RICKMAN MICRO 125 METISSE

CYCLE WORLD IMPRESSION

Expensive... A Tiger ... A Handler ... But Not For Leisure World Types

IF THE RICKMAN BROTHERS will be remembered in motorcycling, it will be for the salvation of the big bore dirt machine. Vive la Triumph, vive-la Bay-Ess-Ah, vive la Matchless. Le quatre-temps est mort, vive la Metisse!

By doing what the majority of major manufacturers failed to do—i.e., building decent handling scrambles frames for their thumpers and twins—they started a whole new trend in America and overseas and kept four-stroke lovers deliriously happy.

Now the Rickmans have crossed over the bridge. They are making a MicroMetisse. And anything micro these days is bound to be a ring-ding. Horrors.

But the move to the lightweight category isn’t a total cop-out, really, for the big Métissés will continue on. The Micro is merely a rightful attempt by the brothers to cash in on growing public pressure for specialized, all-business small-bore racing machinery.

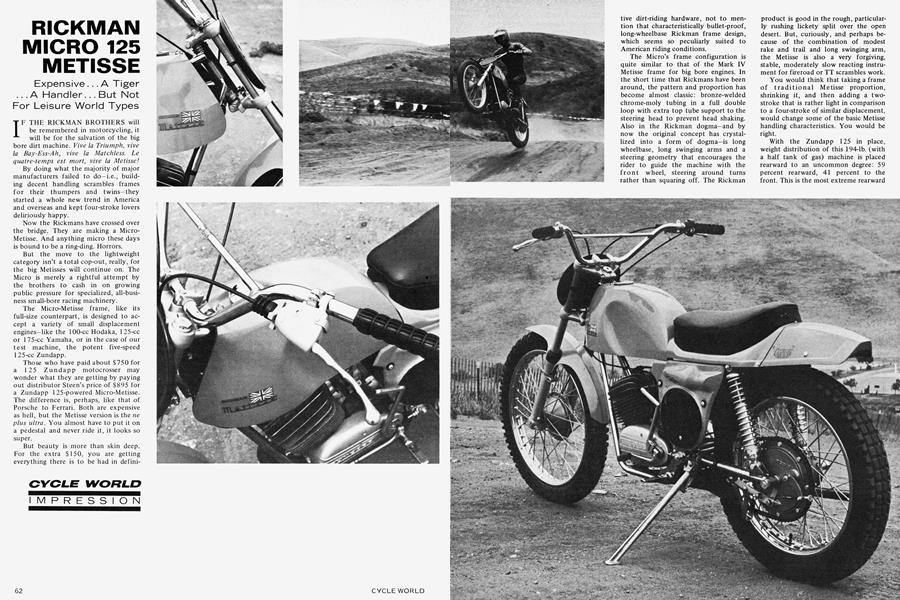

The Micro-Metisse frame, like its full-size counterpart, is designed to accept a variety of small displacement engines—like the 100-cc Hodaka, 125-cc or 175-cc Yamaha, or in the case of our test machine, the potent five-speed 125-cc Zundapp.

Those who have paid about $750 for a 125 Zundapp motocrosser may wonder what they are getting by paying out distributor Steen’s price of $895 for a Zundapp 125-powered Micro-Metisse. The difference is, perhaps, like that of Porsche to Ferrari. Both are expensive as hell, but the Metisse version is the ne plus ultra. You almost have to put it on a pedestal and never ride it, it looks so super.

But beauty is more than skin deep. For the extra $150, you are getting everything there is to be had in definitive dirt-riding hardware, not to mention that characteristically bullet-proof, long-wheelbase Rickman frame design, which seems so peculiarly suited to American riding conditions.

The Micro’s frame configuration is quite similar to that of the Mark IV Metisse frame for big bore engines. In the short time that Rickmans have been around, the pattern and proportion has become almost classic: bronze-welded chrome-moly tubing in a full double loop with extra top tube support to the steering head to prevent head shaking. Also in the Rickman dogma—and by now the original concept has crystallized into a form of dogma—is long wheelbase, long swinging arms and a steering geometry that encourages the rider to guide the machine with the front wheel, steering around turns rather than squaring off. The Rickman

product is good in the rough, particularly rushing lickety split over the open desert. But, curiously, and perhaps because of the combination of modest rake and trail and long swinging arm, the Metisse is also a very forgiving, stable, moderately slow reacting instrument for fireroad or TT scrambles work.

