The Legend of the Gold Star

An Historical Tribute to a Great Single Cylinder Motorcycle

GEOFFREY WOOD

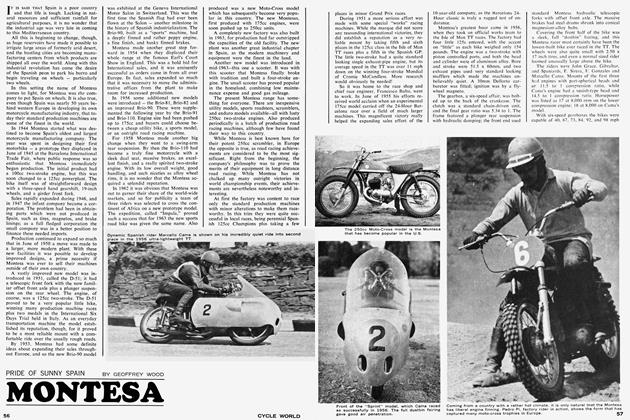

THE MOTORCYCLE IS by nature a rather sporting method of transportation, and it is only natural that afficionados of the game hold the sports type of machine in high esteem. One such thoroughbred is the BSA "Gold Star" — a 350 and 500cc single that has endeared itself to motorcyclists the world over.

The story of this fabulous British thumper is a tale that spans nearly 30 years, but its reign is sadly coming to an end, as the Gold Star has not been produced since 1963. With spare parts getting difficult to obtain, the illustrious single is slowly disappearing from the roads, tracks, motocross and cross-country circuits of the world. The Gold Star will soon live only in the pages of the history books.

Perhaps, then, it is fitting and proper to pause and pay tribute to this colorful machine before they are all gone from our view. For it is true, I suppose, that the Gold Star was the product of an era, and that era is coming to an end. From the 1930s through the 1950s, the single-cylinder motorbike was immensely popular and successful as a competition machine — both because of its reliability and its lower cost. Today the affluency of the world provides the means to afford the extra expense of a twin-cylinder model with its advantages of smoother power and greater revs, and so the big single is gradually fading from the scene.

The Gold Star, however, has amassed a record that is without equal in the whole saga of motorcycle sport, and it is doubtful if any modern-day machine will ever achieve such eminence. The record of this single includes victories in such diverse sports events as the Scottish Six Days Trial, World Motocross championship, Clubman's TT Racing, international road racing,British trials championship; American flat-track, cross-country, and road racing events, and many millions of miles all over the world as a road model in the hands of enthusiastic owners. That record must surely be the most versatile ever chalked up by a motorbike.

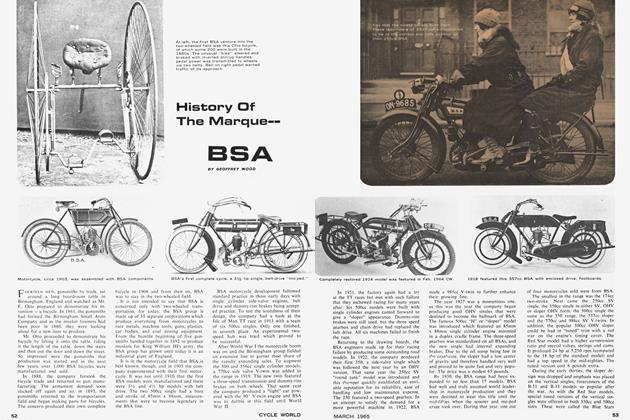

The story of the BSA single goes so far back that the pages of the history books are musty and yellowed. The books do tell us, though, that in 1927 the Birmingham concern produced a 500cc "H" model with a bore and stroke of 85 x 88mm — measurements that were to later feature in the story of the Gold Star. This new single was an 18-hp ohv model with a three-speed gearbox, and the engine was canted forward to give it a sloper appearance.

The more sporting minded riders of the day wanted a little more urge than the 65-mph "H" model, though, and so the marque produced a tuned version which had special valves, springs, cams, and a higher compression ratio piston. This model produced 24 hp at 5,250 rpm. With a speed of 85 mph, these thumpers were speedy mounts for their day, and the red star on the timing case was soon taken to be known as the "Red Star" model by enthusiastic owners.

