TRIUMPH HISTORY

GEOFFREY WOOD

THE TRIUMPH MOTORCYCLE, like many of its other British brothers, had its beginnings in the bicycle industry. Founded in 1885 in London, the early history of the Triumph Company is very nearly lost in the mists of time.

The founder of the company was, surprisingly, not an Englishman, but rather a German by the name of Siegfried Bettmann. Bettmann’s small bicycle manufacturing business prospered, and in 1887 he was joined by a fellow German, M. J. Shulte, who was a young design engineer. Together, these two Germans were later to have a profound effect on the infant motorcycle industry.

In 1888 the company moved to new quarters in Coventry, and in 1897 the brilliant Shulte was investigating the possibilities of a motor-powered bicycle. The motor-bicycle under examination was the Hildebrand and Wolfmuller, a German machine which Shulte regarded as being far too crude to ever be a workable design. The seeds of a motor-powered bicycle were sown in Shulte’s mind, though, and he was convinced that the future held great things for a motorbike.

It was in 1902 that the first motorcycle was produced by the burgeoning company, when a Belgian Minerva single-cylinder engine was mounted on one of their bicycles. The original 66mm bore by 70mm stroke engine had an automatic inlet valve, battery-coil ignition, and it was mounted below the front downtube of the bicycle. For 1903 the engine was modified to standard side-valve design, and in 1904 the Triumph had a British J.A. Prestwich engine which was similar to the Belgian Minerva powerplant. The factory also produced a model that year with a larger 3 hp Belgian-made Fafnir engine mounted centrally in the frame. All these early Triumphs had belt drive and bicycle pedalgear with a single rim-brake.

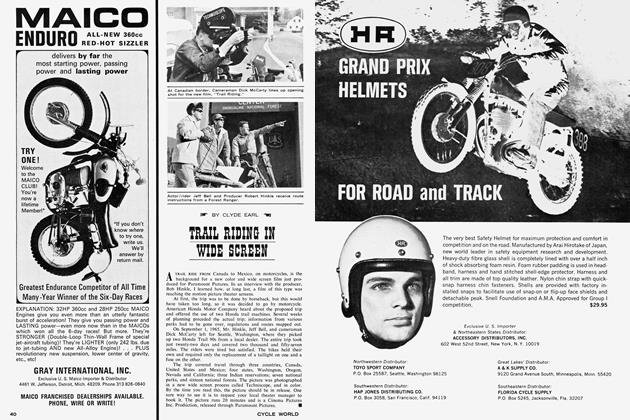

Despite the early enthusiasm for the motorbike, the public had found it lacking in reliability and overall performance. With this in mind, the brilliant Shulte designed the very first all-British motorcycle in 1904 and production began the following year. The engine was a 3 hp singlecylinder side-valve, centrally mounted in a properly designed motorcycle frame. Ignition was by ä reliable magneto, and the carburetor was of their own design.

To publicize this first all-British machine the company staged a demonstration run to prove its endurance. The goal was to cover 200 miles per day for six days — a really arduous test for machines of that era. The run was a success, and the new Triumph was on its way to tremendous popularity.

Production in 1905 was at the astounding rate of five machines per week, which rose to a healthy 500 machines for 1906. It was in 1906 that a front fork with a suspension spring was introduced, which made for a more comfortable ride. In 1907 the engine dimensions were enlarged to 82mm x 86mm and production increased to 1000 machines per year. In 1908 the engine was again increased to 85mm x 88mm, which made it a full 500cc; and in 1909 the production was up to 3000 units.

During those very early days Triumph became renowned on the race courses, and their trusty little singles achieved many victories. In the very first Isle of Man TT race, for instance, the marque garnered second and third places in the single-cylinder class. In 1908, Jack Marshall copped first place at 40.4 mph with a fastest lap at 42.48 mph. Other Triumphs took third, fourth and fifth places. The models featured direct belt drive at a ratio of 4.5 to 1.

