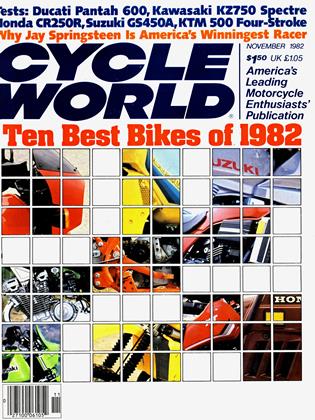

EVEN WHEN THEY’RE ALL GOOD, SOME ARE BETTER.

TEN BEST BIKES OF 1982

While on a trip this past summer one of the crew was challenged by a man who was convinced this magazine has no sense of value. Month after month, he said, Cycle World says nice things about terrible motorcycles.

What do you ride? our man asked. A 1000cc Four, he said. What's it like? Oh, the owner said, it runs like a rocket, handles as if on rails, always starts, never breaks, etc.

Should the magazine have called it a pile of trash?

Of course not! It’s a wonderful bike! Well then, if we say good things about bikes that you know are good, how can you be so sure the other bikes about which we rave are not as good as we say?

Because mine is better than the others. With that the angry man stomped away, still mad.

Welcome to the Seventh Annual Ten Best Bike Awards.

The above anecdote is presented to illustrate several problems that come with the awards territory.

First, we bike nuts all think our bikes are best. If we didn’t, we wouldn’t have them. It follows that anybody who says some other machine is good, or perhaps better, is a fool or a liar or both.

Next, by its nature awards involve classes, just as in racing there’s the 125 class and the 250, with novices against novices, experts against experts and oldtimers vs old-timers.

For reasons of speed and convenience our awards are limited to ten, meaning

we had to draw up ten classes and then assign each eligible model to one class.

Fine, except that motorcycle nuts defy classification. If we conformed to the norm, we wouldn’t ride at all. So sure as bedamned, declaring the Harley FLT a touring bike means somewhere there’s somebody racing one in showroom stock, and someplace else a man with a million miles in the saddle is crossing the continent on the 250 Single declared perfect for city use by newcomers to the sport.

But never mind. The rules create the exceptions, so we’ve simply set down arbitrary procedures and followed them as best we can.

The rules: We will only consider motorcycles in current production and sold in the U.S. Each eligible model must have been tested, not necessarily during the current model year but in the same form as it’s on sale during the year.

Voting is on the basis of merit, that is, how well does the motorcycle do its assigned job? Personal preference is held to a minimum. Just because one juror might prefer to tour on a 350 Twin doesn’t mean that 350 Twin is the best touring bike on the market. Instead the evaluation is on the basis of carrying capacity, seat comfort, passing and pulling power, cruising range, the things considered by those who buy bikes for serious traveling. Superbikes must be fast, enduro models should have a chance of a trophy as good as the rider, motocross machines ought to be able to win, and so forth. Price? Yes, some of the time at least. We are looking for the best in class

and the extras in life do cost money. But if two entrants are nearly equal and one sells for lots less than the other, value will take the day.

The judging is done entirely by the editorial staff, the guys who ride the bikes and write the tests all year. No outside help allowed, excepting our motocross kids. They don’t cast votes but because they can tell us things we can’t learn firsthand, their opinions are listened to.

Why make awards? Mostly because the monthly tests are or are supposed to be concerned only with the motorcycle under review. We like bikes. We enjoy and appreciate bikes. When a new model arrives we think the machine, the makers and the bike nut public are entitled to have tests that involve only the bike itself. Comparisons muddy the water. The important thing is how much does it weigh? How fast does it go? What’s it like after a day in the saddle? The facts and opinions should deal only with the motorcycle, as itself. Group tests and long-range tests provide some basis for preference but we can’t do all the models this way every year.

And after all this blather the fact of the matter is, we like bikes. Some we like better than others. Some get boring and some don’t, some go home the day after the test is finished and some get bought and kept, and seeing as how we have to be fair all year long and riding motorcycles has nothing to do with common sense anyway. . . .

Presenting the Class of'82.

