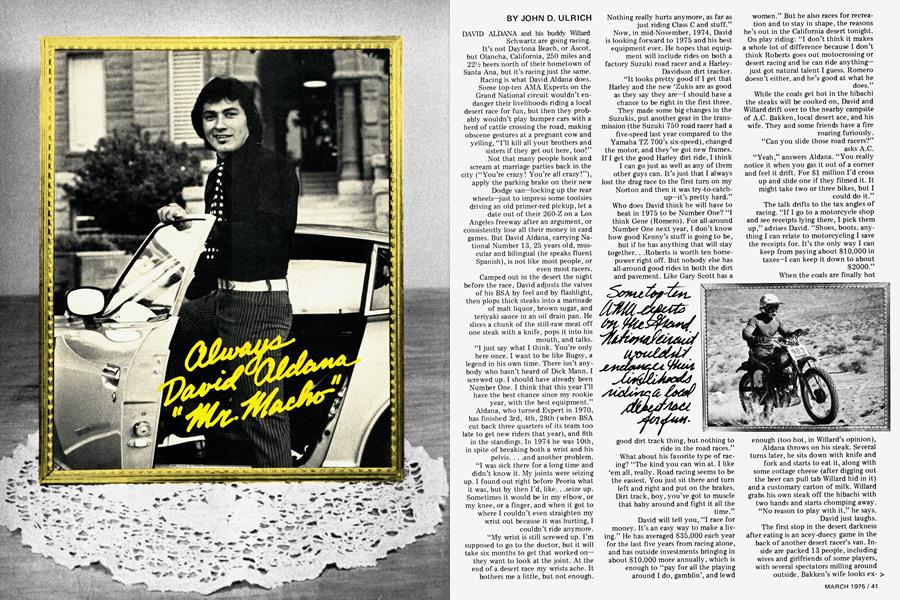

always David aldana "Mr. Macho"

JOHN D. ULRICH

DAVID ALDANA and his buddy Willard Schwartz are going racing. It’s not Daytona Beach, or Ascot, but Olancha, California, 250 miles and 22½ beers north of their hometown of Santa Ana, but it’s racing just the same. Racing is what David Aldana does. Some top-ten AMA Experts on the Grand National circuit wouldn’t endanger their livelihoods riding a local desert race for fun, but then they probably wouldn’t play bumper cars with a herd of cattle crossing the road, making obscene gestures at a pregnant cow and yelling, “I’ll kill all your brothers and sisters if they get out here, too!” Not that many people honk and scream at marriage parties back in the city (“You’re crazy! You’re all crazy!”), apply the parking brake on their new Dodge van—locking up the rear wheels—just to impress some tootsies driving an old primer-red pickup, let a date out of their 260-Z on a Los Angeles freeway after an argument, or consistently lose all their money in card games. But David Aldana, carrying National Number 13, 25 years old, muscular and bilingual (he speaks fluent Spanish), is not like most people, or even most racers.

Camped out in the desert the night before the race, David adjusts the valves of his BSA by feel and by flashlight, then plops thick steaks into a marinade of malt liquor, brown sugar, and teriyaki sauce in an oil drain pan. He slices a chunk of the still-raw meat off one steak with a knife, pops it into his mouth, and talks. “I just say what I think. You’re only here once. I want to be like Bugsy, a legend in his own time. There isn’t anybody who hasn’t heard of Dick Mann. I screwed up. I should have already been Number One. I think that this year I’ll have the best chance since my rookie year, with the best equipment.” Aldana, who turned Expert in 1970, has finished 3rd, 4th, 28th (when BSA cut back three quarters of its team too late to get new riders that year), and 8th in the standings. In 1974 he was 10th, in spite of breaking both a wrist and his pelvis. . . .and another problem. “I was sick there for a long time and didn’t know it. My joints were seizing up. I found out right before Peoria what it was, but by then I’d, like. . .seize up. Sometimes it would be in my elbow, or my knee, or a finger, and when it got to where I couldn’t even straighten my wrist out because it was hurting, I couldn’t ride anymore. “My wrist is still screwed up. I’m supposed to go to the doctor, but it will take six months to get that worked on— they want to look at the joint. At the end of a desert race my wrists ache. It bothers me a little, but not enough.

