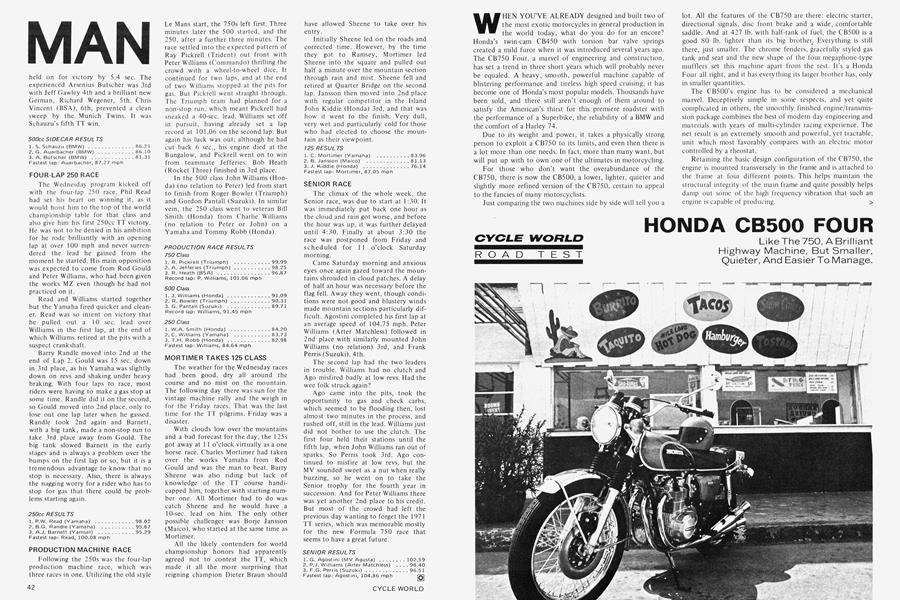

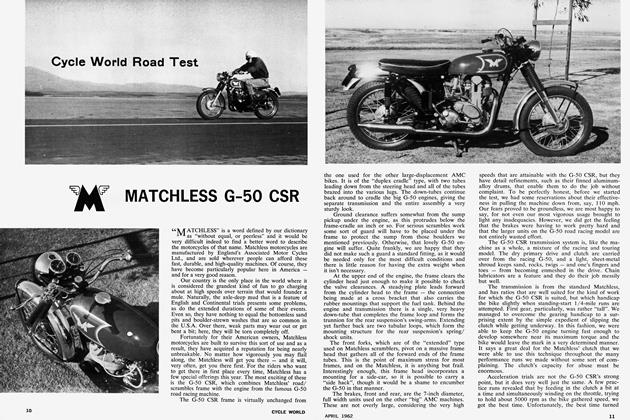

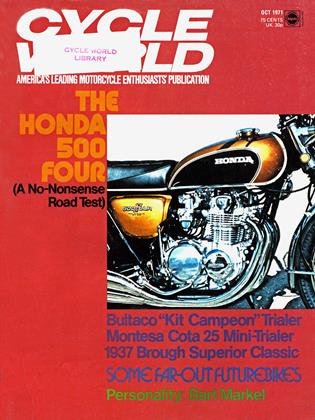

HONDA CB500 FOUR

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

Like The 750, A Brilliant Highway Machine, But Smaller, Quieter, And Easier To Manage.

WHEN YOU'VE ALREADY designed and built two of the most exotic motorcycles in general production in the world today, what do you do for an encore? Honda's twin-cam CB450 with torsion bar valve springs created a mild furor when it was introduced several years ago. The CB750 Four, a marvel of engineering and construction, has set a trend in three short years which will probably never be equaled. A heavy, smooth, powerful machine capable of blistering performance and tireless high speed cruising, it has become one of Honda's most popular models. Thousands have been sold, and there still aren't enough of them around to satisfy the American's thirst for this premiere roadster with the performance of a Superbike, the reliability of a BMW and the comfort of a Harley 74.

Due to its weight and power, it takes a physically strong person to exploit a CB750 to its limits, and even then there is a lot more than one needs. In fact, more than many want, but will put up with to own one of the ultimates in motorcycling.

For those who don’t want the overabundance of the CB750, there is now the CB500, a lower, lighter, quieter and slightly more refined version of the CB750, certain to appeal to the fancies of many motorcyclists.

Just comparing the two machines side by side will tell you a lot. All the features of the CB750 are there: electric starter, directional signals, disc front brake and a wide, comfortable saddle. And at 427 lb. with half-tank of fuel, the CB500 is a good 80 lb. lighter than its big brother. Everything is still there, just smaller. The chrome fenders, gracefully styled gas tank and seat and the new shape of the four megaphone-type mufflers set this machine apart from the rest. It's a Honda Four all right, and it has everything its larger brother has, only in smaller quantities.

The CB500’s engine has to he considered a mechanical marvel. Deceptively simple in some respects, and yet quite complicated in others, the smoothly finished engine/transmission package combines the best of modern day engineering and materials with years of multi-cylinder racing experience. The net result is an extremely smooth and powerful, yet tractable, unit which most favorably compares with an electric motor controlled by a rheostat.

