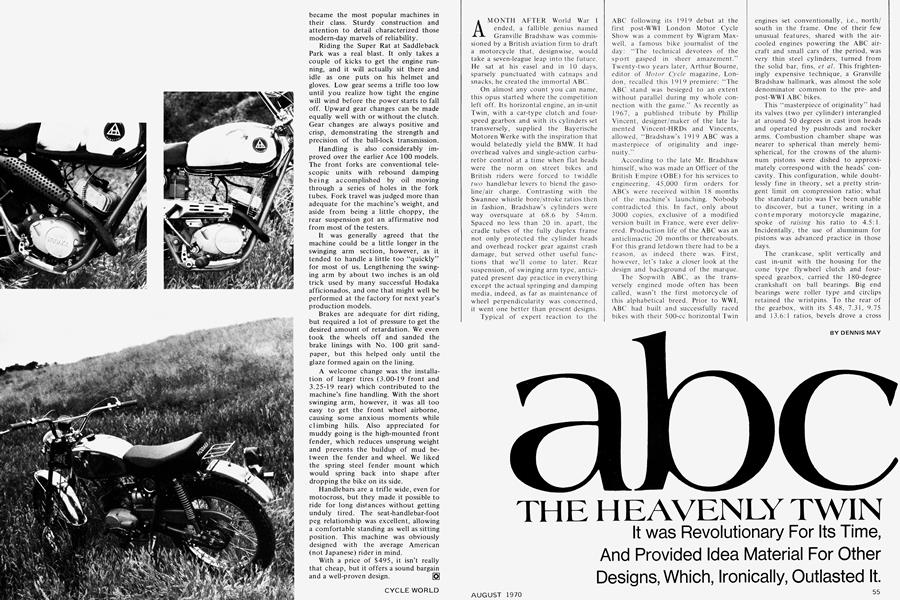

abc THE HEAVENLY TWIN

It was Revolutionary For Its Time, And Provided Idea Material For Other Designs, Which, Ironically, Outlasted It.

DENNIS MAY

A MONTH AFTER World War I ended, a fallible genius named Granville Bradshaw was commissioned by a British aviation firm to draft a motorcycle that, design wise, would take a seven-league leap into the future. He sat at his easel and in 10 days, sparsely punctuated with catnaps and snacks, he created the immortal ABC.

On almost any count you can name, this opus started where the competition left off. Its horizontal engine, an in-unit Twin, with a car-type clutch and fourspeed gearbox and with its cylinders set transversely, supplied the Bayerische Motoren Werke with the inspiration that would belatedly yield the BMW. It had overhead valves and single-action carburetor control at a time when flat heads were the norm on street bikes and British riders were forced to twiddle two handlebar levers to blend the gasoline/air charge. Contrasting with the Swannee whistle bore/stroke ratios then in fashion, Bradshaw’s cylinders were way oversquare at 68.6 by 54mm. Spaced no less than 20 in. apart, the cradle tubes of the fully duplex frame not only protected the cylinder heads and overhead rocker gear against crash damage, but served other useful functions that we’ll come to later. Rear suspension, of swinging arm type, anticipated present day practice in everything except the actual springing and damping media, indeed, as far as maintenance of wheel perpendicularity was concerned, it went one better than present designs. Typical of expert reaction to the ABC following its 1919 debut at the first post-WWI London Motor Cycle Show was a comment by Wigram Maxwell, a famous bike journalist of the day: “The technical devotees of the sport gasped in sheer amazement.’’ Twenty-two years later, Arthur Bourne, editor of Motor Cycle magazine, London, recalled this 1919 premiere: “The ABC stand was besieged to an extent without parallel during my whole connection with the game.” As recently as 1967, a published tribute by Phillip Vincent, designer/maker of the late lamented Vincent-HRDs and Vincents, allowed, “Bradshaw’s 1919 ABC was a masterpiece of originality and ingenuity.”

According to the late Mr. Bradshaw himself, who was made an Officer of the British Empire (OBE) for his services to engineering, 45,000 firm orders for ABCs were received within 18 months of the machine’s launching. Nobody contradicted this. In fact, only about 3000 copies, exclusive of a modified version built in France, were ever delivered. Production life of the ABC was an anticlimactic 20 months or thereabouts. For this grand letdown there had to be a reason, as indeed there was. First, however, let’s take a closer look at the design and background of the marque.