During the early 1930s, the sloper model wafs dropped and new 350 and 500cc vertical singles were introduced that were the true ancestors of the Gold Star. The new singles could also be had in tuned trim with a blue star on the timing case, and these two "Blue Star" models had maximum speeds of 75 and 85 mph.

In 1935, the marque produced an improved single called the "Empire Star," and this design was available in 250, 350 and 500cc sizes. The Empire Star models were even quicker than their predecessor, and the dark green gas tank had a "star" emblem to denote that this was a very special machine for the discriminating owner. These BSAs were similar to the post-war B-31 and B-33 models that many "old timers" can remember, and they were popular with European riders.

During 1937, the story of the Gold Star got its really big boost when the factory prepared an Empire Star for a race at the famous Brooklands track. The Brooklands track was a large oval affair with high banked corners, and the speeds recorded were very fast for those days. One of the most coveted awards was the "Gold Star" given for lapping the track at over the 100 mph mark, and this was the goal that BSA was shooting for.

On June 30, 1937, the alcohol-burning single was fired up. Wal Handley was the rider, and he won a race at 102.27 mph and lapped at 107.57 mph, thus winning a "Gold Star." This success on the track led the BSA engineers to thinking about the racing game as well as about building a sports model. Consequently, they trudged back to their drawing boards to design the machine.

By early fall the new model was announced, and what a magnificent motorbike it was for 1938. The model was named the "Gold Star," which was only natural, considering the "Star" history and Wal Handley's winning of the Gold Star award at Brooklands. The philosophy was to produce a pushrod-operated overhead valve model that was less expensive than an overhead camshaft racing or sports model, and yet provide a performance that was competitive on either the road or race track. Another goal was to produce a versatile machine that could be used in many different types of competition with only minor changes of tires, cams and compression ratio, and the record books were destined to prove just how successful this philosophy would be!

The new Gold Star was available in either road, trials or track racing trim, and the model was probably the finest mount available for the sportsman who could only afford one machine, yet wished to race as well as ride every day on the road. The specifications of the Gold Star were interesting, and they were also rather advanced for those days.

The powerplant was a totally new design, and an alloy cylinder and head replaced the earlier cast-iron samples. The finning on the barrel and head were quite deep to aid in heat dissipation, and a higher compression ratio of 7.5:1 was used. The bore and stroke were 82 x 94mm, and the lowerend featured a rugged roller and ball bearing assembly.

Valve control was by double coil springs, and the engine breathed through a 1-5/32-inch Amal TT carburetor. Power output was listed as 30 hp at 5,500 to 5,800 rpm, which provided a speed of 90 to 95 mph with full road equipment. Ignition was provided by a magneto, and lubrication was by a gear-type pump from a four-pint tank.

The new engine was also accompanied by a completely new chassis. The frame was rigid with a girder front fork, and a four-speed gearbox with ratios of 4.8, 6.3, 9.9, and 14.3 was used. Tire sizes were 3.00-20-inch front and 3.25-19-inch rear, and powerful 7 x 1-3/8-inch brakes were featured. The dry weight was 350 pounds and the wheelbase was 54 inches.

In line with their new sporting philosophy, the BSA concern produced a competition model for trials or scrambles events. The engine was the same as the road model, but 2.75-21-inch front and 4.00-19-inch rear knobby tires made the bike suitable for dirt use. The model also featured an upswept exhaust pipe, narrow chromed fenders and chromed chain guards.

For the fellow who wanted to compete in road or track racing there was the "track" model, which had a higher compression ratio for petrol-benzol or alcohol fuel. A remote needle Amal racing carburetor with double floats was used, and a racing type seat was featured. The kickstarter was also removed, and a racing magneto was fitted. The exhaust system could be either a straight pipe, megaphone, or the large Brooklands silencer, and a buyer could order his bike without a front brake for Brooklands use.