You would think that taking a frame of traditional Metisse proportion, shrinking it, and then adding a twostroke that is rather light in comparison to a four-stroke of similar displacement, would change some of the basic Metisse handling characteristics. You would be right.

With the Zundapp 125 in place, weight distribution of this 194-lb. (with a half tank of gas) machine is placed rearward to an uncommon degree: 59 percent rearward, 41 percent to the front. This is the most extreme rearward bias we have measured. By way of comparison, a 250 CZ shows a distribution of 52.5/47.5 percent, rearto front. Practically speaking, the rearward weight bias of the Micro is hair-raising until you get used to placing your weight properly forward when you apply throttle. However, it is not all bad, for high performance 125 scrambles engines such as the Zundapp must turn at high rpm to extract the usable power from them. As high rpm operation tends to result in wheelspin, extreme rearward bias helps get some of that horsepower to the ground.

As the Micro’s wheelbase (53.0 in.) is about 2 to 3 in. longer than usual for a 125, the moment is increased. So front wheel aviation is decidedly easy, but always seems to stop a tad short of disaster. Thus the Micro differs from its bigger brothers, Mark III and IV, both of which never felt light in the front end. But there is still a similarity produced by the long swinging arm and quick front end; the Micro powerslides nicely if the rider neutralizes the rearward weight bias by getting his own weight forward.

Taking into account the Micro’s lighter powerplant and overall weight, the Rickmans have been able to simplify construction of the frame somewhat. For instance, junction of top and front tubes to the steering head is quite straightforward—front tubes to the bottom of the head, top tubes to the top—rather than involving the sexy crossover and bending of the toptubes around the downtubes found in the big chassis. The frame tubing itself is smaller—of .875 in. o.d.

If you thought that the original Rickman method of adjusting rear chain tension was unique, then the latest innovation must take the cake! On the original big bore chassis, the chain could be tightened, not by the usual method of moving the rear axle, but by swapping differently drilled coin-shaped inserts to move the swinging arm pivot rearward. On the Micro, tension is still regulated by moving the swinging arm pivot, but the use of inserts is eliminated.

Instead, the swinging arm is pivoted from slotted plates welded on the frame cradle, and, after the pivot bolts are loosened, they are positioned with the small bolt and locking nut arrangement used in conventional rear axle adjustment systems.

It’s quick. It’s simple. But because the pivot mounting plates are mounted on the convex side of the bend in the cradle tubing, it also looks a bit frail. But there are three factors that work in its defense. The plates are thick, for one thing. And the engines for this frame are not big, thumping four-bangers, with metal-wrenching torque impulses. Finally, potential distortion of the plate-toframe weld on the convex side of the cradle is reduced by extending a portion of the plate and welding it to the inside of the cradle where it also serves as a mounting for the footpegs.

If the swinging arm twitched, we couldn’t tell, and the new system— which the Rickmans say has been tested in hundreds of hours of competitionshould be adequately strong. But pay attention to the tightness of the swinging arm pivot bolts, just in case.

The rest of the Micro 125 chassis features all the latest superb goodies: Ceriani C-4000 forks and A-2000 rear spring/damper units, and lightweight Rickman conical hubs. Suspension travel is 6 in. front and almost 3 in. rear. Contributing to the machine’s toughness are steel rims (18 in. rear, 21 in. front) with heavy gauge spokes. The fiberglass tank (1.7 gal. or optional 2.5 gal.), fenders and side panels come in a light U.S. Racing Blue; they are tough, as well as being extremely attractive and free of blemishes.

Our sole objection with the rolling gear has to do with those fancy goldenhued brake units, which seem to require an inordinate amount of pressure to actuate. For all that dough, we expect things to work properly right off. Use of a trials-pattern rear tire instead of a motocross knobby also puzzles us.

For those unfamiliar with the Zundapp 125-cc motocross engine, it would be appropriate to note that it is an absolute tiger and not the sort of thing to please the casual cowtrailer. The claimed 15 bhp from this 54 by 54-mm piston port Single is quite an honest figure. Keep it up on the power band and you get performance akin to some 250-cc engines. Let it slip off the power band, and you know right off it isn’t a 250. You don’t torque your way up hills; you blast. But the ZundappMetisse combination is meant for racing, very competitive racing, in fact, not for Leisure World activities in the desert sun.