The Sopwith ABC, as the transversely engined mode often has been called, wasn’t the first motorcycle of this alphabetical breed. Prior to WWI, ABC had built and successfully raced bikes with their 500-cc horizontal Twin engines set conventionally, i.e., north/ south in the frame. One of their few unusual features, shared with the aircooled engines powering the ABC aircraft and small cars of the period, was very thin steel cylinders, turned from the solid bar, fins, et al. This frighteningly expensive technique, a Granville Bradshaw hallmark, was almost the sole denominator common to the preand post-WWI ABC bikes.

This “masterpiece of originality” had its valves (two per cylinder) interangled at around 50 degrees in cast iron heads and operated by pushrods and rocker arms. Combustion chamber shape was nearer to spherical than merely hemispherical, for the crowns of the aluminum pistons were dished to approximately correspond with the heads’ concavity. This configuration, while doubtlessly fine in theory, set a pretty stringent limit on compression ratio; what the standard ratio was I’ve been unable to discover, but a tuner, writing in a contemporary motorcycle magazine, spoke of raising his ratio to 4.5:1. Incidentally, the use of aluminum for pistons was advanced practice in those days.

The crankcase, split vertically and cast in-unit with the housing for the cone type flywheel clutch and fourspeed gearbox, carried the 180-degree crankshaft on ball bearings. Big end bearings were roller type and circlips retained the wristpins. To the rear of the gearbox, with its 5.48, 7.31, 9.75 and 13.6:1 ratios, bevels drove a cross shaft fitted with a sprocket for the final (chain) stage of the transmission. This was the one department in which BMW, when it finally boarded the cross-engine bandwagon in 1923, outdid ABC in refinement: the Bavarian make, of

course, featured shaft final drive from the start. Bradshaw, in 1920, had been quoted as saying he preferred shafts to chains, but his reasons for preaching one gospel and practicing another weren’t disclosed.

By its own standards or those of any other age, Bradshaw’s engine-gear unit had a uniquely designed-as-a-whole stamp: evidence of forethought was

everywhere, afterthought nowhere (though, as we shall see, it might have been better if he’d allowed himself 10 weeks rather than 10 days for the Creation). Electric lighting systems were a rarity on British bikes in the early Twenties, and most of this minority had their generators hung on extraneously, almost apologetically, and driven by belt. For contrast, the ABC’s generator nested neatly and symmetrically in a tailored housing above the bevel casing and took its drive from the gearbox mainshaft via a spur wheel. Up front, a train of five gears drove the camshaft and the CAV magneto off the nose of the crank.

Engine lubrication was automatic, with the oil carried in a pressed steel sump under the crankcase and circulated by a gear-type pump. A single Claudel Hobson carburetor fed both cylinders through long, snaky induction pipes; to assist quick warmups, these were hot-spotted from the exhaust system, car fashion.

Nearly 20 years before bolt-on crashbars gained so much as a toehold on British bikes (and then only on an exclusive minority of big luxury models), it occurred to the logical Bradshaw to give this function to the constantly-stressed members, i.e., the cradle tubes themselves, and thereby save weight and avoid untidiness. Overall width of the center frame was, as mentioned earlier, an unprecedented 20 inches. And why not? Bradshaw realized, he said, that the distance between the rider’s elbows established the maximum width of the whole man/machine aggregate, so, “Anything within that dimension should be acceptable.”

By splaying his frame out to something not far short of “Bed-stead” gauge, he not only gave his cylinder heads and the rider’s lower limbs ironclad protection but also provided ideal attachments for the most effective weather shielding ever seen. These sheet metal guards filled the spaces between the front and rear pairs of downtubes and tied in along their lower edges with ribbed aluminum footboards. With no pegs to bend or break under impacts, and the footboards mounted inboard and supported on the two main frame cross tubes, buckling of one handlebar control lever probably would be the worst result if you slid ’er to earth. The legshield panels, incidentally, incorporated sliding louvers; these, when manually opened, exposed the cylinder heads to a full air blast; close them and you had a further aid to fast warmups.