In 1938, owners of Gold Star models competed with fair success in trials and local road races, but it was left for E. R. Evans to really seal the reputation of the single when he entered his 500cc model in the Ulster Grand Prix. By gearing his thumper about 4.2:1, Evans found he could clock something like 110 mph on the seven-mile long Clady Straight, which was a respectable speed for a push rod engine in those days. In the end he came home fifth at 79.04 mph, some 15 mph behind Jock West's supercharged BMW and five mph behind the fastest of the ohc Nortons. The pushrod BSA had lasted the

distance, which was something a lot of experts thought it would not do, and this all helped to establish the Gold Star as an exceptionally good design.

For the 1939 season, the Gold Star received only minor modifications aimed at cleaning up the design and making it more reliable. Roller bearings were adopted for both mainshafts, a five-pint oil tank with improved oil line routing was used, a better method of tappet adjustment was fitted, a larger fuel tank adopted, and a quickly detachable rear wheel was featured. The gear ratios that year were-more suitable for road racing or high-speed road use, with 4.8, 5.2, 8.15, and 11.8 being standard. The wider ratio gears were optionally available.

Then came World War II, and the production of the Gold Star came to a halt. After the war, there was such a great demand for transportation machines that the Gold Star was not put back into production until 1949, when a 350cc model was introduced. This new single was a completely redesigned model from the prewar Gold Stars, and it was followed in 1950 by a 500cc model.

The redesigned engines had alloy cylinders and heads, but the finning was not quite so generous as on the pre-war engine. The bore and stroke on the 350cc engine was 71 x 88mm, and the 500cc model was changed to 85 x 88mm. The rigid frame was also done away with and a new frame with a plunger rear suspension was used. The front fork was a telescopic type, and the gear ratios could be had in wide, standard, or close ratio sets.

These new engines turned over con-

siderably faster than the pre-war single, with the 350 model developing 24 hp at 7,000 rpm and the 500cc unit producing 33 hp at 6,500 rpm. Maximum speeds with muffler were about 95 to 100 mph for the 350 and 105 mph on the 500cc model. To cope with this increased performance the front brake was increased to eight inches in diameter, while tire sizes were 3.00-21-inch front and 3.50-19inch rear.

These road Gold Stars were soon followed by trials, scrambles and road racing versions. All of these had wheels, tires, cams, carburetors, frames and fuel tanks to suit the task at hand. The new singles were then exported all over the world, and motorsportsmen soon had them in the news.

The first great success was in the 1949 Junior Clubman's TT, when Harold Clark romped home first at 75.18 mph. This was followed with other Junior Clubman's TT wins in 1950 and 1951, and then John Draper scored many trials wins including the Scottish Six Days Trial in 1951. The works motocross team also did well, gaining many British and continental victories.

Meanwhile, the Gold Star was catching on fast in the United States, where it was destined to achieve perhaps its greatest victories. From cross-country events to road racing, the Gold Star proved its versatility, with such legendary greats as Aub LeBard and Nick Nicholson sweeping to victories in such classics as the Big Bear Run, Flintlock Enduro, the Catalina Grand Prix and many other west coast events.

Back at the factory, the design improvement work went on. In international motorcycle competition you can never sit still, or your rivals will soon have the better of you. The BSA engineers were fully cognizant of this, and the Gold Star underwent constant improvement. In 1952, new die-cast heads and cylinders were used, and the head had a bolted-on rocker box instead of the integral wells.

The 350cc engine was then modified by using a slightly different valve angle, larger valves and a larger carburetor. The connecting rod was also shortened 1/2 inch to reduce the engine height, as well as obtain a little greater crankshaft angularity, and both the 350 and 500cc engines had more finning for greater cooling.

These improvements helped keep the Gold Star at the front in many types of competition, and particularly so, in the 350cc class of European production model racing. The Gold Star won the 1952 Junior Clubman's TT in the Isle of Man, then followed this up with another victory in the 1953 event. In trials and motocross events the 500cc model scored many victories, such as Bill Nicholson's 1952 and 1953 British Trials Championships and J. C. Avery's 1953 British Scrambles Championship.

