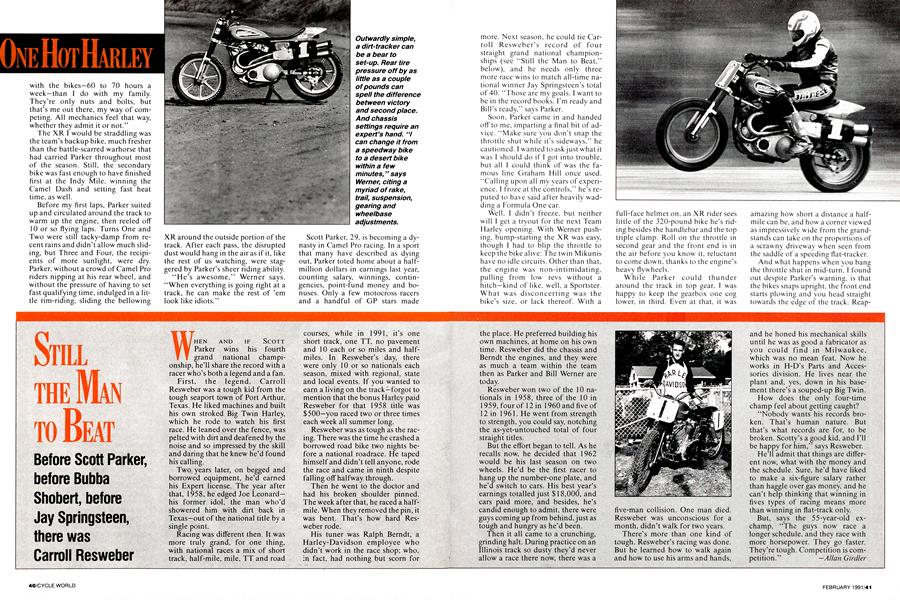

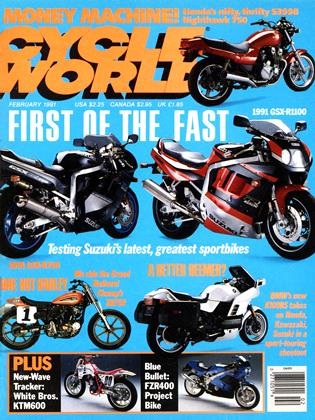

STILL THE MAN TO BEAT

Before Scott Parker, before Bubba Shobert, before Jay Springsteen, there was Carroll Resweber

WHEN AND IF SCOTT Parker wins his fourth grand national championship, he’ll share the record with a racer who’s both a legend and a fan.

First, the legend. Carroll Resweber was a tough kid from the tough seaport town of Port Arthur, Texas. He liked machines and built his own stroked Big Twin Harley, which he rode to watch his first race. He leaned over the fence, was pelted with dirt and deafened by the noise and so impressed by the skill and daring that he knew he’d found his calling.

Two years later, on begged and borrowed equipment, he’d earned his Expert license. The year after that, 1958, he edged Joe Leonardhis former idol, the man who’d showered him with dirt back in Texas-out of the national title by a single point.

Racing was different then. It was more truly grand, for one thing, with national races a mix of short track, half-mile, mile, TT and road

courses, while in 1991, it’s one short track, one TT, no pavement and 10 each or so miles and halfmiles. In Resweber’s day, there were only 10 or so nationals each season, mixed with regional, state and local events. If you wanted to earn a living on the track—forgot to mention that the bonus Harley paid Resweber for that 1958 title was $500—you raced two or three times each week all summer long.

Resweber was as tough as the racing. There was the time he crashed a borrowed road bike two nights before a national roadrace. He taped himself and didn’t tell anyone, rode the race and came in ninth despite falling off halfway through.

Then he went to the doctor and had his broken shoulder pinned. The week after that, he raced a halfmile. When they removed the pin, it was bent. That’s how hard Resweber rode.

His tuner was Ralph Berndt, a Harley-Davidson employee who didn’t work in the race shop; who. in fact, had nothing but scorn for

the place. He preferred building his own machines, at home on his own time. Resweber did the chassis and Berndt the engines, and they were as much a team within the team then as Parker and Bill Werner are today.

Resweber won two of the 10 nationals in 1958, three of the 10 in 1959, four of 12 in 1960 and five of 12 in 1961. He went from strength to strength, you could say, notching the as-yet-untouched total of four straight titles.

But the effort began to tell. As he recalls now, he decided that 1962 would be his last season on two wheels. He’d be the first racer to hang up the number-one plate, and he’d switch to cars. Elis best year’s earnings totalled just $18,000, and cars paid more, and besides, he’s candid enough to admit, there were guys coming up from behind, just as tough and hungry as he’d been.

Then it all came to a crunching, grinding halt. During practice on an Illinois track so dusty they’d never allow a race there now, there was a

five-man collision. One man died. Resweber was unconscious for a month, didn’t walk for two years.

There’s more than one kind of tough. Resweber’s racing was done. But he learned how to walk again and how to use his arms and hands.

and he honed his mechanical skills until he was as good a fabricator as you could find in Milwaukee, which was no mean feat. Now he works in H-D’s Parts and Accessories division. He lives near the plant and, yes, down in his basement there’s a souped-up Big Twin.

How does the only four-time champ feel about getting caught?

“Nobodv wants his records bro-

ken. That’s human nature. But that’s what records are for, to be broken. Scotty’s a good kid, and I’ll be happy for him,” says Resweber.

He’ll admit that things are different now, what with the money and the schedule. Sure, he’d have liked to make a six-figure salary rather than haggle over gas money, and he can’t help thinking that winning in fives types of racing means more than winning in flat-track only.

But, says the 55-year-old exchamp, “The guys now race a longer schedule, and they race with more horsepower. They go faster. They’re tough. Competition is competition.” —Allan Girdler

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontAscot Eulogy

February 1991 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeDoin' the Norton Rap

February 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsLetters From the World

February 1991 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1991 -

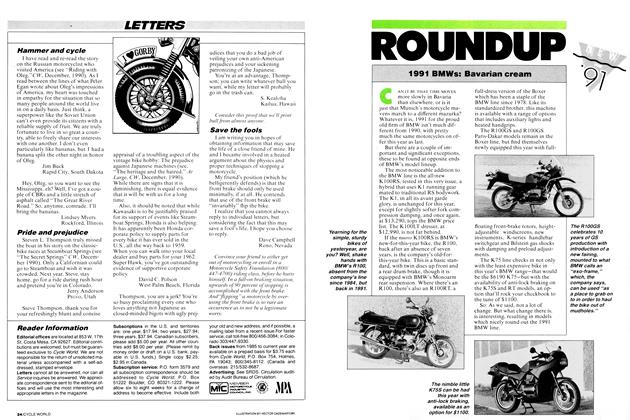

Roundup

Roundup1991 Bmws: Bavarian Cream

February 1991 -

Roundup

RoundupCzeching Out Jawa

February 1991 By Pavel Husák