Bradshaw, a disarming egocentric to whom his own works were second only in sublimity to the Almighty’s, wouldn’t hear a word against his brainchild and was forever extolling and justifying it. It was, he claimed (the italics are mine), “a self-attending machine that can be taken out at any hour of the day or night, in any weather, without so much as a glance at the mechanism.” Of the ABC’s suspension, which certainly was hard to fault, he said that the springs “worked in unison” and had “a proper periodicity.” They were devoid of shackles and thus needed no lubrication.

Effectively, each rear spring comprised a pair of quarter-elliptics with a common main leaf. At a time when friction shocks were in their infancy and hydraulics had not been invented, interleaf action provided a degree of “natural” damping. Two factors combined to resist torsional whip in the rear frame area: the swinging arms, pivoted on needle rollers, were set no less than 10 inches apart; and the width of the main spring leaves was well in excess of their thickness, making them virtually unbendable laterally. There probably isn’t a bike in production anywhere in the world today whose rear wheel remains so steadfastly and constantly upright in relation to the center frame.

Without specifically relating what the ABC’s whole bone structure weighed, Bradshaw said it was “30 percent lighter than previous designs.” Whose? We’ll never know. It was also “more resilient, yet stronger.” In general, the technical history of the make is poorly documented and hopping with contradictions. The original target weight for the complete machine, dry, was 150 lb., but the lowest figure I’ve seen quoted for production samples was 175 lb. with a full tank and sump—the highest is 300 lb.

Relative to its displacement of 398cc, the ABC in untuned form was a lively performer for its day, responsive to sympathetic throttle fingering and with the short-stroker’s appetite for revs and distaste for slogging. Above all, in the manner of horizontal Twins since time immemorial, it was a standout for sweetness and absence of vibration right through the rpm scale, recalling Wordsworth’s lines . . .

Nor harsh nor grating, though of ample power,

To chasten and subdue.

Within the limitations of an inescapably low compression ratio, various racing celebrities successfully devoted themselves to improving the ABC’s output and reliability. Foremost among these rider/tuners was the late Jack Emerson, who was later to become a mainstay of Jaguar’s racing department during its Le Mans heyday. Emerson, who, pre-WWI, had raced the old longitudinally cylindered ABCs, twice won the Brooklands TT, an annual minor classic, on Bradshaw’s cross-engined babies; in doing so he twice broke the world hour record in the 500and 750-cc classes. Considering that even in the former category he was giving away 100 little cubes, this performance speaks for itself.

Years later, I remember Jack saying that when he accidentally dropped one of those wafer-thin ABC cylinder barrels on the concrete floor of his Brooklands workshop and dented it (the barrel, not the floor), he’d hammer it back into concentricity. I’m still wondering how you wield a hammer, even an itsy-bitsy one, within the confines of a 68.5-mm bore . . .

Other noted ABC whips were Captain G. Maund, who rigged his bike with a dual carburetor system and “solidified” the frame’s back end by junking the springs and running a pair of tubular diagonals between the saddle lug and the rear ends of the swinging arms; Steve Bassett, hillclimb and sprint specialist and a prop of the Cambridge University Auto Club; and Lord Settrington, Bassett’s Oxford University Motor Club vis-a-vis.

Settrington, now the Duke of Richmond and Gordon and owner of Goodwood racing circuit, has some amusing recollections of his youthful love affair with the Sopwith ABC (“D’ you know, I still get a thrill just thinking of it.”). He was interviewed by the dean of Christ Church, Oxford, shortly before examinations for the year.

“Ah, Settrington, yes, let me see,” monologued the Dean; “A little too much motor bicycle racing and not quite enough work, I fancy.”

Comments the Duke in distant retrospect: “I was so shocked that I came home and to my Dad’s (very understandable) fury, sat down and wrote my resignation. Couldn’t face the inevitable failure. With that I presented myself at Bentley Motors Ltd., donned overalls and the rot really set in.”

Alluding to a notorious weakness of the ABC engine, “Freddy” Richmond recalls, “The two holding down studs of the overhead rocker gear often worked loose; then the pushrods were apt to fly out. I lost one when racing a bloke on a Sunbeam from Henley to Oxford—and found the rod over a hedge in an adjoining field.” Assuming that 3000 owners each lost one of the four rods in their time, and that field and hedgerow searches were mostly fruitless (only an heir to a dukedom, surely, could ever be as lucky as Settrington), there still must be a multitude of ABC rods littering rural England.

