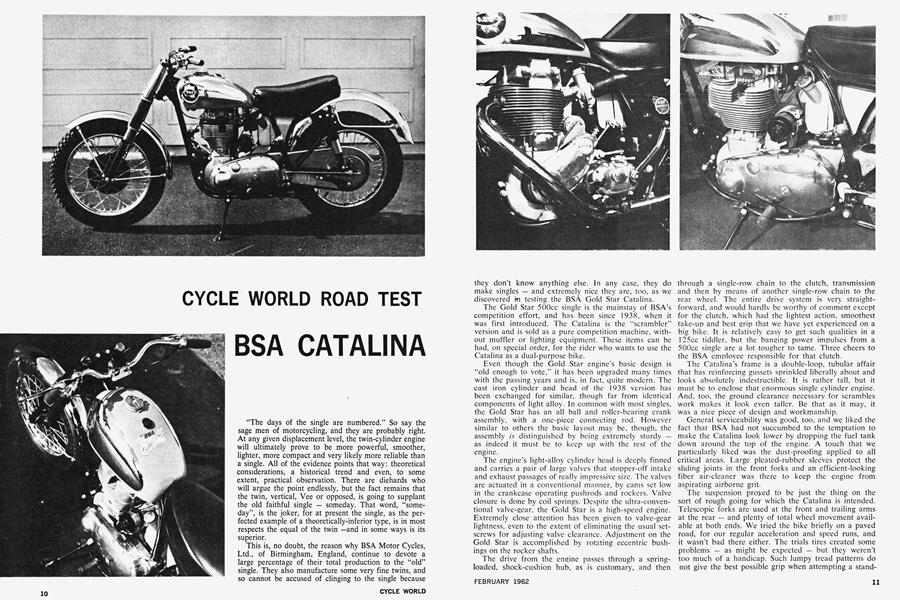

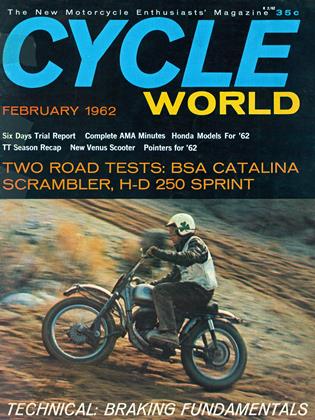

BSA CATALINA

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

“The days of the single are numbered.” So say the sage men of motorcycling, and they are probably right. At any given displacement level, the twin-cylinder engine will ultimately prove to be more powerful, smoother, lighter, more compact and very likely more reliable than a single. All of the evidence points that way: theoretical considerations, a historical trend and even, to some extent, practical observation. There are diehards who will argue the point endlessly, but the fact remains that the twin, vertical, Vee or opposed, is going to supplant the old faithful single — someday. That word, “someday”, is the joker, for at present the single, as the perfected example of a theoretically-inferior type, is in most respects the equal of the twin —and in some ways is its superior.

This is, no doubt, the reason why BSA Motor Cycles, Ltd., of Birmingham, England, continue to devote a large percentage of their total production to the “old” single. They also manufacture some very fine twins, and so cannot be accused of clinging to the single because they don’t know anything else. In any case, they do make singles — and extremely nice they are, too, as we discovered m testing the BSÁ Gold Star Catalina.

The Gold Star 500cc single is the mainstay of BSA’s competition effort, and has been since 1938, when it was first introduced. The Catalina is the “scrambler” version and is sold as a pure competition machine, without muffler or lighting equipment. These items can be had, on special order, for the rider who wants to use the Catalina as a dual-purpose bike.

Even though the Gold Star engine’s basic design is “old enough to vote,” it has been upgraded many times with the passing years and is, in fact, quite modern. The cast iron cylinder and head of the 1938 version has been exchanged for similar, though far from identical components of light alloy. In common with most singles, the Gold Star has an all ball and roller-bearing crank assembly, with a one-piece connecting rod. However similar to others the basic layout may be, though, the assembly is distinguished by being extremely sturdy — as indeed it must be to keep up with the rest of the engine.

The engine’s light-alloy cylinder head is deeply finned and carries a pair of large valves that stopper-off intake and exhaust passages of really impressive size. The valves are actuated in a conventional manner, by cams set low in the crankcase operating pushrods and rockers. Valve closure is done by coil springs. Despite the ultra-conventional valve-gear, the Gold Star is a high-speed engine. Extremely close attention has been given to valve-gear lightness, even to the extent of eliminating the usual setscrews for adjusting valve clearance. Adjustment on the Gold Star is accomplished by rotating eccentric bushings on the rocker shafts.

