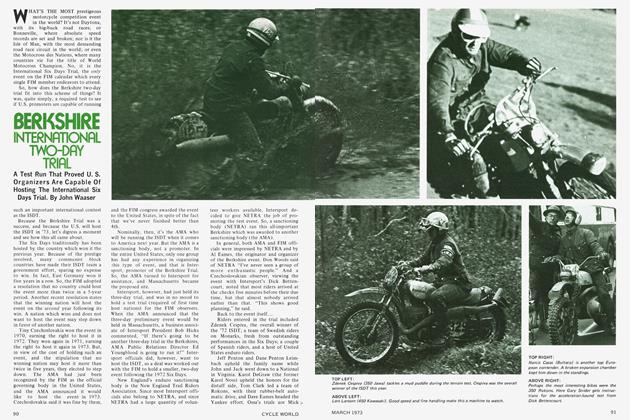

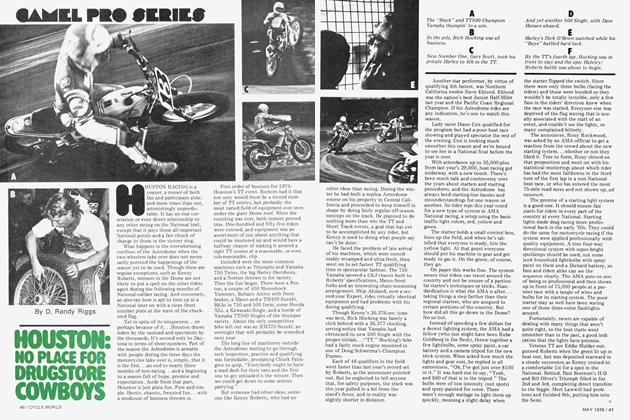

"Make That A Double, Please”

...Gary Nixon At Loudon

JOHN WAASER

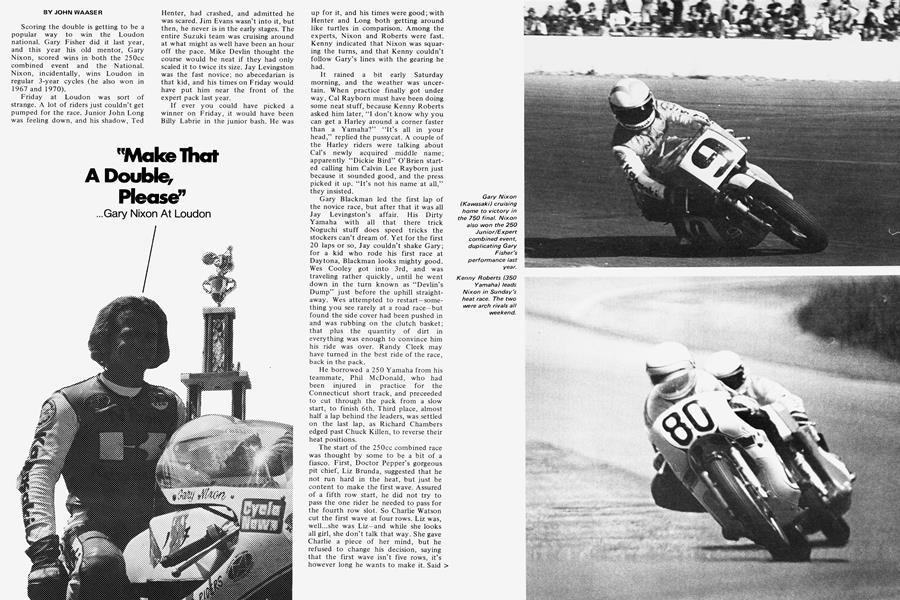

Scoring the double is getting to be a popular way to win the Loudon national. Gary Fisher did it last year, and this year his old mentor, Gary Nixon, scored wins in both the 250cc combined event and the National. Nixon, incidentally, wins Loudon in regular 3-year cycles (he also won in 1967 and 1970).

Friday at Loudon was sort of strange. A lot of riders just couldn’t get pumped for the race. Junior John Long was feeling down, and his shadow, Ted Henter, had crashed, and admitted he was scared. Jim Evans wasn’t into it, but then, he never is in the early stages. The entire Suzuki team was cruising around at what might as well have been an hour off the pace. Mike Devlin thought the course would be neat if they had only scaled it to twice its size. Jay Levingston was the fast novice; no abecedarian is that kid, and his times on Friday would have put him near the front of the expert pack last year.

If ever you could have picked a winner on Friday, it would have been Billy Labrie in the junior bash. He was up for it, and his times were good; with Henter and Long both getting around like turtles in comparison. Among the experts, Nixon and Roberts were fast. Kenny indicated that Nixon was squaring the turns, and that Kenny couldn’t follow Gary’s lines with the gearing he had.