Nothing really hurts anymore, as far as just riding Class C and stuff.” Now, in mid-November, 1974, David is looking forward to 1975 and his best equipment ever. He hopes that equipment will include rides on both a factory Suzuki road racer and a Harley -Davidson dirt tracker.

“It looks pretty good if I get that Harley and the new ‘Zukis are as good as they say they are—I should have a chance to be right in the first three. They made some big changes in the Suzukis, put another gear in the transmission (the Suzuki 750 road racer had a five-speed last year compared to the Yamaha TZ 700’s six-speed), changed the motor, and they’ve got new frames. If I get the good Harley dirt ride, I think I can go just as well as any of them other guys can. It’s just that I always lost the drag race to the first turn on my Norton and then it was try-to-catchup—it’s pretty hard.” Who does David think he will have to beat in 1975 to be Number One? “I think Gene (Romero). For all-around Number One next year, I don’t know how good Kenny’s stuff is going to be, but if he has anything that will stay together. . .Roberts is worth ten horsepower right off. But nobody else has all-around good rides in both the dirt and pavement. Like Gary Scott has a

good dirt track thing, but nothing to ride in the road races.” What about his favorite type of racing? “The kind you can win at. I like ‘em all, really. Road racing seems to be the easiest. You just sit there and turn left and right and put on the brakes. Dirt track, boy, you’ve got to muscle that baby around and fight it all the

time.”

David will tell you, “I race for money. It’s an easy way to make a living.” He has averaged $35,000 each year for the last five years from racing alone, and has outside investments bringing in about $10,000 more annually, which is enough to “pay for all the playing around I do, gamblin’, and lewd

women.” But he also races for recreation and to stay in shape, the reasons he’s out in the California desert tonight.

On play riding: “I don’t think it makes a whole lot of difference because I don’t think Roberts goes out motocrossing or desert racing and he can ride anything— just got natural talent I guess. Romero doesn’t either, and he’s good at what he

does.”

While the coals get hot in the hibachi the steaks will be cooked on, David and Willard drift over to the nearby campsite of A.C. Bakken, local desert ace, and his wife. They and some friends have a fire roaring furiously. “Can you slide those road racers?”

asks A.C

“Yeah,” answers Aldana. “You really notice it when you gas it out of a corner and feel it drift. For $1 million I’d cross up and slide one if they filmed it. It might take two or three bikes, but I could do it.” The talk drifts to the tax angles of racing. “If I go to a motorcycle shop and see receipts lying there, I pick them up,” advises David. “Shoes, boots, anything I can relate to motorcycling I save the receipts for. It’s the only way I can keep from paying about $10,000 in taxes—I can keep it down to about

$2000.”

When the coals are finally hot

enough (too hot, in Willard’s opinion), Aldana throws on his steak. Several turns later, he sits down with knife and fork and starts to eat it, along with some cottage cheese (after digging out the beer can pull tab Willard hid in it) and a customary carton of milk. Willard grabs his own steak off the hibachi with two hands and starts chomping away. “No reason to play with it,” he says.

David just laughs. The first stop in the desert darkness after eating is an acey-duecy game in the back of another desert racer’s van. Inside are packed 13 people, including wives and girlfriends of some players, with several spectators milling around outside. Bakken’s wife looks exasperated, worried about him losing. David picks up a large metal ring and holds it up towards Bakken. “Here, this fell out of your nose, A.C. Your wife had it in her fingers. Heh heh.” A blonde girl, who keeps talking baby talk to Tom Brooks, attracts David’s attention as another player is quietly winning everyone’s money. “You talk some more so I can make more fun of you.” One comment draws a shocked look from the young lady and David mimics her odd speech. “Ohhhh, you’re so terrible. You’re so foul! Oh my goodness!” By this time, Aldana has lost $21 and quits. A fellow sitting on the other side of the van floor is $100 ahead. The baby-talker tells David he looks goofy wearing his blue sweatshirt covered by a girl’s powder blue windbreaker, both with the hoods up. “Everyone has to have a gimmick,” he leers. “The goofier I dress, the more I stand out like a sore thumb.” The other guy is ahead $150 when David gets back in the game with 50 cents to play. He doubles it, then quits

I.. -4~i~ fJ4~ 1I~

again.