Spread of the gearbox ratios suits the engine characteristics perfectly, and the optimum part of the power band is always available at a flick of the lefthand one-down-four-up shift lever. But a careless rider will find himself annoyed by the easy availability of false neutrals when upshifting to the intermediate gears. If he uses the clutch he must shift deliberately, or, better yet, avoid using the clutch at all. There is no such problem when downshifting.

All in all, the Micro is superb. Nine hundred dollars is a great bundle of money for a one-two-five, but if that is what it takes to win, there will be no shortage of Americans willing to pay the price for glory in this growing class.

Even as a playbike, the Micro 125 Metisse—which is sold for the quoted price completely assembled and ready to go—will endear itself to those who like to own the hairiest of esotérica.

After all, who would have ever believed that Rickman’s frame kits for big bores, costing the fantastic prices that they do, would have ever caught on? When they did, it was like the exotic sports car boom all over again. There’s no accounting for American flamboyance and preference for the very best, [o]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

September 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1970 -

Departments

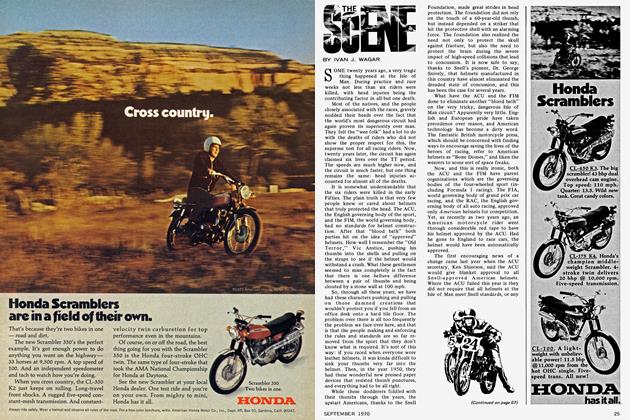

DepartmentsThe Scene

September 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

September 1970 -

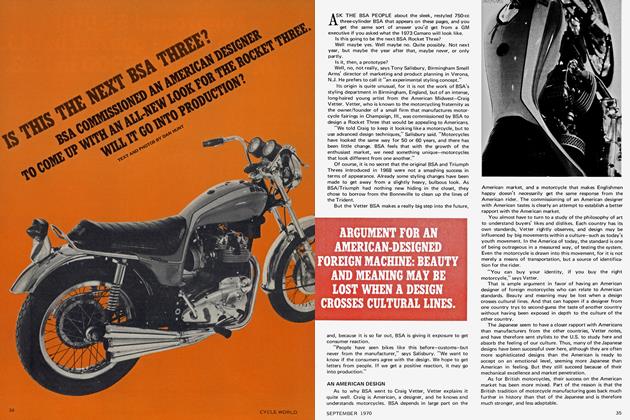

Special Feature

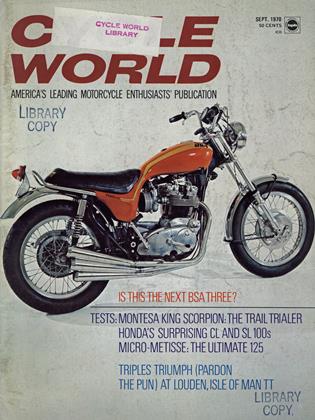

Special FeatureIs This the Next Bsa Three?

September 1970 By Dan Hunt -

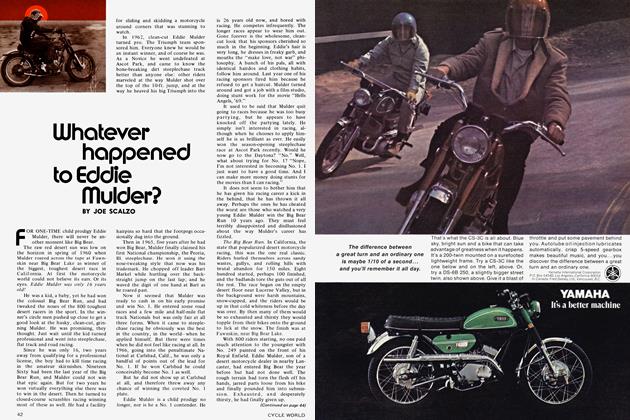

Features

FeaturesWhatever Happened To Eddie Mulder?

September 1970 By Joe Scalzo