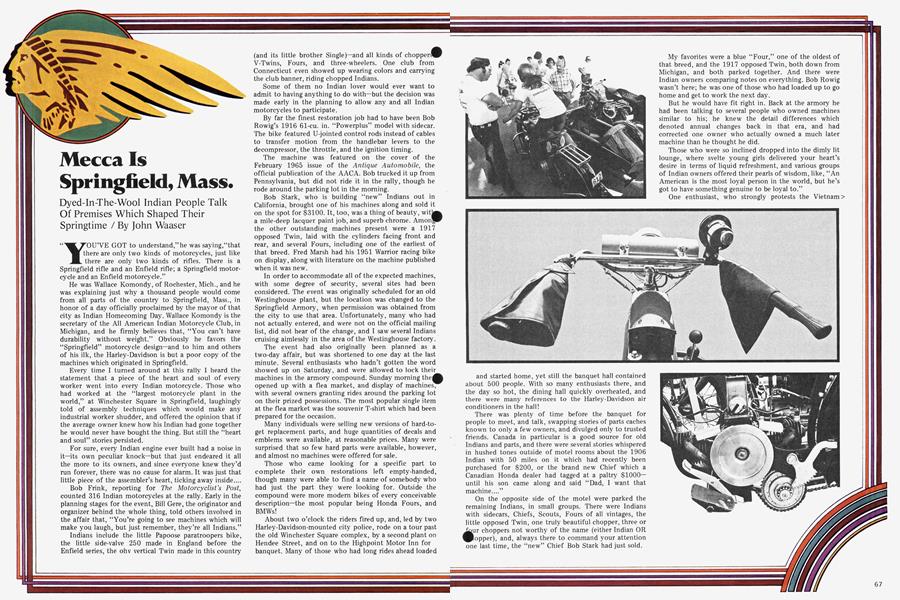

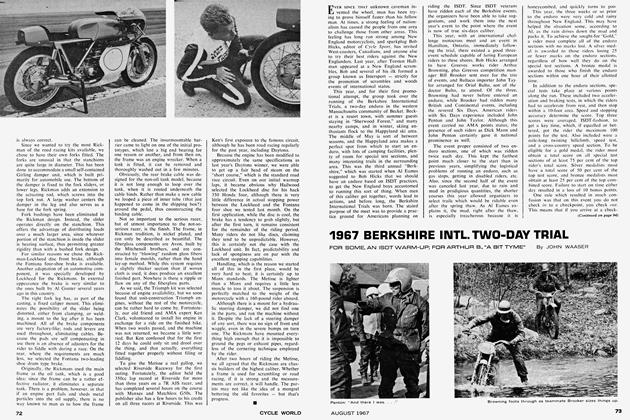

Mecca Is Springfield, Mass.

Dyed-In-The-Wool Indian People Talk Of Premises Which Shaped Their Springtime

John Waaser

Y0U'VE GOT to understand," he was saying,"that there are only two kinds of motorcycles, just like there are only two kinds of rifles. There is a Springfield rifle and an Enfield rifle; a Springfield motorcycle and an Enfield motorcycle."

He was Wallace Komondy, of Rochester, Mich., and he was explaining just why a thousand people would come from all parts of the country to Springfield, Mass., in honor of a day officially proclaimed by the mayor of that city as Indian Homecoming Day. Wallace Komondy is the secretary of the All American Indian Motorcycle Club, in Michigan, and he firmly believes that, “You can’t have durability without weight.” Obviously he favors the “Springfield” motorcycle design—and to him and others of his ilk, the Harley-Davidson is but a poor copy of the machines which originated in Springfield.

Every time I turned around at this rally I heard the statement that a piece of the heart and soul of every worker went into every Indian motorcycle. Those who had worked at the “largest motorcycle plant in the world,” at Winchester Square in Springfield, laughingly told of assembly techniques which would make any industrial worker shudder, and offered the opinion that if the average owner knew how his Indian had gone together he would never have bought the thing. But still the “heart and soul” stories persisted.

