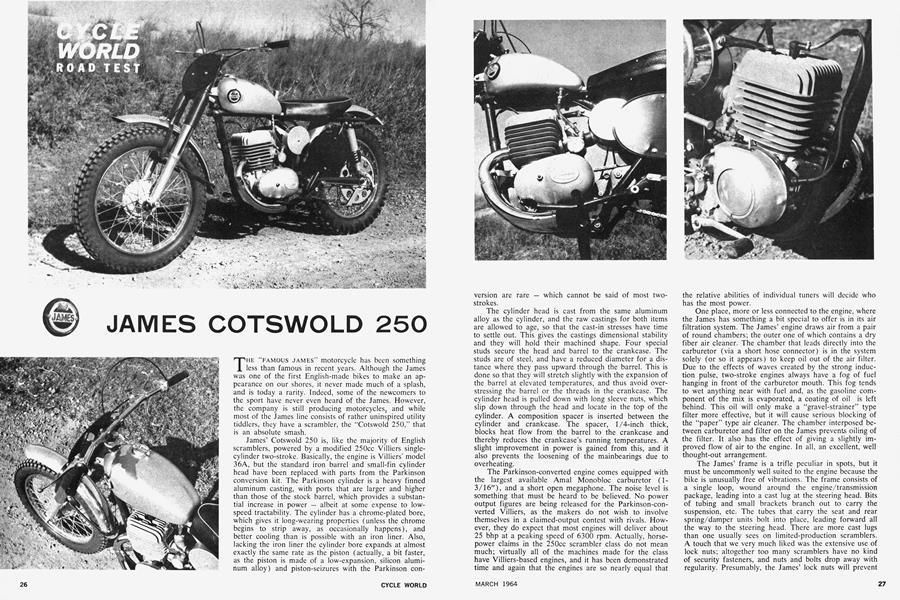

JAMES COTSWOLD 250

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

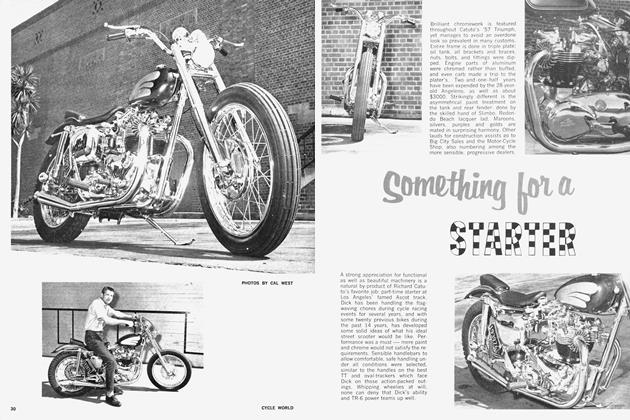

THE “FAMOUS JAMES’’ motorcycle has been something less than famous in recent years. Although the James was one of the first English-made bikes to make an appearance on our shores, it never made much of a splash, and is today a rarity. Indeed, some of the newcomers to the sport have never even heard of the James. However, the company is still producing motorcycles, and while most of the James line consists of rather uninspired utility tiddlers, they have a scrambler, the “Cotswold 250,“ that is an absolute smash.

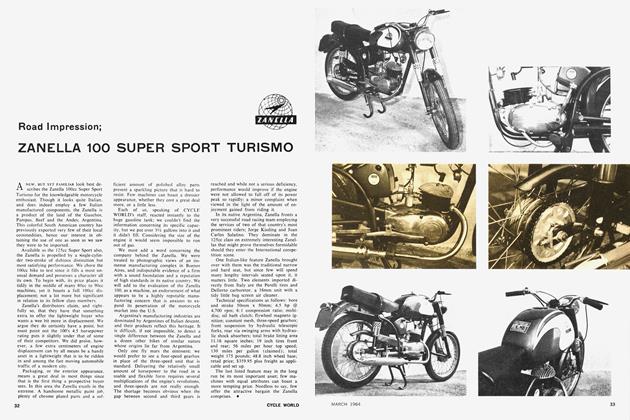

James’ Cotswold 250 is, like the majority of English scramblers, powered by a modified 250cc Villiers singlecylinder two-stroke. Basically, the engine is Villiers’ model 36A, but the standard iron barrel and small-fin cylinder head have been replaced with parts from the Parkinson conversion kit. The Parkinson cylinder is a heavy finned aluminum casting, with ports that are larger and higher than those of the stock barrel, which provides a substantial increase in power — albeit at some expense to lowspeed tractability. The cylinder has a chrome-plated bore, which gives it long-wearing properties (unless the chrome begins to strip away, as occasionally happens), and better cooling than is possible with an iron liner. Also, lacking the iron liner the cylinder bore expands at almost exactly the same rate as the piston (actually, a bit faster, as the piston is made of a low-expansion, silicon aluminum alloy) and piston-seizures with the Parkinson conversion are rare — which cannot be said of most twostrokes.