Another girl appears on the scene when the blonde disappears for the night. This one, 17 years old and 5-foot-10, is told by Aldana, once he learns where she lives, “You’re geographically undesirable, besides being

too tall.”

Gene Hammond, with $175 more than he started with, leaves with everyone else’s money, including $65 formerly belonging to Willard. The beer is all long gone, and David decides to

split.

Asked if he parties less before Nationals, Aldana speaks about such things: “You can be a doper or an alcoholic, and I’m right there with the alcoholic, I guess. I’d just as soon get drunk, and it’s the least against the law. Party any less before Nationals? No, the same, always. The best I’ve done sometimes, I was so hung over I could hardly walk, just terrible, and I’ve done really good. Maybe I’m still drunk when I’m riding the motorcycle, I don’t know. But I don’t drink to ride them or anything. I’ve tried like not drinking anything for two or three days to really be dried out, but I don’t think it made any difference.” Up the next morning about eight, David tightens his bike’s chain, cleans the points, and checks the plug, meanwhile keeping an eye out for honeys on the loose. “I’d rather meet girls being crazy (hanging out cars and yelling for example) than have them say ‘Oh, you’re David Aldana.’ That way when I quit racing I’ll have something to rely on. When a girl finds out my last name, a lot of times they say ‘Oh my, you’re friends with so-and-so,’ and I think ‘Blown out already.’ I know how

rumors spread and stories get stretched. They think I’m the sex fiend of Santa

Ana.”

Aldana, who hates loud trucks and whose own van is very quiet in spite of dual exhausts exiting on the same side, can see advantages to the AMA requiring mufflers on competition bikes.

“Sometimes when you’re behind someone for long in a 30-lap race, like those miles are, it starts to hurt your ears. The pipes come right up and hit you right in the face, especially when you’re drafting somebody for a long time, every straightaway. Sometimes for a real long road race I put cotton in my ears because if you don’t your ears are going waaah, waaah, waaah afterwards and you can’t hear. In a road race you draft people, but it’s not a constant thing like dirt track is. It’s easier on my ears with mufflers, and I like that part of it. The noise has a little to do with the thunder and excitement for the spectators, but it doesn’t matter to me. I got a muffler they put on my bikes (at Albany) that added half a horsepower

for the mile.” On the line for the start of the desert race later, a couple of riders nearby suspiciously eyed a photographer concentrating on David. One said to the other, “That’s Aldana about four or five guys down—it looks like that’s who it

is.”

David spoke to a friend who was wearing shoulder pads. “If you don’t crash, you don’t need all that stuff.” The banner dropped and, for once, David’s BSA started the first kick in the usual dead engine start, and he was off with the leaders. Waiting in the pits for the riders to come off the first loop of the race, Mike Martin said, “If David makes it in, he’ll

be in the top ten, but you know David—he sure crashes. He doesn’t pay any attention to rocks or anything.” At last the first dust plumes head in from the initial 40-mile loop, turn into far-off dots bouncing across the washes and rocks, enlarge into riders, and hurry toward the waiting pits. Five racers come through in a few moments, strung out, slide in for gas and goggles, and take off again in about the same order they came in. Then a bright blue jersey attached to a thump-thump-thump sound comes down the trail. It’s David Aldana, on his stock-framed BSA 500, running 6th overall among the best Southern California desert specialists! Mark Adent passes him just as he pits for gas, and then David’s out for loop

Five or ten minutes later, Aldana idles into the pits from the opposite direction, parks, and sits down. He tells the gathering that he crashed and hit his head. “I stuck in the ground like a dart. I felt kind of cuckoo and came back.” After sitting around for awhile, he

rides his bike back to his van, hitches a ride with Willard (who finished) over to the crowd milling around the finish area, finds out that Brooks won, and wanders in the masses. A half hour later he’s headed for the nearby van of Mike Martin, walking like he’s hurting. He lies down in the back of Mike’s van, pushing loading ramps and other stuff aside. So conveyed back to his truck, David shows no intention of getting up out of the van, cradling his head, until a compadre tells him to stay there and take it easy, that he will load Aldana’s

van for him.

