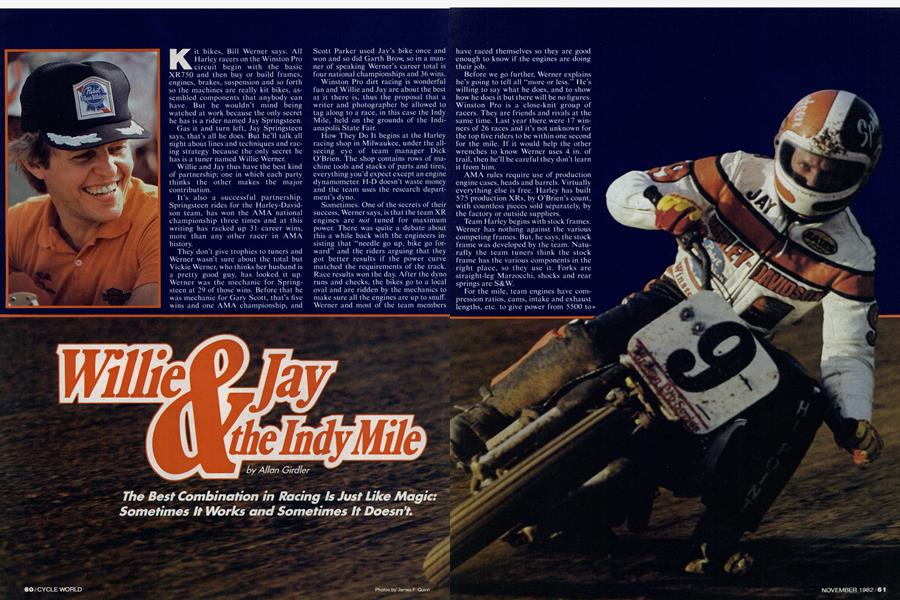

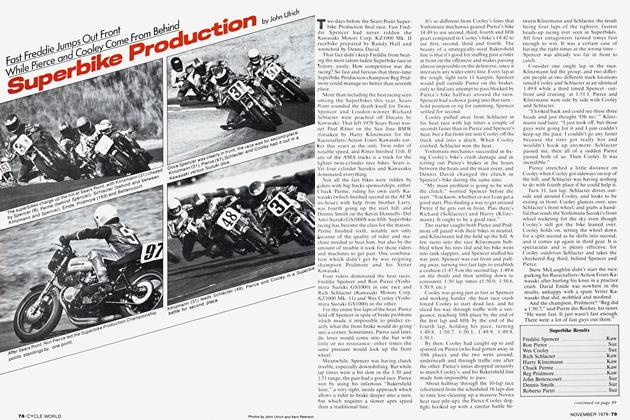

Willie & Jay the Indy Mile

The Best Combination in Racing Is Just Like Magic: Sometimes It Works and Sometimes It Doesn't.

Allan Girdler

Kit bikes, Bill Werner says. All Harley racers on the Winston Pro circuit begin with the basic XR750 and then buy or build frames, engines, brakes, suspension and so forth so the machines are really kit bikes, assembled components that anybody can have. But he wouldn't mind being watched at work because the only secret he has is a rider named Jay Springsteen.

Gas it and turn left, Jay Springsteen says, that’s all he does. But he’ll talk all night about lines and techniques and racing strategy because the only secret he has is a tuner named Willie Werner.

Willie and Jay thus have the best kind of partnership; one in which each party thinks the other makes the major contribution.

It’s also a successful partnership. Springsteen rides for the Harley-Davidson team, has won the AMA national championship three times and at this writing has racked up 3 b career wins, more than any other racer in AMA history.

They don’t give trophies to tuners and Werner wasn’t sure about the total but Vickie Werner, who thinks her husband is a pretty good guy, has looked it up. Werner was the mechanic for Springsteen at 29 of those wins. Before that he was mechanic for Gary Scott, that’s five wins and one AMA championship, and

Scott Parker used Jay’s bike once and won and so did Garth Brow, so in a manner of speaking Werner’s career total is four national championships and 36 wins.

Winston Pro dirt racing is wonderful fun and Willie and Jay are about the best at it there is, thus the proposal that a writer and photographer be allowed to tag along to a race, in this case the Indy Mile, held on the grounds of the Indianapolis State Fair.