The cylinder head is cast from the same aluminum alloy as the cylinder, and the raw castings for both items are allowed to age, so that the cast-in stresses have time to settle out. This gives the castings dimensional stability and they will hold their machined shape. Four special studs secure the head and barrel to the crankcase. The studs are of steel, and have a reduced diameter for a distance where they pass upward through the barrel. This is done so that they will stretch slightly with the expansion of the barrel at elevated temperatures, and thus avoid overstressing the barrel or the threads in the crankcase. The cylinder head is pulled down with long sleeve nuts, which slip down through the head and locate in the top of the cylinder. A composition spacer is inserted between the cylinder and crankcase. The spacer, 1/4-inch thick, blocks heat flow from the barrel to the crankcase and thereby reduces the crankcase’s running temperatures. A slight improvement in power is gained from this, and it also prevents the loosening of the mainbearings due to overheating.

The Parkinson-converted engine comes equipped with the largest available Amal Monobloc carburetor (13/16"), and a short open megaphone. The noise level is something that must be heard to be believed. No power output figures are being released for the Parkinson-converted Villiers, as the makers do not wish to involve themselves in a claimed-output contest with rivals. However, they do expect that most engines will deliver about 25 bhp at a peaking speed of 6300 rpm. Actually, horsepower claims in the 250cc scrambler class do not mean much; virtually all of the machines made for the class have Villiers-based engines, and it has been demonstrated time and again that the engines are so nearly equal that the relative abilities of individual tuners will decide who has the most power.

One place, more or less connected to the engine, where the James has something a bit special to offer is in its air filtration system. The James’ engine draws air from a pair of round chambers; the outer one of which contains a dry fiber air cleaner. The chamber that leads directly into the carburetor (via a short hose connector) is in the system solely (or so it appears) to keep oil out of the air filter. Due to the effects of waves created by the strong induction pulse, two-stroke engines always have a fog of fuel hanging in front of the carburetor mouth. This fog tends to wet anything near with fuel and, as the gasoline component of the mix is evaporated, a coating of oil is left behind. This oil will only make a “gravel-strainer” type filter more effective, but it will cause serious blocking of the “paper” type air cleaner. The chamber interposed between carburetor and filter on the James prevents oiling of the filter. It also has the effect of giving a slightly improved flow of air to the engine. In all, an excellent, well thought-out arrangement.

The James’ frame is a trifle peculiar in spots, but it must be uncommonly well suited to the engine because the bike is unusually free of vibrations. The frame consists of a single loop, wound around the engine/transmission package, leading into a cast lug at the steering head. Bits of tubing and small brackets branch out to carry the suspension, etc. The tubes that carry the seat and rear spring/damper units bolt into place, leading forward all the way to the steering head. There are more cast lugs than one usually sees on limited-production scramblers. A touch that we very much liked was the extensive use of lock nuts; altogether too many scramblers have no kind of security fasteners, and nuts and bolts drop away with regularity. Presumably, the James’ lock nuts will prevent that from happening.

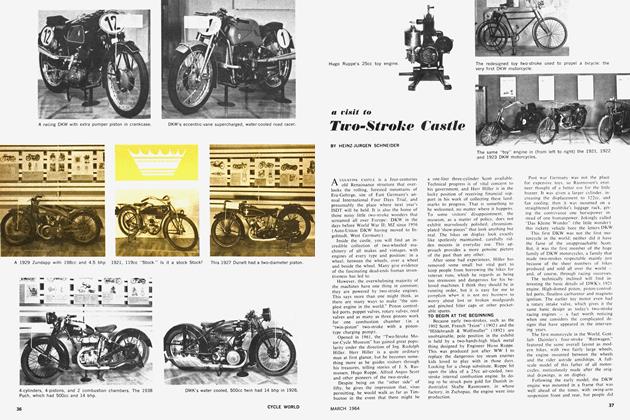

Unlike most of the other English lightweight scramblers, which have link-type forks, the James has telescopic forks. These are Norton’s Roadholder forks, but modified to become “Dirtholders.” We do not know precisely what was done to the Norton forks, but from appearance and performance it would seem that they have been extended to give more travel on “bounce.” This has worked very well, and the forks seldom bottom. Unfortunately, in providing bounce, they have created some shortness of travel in rebound, and the forks will repeatedly extend right out to the stops (with a loud clank) when running over rough ground. Control is not affected, but the clattering is something of an annoyance.