It rained a bit early Saturday morning, and the weather was uncertain. When practice finally got under way, Cal Rayborn must have been doing some neat stuff, because Kenny Roberts asked him later, “I don’t know why you can get a Harley around a corner faster than a Yamaha?” “It’s all in your head,” replied the pussycat. A couple of the Harley riders were talking about Cal’s newly acquired middle name; apparently “Dickie Bird” O’Brien started calling him Calvin Lee Rayborn just because it sounded good, and the press picked it up. “It’s not his name at all,” they insisted.

Gary Blackman led the first lap of the novice race, but after that it was all Jay Levingston’s affair. His Dirty Yamaha with all that there trick Noguchi stuff does speed tricks the stockers can’t dream of. Yet for the first 20 laps or so, Jay couldn’t shake Gary; for a kid who rode his first race at Daytona, Blackman looks mighty good. Wes Cooley got into 3rd, and was traveling rather quickly, until he went down in the turn known as “Devlin’s Dump” just before the uphill straightaway. Wes attempted to restart —something you see rarely at a road race—but found the side cover had been pushed in and was rubbing on the clutch basket; that plus the quantity of dirt in everything was enough to convince him his ride was over. Randy Cleek may have turned in the best ride of the race, back in the pack.

He borrowed a 250 Yamaha from his teammate, Phil McDonald, who had been injured in practice for the Connecticut short track, and preceeded to cut through the pack from a slow start, to finish 6th. Third place, almost half a lap behind the leaders, was settled on the last lap, as Richard Chambers edged past Chuck Killen, to reverse their heat positions.

The start of the 250cc combined race was thought by some to be a bit of a fiasco. First, Doctor Pepper’s gorgeous pit chief, Liz Brunda, suggested that he not run hard in the heat, but just be content to make the first wave. Assured of a fifth row start, he did not try to pass the one rider he needed to pass for the fourth row slot. So Charlie Watson cut the first wave at four rows. Liz was, well...she was Liz—and while she looks all girl, she don’t talk that way. She gave Charlie a piece of her mind, but he refused to change his decision, saying that the first wave isn’t five rows, it’s however long he wants to make it. Said Liz of Charlie, “To him all girls look alike—they’re the ones without the beards.”

Back to the race. Gary Fisher, the drag specialist of the Yamaha factory squad, got the early lead. That doesn’t mean he could hold onto it, however. Loudon is Gary Nixon’s track, and this was the third year since his last win here. It was time. Gary grabbed the lead on the fifth lap, and worked the corners so hard I expected them to go on strike for more money. By the eighth lap or so, it was definitely raining, though lightly. The track didn’t look wet, yet, but the riders could see drops on their windshields. Everyone expected the officials to call the race as soon as they could have an official finish. Nixon had built himself quite a cushion by the 12th lap, when Squirrly Wilvert went down. The red flag came out on the 13th lap, and the bikes were brought into the pits to await a decision on the restart.

Roberts complained of his front brake, which was getting hard to pull, and the mechanics immediately went to work on it. Fisher decided a change of gearing and some other stuff was in order, and they hopped to that. Nixon’s bike was doing fine, thank you, and they left it alone.

Finally, the decision was made to restart the race on Sunday—though at the time, Sunday’s weather forecast was far worse than Saturday’s, and Sunday already had scheduled the Junior race, a special sidecar exhibition, and the National races (two heats, a semi, and a final).

At Sunday’s riders’ meeting, Charlie announced that the restart would be single-file, nose-to-tail, with no time interval between the riders. This meant that Gary would lose the lead he had built up. His opponents also had been allowed to work on their bikes—to change gearing, or anything else they wanted to do, for that matter. Charlie explained that there would have been too many problems trying to impound all the bikes. When Gary Nixon asked why there would be no time interval between the bikes, as there had been four years ago, Charlie replied, “It’s a different ball game.” Gary quickly shot back, “Same ball.” But Charlie was adamant. Finally a compromise was reached; the starter would run down the line, giving a distince flag to each rider, with a uniform time interval. This at least minimized the possibility of a collision on the restart. Duke Pennell, the starter, arrived at the meeting a little late. Charlie told him of the agreed upon start, and Duke balked; he refused to go along with the idea. Back to a single flag for everybody. They were going to try to enforce a “no passing before the start/finish line” rule, but the riders objected to that. Riders would be lined up as they crossed the finish line on the 12th lap. Anybody who got by another rider on the 13th lap would have to do it all over again.

Gary Fisher again won the drag race, but faded fast, and Nixon had his lead back. Roberts closed on him, and started pressing, and these two raced closely, with Roberts obviously on the faster bike, and Nixon still working the corners 24 hours a day. Long, Henter, and Labrie, the three top juniors, were right together, too, until the slide fell out of Henter’s carb, necessitating repairs, and Long managed to pull away from Labrie. About four laps from the end, Nixon closed on Roberts, and began a do-or-die struggle. Just before the white flag, Labrie slid off in the last turn. He got back up without even stalling it, but his front brake lever was broken; he rode the last lap without it, and finished 10th.