Retaining the basic design configuration of the CB750, the engine is mounted transversely in the frame and is attached to the frame at four different points. This helps maintain the structural integrity of the main frame and quite possibly helps damp out some of the high frequency vibration that such an engine is capable of producing. >

Four exhaust pipes, four carburetors—complicated, to be sure, but aesthetically pleasing and mechanically functional. The four 22-mm Keihin carburetors are similar to the 28-mm units employed on the CB750 and, to a lesser extent, to the constant velocity units on the CB350 Twin. Throttle opening and closure is now accomplished using a “walking beam” arrangement mounted at the center of a cross shaft above and ahead of the carburetor bodies. A result of Honda’s many years of racing, this unit provides positive opening and closing of the throttle slides by the push/pull action of the continuous cable. A rather too strong throttle return spring located between the center two carburetors on the rear half of the “walking beam” required considerable squeezing to hold the throttles open at high speed.

Problems with premature carburetor maladjustment as often experienced with the four separate cables on the CB750 will be a thing of the past with this setup. The carburetors are attached to the cast aluminum intake manifolds by short pieces of neoprene hose, and are supported at the rear (intake side) by a rubber attachment to the air cleaner which serves as a plenum chamber. Therefore, the carburetors move only enough to keep fuel in the float bowls from frothing. Also they are not apt to move in disharmony with each other, causing one or two slides to open before the others. Honda says that throttle synchronization should not normally be required unless the units themselves have been dismantled, and then they should be adjusted only by an authorized dealer.

The camshaft, with asymmetrically shaped lobes, is supported directly in the aluminum of the cylinder head casting and is driven by a single-row chain between the center two cylinders, as in the CB750. However, to guide the chain on its downward travel, a cam chain guide plate is used instead of the roller assembly of the CB750. Being cushioned in a rubber-like cradle on both sides undoubtedly aids in keeping engine noise down.

Oddly enough, there are no springs between the rocker arms and the edges of the tappet cover. The play between these items is considerable when the engine is cold, and undoubtedly increases when the aluminum cover expands from heat. Silent as the CB500 runs, there is an occasional “click” from the camshaft area, which most likely comes from the rocker arms rattling back and forth on their shafts. Iheretore, it seems logical that Honda would have installed Hat springs to take up the clearance, or at least provided Teflon spacers for the rocker arms to bump against.

Moderately sized valves are located in relatively shallow combustion chambers which allow a high compression ratio with the use of flat top pistons. Honda engineers have found that, with such a combustion chamber configuration, more efficient burning of the fuel/air mixture is possible, and exhaust emissions are reduced.

Valve closure is by double coil springs which allow extremely high rpm without valve float. Tappet adjustment is very close (0.0019 in. for the inlet and 0.0031 in. for the exhaust), which also lessens valve gear noise.

Like theCB750,a five-main-bearing crankshaft is employed with the outer two throws opposed to the inner two throws by 180 degrees. Plain main and rod bearings are used, and the heat generated by the bearings is carried away by the 60-lb. oil pressure flow. 1 he left end of the crankshaft supports the alternator rotor, and the twin ignition contact breaker units are mounted on the right end. A spring-type automatic ignition advance unit is used, and is very simple and reliable in operation.

The most interesting new feature on the CB500 is the method of getting the power from the crankshaft to the transmission shaft. A Morse “Hy-Vol” chain, which is almost exactly the same as the chain used on the Oldsmobile Tornado and Cadillac El Dorado automobiles from the engine to the transmission, is featured. The tiny, rectangularly shaped teeth are stacked tightly beside each other and provide almost silent running with high load-carrying capabilities. The same sort of chain is also used on automobile engines to drive the camshaft from the crankshaft. Over 99 percent efficiency is claimed for this chain, along with improved wear and reduced noise characteristics.

Rubber shock absorbing bumpers are mounted in the rear Hy-Vol chain sprocket to cushion the engine’s power impulses and the effects of vigorous shifting before they reach the transmission. Both ends of the clutch shaft are supported in enormous ball bearings.

Like the transmission on the twin-cylinder CB450, the shafts are set one behind the other. A drum-type shifting mechanism is completely encircled by three shifter forks, and is mounted on ball bearings. Our test machine shifted like a dream when cold, but as engine temperatures rose, so did shifting effort. A determined prod was necessary to downshift to pass traffic, and the lever would occasionally stick down or up, depending on which way you had just shifted, necessitating some fast toe work to return it to the neutral position before another shift could be made. We trust that Honda will work out this annoying Haw in an otherwise superb transmission before more of these machines are set loose on the public.

In the interests of ease of service and oil tightness, Honda has once again employed a horizontally split crankcase assembly. An unusual feature is the externally mounted trochoid oil pump which nestles just in front of the countershaft sprocket on the left side of the machine. It is gear driven from the primary shaft and is kept fed with oil from a pickup located in the bottom of the crankcase. Oil from the pickup’s strainer is directed to the tinned full-flow filter unit at the front of the crankcase and then to the crankshaft. A takeoff further directs the oil upward to the camshaft mechanism. Oil from the numbers one and four crank areas is force fed to the transmission and primary drive. The engine’s 6.4-pt. oil supply is carried in the crankcase instead of a separate oil tank like the CB750, which means more rapid cooling of the oil supply and no chance of oil loss from a ruptured oil line.