A researcher’s quest for accurate ABC performance data is constantly frustrated. Bradshaw himself, demonstrably a man with a short memory and a talent for exaggeration, stated publicly that standard engines averaged an output of 16 bhp at the drive sprocket; the maker’s own catalog, on the other hand, put the figure at just half that. Neither authority mentioned the rpm factor in this context, though there is evidence of radically hopped-up ABCs, winding to 6000. If, indeed, stock engines gave as little as eight bhp, tuners of Emerson’s caliber must have stuffed an awful lot of extra buns in the oven, because Jack’s second one-hour record was set at close to 80. (In winning the Victory Handicap during the first interwars Brooklands meet, he had the minor distinction of beating the only girl rider in the lineup, but as Motor Cycle’s report chivalrously suggested, “Perhaps the wind resistance offered by her skirt spoiled her promising performance.”)

In opting (goodness knows why) for 400cc, a displacement incurring a 100-cc disadvantage in the smallest racing class open to it, ABC accepted a penalty that maybe was more apparent than real; comparing the 79 by 100mm measurements of Norton’s contemporary Singles with the two-cylinder ABC’s 68.6 by 54, simple arithmetic shows that these makes’ piston areas were 49.02 and 73.88 square centimeters respectively.

Thus the potential was there, and all it needed, in theory anyway, was the time and the resolve to develop it fully. Time, alas, wasn’t on the Twin’s side. The ABC firm, which derived its initials from a forebear called the All-British (Engine) Company Ltd., farmed out the manufacture of Bradshaw’s creation to a long established English airplane maker, Sopwith Aviation Co. Ltd. The latter, as it soon discovered, had bitten off more than it could chew and went into voluntary liquidation in Sept. 1920, less than a year after the debut that drew “gasps of sheer amazement” from the London Motor Cycle Show audience. The story of the events leading to the project’s collapse can best be told in Bradshaw’s own words:

“The reason the machine went off the market was that we got too many orders—strange but nevertheless true. The firm that had taken on its manufacture was an airplane company, accustomed to building wooden planes and with no facilities capable of coping with 45,000 orders. It was therefore decided to install a million pounds worth of machinery. Thus the firm had to learn how to build a factory, train operatives and manufacture motorcycles all at the same time. When the output stage was finally reached, the 1920-21 slump was upon us ... So the factory and plant were sold, leaving a considerable sum for the stockholders.”

(Continued on page 68)

Continued from page 57

Following the Sopwith debacle, ABC Motors Ltd. (1920) embarked on the manufacture of its own bikes, but this was a dying kick. It’s hard to pinpoint the date when production actually ceased, but late 1921 is as good an approximation as any. Rumors of impending revivals were many in the succeeding months. One published story suggested that Henry Ford’s interest was being wooed. Also, according to Motor Cycle’s Arthur Bourne, “The makers of the BMW were in touch with Bradshaw on the subject of patent rights.” In fact, the first fruits of this BMW/Bradshaw dalliance was an east/west side-valve engine, as distinct from a complete machine, that BMW made available to the German bike industry at large, in or around 1922.

Meanwhile, backtracking a bit, a French ABC, made under license by another aircraft company, Gnome et Rhone, was meeting a happier fate. The Gallic version was made in two capacities, 400 and 500cc, and stayed the course until 1923 or ’24. Only one Gnome et Rhone ABC is known to survive-in Australia-where it rubs elbows with two British ones in the collection of a local connoisseur.

The French rendering was superior in several respects: better kickstart, lighter gearshift, modified engine lubrication system, ribbed light alloy sump, valve clearance adjusters transposed from the rockers to the pushrods, Zenith rather than Claudel carburetor, extra instrumentation, etc. The half-liter editions, with their bores unchanged but the strokes lengthened to 67.5mm, stayed just oversquare.

In a multiplicity of details, as well as fundamentals, the Sopwith ABC was a monument to Bradshaw’s “originality and ingenuity.” For instance, parking was facilitated by a stand with counterpoise action that enabled the bike to be hoisted with one hand. Nut and bolt head sizes were rigorously minimized; just two spanners were supplied with the machine and these were claimed to cover all conceivable owner requirements. The metal box that housed them occupied a neat and invulnerable position directly beneath the gearbox. Immediately behind the carburetor and designed into its surroundings was a pressed steel container for spare lamp bulbs and other electrical items. The handlebars, being fully adjustable, were years ahead of the competition in general, and following the American (not English) example, all control wires passed through the bars instead of being draped nakedly and untidily along the outside.