How They Do It begins at the Harley racing shop in Milwaukee, under the allseeing eye of team manager Dick O’Brien. The shop contains rows of machine tools and stacks of parts and tires, everything you’d expect except an engine dynamometer. H-D doesn’t waste money and the team uses the research department's dyno.

Sometimes. One of the secrets of their success, Werner says, is that the team XR engines are not tuned for maximum power. There was quite a debate about this a while back with the engineers insisting that “needle go up, bike go forward” and the riders arguing that they got better results if the power curve matched the requirements of the track. Race results won the day. After the dyno runs and checks, the bikes go to a local oval and are ridden by the mechanics to make sure all the engines are up to snuff. Werner and most of the team members have raced themselves so they are good enough to know if the engines are doing their job.

Before we go further, Werner explains he’s going to tell all “more or less.” He’s willing to say what he does, and to show how he does it but there will be no figures. Winston Pro is a close-knit group of racers. They are friends and rivals at the same time. Last year there were 17 winners of 26 races and it’s not unknown for the top five riders to be within one second for the mile. If it would help the other wrenches to know Werner uses 4 in. of trail, then he’ll be careful they don’t learn it from him.

AMA rules require use of production engine eases, heads and barrels. Virtually everything else is free. Harley has built 575 production XRs, by O’Brien's count, with countless pieces sold separately, by the factory or outside suppliers.

Team Harley begins with stock frames. Werner has nothing against the various competing frames. But, he says, the stock frame was developed by the team. Naturally the team tuners think the stock frame has the various components in the right place, so they use it. Forks are straight-leg Marzocchi, shocks and rear springs are S&W.

For the mile, team engines have compression ratios, cams, intake and exhaust lengths, etc. to give power from 5500 to> 9000 rpm, with best results between 6000 and 8700.

O’Brien sets the basic limits and sets them wide enough to let each rider and chief mechanic use their own combinations. Randy Goss, for instance, likes quicker steering than Springsteen does. Goss doesn’t like to move around on the bike and he knows exactly where he wants the grips. Springsteen (and Werner) can’t ride Goss’ XR and the same goes for Goss and his tuner Brent Thompson on Springer’s bike, but no matter, they get to do it their own way.

Dirt track racing isn’t exactly done on dirt, at least not on the kind of dirt under the grass on the lawn. Dirt tracks used for motorcycles, cars and horses have evolved over the decades into a surface of their own, mixes of local dirt, as in red clay here, loam there, plus sand and clay and crushed limestone, treated with chemicals such as calcium and watered in hopes the water and calcium will give just the right blend of hardpack and loose cover. No dust, no mud, no ruts.

The Indy Mile is usually run during the fair, after the cars have packed the surface. This year the first event was before the fair, so Werner expected the track to be rough. It had rained during the week. That meant a chance of water and guesswork on the part of the ground crew; how much calcium would be just right? Werner figured on bumps, a narrow

groove through the turns and enough cushion, the inside word for the loose cover that’s swept off the outside of the groove, to let the better riders go high and outside.

For Indy, Werner prepared Springsteen’s No. 1 bike with lots of steering rake so it will be stable on the straight, and not much trail. This makes the steering light and will reduce kickback on the bumps and ruts, if they develop. The suspension is stiff.

The second bike had the same trail, more rake and softer suspension, dialed in before the truck left the shop.

Gearing changes are done with the rear sprocket. There isn’t any need to juggle gearbox internals because the bikes will be in top all the way. And although the XR has chain primary and gearing can be varied here, Werner doesn’t like to. Change the primary ratio and you also change the torque being fed to the gearbox and thus the rear sprocket and that affects how chain tension feeds loads into the rear suspension, and that . . . you get the idea. No one thing can be changed without affecting something else, so Werner isolates where ever he can.

All the tuners work this way, so as a shorthand they don’t talk about 44 teeth or 16/45 the way the catalogs do, but in terms of “five-thirty-four” as in 5.34:1. Both Springer’s machines were geared five-thirty-four.

All the team engines are using 37mm Mikunis. Mikuni doesn’t make a 37? Right. The carbs were arrived at by checking maximum air flow with the valves and ports that work best, then sleeving down the carbs to flow just as much air as the engine will take at peak. The 37s give equal power and work better in the mid-range.

Werner has devised twin ignition, with two plugs per cylinder. Both fire at the same time, via parallel coils. Werner is not paranoid about ignition, he says, because you aren’t paranoid if they are out to get you and he once had 15 magneto failures in one season. He first devised a double system, with switches to go from one to the other if needed but that too was risky; imagine fumbling for the switches while drifting the dirt at 100 mph. Now each cylinder has two plugs, one on each side of the combustion chamber. There’s no difference on the dyno but the engines do seem to be more tolerant of carburetion quirks and Springsteen hasn’t suffered an ignitionffailure since.