The rear suspension offers nothing out of the ordinary in specification, but it does the job it has to do in a way that leaves no room for criticism. The damping is good, and the springs felt just exactly stiff enough. Riders of different weights can set the suspension for height by means of a cam-type adjuster incorporated in each spring/ damper unit. The only noteworthy item in the rear suspension was the swing arm pivot arrangement, which used bonded rubber bushings in place of the usual bronze. In theory, these rubber bushings should make the swing arm a bit wobbly, but in point of fact the arrangement felt quite solid — and rubber bushings do not require lubrication and are unaffected by severe dust conditions.

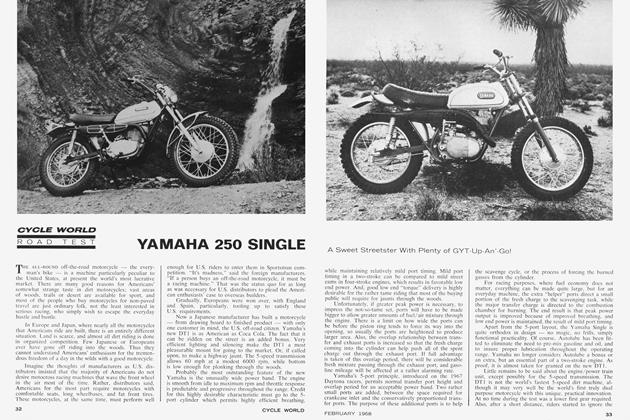

For some reason, both short and tall riders on our staff felt very much at home astride the James. One complainer remarked that the seat was a smidgin high, but then you can't please everyone. The bars were wide and flat, and gave much more leverage than the bike’s light steering actually required. The control levers had ball ends, as is now often required by regulation, and the cables were adjustable, by hand, at the levers. Oddly enough, the footpegs were non-folding, which can be decidedly dangerous at times. We would recommend that the factory substitute folding pegs or, that failing, the buyer make the change before he goes racing. Whenever and by whomever the change is made, do not change the peg position; it is perfect (from the standpoint of comfort). Racing riders may want to relocate the pegs in the interest of handling. The James is a trifle nose-heavy, for a scrambler, and it would be better in really rough going if its rider could get more weight on the rear wheel and float the front wheel over the bumps. More weight at the rear might also overcome the James’ tendency to pitch when charging across choppy ground.

Pitch or no pitch, the James may very well be the best handling scrambler we have ever tried. The steering is quick, and though experiences with other bikes having quick steering made us cautious at first, we quickly discovered that with the James, the steering is not really so much quick as it is light; the rider simply doesn’t have to use as much muscle as is usually required. Because the steering is good, and the seating position and controls ditto, a session of brush-bashing is a lot more fun than work. The only real control problem we encountered was with the shift, which was smooth and positive in action, but located too far from the footpeg to be a comfortable toc’s-reach for anything smaller than a size-12 foot.

During our tests, we did not have occasion to use the Cotswold’s brakes hard — and it is probably just as well that we did not. The James has generally superb handling, and a lot of power, but it also has the most puny set of brakes we have seen in a long while. The drums look for all the world like old snuff cans, and while we could be misjudging them, we do get the feeling that a good hot descent down some mountain trail would work them to the limit of their capacity. Of course, it is also true that in the scrambles racing for which the Cotswold is intended, the brakes will probably never be worked very hard in any case.

Apart from the excellent handling, there were many other things we liked about James’ Cotswold: the seat, for example, as it was one of the best we have tried. Another good point was the overall finish and appearance. Not much chrome is used, except on the exhaust pipe, wheel rims (which are of steel) and handlebars, but the good-qualitv paint and shiny aluminum-alloy fenders make the bike look quite good. The fuel tank is of steel, which has toughness to recommend it, if not lightness, and is fitted with a hinged filler cap that dogs down too tightly to leak and cannot be lost. Rim locks are provided to insure that the tires do not slip and pull out the valve stem, and the engine and transmission are protected by the frame and a bolt-on bash plate. Too, guards above and below the chain prevent the thing from winding itself around the rider’s neck.

Taking everything into the accounting, the James Cotswold 250 appeared to us to be one of the very best 250-class scramblers to be had today. Its shortcomings are few and relatively inconsequential, and its virtues are many. It gets a spot high on our list of “machines we would like to own.” •

JAMES COTSWOLD 250

$795

View Full Issue

View Full Issue