A clutch in the rear hub was introduced in the 1911 models along with such niceties as adjustable tappets to set valve clearances. In 1913 a three-speed SturmeyArcher hub gear was available, and a 225cc two-stroke was also added to the range. The company experimented with a side-valve vertical-twin engine, too, but it never did reach the production stage. This last item was a hint of what was to come in later years.

For 1914 the bore and stroke dimensions were increased to 85mm by 97mm, making it a 547cc engine. For the sporting rider a 500cc model was still available, though, as the international racing regulations limited engines to that size. The reliable Triumph single continued to make its mark in competition, such as W. F. Newsome’s one-hour endurance record at 59.84 mph in 1910. The famous Isle of Man TT races continued to witness the reliability of the side-valve single as the marque garnered third in 1909, third and fourth in 1910, sixth in 1911 plus the onehour record at 63.11 by J. R. Haswell; second, fifth and sixth in 1912; and a fifth in 1914.

Then war settled over Europe and the factory became mobilized for military production. It was, in fact, in 1915 that the model H, which proved to be such a sound design, made its debut. The 547cc side-valve engine operated through a three-speed Sturmey-Archer countershaft gearbox with a final drive by belt. Altogether about 30,000 model Hs were built for the British Army.

After the war the model H was produced for civilian use, and this was superceded in 1920 by the S.D. — a model with all chain drive and a three-speed gearbox of their own manufacture. Then chief design engineer Shulte retired and Mr. Bettmann brought in Lt. Col. C. V. Holbrook, C.B.E., to replace him. The next model to come out of the factory was in 1924 when the 350cc model L. S. was introduced which had such advanced features as unit construction and full mechanical lubrication. Previously, the lubrication was provided by a hand or foot-operated oil pump.

During the early 1920s the British switched from side-valve engines to the overhead valve design, and Triumph was right to the forefront. In 1922 the factory entered a four-valve penthouse-head engine designed by Sir Henry Ricardo in the Senior TT, and Walter Brandish took second place with it. The model had a “castiron” engine with a bore and stroke of 85mm x 88mm, and it was one of the very first uses of the now popular slipper-skirt piston. The model also hoisted the classic hour record to 76.74 mph in the hands of Major H. B. Halford.

For 1923 the factory raced a two-valve 494cc single with measurements of 80.5 x 98mm and scored some significant victories. Probably the most noteworthy was Victor Horsman’s one-hour record of 86.52 mph. The following year he raised this to 88.21, and in May of 1925 he pushed it on up to 89.13 mph. Then he lost the record; and so in October he again made an attempt, raising the speed to 90.79 mph. This last mark was the first time a 500cc engine had pressed 90 miles into one hour. Then in 1926, Victor rode his faithful old single to a 94.15 mph mark, and that proved to be his swan-song.

During the middle 1920s the international racing scene was undergoing a great change. Previously, the machines were basically standard production models suitably prepared for racing, but by 1926 it had become, necessary to build a genuine racing machine if there was to be any chance of success. It was then, and still is, the policy of Triumph to race only what they sell; and so when it became evident that a “tuned” standard model had little chance of success, the interest in racing justifiably diminished. Tommy Simister did take the ohv single into a third place in the 1927 Senior TT, but other than that the name of Triumph faded away from the great racing courses.

All the knowledge gained from racing and record setting was not lost, though, and in the late thirties the company generally switched over to ohv engines. The 500cc Model P made its debut in 1925 at the modest price of 41 pounds 17 shillings (about $117) and 28,000 were produced the first year. A sporting edition called the model Q was also available in 1927, and a 277cc side-valve lightweight model W was produced.

In 1928 Triumph changed their historic grey with olive-green fuel tank colors to black with blue panels. In 1929 a 350cc ohv model was added to the range, and dry sump lubrication was adopted. In line with the general trend in the motorcycle industry, a shorter wheelbase tubular cradle-frame was used, and the fuel tank was the “saddle” type that hung over the top frame tubes instead of between them.