Tires and wheels are a subject all their own. Carlisle and Goodyear provide the racing tires, with a road-legal 19-in. Pirelli used on the front under some conditions. Treads for all are about halfway between a trials universal and a knobby, done by strict rules. There’s a choice of tire width and of rim width. Plus, because the same tire will have a different profile on a different rim, the tuner can vary contact patch size, steering trail and steering behavior by which tire size is used on which rim. Then, the narrow tire will bite better on the cushion, the wide tire will have more contact patch on the groove.

Further, with the bike at the same lean angle, it will turn more sharply with a wide tire because the contact patch moves toward the inside. This gives a quick turn with the wheels in line, as opposed to sliding or drifting.

Goodyear offers hard and soft compounds, in the same size. Carlisle has one rear compound, a medium, in two sizes.

Leafing through his black book— brown, actually. He hates cliches—for Indy Werner has installed Goodyear hard tires on the rear, Carlisle on the front. One bike has wider rims than the other.

Pause for breath here. Werner can tune the engine to have as much power as the tires will transmit, in the rev range that will let the engine last the race with some for insurance. He can alter power delivery with intake tract and exhaust pipe length. He can do the same with gearing. He has alternate mounting locations for the shocks as well as other shocks and springs. He can change the swing arm pivot, wheelbase, rake and trail, and he can change rake without changing trail and vice versa. He can change ride height by changing the suspension, and ride height without changing the suspension. Pick any choice, multiply it by all the other choices and the combinations run into seven figures.

A magazine, okay, this magazine, once remarked on the lack of sophistication in dirt track. Apologies are offered, which Werner cheerfully accepts, adding that that reporter simply didn’t ask the right questions.

We are at the track. The track is very wet. Smooth and gooey. Dogs are leaving footprints. Shoot, birds are leaving footprints. The track crew begins circling with spiked rollers. The sun is beating down and there’s a wind. Loosening the surface will help it dry.

In case it doesn’t, Werner begins carving a tire, bevelling the back of each block to expose more leading edge. As the track packs down, he adds, the blocks will wear off their taper and put more tire

on the ground. One rear tire has a 3-in. rim, the other bike wears a 3.5-in. rim. The narrow rim forces the tire into a peak, again for more bite in a soft surface. Just in case he readies another front wheel with a Pirelli MT53, DOT legal and the best front tire if it’s really wet.

Meanwhile Springsteen has arrived. Finding Werner doing all the worrying, he teases his girl, Debby, about her pit bike being a mini bike for mini people. Debby isn’t massive but she protests, in mock indignation, that the kid’s bike “is a big person’s bike.’’

When her back is turned Springsteen» grabs the thing, picks up Scott Parker and Terry Poovey and rides in triplicate off to see how the track is. They aren’t alone. Early fans are treated to a show, American’s toughest racers doing their imitation of Shriners in a 4th of July parade. They don’t seem to mind.

Springsteen finds a crack in his steel shoe. Werner gets out the portable welding outfit and turns cobbler. What an old piece of iron, somebody says. Springer holds the rusty shoe up by its grundgy strap. Had it seven years, he says, this is my whole career.

Werner bump-starts the No. 1 bike, warms it and changes to colder plugs. Springsteen goes out and runs four hard laps, while the No. 2 bike is readied. He swaps and goes out again, at ease, relaxed and fast out of the crate. Good, says Werner, we’ll be able to read the plugs and know how they’ll be at racing speed.

The pits are total, shattering noise. Fifty big Twins revved at once. Mechanics are riding up and down, self-consciously proud. Forget the paperwork, when tuners talk about their bikes, they mean it.

Goss comes in for his second bike, wheelies away. Mike Kidd and Scott Pearson are out on the odd-sounding Honda NS750s, tuned to run as Twingles, that is, firing both barrels on the same revolution instead of alternating.

Funny thing, that. Werner has built Harley Twingles and Springer has won on them. Honda tuner Jerry Griffith remarked at the time—before the Honda program—that there must be something to it. And Honda’s tests show more power that way. But Werner says there’s more to it than shows. He says he didn’t tell Griffith and he’s not going to tell me. I think of this as a trio of Harleys dusts Kidd on the straight and decide I don’t blame him.

