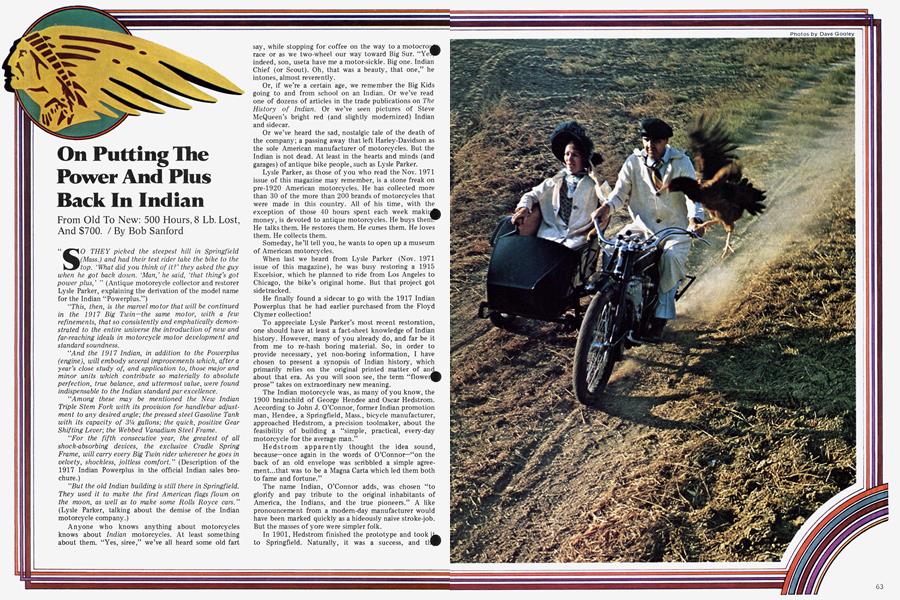

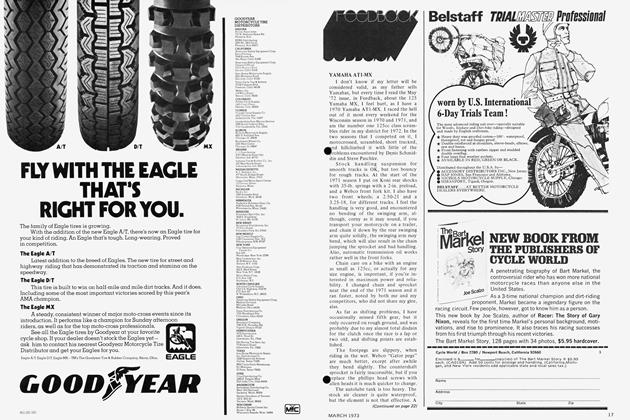

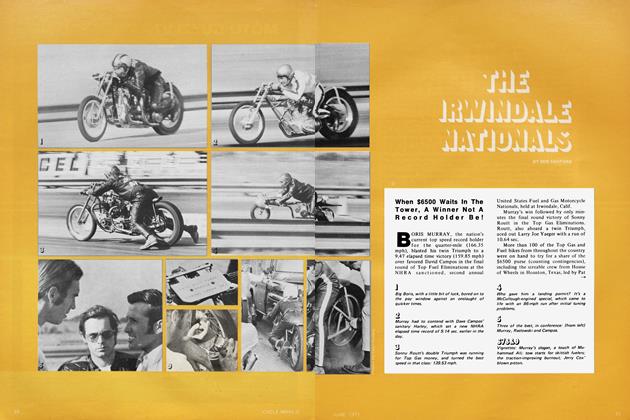

On Putting The Power And Plus Back In Indian

From Old To New: 500 Hours, 8 Lb. Lost, And $700.

Bob Sanford

SO THEY picked the steepest hill in Springfield (Mass.) and had their test rider take the bike to the top. 'What did you think of it?' they asked the guy when he got back down. 'Man,' he said, 'that thing's got power plus,' " (Antique motorcycle collector and restorer Lysle Parker, explaining the derivation of the model name for the Indian "Powerplus.")