Then came the depression of the early 1930s and sales fell off. The whole range of Triumph machines was reorganized by A. A. Sykes and a small, cheap two-stroke was produced along with some big singles of “sloper” design. By 1934 the company was making great strides in its automobile manufacturing, and Val Page responded by designing new vertical singles of 250cc, 350cc and 500cc. A 650cc vertical twin was also produced which had even firing intervals with the pistons rising and falling together, unit construction, and a geared primary drive.

It was common knowledge by 1936 that the company was not doing well, though, and that their motorcycle production was going to be halted. Soon the Triumph would be a memory of the past — the only models visible would be preserved in the museums.

Just at that darkest hour a man by the name of J. Y. Sangster came forward to purchase the company, and the concern’s new name became the Triumph Engineering Co. Ltd. Sangster had previously been with the Ariel Company, and one of his first moves was to appoint Edward Turner as chief design engineer. Turner had done a great amount of design work on the Ariel Square Four and Red Hunter single - and these models had proved eminently successful. Would this be enough to save the Triumph?

The impact of the Turner genius on the new company was immediate and positive. A new range of single-cylinder machines was marketed in 1937 that acquired a reputation of being good looking, reliable and brisk performing. With these new thumpers, sales rapidly climbed and the future of the company was assured.

For the 1938 range another new model made its debut, and this machine can be said to have redesigned half of motorcycledom. Called the Speed Twin, the new 500cc model featured a very compact vertical twin engine with the pistons rising and falling together but firing alternately. With the addition of the twin to the range, Triumph had a mount for just about every use except racing.

The lowest priced were the 2H and 2HC models, which were 250cc ohv singles that developed 13 hp at 5,200 rpm. The compression ratio was 6.9 to 1, and the rigid frame bike weighed 310 pounds. Both of the lightweights were popular machines.

Next were the 350cc singles, two sidevalvers and one ohv model which developed 12 hp at 4,800 rpm and 17 hp at 5,200 rpm respectively. Then there were the Deluxe 5H and Deluxe 6S models in 500cc and 597cc. The 5H ohv model developed 23 hp at 5,000 rpm on a 5 to 1 compression ratio, and the 6S side-valve model produced 18 hp at 4,800 rpm. The measurements of the two engines were 84 x 89mm and 84 x 108mm. The 360-pound 6S model proved popular for sidecar use.

The pride of the range was, no doubt, the single-cylinder “Tiger” model. Produced in 250cc, 350cc and 500cc sizes, the Tiger models were “sports” machines which gave an improved performance over the standard machines. The Tiger 70 produced 16 hp at 5,800 rpm on a 7.7 to 1 compression ratio and weighed 310 pounds; the Tiger 80 developed 20 hp at 5,700 on a 7.5 ratio and weighed 320 pounds; and the Tiger 90 had 28.3 hp at 5,800 rpm on a 7.1 ratio and weighed 365 pounds. These were the 250, 350 and 500 respectively.

The star of the Tiger range was the 500cc model, and it had husky 7" x 1-1/8" brakes, narrow fenders, a 20" x 3" front tire, and a 19" x 3.50" rear tire. All the Tiger models could be ordered in competition trim, which made them suitable for trials or scrambles use. Optional extras included an upswept exhaust pipe, knobby tires, a wide ratio gearbox with ratios of 4.78, 6.93, 11.00, and 14.7 to 1, quickly detachable lights and rear wheel, and individually assembled and tuned engines. As on all Triumphs the frame was rigid and the front fork was of a girder type. The Tigers were altogether a fine mount for the sportsman, and all this at the modest price of 77 pounds ($385).

Then, of course, there was the new Speed Twin which had measurements of 63 x 80mm and produced 28.5 hp at 6000 rpm on a 7 to 1 compression ratio. The twin weighed 365 pounds, had a 54" wheelbase and sold for 75 pounds ($375).