Springer comes in and says he likes the No. 1 bike, the one with less rake, more trail and the harder rear suspension. The track is rough, especially in the first corner and the firmer bike handles the hops better. Also, Jay is riding high going in and close to the poles in the middle of the turns and the No. 2 bike feels loose, doesn’t want to stay in the groove.

“Hot,” says Springsteen and he douses his bandana in the cooler and wipes his face.

More practice. Springer is out running with Ricky Graham, who is on a roll and leading the points race. He’s taking a different line, going into the turns close and running high off the center, a diamond. He’s coming out hard and pulling Springer onto the straights.

Springer reports, and Werner has already seen it. He pulls off the rear wheel.

“Let’s try one thing at a time. You can beat him inside.”

Werner digs a larger sprocket out of the stack, swaps and puts on the wheel. Jay needs more drive coming off the turns so they’ll go to a five-forty-eight. On the other side of the pit a knock-out, a 10, in halter and tiny shorts is bending over an XR. She almost hides a smile and tells Springsteen to pay attention to his work. Unlucky Werner is facing the wrong way, so Springer tells him to pay attention to his work. He does. Almost.

The track is getting faster as it dries. There’s a good cushion and the best line seems to be staying out by the wall, kicking the bike sideways and using the cushion to pull down without shutting off the power. (!) Stay in close coming out and the groove will have traction enough.

Scott Parker is the new kid on the team. He and tuner Al Spengler follow Jay’s lead on the gearing, even though Rick Toldo, who sponsored Scott when the rider began and has joined the Harley team with him, has been listening to Graham’s engine. “It’s geared too high. He can’t run like that all race.”

Time trials have begun. There are 60 entrants. Every one will have a clear shot, and only the best 48 will run in the heats to see who makes the main event, the one with the points and money. The sun is low in the sky and as the air cools humidity rises. So does the calcium in the dirt. Traction improves and the track speeds up.

Willie and Jay have another conference. The tire used for the timed laps is prime, just the right amount of wear to have at the beginning of a race. They swap rear wheels, to use a fresh tire for the heat and have a sure tire for the main.

Family time. Surely no other form of racing is like Winston Pro. Toldo helps Werner round up some washers. Goss comes looking for a brake line fitting. Try the blue box, says Willie without looking up and sure, the fitting is in the blue box. Some local guys lug a set of pipes into the team’s space. The pipes are so tired they’re cracking. Can they use the welding torch? No problem. Springsteen gets the torch and pitches in. The announcer gives the times. Gary Scott is fastest, then Springer, Graham, Parker and Goss. Springer seems more interested in the welding than the times.

Not so with O’Brien or Charley Thompson, H-D president. Thompson had a heart attack several weeks earlier. He’s supposed to be home in bed. But he called the doctor in Milwaukee and said seeing as he’s got an appointment anyway, any objection to him taking a slight detour, say to Indianapolis? Have you quit smoking? asks the doctor. Yes, Okay.

Thompson seems to think the trade is worth it.

He and O’Brien like the times because the races are run under fairgrounds rules. The top three riders in each heat make the main event, and the fastest man in the time trials gets his choice of starting position in the first heat, the second man ditto in the second heat, etc. The times put Springsteen, Parker and Goss in the front row in separate heats. They’ll race each other when the time comes but it’s better if that time is the main.

Werner has been reading the air density meter he carries with him. The air is thicker so to be safe he increases main jet size by one step. Then he drapes a cover on the bike. If the engine cools, they’ll have to go through the cold-start drill again and he’d rather not.

The first heat is flagged away. Scott leads five laps, five fast laps, but Goss gets past and wins. In the second heat Jay charges off the outside and wins going away, trailed by Alex Jorgensen and Scott Pearson on the Honda. Graham takes the third heat, no surprise.

The fourth heat, surprise. Scott Parker is second, behind Bubba Shobert. Nobody expected this. Shobert is a contradiction in terms, a quiet Texan. He had a great record as a novice but while some riders, Springsteen and Ken Roberts for instance, rose to the top their first season with the big guys, Shobert was more normal in that he’s been working up slowly. He’s a good man, one of the few riders who’ll take the time to explain what’s happening. He was fast qualifier at the Ascot half mile this year but that was on a borrowed bike, speaking of family and anyway, the Winston riders feel, Shobert lacks confidence. (That may come, as we’ll see.)