For sure, every Indian engine ever built had a noise in it—its own peculiar knock—but that just endeared it all the more to its owners, and since everyone knew they’d run forever, there was no cause for alarm. It was just that little piece of the assembler’s heart, ticking away inside....

Bob Frink, reporting for The Motorcyclist's Post, counted 316 Indian motorcycles at the rally. Early in the planning stages for the event, Bill Gere, the originator and organizer behind the whole thing, told others involved in the affair that, “You’re going to see machines which will make you laugh, but just remember, they’re all Indians.” Indians include the little Papoose paratroopers bike, the little side-valve 250 made in England before the Enfield series, the ohv vertical Twin made in this country (and its little brother Single)—and all kinds of choppers^^ V-Twins, Fours, and three-wheelers. One club from Connecticut even showed up wearing colors and carrying the club banner, riding chopped Indians.

Some of them no Indian lover would ever want to admit to having anything to do with—but the decision was made early in the planning to allow any and all Indian motorcycles to participate.

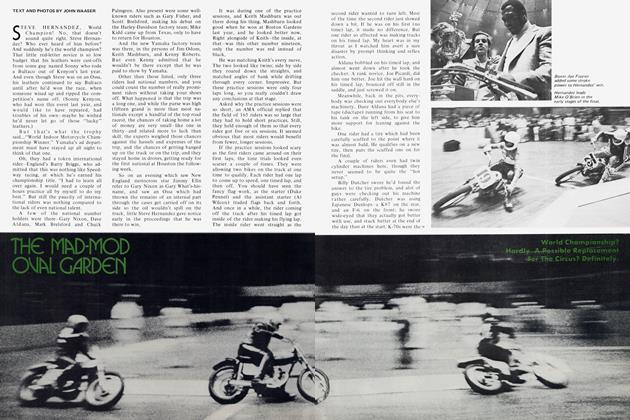

By far the finest restoration job had to have been Bob Rowig’s 1916 61-cu. in. “Powerplus” model with sidecar. The bike featured U-jointed control rods instead of cables to transfer motion from the handlebar levers to the decompressor, the throttle, and the ignition timing.

The machine was featured on the cover of the February 1965 issue of the Antique Automobile, the official publication of the AACA. Bob trucked it up from Pennsylvania, but did not ride it in the rally, though he rode around the parking lot in the morning.

Bob Stark, who is building “new” Indians out in California, brought one of his machines along and sold it on the spot for $3100. It, too, was a thing of beauty, WRIÄ a mile-deep lacquer paint job, and superb chrome. Amonf^ the other outstanding machines present were a 1917 opposed Twin, laid with the cylinders facing front and rear, and several Fours, including one of the earliest of that breed. Fred Marsh had his 1951 Warrior racing bike on display, along with literature on the machine published when it was new.

In order to accommodate all of the expected machines, with some degree of security, several sites had been considered. The event was originally scheduled for an old Westinghouse plant, but the location was changed to the Springfield Armory, when permission was obtained from the city to use that area. Unfortunately, many who had not actually entered, and were not on the official mailing list, did not hear of the change, and I saw several Indians cruising aimlessly in the area of the Westinghouse factory.

The event had also originally been planned as a two-day affair, but was shortened to one day at the last minute. Several enthusiasts who hadn’t gotten the word showed up on Saturday, and were allowed to lock their machines in the armory compound. Sunday morning the^fc opened up with a flea market, and display of machines^ with several owners granting rides around the parking lot on their prized possessions. The most popular single item at the flea market was the souvenir T-shirt which had been prepared for the occasion.

Many individuals were selling new versions of hard-toget replacement parts, and huge quantities of decals and emblems were available, at reasonable prices. Many were surprised that so few hard parts were available, however, and almost no machines were offered for sale.

Those who came looking for a specific part to complete their own restorations left empty-handed, though many were able to find a name of somebody who had just the part they were looking for. Outside the compound were more modern bikes of every conceivable description—the most popular being Honda Fours, and BMWs!