This new range of Triumph machines proved very popular, and the sales of the company continued to expand. The sports singles won their share of the trials and scrambles events, and the Speed Twin set an all-time Brooklands 500cc lap record at 118.02 mph. The twin was built and ridden by I. B. Wickstead, and the model featured a supercharged engine. Another Brooklands all-time lap record was also garnered by Triumph, this one in 1939 by W. F. S. Clarke at 105.97 mph on his 350cc fuel burning single.

For 1939 the range of machines and optional parts offered stayed the same as for 1938 except that an exciting new Tiger» 100 replaced the Tiger 90 model. Based upon the Speed Twin, the new Tiger 100 was a mount to satisfy the most discriminating buyer in 1939. The engine was individually built, tuned, and tested on a dynamometer; and it was certified to produce 33 to 34 hp at 7,000 rpm on a 7.75 to 1 compression ratio. Each owner received an actual dynamometer report with his engine, signed by the works test mechanic.

The rest of the specifications whetted the appetite of the motorcycle connoisseur. The mufflers were designed to be megaphones with end caps, and by removing these caps an owner was ready to race. The front wheel had a 3.00" x 20" ribbed tire, and the rear wheel had a 3.50" x 19" semi-racing tire. The front brake drum was ribbed for extra cooling, and both brakes were 7" x 1-1/8" in size. A special bronze head was optionally available for the Tiger 100 which gave improved heat dissipation, and a set of tuned straight pipes were also available. With a top gear ratio of 5.0 to 1, the 7000 revs with the open megaphones gave a top speed of 106 mph. Truly, this was the machine that the British motorsportsman had dreamed of.

Then came the second war, and on a dark November night the factory was left a pile of twisted beams and smoldering rubble. To this day no one knows quite how it was done, but in ten months a new factory was built at a new location in Allesley, near Meriden. And there during the war, Triumph produced a 350cc ohv single for military use.

When peace returned Triumph immediately resumed production, and a new range of machines was fielded. Gone were the single-cylinder models, and Triumph began production of twins exclusively. A new telescopic front fork replaced the old girder fork, and in 1947 the Triumph “Spring Hub” made its debut. This Spring Hub was a rather unique method of rear suspension as it contained the coil springs within the large rear hub.

A new 350cc twin was also added to the range to supplement the Speed Twin and Tiger 100 models. In deference to the limited amount of cash available in those immediate post-war years, the Tiger 100 was not quite so sporting a mount as in the pre-war days. Horsepower was down from 34 at 7000 to 30 at 6,500 rpm, and all the hand assembled and dynamometer tested qualities were gone. The brakes were not finned, no megaphone mufflers were fitted, and few of the pre-war optional “goodies” were available.

The basic design was still very good, though, and quite naturally some sportingminded riders turned their attention to tuning the Tiger 100 for racing. Many racing men recognized that a small-bore twin had a great advantage over a big-bore single as far as getting the highest possible compression ratio on the dreadful 72 octane “pool” petrol that was used.

It was Ernie Lyons, the Irish farmerracer, who got the show on the road. Working with factory support, Lyons took a standard Tiger 100 and began building his racer. During the war Triumph had made an electrical generating power-unit for Lancaster bombers using a standard 500cc twin engine which had an alloy head and cylinder with fan cooling. Ernie borrowed this alloy head and cylinder part and also obtained the experimental Spring Hub to use. With just the normal amount of speed tuning for the day, Ernie was ready to compete.

The first event for the racing Tiger was the 1946 Ulster Grand Prix. All sorts of problems were encountered that day, but the bike did show some dazzling, if rather spotty, performance. Nevertheless, Lyons was encouraged and he set about to cure all the “bugs.” In September he and his Tiger appeared again, this time at the Manx Grand Prix for amateurs held over the famous Isle of Man TT course. All went well that day, despite the appalling rain, and Ernie romped home the winner at 76.73 mph.