SUPERBIKE: SUZUKI GS1000S KATANA

With the Katana, Suzuki went out on a limb. First impressions are based on looks and the reactions cleave instantly into two schools, love it or hate it. This wasn't exactly an accident. Suzuki has been famous for not giving offense and not making much of an impression at the same time. The GS line of four-stroke street bikes has a wonderful record for speed and reliability while they haven't sold as well as they've performed.

To change that Suzuki called in a consultant designer who came up with a look never before seen on a motorcycle. The factory’s studio worked on the theme while preparing less radical versions of what has become the distinct and successful Suzuki look.

The engine was also a gamble. The intention was to race the Katana, so it got what amounts to a sleeved-down GS1100 engine; the four-valve head and all the performance equipment except that the displacement is 998 cc. Just right for AMA Superbike racing but 10 percent less than the street-legal competition. Displacement means power so the Katana gives away a handful of bhp and fractions of a second to the class rivals. And the suspension is simply too stiff.

So the Katana isn’t perfect. Instead it’s wonderful fun. The Katana is specialized. It looks like what it is, a bike to be ridden and ridden hard.

OPEN MOTOCROSS: KTM 495MX

Open class motocrossers are expected to do more than their smaller peers. First, they must be race-ready, equipped to compete on the track. Beyond that, the open class bike is the play bike for the tough guys, riders with experience and money who want the most powerful, fastest, best handling dirt bike in the whole world and never mind if it's got lights or not.

This isn’t as obvious as it sounds. The big factories can afford not to notice, or perhaps it’s that they can afford to offer motocrossers that only work on motocross tracks, and enduro models with big engines, and playbikes with slog-forever four-strokes, or even to drop the open class MXer if potential sales don’t seem large enough.

What this has done is create an opportunity, into which KTM has moved. Starting point is the 495 engine. It’s got a monstrous (92.25mm) bore, a giant eight-petal reed valve, a huge 40mm Bing carb, dual ignition so the flames can travel across that vast piston crown, flywheels that would do justice to a tractor . .. and more power than any other Single made. There’s a five-speed transmission. The rear shock is American made for American conditions and the forks come with a kit to tune them for the U.S.

The 495 will win motocross, win enduro, win in the desert and out-run anything that wears knobby tires. If you’ve got the money and the skill, this is the best big dirt bike to have.

TOURING: HONDA GL1100 INTERSTATE

Touring has always defied definition: when we began the balloting for this class we had votes for Harley’s new FXRS and Suzuki’s GS1100E, on the grounds that those were machines their fans would prefer to take on long rides. And they’ll do the job, except that Harley and Suzuki offer the FLT and GS1100GK, fairings and bags and all, because the factories know going on trips isn’t all touring is supposed to be.

Honda worked this out first, in 1975. The result was the Gold Wing, shaft drive, water cooling, a boxer Four, a whole list of different ideas. Mile after mile, week after week the Gold Wing ran and ran, in quiet comfort and reliability.

Honda topped the original with the Interstate, factory equipped with full fairing and bags that suited the bike.

The Interstate is still the best package. Honda’s own Aspencade is a set of extras added to the standard extras, but while sound systems and special paint and compressor for the air suspension are nice, they aren’t required. And while the other models with fairings and luggage designed for the bike are good, they still aren’t quite as good.

Touring bikes are for going where you want, with everything you need, as fast as you can get away with. When you get there, you should be as eager for the ride back.

When it comes to all that, the Interstate fills the bill best.

DUAL PURPOSE: YAMAHA XT550

Forget the honorable history of dual-purpose motorcycles for a moment. Yes, the Yamaha DT-1 helped introduce the world to dirt bikes, Honda’s semi-street Twin won the Baja 1000 and so forth. Probably millions of people have ridden billions of happy miles astride go-anywhere 100s and 175s and 250s and 350s.

Despite all that, the hardcore rider never has quite taken to going anywhere and most of them looked the other way because the dual-purpose bike didn’t have power. Then came the 500s; great booming fistfuls of power but they weigh a lot and somehow the power was usually in the wrong place and couldn’t be used.