About two o’clock the riders fired up, and, led by two Harley-Davidson-mounted city police, rode on a tour past the old Winchester Square complex, by a second plant on Hendee Street, and on to the Highpoint Motor Inn for banquet. Many of those who had long rides ahead loaded and started home, yet still the banquet hall contained about 500 people. With so many enthusiasts there, and the day so hot, the dining hall quickly overheated, and there were many references to the Harley-Davidson air conditioners in the hall!

There was plenty of time before the banquet for people to meet, and talk, swapping stories of parts caches known to only a few owners, and divulged only to trusted friends. Canada in particular is a good source for old Indians and parts, and there were several stories whispered in hushed tones outside of motel rooms about the 1906 Indian with 50 miles on it which had recently been purchased for $200, or the brand new Chief which a Canadian Honda dealer had tagged at a paltry $1000— until his son came along and said “Dad, I want that machine....”

On the opposite side of the motel were parked the remaining Indians, in small groups. There were Indians with sidecars, Chiefs, Scouts, Fours of all vintages, the little opposed Twin, one truly beautiful chopper, three or

§ur lopper), choppers and, not always worthy there of to the command name (either your Indian attention OR one last time, the “new” Chief Bob Stark had just sold. My favorites were a blue “Four,” one of the oldest of that breed, and the 1917 opposed Twin, both down from Michigan, and both parked together. And there were Indian owners comparing notes on everything. Bob Rowig wasn’t here; he was one of those who had loaded up to go home and get to work the next day.

But he would have fit right in. Back at the armory he had been talking to several people who owned machines similar to his; he knew the detail differences which denoted annual changes back in that era, and had corrected one owner who actually owned a much later machine than he thought he did.

Those who were so inclined dropped into the dimly lit lounge, where svelte young girls delivered your heart’s desire in terms of liquid refreshment, and various groups of Indian owners offered their pearls of wisdom, like, “An American is the most loyal person in the world, but he’s got to have something genuine to be loyal to.”

One enthusiast, who strongly protests the Vietnam > war, admitted he’d be the first one to grab arms if the war ever came to American soil. A lot of names and addresses were exchanged, along with promises to get together at some future date; maybe to break out the Indians and go for a ride, like in the old days; maybe just a drink; maybe to hunt for parts; maybe to lovingly restore a badly rusted fender. Loyalty. No Harley owner could ever be more loyal.

But if you believe that the only motorcycles are Springfield motorcycles and Enfield motorcycles, then perhaps the Indian enthusiast does have something more genuine to be loyal to. And then it’s ironical that the demise of the Indian came about when they started selling Enfield motorcycles—both the American-made vertical Twin Warrior, and the British-built Enfield Chief, and their derivatives.

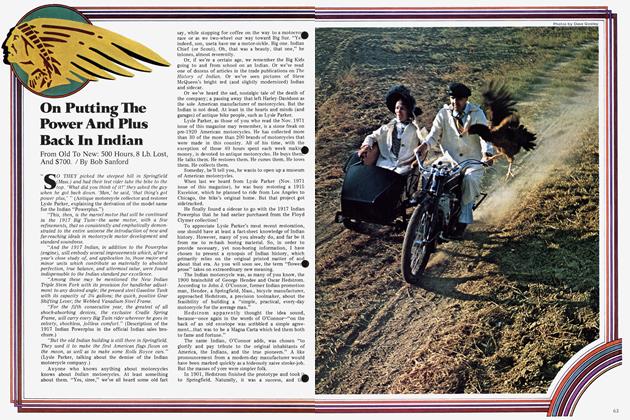

Without any genuine signal, everybody began filinj^ into the upstairs banquet hall, for their choice of chicken or roast beef dinners, topped off with strawberry shortcake. At the head table sat Bill Gere, whose idea brought the day into being, Master of Ceremonies Fritzie Baer (“It takes a hell of a lot of nerve for an old man of 71 to wear a red hat”), Springfield water commissioner Charles Manthis, who had in large part been responsible for the official recognition of the day, “Pop” Armstrong, one of the most famous Indian riders of all time, and other dignitaries. Jules Horky and Jim Davis, both AMA staffers, were there, Jules as a former Indian employee, and Jim as a 1916 racer of some repute.