Springsteen and Werner aren’t paying much attention to the heats. “Are you going to change anything, Jay?” “What for?” “Oh, I dunno, maybe you’d like to lap the field.”

Werner snorts at the exchange. He’s busy putting on the prime tire and he’s busy thinking. The track has stabilized. Lap times in the first heat were in the 36s, that is, 36 sec. They slowed to low 37s, then high 37s and stayed there.

Willie is debating himself. If the track gets fast, and Jay runs wide open, perhaps another step richer on the jets will be good insurance. While he mulls that, he swaps for a new battery, just in case. Then he checks the tire pressures and covers the bike again, while the photogapher marvels “The man never quits.”

There are debates like this going all over the infield. This family is like a real family, as contrasted with one big happy family. There are inner circles and people who really don’t like each other much, never mind all the shared good times and bad. There are tuners who like each other but not each other’s crews, and there are riders who are presumed to be trying to lead rivals astray.

Werner doesn’t take part in this. He’s reading the track. He changes the front wheel for one with a wider rim, for the

larger contact patch. He decides to stick with the jets used in the heat race. He’s really worried about the rear tire. If it’s too hard, Jay can’t get the power down. Too soft and it’ll overheat. He compromises, by keeping the hard tire and cutting the knobs lengthwise so they’ll flex and warm up quicker.

Elsewhere the other guys are watching each other. Why did Gary Scott turn five fast laps and slow down? Why did he cover his front tire? Why did Steve Morehead wax the other riders in the second semi? What tires does he have on? What gears did Tex Peel put on Graham’s bike and can it go the distance turning that fast?

Tex Peel is on a roll of his own. He’s wearing a cast on his left foot and he laughs when reminded “Riders limp. Tuners don’t limp.”

“It’s all Ricky’s fault. When he fell at Knoxville I jumped off the wall.” (If Peel doesn’t weigh 300 lb. he’s doing his best to look like it.) “I broke a bone in my foot.”

This is Peel’s best season. They lost a gearbox and got points. Graham fell and they still collected points. For the record, Graham’s XR has a medium compound Carlisle on the rear, a soft Carlisle on the front and it’s geared five-fifty-five.

Back in the Team Harley camp, Spengler is checking valve clearances.> Parker’s bike isn’t coming out of the corners hard enough and they don’t know why. They’ll run the soft rear tire.

Speaking of family, Jay is sorry to learn his own XR isn’t in the main event. Yes, his own. Along with the three bikes provided by the factory, Springsteen owns an iron barrel XR750 he uses for ice racing and an alloy XR. He’s a sponsor, with his dad helping on the crew of his younger brother Chuck. But Chuck missed the cut.

(At the Sacramento mile, Chuck made the main event and Springsteen looked happier about that than about his own win. Well, commented Werner, Jay’s won more nationals than Chuck’s been in.)

The riders line up for the main event and the rest of the team casually strolls out of the pits and over to the giant H-D team truck. All day and night the security guys have been telling people to

get down from there but we figure they’re fans too and when the race is on, they won’t be looking anywhere except the track. We’re right.

The race is onOh my God. Springer comes off the front row like a rocket, pitches for the turn and the bike spins out. It’s completely horizontal and somehow comes back onto its wheels but the pack is headed for the second turn.

To hear him tell it later, Jay wasn’t excited. He rode it out sideways and realized “I’ll be able to save this thing” so he wrestled the rubber side back down and set off.

Four guys are in front, back and forth, in and out. It’s Graham, Goss, Shobert and Morehead swapping positions two and three times each turn. Springer works his way forward. He and Parker battle each other and they can’t close up on the leading quartet. Graham powers

into a slight lead and comes past in front.

Halfway through the second turn, the tiny lead figure slows, we can see it from way back here and the trio drives away. Graham comes down the start-finish straight trailing smoke and running on one cylinder.

Goss and Shobert trade the lead as the white flag comes out, last lap. Shobert leads down the back stretch, Goss goes high and around into turn three, Shobert tucks down on the groove as they exit and he’s got the drive, enough to be half a bike ahead at the flag. It’s his first national win and in victory circle, he’s as cheerful as you’d expect, saying he’s known he’d win a national one day and it’s about time, too.

But many in the crowd missed the finish. On the next-to-last lap Springsteen changed his tactics and drove down off the wall into the first turn, hoping to power past Terry Poovey for fourth place. Poovey didn’t expect Springer there and came in too fast, so he braked. Springer rammed him and highsided. Hard. He got to his feet and he and the bike were hauled to the pits. Poovey recovered from the bump and took fourth.