In America, the Gold Star became tremendously popular for all types of competition and Aub LeBard, Nick Nicholson and Chuck Minert continued their impressive showings in the rough-stuff events, while such greats as AI Gunter and Eugene Thiessen scored many victories on the flat tracks. Nicholson also displayed the versatility of both himself and his bike by trouncing the field in several of the first road races held ón the west coast.

Meanwhile, back at the factory, the engineers had been busy. For the 1952 International Six Days Trial, the competition department had prepared a special mount with a swinging-arm rear suspension. The bike performed so well that the company put the springer into production for the 1953 season. The new model featured a twin-tube cradle frame that was exceptionally rigid, and it provided improved stability at speed.

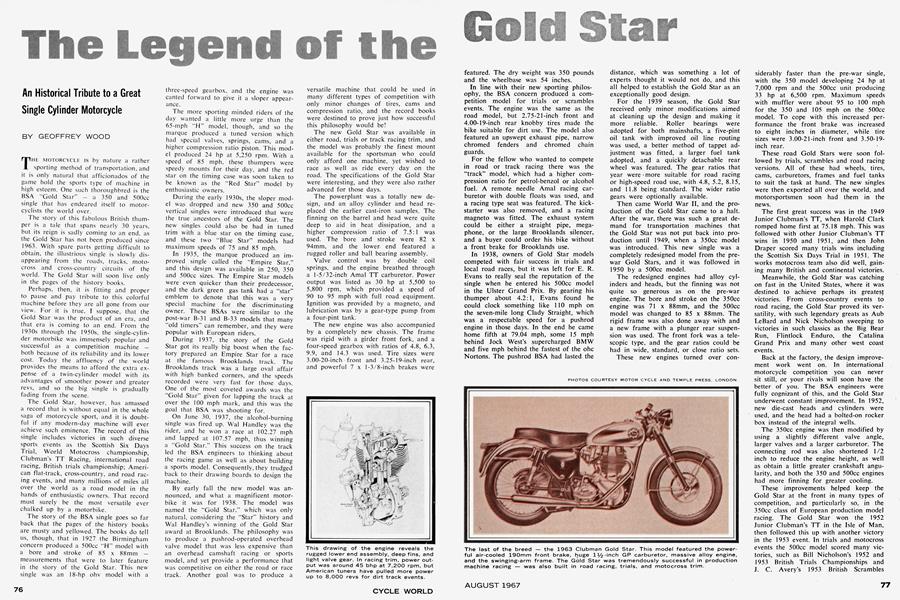

The following year, a completely redesigned engine was produced in both 350 and 500cc sizes, and history was to prove that here was the finest, most powerful pushrod single ever offered for sale. The most noticeable difference was the massively finned cylinder and head (manufactured by an aircraft casting company), but, internally, there were a great number of modifications that increased the performance as well as the reliability.

The bore and stroke remained the same, but the connecting rod was shortened for greater angularity to the crankshaft. This shortening of the rod necessitated an oval shape of the flywheels so the piston skirt would have clearance; but a few years later, the flywheels were round again and a shorter skirted piston was used. The rugged crankcases also contained a new En. 36 crankpin and a timed crankcase breather.

A great deal of attention was paid to the valve train in an effort to better control the valves at high engine speeds. The new engine was shorter, which shortened the length of the pushrods, and the heavy valve adjusters were done away with by using eccentrically mounted rocker arms to set the valve clearances. Stellited valve tips and a Nimonic 80 exhaust valve were also used.

These new engines were considerably more powerful than their predecessor, with 30 and 37 hp being wrung from the two powerplants. Amal GP carburetors were used, with the 500cc model having a large 1-7/32-inch size. In Clubman trim these new singles were very speedy road machines, with the 500cc model capable of about 110 mph and the 350 clocking a bit over the century mark.

The Gold Star was soon produced in trials, scrambles and road racing trim, with the scrambler being named the "Catalina," in honor of its great record in that historic American race. The various models all had tires, cams, pistons and fittings suited to the task at hand, with the scrambler and trials models having smaller 1-5/32-inch Monobloc carburetors. The Catalina model produced 37.8 hp at 7,000 rpm on an 8.8:1 compression ratio and straight pipe exhaust, which made it a mighty potent out-of-thecrate motocross machine.