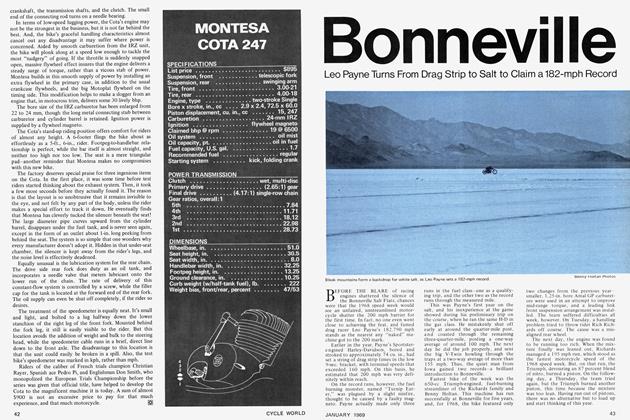

The last lap. That was a corker; nobody’s going to forget that one. Nixon led, Roberts passed him. They went into the hairpin side by side, and Kenny’s line forced Gary a little wide. Kenny had a good lead of several lengths going down the chute to the last turn. Gary had lost a hard-fought race. But Gary wasn’t through yet; he had to win this one. There are those who believe that Gary would have centerpunched Kenny in the last turn if necessary. Gary screamed in sooooo deep, and he forced Kenny a couple of feet off his line. Gary squared it, and scooted to the flag while Kenny was still trying to figure out which way the last turn went. Fisher was about nine seconds back in 3rd.

Earlier Sunday morning, in the big bike practice, Gary Scott had hoped to get into the 15s (1 min. 15 sec. per lap), and felt that the race winner would average in the high 13s. Scott’s bike was an American built machine, while Mann and Romero had the original English built bikes. In order to achieve competitive power, Scott’s bike was running Amal GP carbs, while the british-tuned engines could get by with monoblocs. Gary had 2lA more horses on top, but it wouldn’t pull as cleanly after it had been shut off for a corner. Gary also had the lower gas tank which had been fitted for Road Atlanta, while Buggs and Burrito were running the higher Daytona tanks. Danny Macias explained that these two preferred the higher tanks, which gave more body support during the frequent hard braking on this tight course.

Two Harleys had been set up with number 14 on the fairings. One was Cal’s own bike, the other was Mark Brelsford’s Daytona machine. Cal’s was faster, but Mark’s handled better. They

Loudon swapped the mag wheels and other trick parts from Mark’s to Cal’s bike, so Cal could have the best of both worlds.

Pat Hennen, the junior who rides the Ron Grant Racing Specialties Suzuki Twin had been turning as fast as the factory Triples in practice, and Ron was giving him some instructions in the psychology of racing. “Ride the race; don’t get caught watching other guys,” cautioned Ron. He related an experience of his last winter, where he automatically assumed the braking points and lines of a slower rider in front of him, and couldn’t get by until something forced him to use his own lines again.

Gary Fisher got the early lead in the first expert heat, with Yvon Duhamel in 2nd. Steve McLaughlin was running his Harry Hunt Yamaha without the fairing, and he caught up to Cliff Carr. These two then passed Cal Rayborn, who started dropping well back. Ron Pierce was in 3rd, and Steve McLaughlin got outside Carr in the hairpin for fourth. Gary Scott, in 6th, had a good lead over Geoff Perry, the best factory Suzuki. DuHamel came up alongside of Fisher in the hairpin, but miraculously, Gary kept his lead. The Flying Frenchman just pipped Gary at the flag for the first heat win. Scott moved up into 4th.

In the second heat, Nixon and Roberts played a rematch of their pass-and-repass game, with Jim Allen a fading 3rd. It was a neat race for first, with Gary finally getting a good lead on the next to last lap. The semi was won by a BMW. (See how neat that sounds The semi pitted the slowest riders— those who had not qualified in the heats, but Reg Pridmore on the BeEm won it, so he sounds fast. Not that the BMWs are so slow; don’t get that impression. Kurt Liebmann finished the final in 13th place, on what is really a neat effort; all properly “worksy” with Kayser 5 gang transmissions, and a nifty dashboard for the instruments.)

Phil McDonald, the Daytona junior winner, had injured his left foot in a short track race. He passed up the 250 race, and had moved both the shift and brake to the right side on his 350. But he figured the tech crew wouldn’t buy that so he moved the brake over to the left, but his foot hurt so bad he couldn’t use it. Still, both worked, and he passed tech, with the officials blissfully unaware that he would be riding the race without a rear brake. Mike Devlin came to the line without a pit helper. “How’s he going to start the bike” I didn’t have long to wonder. He just sat on it, dangled his spidery legs, and started walking. As the bike gathered momentum, he popped the clutch. Instant start. Neat.