Comes now the Yamaha XT550 and the complaints vanish. The 550 isn’t perfect, in the sense that it’s still heavy and can’t run with the big two-strokes on rough ground.

But Yamaha did more than anybody else has done to date. The XT550 is easily the most powerful in its class. The forks are big and the single rear shock keeps the bike straight on jumps, so the handling is equal to the other 500 fourstrokes.

The best part is the oddest part: compound carburetors. One carb works all the time, the second comes in on demand. The result is mild power at low revs, perfect control when the rider needs control most.

While having all that wonderful power.

651-800CC STREET: HONDA V45 SABRE

Honda’s engineering is equalled by Honda’s willingness to do things differently, but the 750cc V-Four was still a big surprise. Not for 40 years has anybody made a V-Four and those early examples were more different than they were good.

The Honda engine is both. It’s more compact than the cross-frame Fours, and even with water cooling and shaft drive the V45 weighs less than the equivalent CB750s. The engine was built for high output, then tuned (for 1982 at least) more for reliability and long life than for peak power. Thus the Sabre and its cruiser stablemate, the V-45 Magna, don’t set performance records.

Instead, the Sabre delivers effortless performance, with a smooth delivery that beggars the vocabulary. This is the first Honda in memory that hasn’t been geared to spin too fast on the road. The delightful engine is aided by a shaft drive that doesn’t act like shaft drive, and by suspension that can be tuned for comfort or for crisp handling.

We weren’t too happy with all the electronic accessories; traditionalists on the panel argued that the best in this class should be a composite of the four Kawasaki Fours. And we wish the radiator wasn’t quite so toasty on warm days.

Nothing’s perfect. What the Sabre does is work right, look good and never forget it’s a motorcycle.

250CC MOTOCROSS: SUZUKI RM250

Suzuki doesn’t rest on past success. In 1981 we mentioned that although the 1980 RM250 was great, the ’81 with Full Floater single rear shock was even better.

So for 1982, they’ve done it again. The engine gained water cooling, except that gained isn’t the right word because the engine itself is new, right down to different bore and stroke. The cooling system is fairly simple as these things go, Suzuki now uses a Mikuni carb with rectangular slide, the stanchion tubes have thicker walls, the RMs (and the PE, DR and SP models as well) finally get folding shift lever tips. Equipment that didn’t need any help, for example the aluminum swing arm and the strong hubs with straight-pull hubs, were continued unchanged. And then the engineers added lightness.

The result is the lightest 250 motocrosser, fully 17 lb. less than the Yamaha YZ. The engine is at least as powerful as the competition, while the suspension, front and rear, is still the best made.

Our motocross testing includes a lot of racing. Our riders, well, the best one at least, is good. As a rule he tunes the bike into racing condition, with different tires, adjustments to the suspension, etc.

With the RM250, though, he didn’t touch a thing. Not one. And in one moto he beat a factory bike ridden by Brad Lackey.

451-650CC STREET: KAWASAKI GPZ550

Because this category includes the model year’s high-tech entries, the record should show that there was one vote cast for a turbo, the Yamaha version. Just because a motorcycle contains something new and/or something trendy, doesn’t make it the best or even great, and for model year 1982 turbocharging was news, a statement of engineering skill and expertise, but didn’t live up to the promises made.

The sports bikes, though, delivered. With some exceptions function is formed by displacement; the big new bikes are touring models, the small new bikes are for practicality, so it follows that the middleweights are for riding around and saving money and having fun.

First, it’s fast. In the Kawasaki tradition the GPz is muscular, compact and bulletproof. Lots of punch at midrange, no need to buzz the engine for power. The single shock rear suspension stretches the wheelbase but the suspension itself works well and revising the steering kept the GPz’s ability to flick through turns while the extra length slowed down the steering and makes the bike stable at speed. As a bonus, the GPz looks like a race-derived machine, which fits what it does.

This is a tough class; piles of letters from angry owners of rivals to the GPz attest to that. But the other models fell short in comfort, or engine, or something while the GPz did everything well.

125CC MOTOCROSS: SUZUKI RM125

No prizes for guessing this one. The 125 motocross class is fiercely competitive, at the design level as much as on the tracks. Because this is so, two months ago we rounded up the 125s from the Big Four and compared them. The RM won there, so it wins here.