David is almost immediately walking around. “Did you hear the thunder? One of my mottoes is that when the going gets tough, the tough keep on going. I hate being a baby, so I have to stand around here in agony and make it hurt worse than before.” Suddenly, he turns and asks, “How’s my hair look? Is he still taking pictures?”

Then, dropping six aspirin with a can of creme soda, and having loaded all his equipment and the bikes into his van, Aldana begins the 250-mile drive home, non-stop, leaving behind this thought: “I can win one of these overall, if enough guys break down. Like if Bakken got a bad start and Brooks broke down. . . .” David Aldana doesn’t have time to be sick or hurt. He’s got a legend to catch, gj

his ta (4~4 4 EIé~A~e~,i 14141444~. Se4üd . ,

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontA New Column For Dirt Riders, A Note On the Cycle World Show, And A European-Style Gp In the U.S.?

March 1975 -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1975 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeedback

March 1975 -

Departments

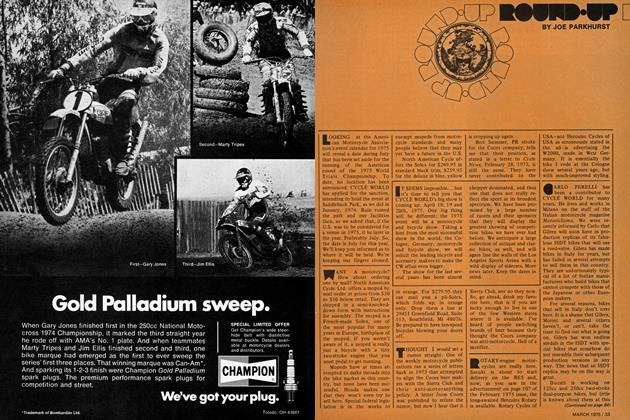

DepartmentsRound Up

March 1975 By Joe Parkhurst -

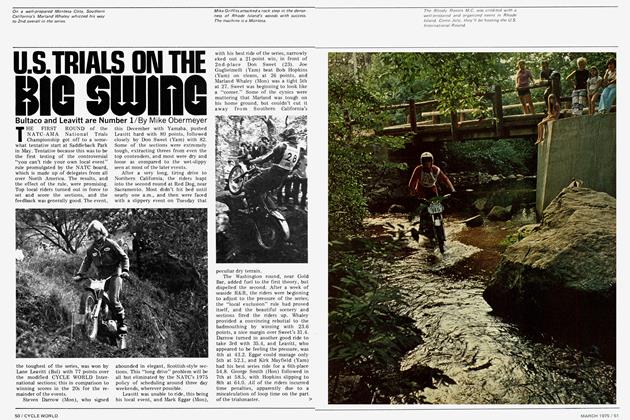

Competition

CompetitionU.S. Trials On the Big Swing

March 1975 By Mike Obermeyer -

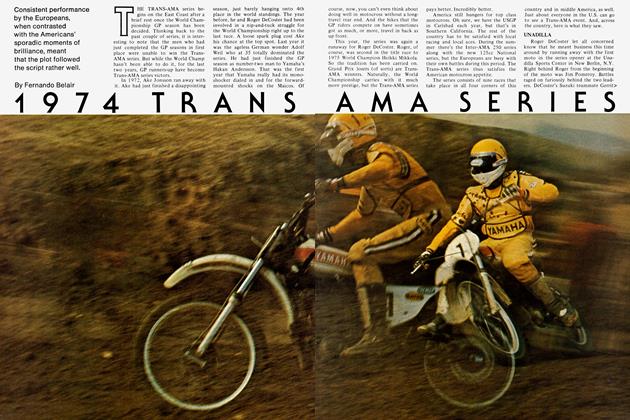

Competition

Competition1974 Trans Ama Series

March 1975 By Fernando Belair