About that time the folks at Meriden began to give some serious thought to this racing game, and so for the 1947 season a prototype racer was prepared for the Grand Prix racing season. The late David Whitworth, a top-flight racing man, was engaged to ride; and he spent the summer touring the continental events. Whitworth had a highly successful season, too, winning minor Grand Prix events at the Circuits de La Cote, du Limbourg, and George Truffant. David also captured a third place in the Dutch Grand Prix, beaten only by the factory Norton of Artie Bell and the Güera “Saturno” single of O. Clemencich. Encouraged by these successes, in late 1947 the factory announced that a production road racing model would be marketed for the 1948 season. Called the “Grand Prix,” the racer incorporated all the knowledge that had been gained during Whitworth’s campaign. The idea was certainly not to build the best racing machine available, but rather to use as many existing standard parts as was possible in an effort to keep the price down. In this manner a beginner could have a pukka racer at a price well below that of an overhead camshaft racer, and yet still have a speedy and reliable mount.

(Continued on page 112)

cont.

The new Grand Prix model was a beautiful machine, and it was fast. The engine was a 500cc twin with standard bore and stroke of 63 x 80mm, and an alloy cylinder and head were fitted. Megaphone exhausts were used, the standard frame had the rear spring hub, and both brakes were a massive 8" x 1-3/8". The wheel rims and fenders were of light alloy, with a 3.00" x 20" ribbed racing front tire and a 3.50" x 19" studded racing rear tire.

Each engine was mirror-polished throughout, and the cams were designed to give a great amount of torque over a wide rpm range. Two Amal carburetors were used, and the float bowl was remote mounted. The engines were all hand assembled and tested on a dynamometer. On a 10.5 to 1 compression ratio the horsepower was 42 at 6800 rpm. Top gear of the four-speed close-ratio box was 4.57 to 1, and at 6800 revs this provided a maximum speed of 112 mph. On any downhill run the revs could safely soar to 7400 rpm, which gave a speed in excess of 120 mph. Another good point in the GP model’s favor was its 314-lb. weight, which was well below the 370-lb. weight of a Norton Manx model.

So enthused were the Triumph folk over the new racer that they decided to set aside their policy of no direct participation in racing. In short, they fielded a genuine works team mounted on some GPs that received that little extra bit of tuning and bearing work that always helps. They also hired some of the finest riders available with such famous former TT course winners in the lineup as Bob Foster, Fred Frith and Ken Bills.

Altogether a total of nine Grand Prix Triumphs were entered in the Senior TT — but then followed a tale of disaster. One by one the riders fell by the wayside — gas tanks fractured, gearboxes disintegrated, clutches failed and engines blew. In the end, not one GP model finished. Shaken but not yet defeated, the designers went back to the race shop and produced a new fuel tank and made minor changes in the other engine and transmission parts that had failed.

On the continent the small improvements revealed at last the excellence of the basic design. In the Dutch Grand Prix, David Whitworth took fourth; in the Ulster, Bill Beevers took fifth; and in the fast Belgian event, Foster, Whitworth and Bills took a magnificent fourth-fifth-sixth. Then, in September, Don Crossley won the Manx Grand Prix for amateurs in the I.O.M. at a post-war record speed of 80.63.

Despite the late season successes, the memory of the embarrassing Isle of Man episode brought the decision not to participate in racing anymore. The factory did produce the GP model for one more year, though, and many loyal privateers carried on with their twins. In the 1949 Senior TT they had a truly great hour, too, with Sid Jensen of New Zealand and C. A. Stevens taking fifth and sixth places, the former at 86.928 mph. These two Triumphs were the first non-works bikes to finish — a really magnificent achievement.