During 1954, the Gold Star had a fabulous string of successes, with Jeff Smith winning the British Trials Championship and finishing third in the World Motocross Championship. The following year Jeff scored a great win in the classical Scottish Six Days Trial, and John Draper convincingly won the World Motocross title. Other BSA riders finished second, fourth and sixth in the motocross championship.

In America, the new Gold Star was catching on like wildfire. Tommy McDermott took a third in the 1954 Daytona Beach 200 Miler (the year that BSA made their fantastic first five-place sweep). Gold Stars in the hands of McDermott, Al Gunter, Warren Sherwood and Eugene Thiessen established a tremendous reputation during the middle and late 1950s, and race fans all over the country came to respect this BSA as a truly remarkable production model.

In European road racing, the Gold Star acquitted itself admirably. In the 1954 Clubman's Senior TT, Alistair King won at an average speed of 85.76 mph — which was a great testimony for a standard road model over the difficult TT course. Other riders of Gold Stars placed well in international road races, proving that a pushrod engine could put up a respectable performance against the exotic overhead camshaft machines.

Back at the factory, engineers made minor year-to-year changes in the Gold Star, the most notable being the increase in intake port size on the 500cc model to accommodate a huge 1-1/2-inch Amal GP carburetor. These modified engines were even more powerful, with the 500cc mount in road racing trim producing 45 hp at 7,200 rpm on a 9:1 compression ratio. The flat-out speed of the 500 was something like 120 to 125 mph with the megaphone, and 112 to 115 mph with the special "megaphone muffler" that was fitted to the Clubman model.

During the late 1950s, the factory produced a few pukka road racing models, although very few ever found their way to America. These grand prix models were truly beautiful bikes with their kneeknotched fuel tank, huge 190mm air-vane cooled front brake, and cobby looking seat. The brake was, however, put into production a few years later on the Clubman model, as well as some of the 650cc twins; then it was dropped in 1964 as being too expensive to produce.

The Gold Star, meanwhile, had not done so well in European racing. The famous Clubman's TT races were dropped after 1956, and motocross racing was taken over by Belgian and then Swedish machines that were much lighter than the ruggedly built Gold Star. In road racing, the overhead cam machines were also getting lighter and faster, and by the early 1960s the BSA was not a very competitive machine.

In America, tuners had succeeded in extracting even more power from the Gold Star, and by 1963, their performance was shattering. Possibly the greatest hour came in that year when Jody Nicholas won the Laconia 100 Mile race at record speed and Al Gunter won the Ascot race with Gold Stars taking the first three places. Nicholas, in particular, was impressive on the road racing courses (he had the big 190mm front brake), and the battles that he and Dick Mann waged must certainly be classics in the annals of American racing.

Unbeknown to enthusiasts the world over, a decision had been made at the factory to halt the production of the Gold Star. In November of 1963, the last models rolled off the production line, and an era had come to an end. This decision seemed strange to many, who felt that a redesigning to reduce the weight would have kept the model competitive. But despite its success in America, the single stayed dropped from production. This was a tough blow to the men who raced them so successfully, and one cannot help but wonder whether the advertising department or the engineers made the decision.

A good engine dies hard, though, and on both sides of the Atlantic, the deep bellow of the Gold Star's exhaust is still heard. In England, some mighty potent scramblers have been built using homebuilt frames, and in this country, the deeds of Sammy Tanner are the most noteworthy. Tanner continues to race his thumper in national championship flat track races with tremendous success, and his fourth Ascot National Championship last year must make the decision of the factory seem foolish to even the staunchest of vertical twin advocates.

Soon these last vestiges of glory will be gone, though, and the Gold Star will be just a legend in the minds of riders all over the world. While it lived it was great, and it must certainly be the most raceworthy pushrod single to ever grace the great race courses of the world. So far, no other single has come forth to take its place, and it is doubtful that one ever will. The most versatile model ever built in its trials, scrambles, road and racing trim, the BSA Gold Star may well be the end of a colorful and romantic era of single-cylinder motorcycle sport.