Said Davis, “To go by this plant, and see it the way it is today, it makes your heart ache.” The Winchester Square plant, since used (among other things) as a furniture store, is rumored to be slated for demolition in the near future.

Jimmy Hill, the factory engineer who is known as, “The guy who made the Scout famous,” noted that he recognized Indian employees of 40 years ago in the audience—and then said that they had more people he^B than they had at the Indian employee banquets, years ago. He relived such Indian greats as George Holden’s San Francisco to New York record of 31 days, 12 hours, 15 minutes—some 35 hours faster than the then-current automobile record.

“Pop” Armstrong rose to great applause, noting that he was 84 years young, and that this was a bright spot in his life. He talked of the fight for the right to ride off the> road. “Stick togetheir-you’re going to win!” he said, and received a standing ovation for it.

John Wykham, president of the Indian Four Club, who was in the hospital, and couldn’t attend, sent his regards. Leonard Reed, better known to Indian enthusiasts as “King Kong,” a huge colored dude from New York City, then got up to take a bow for some of his record-holding Indian rides, and exchanged pleasantries with others he knew. He still looks fit enough to do it right now, if Indians ever come back....

Then it was time for the National Motorcycle Helmet Committee Inc. to say its piece. The spirit of this crowd, all of whom rode Indians in the days when they used leather helmets to keep their hair in place, or let it fly in the wind, was amazingly receptive to this group which

tally has gotten the helmet case into the federal courts, uck Myles, who put a lot of effort into organizing the meet, even though he lives a hundred miles away, had donated an unrestored, but running, Indian four, on which the Helmet Committee was selling chances at $2.50 each. They took in over $600 on the effort, while many of those present, caught in the fever pitch, were buying blocks of tickets in the last minutes before the drawing. Fritzie Baer related a story of his son, who told Fritzie that he couldn’t afford a helmet, then crashed, wearing one, and said, “Dad, I know what you mean.” Yet Fritzie himself stopped riding partly because of the government coercion to wear helmets. He drew a big ovation when he blasted the merry men in Washington who don’t know anything about motorcycles. There were both young and old enthusiasts present, and on this one issue, there is truly no generation gap.

About the time Arthur Rogers, one-time secretary of the Indian Motorcycle Company—officially spelled without the “r”—got up to speak, they called for a hand count

«former nds, perhaps Indian a dozen employees. or so, but Not one too who many both raised raised their her hand and her voice, to make sure everyone knew, was one of the waitresses from the Highpoint Motor Inn. She had worked for one of the engineering brass, during the last years of the company’s existence, and here she was working now so that her former co-workers and fellow enthusiasts could eat.

Rogers said that it was the customers who made the company successful; his one lament was that those who were here tonight were not that loyal when the company was going under. He closed by reciting an old ditty:

“You can’t wear out an Indian Scout,

Or its brother the Indian Chief.

They’re built like rocks to withstand hard knocks,

It’s the Harleys that cause the grief.”

With that, Sammy Pierce put in a word about the air conditioner, which definitely, he opined, must have been made in Milwaukee. He introduced Bob Stark, and noted that if they didn’t have an Indian part somebody needed, between the two of them, they’d make it. And he added his own favorite ditty:

“Harley-Davidson, made of tin.

Ride them out, and push them in.”

Loyalty. The Springfield motorcycle. American engineering parameters applied to motorcycling. It all explains why 1000 people would lug 316 old motorcycles from all parts of the country and Canada to attend a rally in honor of a motorcycle which has been out of production almost 20 years. And it also explains why, as “Pop” Armstrong put it, “They’re going to have to bury Indians with every person I’ve seen today.”