But then Triumph faded away from the racing scene and concentrated instead on improving their standard production machines. In 1950 the now famous Thunderbird model made its debut with a husky 650cc engine that had measurements of 71mm x 82mm. Then there followed the alloy-engined Tiger 100 and Trophy models, the latter establishing a great reputation in the trials world. It was the Thunderbird that once again set a trend, though, just as the original Speed. Twin did in 1937. With its beefy power it has proven exceptionally popular all over the world, and particularly so in the U.S.

Never ones to sit on their laurels, the design improvement work went steadily on. In 1954 a new swinging arm frame made its debut, and also a snarling 42 hp model called the Tiger 110. Then there was the 150cc Terrier single, a light and inexpensive mount that was later developed into a 200cc model. Then, in 1957, came the new 21 cubic inch model that featured comprehensive enclosure and provided a “gentleman’s” machine.

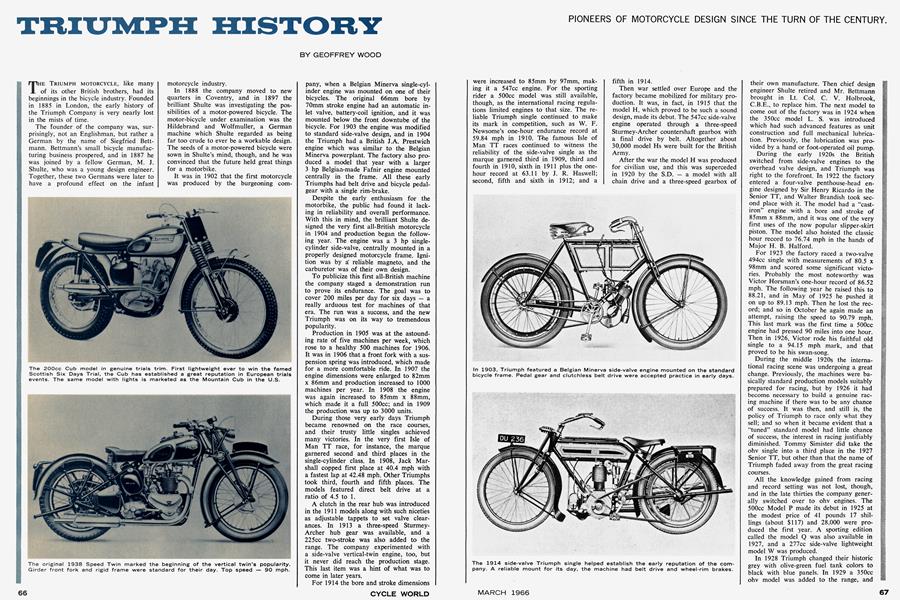

Today the Triumph range is even greater. The 200cc Cub can be had in road or genuine trials trim, this latter bike being the first lightweight to ever win the famed Scottish Six Days Trial when Roy Peplow did the trick in 1959. Based on the popular trials model, the Mountain Cub is built especially for the U.S. market and features lighting equipment and a 3.00" x 19" front tire instead of the 2.75" x 21" size.

Then there are the two “short-stroke” 500cc models with bore and stroke of 69 x 65.5mm, one in a street trim and the other in sports attire. If it’s power you want there are the 650cc models, the standard Thunderbird and the potent Bonneville. The Bonneville is one of the fastest machines going today, and this twin-carburetored bomb has many victories to its credit in long distance European production-machine racing.

Produced especially for the U.S. market also, the TR-6 and TT Bonneville models are competition mounts for cross-country and TT racing. Their record in U.S. competition events is so great that it suffices to state that they simply dominate these two sports. The 350cc twin and the new scooter round out the range, although these models are vastly more popular in Europe than in the U.S.

And so this is the story of Triumph — a story of progress and achievement. Even today they are not sitting still, though, as stories keep filtering out of England about a three-cylinder 750cc model and an overhead cam 250cc Cub. One can just not imagine Triumph taking a back seat to anyone — history teaches us differently.