Despite the fact that the entire oil supply is carried in the sump, the engine’s overall height has been kept quite low. Part of this is due to the “oversquare” bore/stroke dimensions. A top end overhaul can be performed on the CB500 without removing the engine from the frame. Another bonus from the engine’s lowness is a lower center of gravity, which greatly nhances low speed maneuverability and stability.

Final drive is again by chain, but this chain will probably be a lot more trouble free than the CB750’s rear chain, which was a big headache for some owners. The chain just wasn’t strong enough to handle the 750’s enormous torque. The CB500 is equipped with a chain which is the same size as the C'B750’s and should be very reliable. Rubber blocks are again incorporated between the rear sprocket and the rear wheel to make life as easy for the chain as possible.

The new smaller diameter (10.24 in.) front brake disc still provides the best stopping power in the motorcycle industry and has added the bonus of more lever travel and “feel” than; did previous Honda hydraulic brakes. It is almost impossible to lock the Iront wheel during a panic stop, unless you have a superhuman grip, and even after duplicating our 60-to-0-mph panic stop several times, practically no fade was evident. The rear brake is exactly the same as the unit used on the twin-cylinder CB450 and performs in an exemplary manner. Required pedal pressure was only moderate, thus, in moments ot trepidation, one can press on the pedal firmly without fear of locking the rear wheel. Directional control during a panic stop was more like what you would expect from a four shoe front brake with a backing plate anchored to each fork leg; there was almost no pull to one side upon application of the front brake.

All controls, with the possible exception of the ignition switch, which is below the fuel tank on the left-hand side, are well placed and easy to operate. The medium-high-rise handlebars provide good control and a comfortable riding position, but are a little too high for a rider of average height or above for high speed cruising. The high placement of the handlebars makes the rider sit almost bolt upright into the wind definitely tiring on long trips. All thumb operated switches are within easy reach of the handlebar grips, and again present is Honda’s off-on-off switch located on top of the throttle side mechanism. A simple Hick of this switch in either direction shuts off electrical power to the high tension coils and stops the engine.

Handling qualities are very nearly excellent with the main complaint stemming from the rear suspension units. Slow speed steering is vastly improved over the CB750, which makes threading one’s way through 5 o’clock traffic a delight. Good front end geometry makes fast sweeping curves easy to negotiate, and only a slight trace of indecision is transmitted through the handlebars. In terms of effort required, steering felt almost neutral. Merely a hint at the handlebars is all that is required to make the machine turn. There is no tendency to “fall into” or go wide, once the angle of lean has been established.

The 500’s smaller version of the CB750’s front forks irons out road imperfections, and exhibits ideal spring rate and damping characteristics. The rear suspension units are quite disappointing, however, as the spring rate is a little too soft and there is not nearly enough rebound damping. Increasing the spring tension by means of the three-stepped cam ring only partially alleviated the problem, as riding double produced bottoming—along with the loathsome “rocking chair” effect after the bump was hit—on only medium sized holes in the road. No steering damper is fitted, nor did we feel the need for one.

Most of the credit for the CB 500’s roadholding qualities is directly attributable to the frame. Virtually a scaled-down version ot the CB750 frame, it is of the double cradle variety with a large maintube bolstered by two smaller top rails which extend rearward to form the top rails of the rear frame assembly, providing a mounting point for the tops of the shock absorbers. A long, heavy swinging arm unit is fabricated from two heavy stampings to resist flexing, and the front mounting pivot area is heavily gusseted. For a completely automatically assembled frame, welding is close to perfect.

Detailing and overall finish is of the highest quality, as has become standard fare with Honda. Chrome plating is heavily applied and paintwork is letter perfect. A panel of “idiot lights” mounted just above the center of the handlebars keeps the rider informed about the status of turn signals, oil pressure, neutral position and high beam, thus removing these items from the speedometer and tachometer faces.

The electrical components perform beautifully and are of the highest quality. The headlamp’s ideally shaped beam patterns make it more than satisfactory for high speed riding at night, and the high wattage bulbs all over the motorcycle provide more than ample illumination in the correct places. A 12V/12AH battery provides the power to spin the starter and operate the lights and turn signals, and the generator has sufficient power to drive auxiliary lights if desired.

A nice feature that we haven’t seen before is the helmet lock under the seat. Actually, it’s just two hooks under the scat through which the helmet straps may be run. Then, the seat can be lowered and locked into position, preventing theft of one’s helmet and tools. The toolkit, too, is of above average quality, and contains feeler gauges and an ignition point file in addition to tools required for routine maintenance.

All told, the Honda CB500 is perhaps the finest combination of superb engineering and deluxe features we’ve ever come across. Virtually vibration free performance, high cruising speed, spirited acceleration, good handling qualities, excellent fuel economy, etc., etc. We could go on forever, and with a retail price of $1345, Honda probably will too! [Oj

HONDA CB500 FOUR

$1345

View Full Issue

View Full Issue