“This, then, is the marvel motor that will be continued in the 1917 Big Twin—the same motor, with a few refinements, that so consistently and emphatically demonstrated to the entire universe the introduction of new and far-reaching ideals in motorcycle motor development and standard soundness.

“And the 1917 Indian, in addition to the Powerplus (engine), will embody several improvements which, after a year's close study of, and application to, those major and minor units which contribute so materially to absolute perfection, true balance, and uttermost value, were found indispensable to the Indian standard par excellence.

“Among these may be mentioned the New Indian Triple Stem Fork with its provision for handlebar adjustment to any desired angle; the pressed steel Gasoline Tank with its capacity of 3V4 gallons; the quick, positive Gear Shifting Lever; the Webbed Vanadium Steel Frame.

“For the fifth consecutive year, the greatest of all shock-absorbing devices, the exclusive Cradle Spring Frame, will carry every Big Twin rider wherever he goes in velvety, shockless, joltless comfort." (Description of the 1917 Indian Powerplus in the official Indian sales brochure.)

“But the old Indian building is still there in Springfield. They used it to make the first American flags flown on the moon, as well as to make some Rolls Royce cars." (Lysle Parker, talking about the demise of the Indian motorcycle company.)

Anyone who knows anything about motorcycles knows about Indian motorcycles. At least something about them. “Yes, siree,” we’ve all heard some old fart say, while stopping for coffee on the way to a motocross race or as we two-wheel our way toward Big Sur. “YeJ^ indeed, son, useta have me a motor-sickle. Big one. Indian Chief (or Scout). Oh, that was a beauty, that one,” he intones, almost reverently.

Or, if we’re a certain age, we remember the Big Kids going to and from school on an Indian. Or we’ve read one of dozens of articles in the trade publications on The History of Indian. Or we’ve seen pictures of Steve McQueen’s bright red (and slightly modernized) Indian and sidecar.

Or we’ve heard the sad, nostalgic tale of the death of the company; a passing away that left Harley-Davidson as the sole American manufacturer of motorcycles. But the Indian is not dead. At least in the hearts and minds (and garages) of antique bike people, such as Lysle Parker.

Lysle Parker, as those of you who read the Nov. 1971 issue of this magazine may remember, is a stone freak on pre-1920 American motorcycles. He has collected more than 30 of the more than 200 brands of motorcycles that were made in this country. All of his time, with the exception of those 40 hours spent each week makir^k money, is devoted to antique motorcycles. He buys then^^ He talks them. He restores them. He curses them. He loves them. He collects them.

Someday, he’ll tell you, he wants to open up a museum of American motorcycles.

When last we heard from Lysle Parker (Nov. 1971 issue of this magazine), he was busy restoring a 1915 Excelsior, which he planned to ride from Los Angeles to Chicago, the bike’s original home. But that project got sidetracked.

He finally found a sidecar to go with the 1917 Indian Powerplus that he had earlier purchased from the Floyd Clymer collection!

To appreciate Lysle Parker’s most recent restoration, one should have at least a fact-sheet knowledge of Indian history. However, many of you already do, and far be it from me to re-hash boring material. So, in order to provide necessary, yet non-boring information, I have chosen to present a synopsis of Indian history, which primarily relies on the original printed matter of and about that era. As you will soon see, the term “flowerj® prose” takes on extraordinary new meaning.

The Indian motorcycle was, as many of you know, the 1900 brainchild of George Hendee and Oscar Hedstrom. According to John J. O’Connor, former Indian promotion man, Hendee, a Springfield, Mass., bicycle manufacturer, approached Hedstrom, a precision toolmaker, about the feasibility of building a “simple, practical, every-day motorcycle for the average man.”

Hedstrom apparently thought the idea sound, because—once again in the words of O’Connor—“on the back of an old envelope was scribbled a simple agreement...that was to be a Magna Carta which led them both to fame and fortune.”

The name Indian, O’Connor adds, was chosen “to glorify and pay tribute to the original inhabitants of America, the Indians, and the true pioneers.” A like pronouncement from a modern-day manufacturer would have been marked quickly as a hideously naive stroke-job. But the masses of yore were simpler folk.