The drive from the engine passes through a springloaded, shock-cushion hub, as is customary, and then through a single-row chain to the clutch, transmission and then by means of another single-row chain to the rear wheel. The entire drive system is very straightforward, and would hardlv be worthy of comment except for the clutch, which had the lightest action, smoothest take-up and best grip that we have yet experienced on a big bike. It is relatively easy to get such qualities in a 125cc tiddler, but the bansing power impulses from a 500cc single are a lot tougher to tame. Three cheers to the BSA employee responsible for that clutch.

The Catalina’s frame is a double-loop, tubular affair that has reinforcing gussets sprinkled liberally about and looks absolutely indestructible. It is rather tall, but it must be to enclose that enormous single cylinder engine. And, too, the ground clearance necessary for scrambles work makes it look even taller. Be that as it may, it was a nice piece of design and workmanship.

General serviceability was good, too, and we liked the fact that BSA had not succumbed to the temptation to make the Catalina look lower by dropping the fuel tank down around the top of the engine. A touch that we particularly liked was the dust-proofing applied to all critical areas. Large pleated-rubber sleeves protect the sliding joints in the front forks and an efficient-looking fiber air-cleaner was there to keep the engine from aspirating airborne grit.

The suspension proyed to be just the thing on the sort of rough going for which the Catalina is intended. Telescopic forks are used at the front and trailing arms at the rear — and plenty of total wheel movement available at both ends. We tried the bike briefly on a paved road, for our regular acceleration and speed runs, and it wasn't bad there either. The trials tires created some problems — as might be expected — but they weren’t too much of a handicap. Such lumpy tread patterns do not give the best possible grip when attempting a standing-start sprint, and our 14 -mile times suffered a bit as a consequence. The trials tires are, naturally, not the best thing to have on a paved surface, but they aren’t as limited in usefulness as some of the knobbed tires one sees at cross-country events. Anyway, the Catalina, equipped with lights and a muffler, could be used for limited touring.

Brakes are probably not all that important on a scrambler but it is nice to know that you have them — and on the Catalina, you really do. The drums are smaller than on the Clubman (road racing) version, but only slightly, at 7" x lVs" (diameter and width). They are lighter and more powerful than anything you could ever want for dirt-riding, and ample for any incidental road work, as well.

The overall finish on the Catalina, especially on those parts that are chrome-plated, is exceedingly good. This says quite a lot, too, if you consider that most of the fuel tank, the fenders, and most of the miscellaneous bits and pieces are plated. The effect could be a trifle gaudy, and would be on a less purposeful-looking machine. The super-abundance of chrome does serve a purpose; repeated contact with tree-branches, brush and flying sand and gravel will not mar the finish — as they surely would with paint.

Starting, once we found the right combination, was always reasonably quick and easy. It would be foolish for us to tell you that pumping that big piston up and down is something any twelve-year-old Girl Scout could manage. That is nonsense. You have to use the compression release to get the engine cranked around to an easy spot, and then really lean on it. Determination, more than brute force, is actually the deciding factor and even a light rider will have little trouble once he gets the knack — but a fair amount of vigor is necessary. We should make it perfectly clear, though, that the Gold Star engine is not balky — it just needs a firm hand (or foot.)

While thundering along through the “boondocks”, the saddle struck us (literally) as being very comfortable.

Suspension systems, however good, can absorb just so much of the bumping and the rest has to be taken up in the compression of the saddle and the human hindside. Needless to say, it is better if the jolting can be absorbed by the former, rather than the latter, and on the Catalina this was mostly true.

The handlebars, like the tires, struck a compromise between being suited for soft or hard surface riding. For all around use they were excellent, but we are of the opinion that for the high-speed sand-hill racing that is so popular here in America a set of slightly flatter bars would have been better. On a less willing machine this would have been a very minor point, but the Catalina will blast along, up to the spokes in sand, at speeds one would think high even on the best of surfaces. In doing this, and discovering that a big handful of throttle would send up a “roostertail” of sand.

It can be said of the Catalina, that it will go any place the rider has the intestinal fortitude to attempt. The only times we failed to get to an objective, however impossible, was when the machine just sank out of sight in the soft stuff. It was a sight to see, too, with all the flying sand and the Catalina apparently on its way to China — the hard way.

On reasonably hard surfaces the Catalina showed itself to be made of more willing stuff than our test crew. It may have had some sort of a maximum stable velocity out in the rough, but we never found it. It was grand fun, charging along with the megaphone blaring and the brush whipping by — and then we would get to that point, the one where the smell of linament and adhesive tape begins to creep into one's nostrils.

Although the proper evaluation of a machine like the Catalina is only made on the race course, we think that this one, like the BSA Gold Stars of years past, is a real dandy. It is fast, incredibly smooth and makes fewer of those threshing sounds from within than anything else in the scope of our experience. When you ride the Catalina, the thought comes to mind that perhaps these two-cylinder rigs are just a fad afterall.

BSA CATALINA

$1,045

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cycle Round Up

February 1962 -

The Service Department

February 1962 By Gordon H. Jennings -

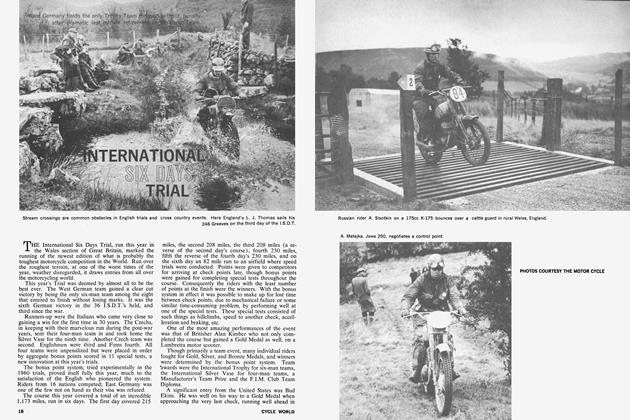

International Six Days Trial

February 1962 -

Technical

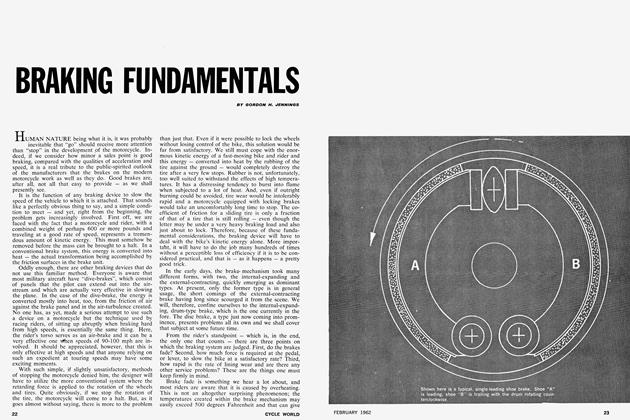

TechnicalBraking Fundamentals

February 1962 By Gordon H. Jennings -

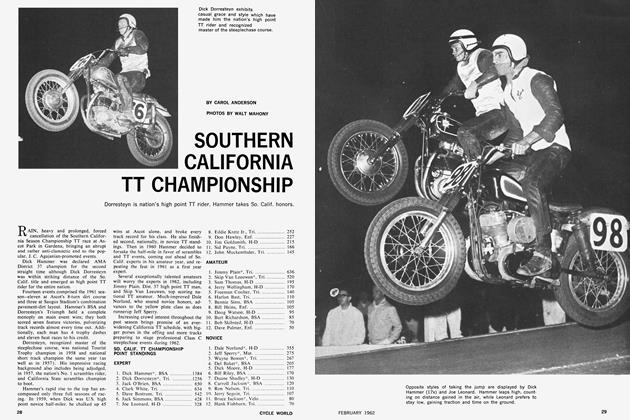

Southern California Tt Championship

February 1962 By Carol Anderson -

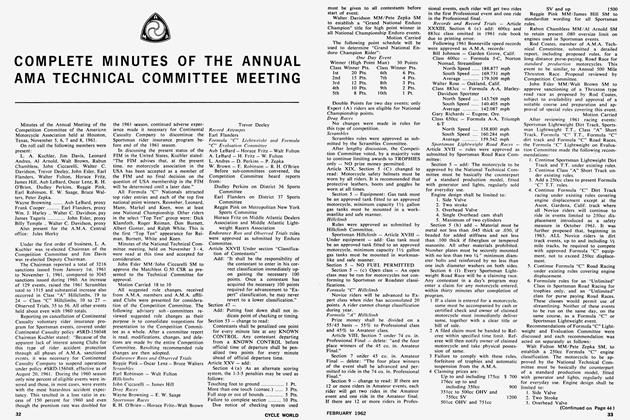

Complete Minutes of the Annual Ama Technical Committee Meeting

February 1962