Post-mortems were surprisingly brief. Toldo was right, and Graham’s engine didn’t go the distance, while Tex was also right and Graham one-lunged to the flag in seventh, in the points again. Scott didn’t have a secret; he was sixth, and Morehead got third so maybe his combination was the right one. Parker’s soft tire worked for 10 laps and went all blubbery. Goss was so close there was no point in even thinking about it.

Willie and Jay were circumstantial. The engine ran fine but the hard rear tire was just that fraction wrong. The track didn’t develop the grip Willie expected, so even if it hadn’t been for the first lap spin and the . . . the words are wasted.

But while we’re on the subject of hindsight, the discerning reader may wonder about Shobert’s choice of tire and gears. They aren’t mentioned because the writer didn’t think to ask.

And there’s no picture of Springsteen’s crash because the photographer was walking from turn one to victory circle at the time and the crash took place literally behind his back.

You can’t think of everything. As the team loaded bikes and tires and gear and tools, we all took comfort from the wisdom of Willie Werner:

“I’ve been at this too long to let it bother me. No matter how bad it is tonight, next week’s another week.”

LATE NEWS FLASH

Jay Springsteen won the year’s second Indy Mile, going away. Let the record show that Jay has 32 wins, Willie has 37 and the ace reporters went to the wrong race. Q

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

November 1982 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1982 -

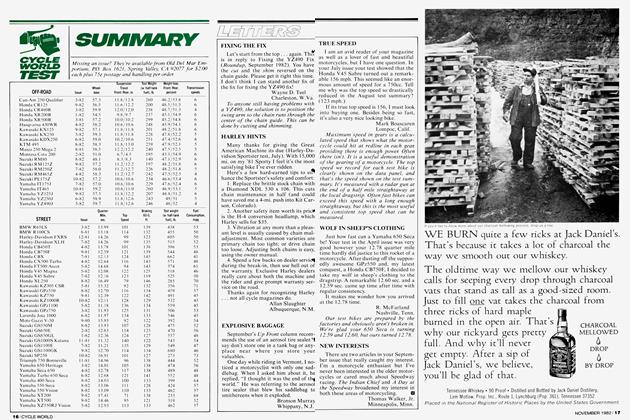

Cycle World Test

Cycle World TestSummary

November 1982 -

Cycle World Roundup

Cycle World RoundupAutomatically Faster

November 1982 -

Ten Best Bikes of 1982

Ten Best Bikes of 1982Even When They're All Good, Some Are Better.

November 1982 -

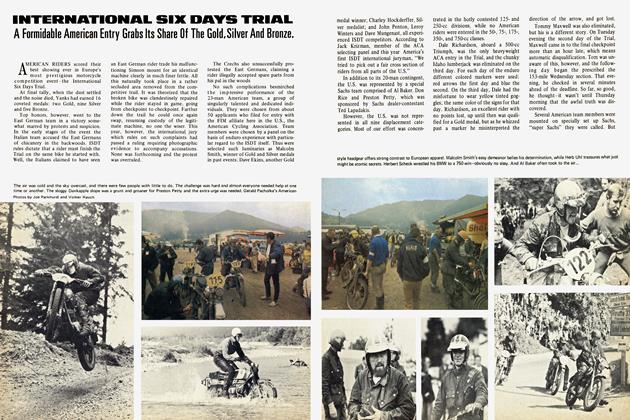

Competition

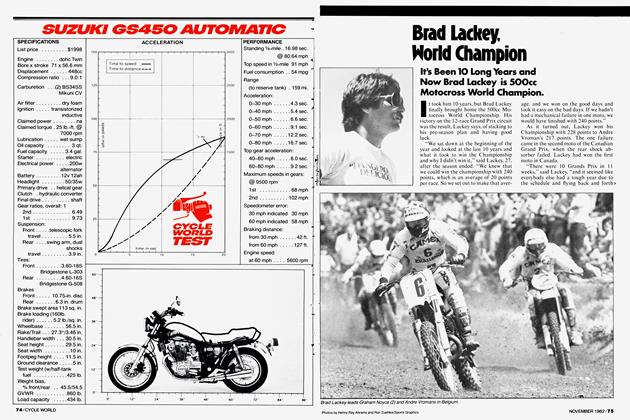

CompetitionBrad Lackey, World Champion

November 1982