In 1901, Hedstrom finished the prototype and tooki^ to Springfield. Naturally, it was a success, and tl^P fledgling company produced three machines in its first year of operation. In 1902, it made 143 machines and production continued to soar until 1913, when the company reached its pre-1920 peak, selling 32,500 machines. For the most part, with the notable exception of the depression in the 1930s, business went well through the first half of the 20th century.

As is the case with many industrial companies, Indian dabbled in side ventures. At one time or another, Indian considered making automobiles ($50,000 in research) and airplane engines, and actually manufactured outboard motors, refrigerators and car shock absorbers.

Finally, because of a crucial research mistake in the late 1940s, which led the company to gear production toward lightweight machines (which Americans were not yet ready for), the Indian factory, for all intents and purposes, closed its doors in 1953.

But in and around the year 1917, Indian was the motorcycle throughout the world. Hendee and Hedstrom had been competition oriented since their days in the bicycle business. In fact, both had been professional bicycle racers, and Hendee had been the national high wheel champion for more than five years. So competition seemed a natural.

John J. O’Connor: “With a dual bicycle racing background, and a perfectly mated team of former racing stars, it was but natural that Hendee and Hedstrom recognized that the quickest and surest way to build a big and healthy market for Indian sales was to put it in competition and meet all comers.”

The results? O’Conner, again: “If there were any Indians entered you could bet, before you read the results, that Indian had cleaned the field.” In point of fact, apparently every early 20th century vehicle record worth setting (including the Trans-Continental record of 31 days, 12 hours and 15 minutes) and every race worth winning (including a 1-2-3 finish in the 1911 Isle of Man TT) was set or won on an Indian.

Although Indian engines through 1906 were manufactured by the Aurora Automatic Machinery Co., Aurora, 111., Oscar Hedstrom was given credit for the ingenuity of design and performance during the company’s first 15 years of existence. But Hedstrom temporarily left the company in 1913 and the Powerplus engine in 1916 was actually the result of someone else’s engineering. John J. O’Connor: “Many Indian dealers and more Indian riders were not at all pleased with the change, for, to them, Oscar Hedstrom was “Mr. Indian,” in all things mechan ical.”

But the Powerplus proved its power and plus, and, what’s more, Hedstrom returned to the Indian factory. O’Connor: “In July of that year (1916), Oscar Hedstron^ was wooed and won back to the Wigwam. Once more, thl^ famous team of Hendee and Hedstrom were pulling shoulder to shoulder. There was joy unconfined and the welkin rang with cheers across the land, when word of the return of the ‘Great Medicine Man’ fluttered on ‘talk leaves’ from the big Wigwam to all the tepees of the Great Indian Nation.”

But the shoulder to shoulder relationship didn’t last very long, as, again in O’Connor’s splendiferous prose, “Big Chief Hendee lay down the burdens of leadership and withdrew to a life of quiet relaxation and repose....”

O’Connor claims that Hendee’s retirement was planned, peaceful and voluntary. But there are certain things that indicate that this may not have been entirely the case. (It seems obvious, for instance, that the company had grown by leaps and bounds and, in 1916, there was “investment” money in the company that was more concerned with “growth” than motorcycles—i.e., a financier from N.Y., who apparently knew nothing about motorcycles, took over after Hendee’s departure.)

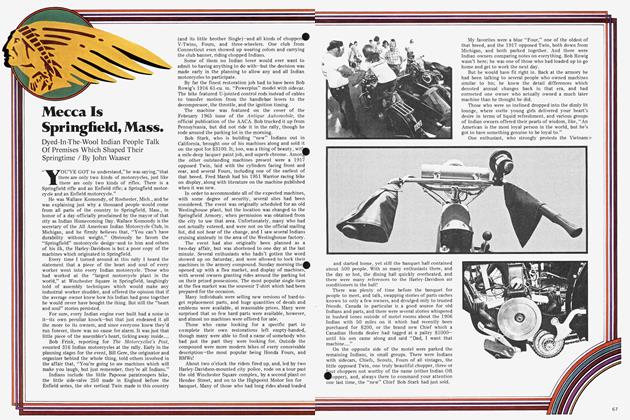

But whatever the case, Lysle Parker’s 1917 Indi^Ä Powerplus (with 1916 Indian sidecar) was manufacture^^ when Hendee was out and Hedstrom’s engineering capacity was probably only titular. The bike, though, Lysle Parker’s 1917 Powerplus, is an engineering feat that was remarkable for its time and was absolutely and categorically the evolutionary result of Hendee and Hedstrom’s enterprise.

Actually, there are more similarities than differences between the 1917 Indian Powerplus and today’s Superbikes. Of course, today’s bikes are bigger, stronger, faster and more reliable. But most of these advantages are the result of modifications, rather than radical changes in design and engineering concept.

The Powerplus has a twin-cylinder engine, with a displacement of 60.88 cu. in., which generates about 15 to 18 bhp. Power was transmitted to the rear wheel sprocket via a chain (as opposed to the belt driven models that were more prévalant during that era). The cylinders have a 3-1 /8-in. bore and a 3-31 /32-in. stroke. Its carburetion is essentially the same as today’s machines, and a magneto system provides ignition. Each piston ha^^ three rings and roller bearings were used for the con^ necting rods and mainshaft. A dry, multiple disc clutch was used in conjunction with the three-speed, handoperated transmission.

The bike has a wheelbase of 59 inches. A crude swinging arm arrangement functions as rear-end suspension. A fender mounted spring absorbed shock in the front; the principal behind which is not totally unlike today’s leading link systems.

Certainly, the Powerplus looked (looks) “funny” and awkward beside today’s street machines. But the engineering principals are essentially the same.

What’s more, you could buy a new Powerplus for $275.

“The first bike I ever owned was a 1917 Powerplus. In 1928 I paid $7 for a used one and spent $3 to charge the mag. ” (Lysle Parker, 1972.)

That particular bike disappeared a few decades ago, and it wasn’t until the late 1960s that Lysle Parker purchased his present Powerplus.

His latest 1917 Indian, with its tank full of holes, i^p tandlebars and rear brake assembly missing, its oxidized nd corroded parts, sat for nearly four years with the rest of Lysle Parker’s soon-to-be-worked-ons.

Then he found the sidecar.

“The influence of the sidecar is to be seen in both medium and heavyweight machines, for practically every owner of a motorcycle sooner or later attaches a sidecar. ” Motorcycling Manual, a hardcover, 256 page book published in England around 1914-15. (75 cents, Rose Bowl Swap Meet, 1971).

Parker’s sidecar, however, wasn’t in what you might call the best of condition. In fact, it wasn’t much more than a pile of rusted metal and rotted wood, and it took a very trained and discerning eye, indeed, to determine that Lysle Parker’s purchase was a sidecar, much less a 1916 Indian sidecar.

With the help of a friend, Bill Sommers, who is also a antique bike freak and happens to own a body and fender shop, Lysle Parker began to talk of restoring the sidecar. Working nights and weekends, they tore the thing apart, made patterns from the rusted sections and cut new pieces fcf sheet metal. As soon as they were reasonably well into the sidecar, Lysle Parker started on the bike. Handlebars were made, a brake assembly was found, rust was removed, parts were chromed, the engine was reconditioned. Then paint, paint, paint. Ten coats in all, plus primer (the color, incidentally, was matched to a wet sample that had come from the Indian factory).

Finally, after working some 500 hours, losing eight pounds and spending $700 for parts, services and materials, Lysle Parker completed the little blue beauty you see on these pages.

“The Indian, perhaps more than any other machine, is, well, totally American. And being the first motorcycle I ever owned, there was a soft spot in my heart for it, remembering all the spills and thrills. Naturally, this was the bike I had to look for, had to restore.

“The sidecar? Well, it's for the convenience of my wife and to compensate for the fact that I'm not quite as stable on two wheels as I used to be.

“And you know what I think? I think the name Indian is so imprinted in the minds of Americans that someday it'll be back; someday, someone will again manufacture Indian motorcycles. " (Lysle Parker, 1972.) 0