A few minutes later, they were off. Billy Labrie, our predicted winner, slid into an early lead, and pulled a healthy gap over 2nd as he started slicing through traffic. Long pulled away from Henter, in 2nd. Tim Rockwood had second off the line, but faded fast, and pulled off after he sucked a gasket and started lubricating the rear tire. Long started gaining on Labrie; was Long getting faster, or was Billy slowing down? “I slowed down,” said Bill later, pointing to a worn front tire. You don’t want to start the heat or the final on a new tire, because you’ll waste precious laps breaking it in. But if you start the heat on one with, say, 40-50 miles on it, you might not finish the race with good rubber. The track was rough; it was hard on tires—though the only riders with complaints were the Yamaha riders. The three Florida juniors are so much faster than the Californians that 2nd place Labrie had almost lapped fourth place Devlin at the flag. Mike was a bit surprised that he did so well. He’s not too good at “dialing it in;” the 350 requires more finesse, and he usually fares better on his 250.

Following the junior race, Brian Dalgarno, the younger brother of Gary Nixon’s sponsored rider, was awarded a $500 scholarship by the Rusty Bradley Scholarship foundation. Quipped Bryan, “That’s more money than I’ve made in AMA racing....”

Dave Aldana had gone back to Maryland with Steve Dalgarno after the Thursday night short track, but showed up at Loudon on Sunday morning, practiced, and raced. Dave, and Steve McLaughlin, did Loudon without fairings. The extra weight of a fairing hampers acceleration, and doesn’t really help until you get near top end. Top speeds at Loudon might be 120 for the super bikes, but not much over the ton, or maybe a buck-ten for the slower machines. The use of a fairing is a moot point, and with the braking and cornering, crawling under the fairing, and then out again, is a hassle. Aldana had yet another reason for not running the fairing, however. He had wiped his out at Road Atlanta.

Nixon’s bike, epoxy and all, was still running well, and he scooted to an early lead, passing Roberts, with a longish gap to Gary Scott, after Jim Allen, the very early 3rd, faded. Yvon Duhamel had been the earliest 3rd place rider, but pitted on the second lap, to have a throttle cable repaired. He re-entered the fray, but the cylinder which had been dragged along by the other two had run lean, and scorched the piston, and he retired.

The first three positions, then, were determined very early in the game. Scott knew he had to finish right behind, or preferably ahead of, Roberts. But he also knew Roberts would put up a strong scrap for second, and since the Triumph had a secure 3rd, which could be held easily, he didn’t press the issue. Behind Scott was Ron Pierce, and by the halfway point there were wide gaps between each of the first five places. Gary Fisher had also started the race on a worn front tire, and he couldn’t shake McLaughlin and Cliff Carr, the three of them running as if under a blanket.

By this time, Cal Rayborn had long since dropped out, after cutting some slow laps, when his arms “got tied up in knots” from his previous injuries. Dave Smith had been running behind Cliff Carr, but shortly after the halfway point, his chain went slithering across the last turn like a fast snake, and he looked down trying to figure out why the bike couldn’t get any power to the asphalt. He coasted into the pits, and did not reappear.

About the 25th lap, Steve McLaughlin got by Fisher, Carr aced a piston, to break up that threesome, and Steve got well ahead of Gary in short order. Pierce was out, too, and the order read Nixon, Roberts, Scott, McLaughlin, Fisher, Hurley Wilvert (Kawasaki’s “C” team), Geoff Perry, Jim Evans. By this time, about the 33rd lap, some of the riders were looking squirrelly, possibly due to tire problems. The only real scraps near the front were between Evans and Perry. Geoff got clear of Jim, and managed to pass Hurley for 5th, after Fisher dropped out on the 44th lap with a broken crank.

Nixon took the checkered flag with about a 25-sec. lead over Roberts; a cool and consistent race all the way. He popped a wheelie for his fans, and came around to pick up the flag for a parade lap. He grabbed the flag, and tried to accelerate; the bike sputtered and died. All of the ground straps between the engine and frame had melted. If they’re really running right, they’re supposed to blow at the checkered flag; Gary got just one lap beyond it. Irv Kanemoto said he could smell the epoxy during the teardown, but it had held.

McLaughlin was a jubilant 4th, Mert Lawwill held the Harley banner high in 11th. Dick Mann rode a consistent race to 9th, Aldana stayed on two wheels, and put the Norton in 12th, and lucky 13 was Kurt Liebmann on the BMW.

Perhaps appropriately, it was an all-eastern victory at this eastern race, and Kenny Robert’s victory over Nixon in the Econoline GP to the gate seemed somehow very hollow.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue