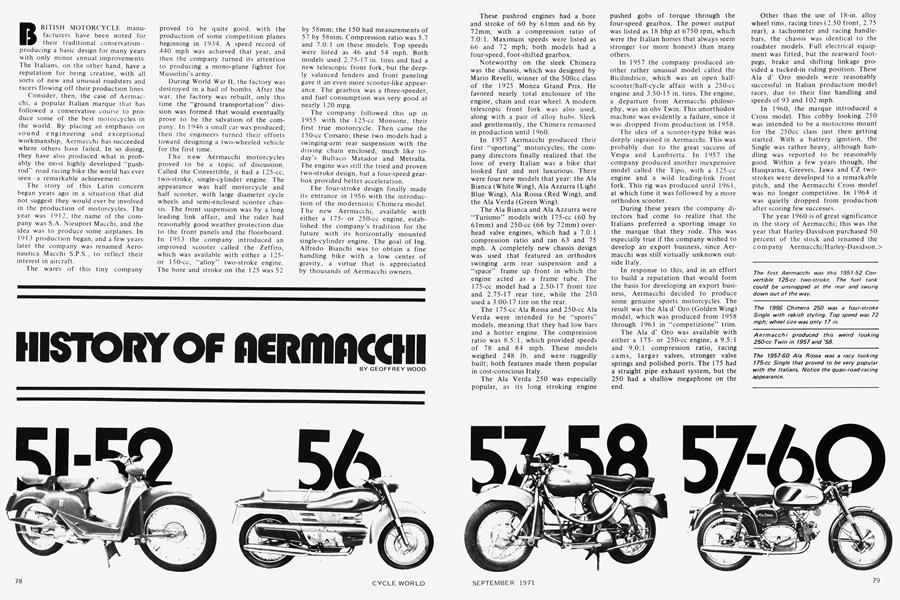

HISTORY OF AERMACCHI

GEOFFREY WOOD

BRITISH MOTORCYCLE manufacturers have been noted for their traditional conservatismproducing a basic design for many years with only minor annual improvements. The Italians, on the other hand, have a reputation for being creative, with all sorts of new and unusual roadsters and racers flowing off their production lines.

Consider, then, the case of Aermacchi, a popular Italian marque that has followed a conservative course to produce some of the best motorcycles in the w'orld. By placing an emphasis on sound engineering and exceptional workmanship, Aermacchi has succeeded where others have failed. In so doing, they have also produced what is probably the most highly developed “pushrod" road racing bike the world has ever seen-a remarkable achievement.

I he story of this Latin concern began years ago in a situation that did not suggest they would ever be involved in the production of motorcycles. Ihe year was 19 12, the name of the company was S.A. Nieuport Macchi, and the idea was to produce some airplanes. In 1913 production began, and a few years later the company was renamed Aeronáutica Macchi S.P.S., to reflect their interest in aircraft.

I he wares of this tiny company proved to be quite good, with the production of some competition planes beginning in 1934. A speed record of 440 mph was achieved that year, and then the company turned its attention to producing a mono-plane fighter for Mussolini’s army.

During World War II. the factory was destroyed in a hail of bombs. After the war, the factory was rebuilt, only this time the “ground transportation” division was formed that would eventually prove to be the salvation of the company. In 1946 a small car was produced; then the engineers turned their efforts toward designing a two-wheeled vehicle for the first time.

I he new Aermacchi motorcycles proved to be a topic of discussion. Called the Convertible, it had a 125-cc, two-stroke, single-cylinder engine. The appearance was half motorcycle and halt scooter, with large diameter cycle wheels and semi-enclosed scooter chassis. I he front suspension was by a long leading link affair, and the rider had reasonably good weather protection due to the front panels and the floorboard. In 1953 the company introduced an improved scooter called the Zeffiro, which was available with either a 125or 150-cc, “alloy" two-stroke engine. The bore and stroke on the 125 was 52 by 58mm; the 1 50 had measurements of 57 by 58mm. Compression ratio was 5.7 and 7.0: 1 on these models. Top speeds were listed as 46 and 54 mph. Both models used 2.75-17 in. tires and had a new telescopic front fork, but the deeply valanced fenders and front paneling gave it an even more scooter-like appearance. The gearbox was a three-speeder, and fuel consumption was very good at nearly 1 20 mpg.

The company followed this up in 1955 with the 125-cc Monsone, their first true motorcycle. Then came the 150-cc Corsaro; these two models had a swinging-arm rear suspension with the driving chain enclosed, much like today’s Bultaco Matador and Metralla.

I he engine was still the tried and proven two-stroke design, but a four-speed gearbox provided better acceleration.

The four-stroke design finally made its entrance in 1956 with the introduction of the modernistic Chimera model. The new Aermacchi, available with either a 175or 250-cc engine, established the company’s tradition for the future with its horizontally mounted single-cylinder engine. The goal of Ing. Alfredo Bianchi was to obtain a fine handling bike with a low center of gravity, a virtue that is appreciated by thousands of Aermacchi owners.

These pushrod engines had a bore and stroke of 60 by 61mm and 66 by 72mm, with a compression ratio of 7.0:1. Maximum speeds were listed as 66 and 72 mph; both models had a four-speed, foot-shifted gearbox.

Noteworthy on the sleek Chimera was the chassis, which was designed by Mario Revelli, winner of the 500cc class of the 1925 Monza Grand Prix. He favored nearly total enclosure of the engine, chain and rear wheel. A modern telescopic front fork was also used, along with a pair of alloy hubs. Sleek and gentlemanly, the Chimera remained in production until 1960.

In 1957 Aermacchi produced their first “sporting” motorcycles; the company directors finally realized that the love of every Italian was a bike that looked fast and not luxurious. There were four new models that year: the Ala Bianca (White Wing), Ala Azzurra (Light Blue Wing), Ala Rossa (Red Wing), and the Ala Verda (Green Wing).

The Ala Bianca and Ala Azzurra were “Turismo” models with 175-cc (60 by 61mm) and 250-cc (66 by 72mm) overhead valve engines, which had a 7.0: 1 compression ratio and ran 63 and 75 mph. A completely new chassis design was used that featured an orthodox swinging arm rear suspension and a “space” frame up front in which the engine acted as a frame tube. The 175-cc model had a 2.50-17 front tire and 2.75-17 rear tire, while the 250 used a 3.00-17 tire on the rear.

The 175-cc Ala Rossa and 250-cc Ala Verda were intended to be “sports” models, meaning that they had low bars and a hotter engine. The compression ratio was 8.5:1, which provided speeds of 78 and 84 mph. These models weighed 248 lb. and were ruggedly built; both features made them popular in cost-conscious Italy.

The Ala Verda 250 was especially popular, as its long stroking engine pushed gobs of torque through the four-speed gearbox. The power output was listed as 18 bhp at 6750 rpm, which were the Italian horses that always seem stronger (or more honest) than many others.

In 1957 the company produced another rather unusual model called the Bicilindrico, which was an open halfscooter/half-cycle affair with a 250-cc engine and 3.50-15 in. tires. The engine, a departure from Aermacchi philosophy, was an ohv Twin. This unorthodox machine was evidently a failure, since it was dropped from production in 1958.

The idea of a scooter-type bike was deeply ingrained in Aermacchi. This was probably due to the great success of Vespa and Lambretta. In 1957 the company produced another inexpensive model called the Tipo, with a 125-cc engine and a wild leading-link front fork. This rig was produced until 1961, at which time it was followed by a more orthodox scooter.

During these years the company directors had come to realize that the Italians preferred a sporting image to the marque that they rode. This was especially true if the company wished to develop an export business, since Aermacchi was still virtually unknown outside Italy.

In response to this, and in an effort to build a reputation that would form the basis for developing an export business, Aermacchi decided to produce some genuine sports motorcycles. The result was the Ala d’ Oro (Golden Wing) model, which was produced from 1958 through 1961 in “competizione” trim.

The Ala d’ Oro was available with either a 175or 250-cc engine, a 9.5:1 and 9.0:1 compression ratio, racing cams, larger valves, stronger valve springs and polished ports. The 175 had a straight pipe exhaust system, but the 250 had a shallow megaphone on the end.

Other than the use of 18-in. alloy wheel rims, racing tires ( 2.50 front, 2.75 rear), a tachometer and racing handlebars, the chassis was identical to the roadster models. Full electrical equipment was fitted, but the rearward footpegs, brake and shifting linkage provided a tucked-in riding position. These Ala d' Oro models were reasonably successful in Italian production model races, due to their fine handling and speeds of 93 and 102 mph.

In I960, the marque introduced a Cross model. This cobby looking 250 was intended to be a motocross mount for the 250cc class just then getting started. With a battery ignition, the Single was rather heavy, although handling was reported to be reasonably good. Within a few years though, the Husqvarna, Greeves, Jawa and CZ twostrokes were developed to a remarkable pitch, and the Aermacchi Cross model was no longer competitive. In 1964 it was quietly dropped from production after scoring few successes.

The year 1960 is of great significance in the story of Aermacchi; this was the year that Harley-Davidson purchased 50 percent of the stock and renamed the com pany Aermacchi/Harley-Davidson. >

This move was beneficial to each side: Aermacchi had been floundering financially in the brutally competitive Italian market, and the American company was witnessing a strong demand in their country for a smaller machine than their cumbersome V-Twins. The infusion of American capital allowed Aermacchi to develop a sizable export business, and Harley-Davidson acquired an obviously sound design that only needed some development and marketing to be a success.

The next Aermacchi, not at all surprisingly, was named the Wisconsin. This 250 was merely an improved Ala Verda model, but it became known for its reliability and fine handling. The Wisconsin, produced until 1967, introduced the American market to the sound design that H-D had acquired.

Meanwhile, the factory had produced a new scooter, one with small wheels and looking very much like a Lambretta. The Breeza had a 1 50-cc engine, and proved popular in Italy, if not in America. The scooter continued in the lineup until 1969, when the company finally lost interest in such things.

During the early 1960s the range continued with only minor changes until 1965, when a 50-cc moped was produced to meet the demand for an inexpensive utility model. The Zeffiretto was obviously not a smashing success, and was dropped from production after 1967.

During these years the Ala Verda had undergone a subtle but profound improvement, still retaining the four-speed box and long stroking engine. When imported into the U.S., the model was called the Sprint and featured a 2.4-gal. fuel tank and sports fenders. The idea was a street-scrambler approach, although the emphasis was on the “street” end of things.

The company also produced a warmed-over competition version for American racing called the Sprint CRS, which was set up for dirt track racing or scrambles events. The engine had a 27-mm carb, 10.0:1 compression ratio and racing cams, which enabled it to churn out 28 bhp at 8500 rpm. The 240-lb. CRS proved to be a terror on short dirt tracks, due mainly to its torque, traction and fine handling.

In 1967 the company introduced a vastly improved model called the Ala Blu (Dark Blue Wing), plus an improved Ala Verda model; both had a five-speed gearbox. The Ala Blu was a roadster, while the Ala Verda was the model we know as the Sprint.

The bore and stroke on these Singles was 66 by 72mm. Compression ratio was 8.5:1. The output was 18 bhp at 6750 rpm, providing a speed of 84 mph. The new five-speed box had ratios of 5.58, 6.58, 8.38, 11.17, and 16.26 to 1, which greatly improved acceleration.

In 1968 the company reentered the two-stroke field with a new 125-cc Single with a four-speed gearbox. The bore and stroke was 50 by 56mm, and 10 bhp was produced on a 7.3:1 compression ratio. This peppy lightweight, produced in both street and scrambles trim, had a speed of 60 mph.

Late in 1968 Aermacchi introduced another new model which quickly acquired a great reputation for its handling and performance. Called the GTS in Italy and the Sprint 350 in America, the new Single had a horizontal, 350-cc engine and four-speed gearbox with ratios of 6.25, 7.95, 1 1.0, and 18.18 to 1. Another model, the GT, is sold in Italy as a roadster with higher gear ratios and a larger fuel tank.

The bore and stroke of the 350 is 74 by 80mm; the output is 25 bhp at 7000 rpm. The engine, more noted for its wide spread of torque than its sheer horsepower and the 298 lb. weight, combined with a low center of gravity, provides a fine handling bike.

In 1969 the pace picked up at Varese with the introduction of a new 65-cc two-stroke and a 100-cc two-stroke, both of which are available in street or scrambles trim. There is even a genuine 1 00-cc motocross model, the Baja 100, which gives the H-D concern an exceptionally wide range of models to market in America.

Perhaps the most intriguing of the bunch is the Sprint ERS, a 350-cc ready-to-race model that took the trophy in the 1 969 Greenhorn 500-mile Enduro. The 259-lb. thumper is a fine handling bike on the track or in the woods, and its reliability is already legendary.

For 1971 the company fielded a range that included 65-, 100-and 175-cc two-strokes, as well as the 350 Single in both street and competition versions. This wide range enabled Aermacchi to develop a substantial export market in both Europe and America, which all proves that well engineered but conservatively designed motorcycles are still desired in this age of superbikes and exotic specials.

One of the most interesting aspects of the Aermacchi story is their achievements in the road racing game, which began in ernest after their merging with Harley in 1960. The first few years were wrought with blown engines, but their determination to succeed with a pushrod single-cylinder engine finally paid dividends with an enviable record.

As was previously mentioned, the first Ala d' Oro (racing) model was a production class racer complete with lights. Beginning in 1961, the Ala d’ Oro model was destined to be a pukka grand prix machine, even if it did have a pushrod engine.

The first true racing Ala d’ Oro was a 250-cc Single called the DS. It had the standard bore and stroke of 66 by 72mm, a compression ratio of 10.2:1, and it churned out 30 bhp at 9600-9800 rpm. The four-speed gearbox had a top gear ratio of 5.6:1, providing a speed of 124 mph with a fairing. Carb size was 30mm; weight was quite light at 230 lb.

This DS model was produced until 1964, at which time an improved DS-S model was introduced with a five-speed gearbox. The latest version also had its bore and stroke changed to 72 by 61mm, which allowed it to produce 33 bhp at 10,000-10,200 rpm. The top speed with fairing was listed as 129 mph, and acceleration was noticeably improved on the 11.0:1 compression ratio mount.

In 1963 the company also introduced a 350-cc Ala d’ Oro called the DS 350, with a bore and stroke of 74 by 80mm. This Single produced 33 bhp at 7800 rpm on a 10.5:1 compression ratio, and ran 127 mph on a 4.5:1 gear ratio. The gearbox had four speeds, and handling was exceptionally good.

During ihese years the results were often disappointing, due mainly to broken con-rods and valves. As the designers slowly worked out their failures, the works racers gradually began to gain some good placings in the international races.

In 1 962 the 250s gained 6th places in the Belgian and Ulster classics. In 1963 the 350 gained a 5th in the German GP and the 250 took several 6th places. In 1964 the record was no better, but in 1965 the 350 took 4th and 6th in the German GP, a 5th in the Finnish event, and 6th’s in Spain and France. The 250 gained 4th places in the Czech, Dutch, and German classics, plus 6th places in the Isle of Man and Italian events.

In 1966 the works 350 appeared with a five-speed gearbox; this, plus some added horses, made it a superb road racing machine. Renzo Pasolini finished a strong 3rd in the world championship that year, after many excellent places behind Giacomo Agostini’s MV Agusta Three. The company gained a few respectable places in the 250 class, but their interest was obviously shifting to the 350cc class.

In 1967 a new production five-speed 350 was introduced called the DS-S 350. This potent thumper churned out 38 bhp at 8500 revs for a speed of 136 mph. The compression ratio was 1 1.0:1, and a large 32-mm Dellorto carb was used. The Oldani front brake was replaced with a Ceriani four leading shoe binder on the works bikes, and a stronger frame provided improved handling.

In 1968 a new 250 was produced called the DS-S2, which turned over at 10,800 rpm and shoved out 35 bhp on an 11.0:1 compression ratio. 'Topspeed was listed as 133 mph. Dry weight was down to an almost unbelievable 210 lb. by then, which made the Single a hard bike to beat on a twisty course. Aermacchi horses are measured at the rear wheel, which is one reason why they go so fast on so little horsepower.

In 1967 the 350 gained many good places, but the spoils were divided between too many riders to obtain a good position in the championship. The 250 class by then was being ignored by the factory, since the fast two-strokes seemed to have the edge.

In 1968 the team came on strong, with Kel Carruthers finishing 3rd, Derek Woodman 6th, and Gilberto Milani and Brian Steenson tied for 7th position. The 250 was used only in local races that year.

The 350s used in 1968 were very much works specials, with a bore and stroke of 77 by 75mm, a huge 38-mm carb, an 11.75:1 compression ratio and an outside flywheel. The engine produced 42 bhp at the rear wheel, with 50 bhp (SAE) being produced at the crankshaft. This engine revs to 8800 rpm, and the fueled weight with fairing is very light at 248 lb.

In 1969 the marque did not fare so well, due mainly to a rash of injuries and many riders sharing in the “places.” In the Isle of Man TT, Kel Carruthers staggered the crowd by clocking a cool 131.4 mph in the speed trap set up at the Highlander, only 1.4 mph slower than the fastest Yamaha 350. In the race itself, Kel ran 2nd to Agostini until the last lap, when a battery failure put him out. Brian Steenson and Jack Findley finished 2nd and 3rd, trouncing the Yamahas rather decisively.

In 1970 the marque had a great year, with Alan Barnett finishing 2nd in the Junior TT at 98.16 mph after lapping at 99.32 mph. Alan beat the best 350-cc Yamahas by nearly 2 mph, and Aermacchi became the fastest 350-cc Single the Island has ever seen. Aermacchi’s speed trap figures give some indication of its fine handling: the fastest Aermacchi ran 136.4 and Barnett did only 134.3, while the best Yamaha was clocked at 141.7 mph. In the race itself, the Yamahas were no match for the pushrod Single.

(Continued on page 99)

Continued from page 81

In the continental races, the company fielded only a few riders, and then injuries depleted their ranks to virtually nothing. The works MV Agustas and Yamahas were obviously faster, but on a twisty course the modest little 3 50 Single could still put up a surprising show. Perhaps the most interesting item for the year was the new 408-cc model that Angelo Bergamonti rode in several events. The results were encouraging, and the factory hopes to develop a possible production racer.

In analyzing the record of the marque it is obvious that they have not made a genuine effort to win the championship. Their approach has been to test out their designs for obvious incorporation into a production racer and then on into standard roadster practice. The results may not be so spectacular, but the benefit to their customers is obvious. In the process, they have managed to keep the romantic old Single alive just a little longer, and they have produced some beautiful machines with a nostalgic intrigue all their own.

It is a well known fact that the race shop engineers have designed several ohc engines that really fly, but top management policy has prevented them from ever producing and racing these designs. The rumor has it that Milwaukee is the deterrent to this genuine effort at racing, which means that Aermacchi will have to be content with interesting but outclassed racing machines. The Singles will, no doubt, continue to be popular with private owners all over the world for their reliability, modest expense and fine handling.

On several occasions the company has indulged in some record attempts. One attempt, in I 956, was highly successful; Aermacchi still holds the onekilometer and one-mile marks in the 75-cc class. 1'he rider was Massimo Pasolini, father of Renzo, who used a streamlined two-stroke to clock 103.8 and 100.0 mph for the distances. Other than this, the company has not been fascinated by speed under the stopwatch.

Meanwhile, Aermacchi goes on its conservative way, racing when they feel the need to prove a design and producing some very good single-cylinder models for the man on the street. Colorful but not spectacular, they have made a significant contribution to the industry as well as the sport. Perhaps their greatest contribution is their proving that the Single is still a superb machine for all but high speed road racing, and that it has great durability.[o]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

SEPT 1971 1971 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

SEPT 1971 1971 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Dept

SEPT 1971 1971 By Jody Nicholas -

Departments

DepartmentsFeedback

SEPT 1971 1971 -

Technical, Etc.

Technical, Etc.Balancing the Mighty Multi

SEPT 1971 1971 By Gary Peters, Matt Coulson -

Features

FeaturesIt's A Steal

SEPT 1971 1971 By Joseph E. Bloggs