To recap some, what we found first was that all the bikes are alike in specification, that is, for 1982 they all have water cooling, solo rear shocks, nearly or slightly more than 12 in. of wheel travel.

We had drag races, proving that the pro riders could win the dash to the first turn. The crew practiced and tuned suspensions.

Then we raced the entrants. We used two tracks, one smooth and fast the other rough and tough, to equalize that factor. And we used five riders; one pro, two intermediates and two novices. The 125 is, after all, a beginning for many racers.

We didn’t compare lap times. We used to, but all that proved was that the pros are faster than the others, and that they can win on whatever they’re on and go even faster if it’s the model they race in their other lives.

Instead, we took a vote. After two days on two tracks swapping around on four bikes, the five riders picked their favorite.

The ballots read Suzuki, Suzuki, Suzuki, Suzuki, Suzuki.

UNDER 450cc STREET: YAMAHA XS400

Character is an odd thing to mention in a review of small street bikes. There have been some exotic and expensive machines offered in this category over the years but in the main they’ve been more interesting than popular and remarks about character are usually held in reserve for reporters who like bikes they can’t justify on the grounds of speed or utility or value for the buyer’s dollar.

But what sets Yamaha’s new 400 Twin apart from the others is character.

That’s not the whole story, of course. For several years Yamaha lagged behind the other factories when it came to four-stroke Twins. While Honda had the 400 Hawks, Kawasaki appeared with a strong engine and belt final drive, Suzuki introduced the rangy GS400 and 450, Yamaha persevered with the RD series and had the rough-if-ready four-stroke in the back of the showroom.

This year the vacancy was filled. The new XS400, in Seca mode, looks like the bigger sports models while not offending the way some of the larger Yamahas do. The Seca 400 has the latest design in frames with engine suspended and stressed. The new engine has counterbalancers and it’s smooth. The Seca 400 comes with disc brakes, cast wheels, six-speed transmission, all the good stuff.

What the Seca 400 is, is fun.

ENDURO: KAWASAKI KDX250

Enduro is a big, wide, wonderful world. Too big, really, because while superbikes and motocross classes fall neatly into timed runs and displacements, enduro in effect has come to represent any and every off-road bike that doesn't compete in motocross.

Thus the arguments followed balloting in which votes were cast for four-stroke Singles; reliable, easy to maintain and they offer performance the ISDT riders of 10 years ago could only dream of. The razor-edge timed racers, as in IT465, the latest Husqvarnas and incredible KTMs, are better than motocrossers could imagine back then.

So we threw out all the ballots. Working broadly, considering price and adaptability and value and the ability to do its assigned job better than the others, what’s best?

Kawasaki’s KDX250.

The KDX offers value. The Uni-Trak single shocks offers handling, the forks work for a wide range of weights and rider skills. The engine has competitive power and at the same time will idle and slog around the campgrounds in novice hands. We ran ours in enduros and did well, we flogged it for weekend after weekend and didn’t break it.

The KDX isn’t the fastest, the lightest, the most refined, or the cheapest and smallest. Instead, the KDX250 is the best value.

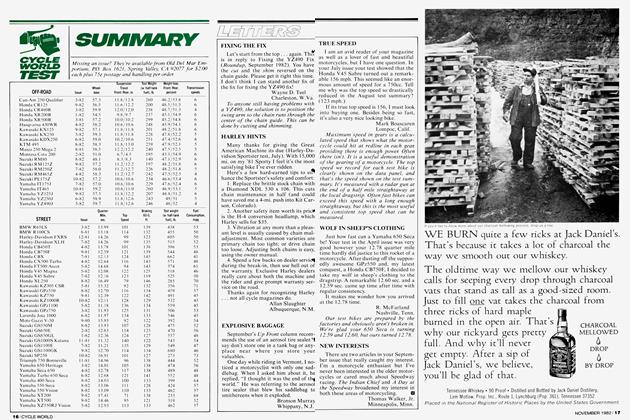

View Full Issue

View Full Issue