Almost everything that needed periodic attention on the allegedly selfattending ABC was easy to get at, and by undoing four bolts the complete engine-gear unit could be lifted out bodily. By dislodging the knock-out spindles, the wheels could be removed in moments, leaving the driveline in situ in the event of a back tire blowout or similar trouble. Several years before internal expanding brakes came into common use, and indeed before most British makes had front brakes that were any damn use at all, Bradshaw endowed his ABC with drum type binders that were fully abreast of the best car practice. Incidentally, he described them as self adjusting, but I never heard or read elsewhere of this labor saving attribute.

Although the handling, road-holding and overall deportment of Sopwith ABCs are naturally rated highly by the handful of vintage-bike connoisseurs and collectors who own and treasure these machines today, the realistic judgement is, more simply, that they were ahead of their time. At a date when only a small minority of the world’s motorcycles had rear springing, and few of the available systems worked, Bradshaw’s swinging arm suspension gave a really comfortable ride and contributed valuably to roadability. Stability was surely helped, too, by the bike’s low center of gravity—15 in. above ground level. On wet or slimy surfaces the front wheel tended to skid, but a ribbed tire took care of that, at least partially.

With characteristic modesty, at a pre-launch gathering of press people and other interested parties in 1919, Bradshaw claimed, “Every single worry that motorcyclists have come to accept has been removed at a single cut.” Seldom has so much optimism and wishful thinking been packed into a single sentence, as can be gathered from the subsequent writings of that weighty authority, Arthur Bourne.

Bourne, who’d been the ACU’s engineer before switching to the editorship of the world’s largest-selling motorcycle magazine, had a love-hate relationship with ABCs: loved them for their incomparably scientific, ingenious and forward-looking basic design, hated them for their undependability and many detail faults.

Among other criticisms, Arthur asserted, “Burst engines were not infrequent,” also that the ball bearings carrying the crank were of a “light fan type” prone to failure, that neither the engine lubrication system nor the circlips used for wristpin retention were up to their job, that the top gear dogs “became nosed off,” that the cams were too narrow and wore fast, that the transversely operated kick-start was “not a great success,” that the standard valves were weak (there was a proprietary valve called the celerity with which most enthusiast owners, following the customary pulverizations, replaced the original article).

These criticisms were published while Bradshaw was still alive and verbally kicking, and how he verbally kicked. If his engine “burst not infrequently,” why did it twice break the 500and 750-class world records? And how is it that the standard power unit didn’t fail at the bench test to which it was invariably subjected, viz, two days and nights on full load?

Before ABC production started, Bradshaw had claimed, “Owing to the design of the ports, there is no fear of a broken valve smashing a piston.” (What! Broken valves on a self-attending motorcycle?) Arthur Bourne, as it developed, was later able to put this boast to the test. He, like every other ABC owner, broke a valve far from home, but in 45 minutes he was back in business, having removed the cylinder head, extracted the decapitated valve, and stuck the head back on again.

Experiences like Lord Settrington’s with hedge-hopping pushrods were the common lot of the ABC fraternity, the result being that the making and marketing of nonstandard rocker gear gradually assumed the proportions of a folk industry. Features shared by most of these bolt-on kits were oil reservoirs (Bradshaw’s design surprisingly made no provision for top end lubrication) and lengthened rocker bearings. For once Bradshaw abandoned his familiar anythin g-y ou-can-do-I-can-do-better position on the subject of the rocker gear’s shortcomings and admitted—with qualifications—that he’d boobed a bit. He ought, he allowed, to have given himself a mite more east/west latitude in dimensioning his engines; it still wouldn’t have projected beyond the frame tubes on either side. As it was, though, “I cramped the overhead rocker gear a little too much.” It nevertheless was “scientific in every action,” and he attributed the trouble with fugitive pushrods to “enthusiasts who sit and race up their engines with the machine stationary.” Because the vaive springs were on the short side, these conditions resulted in loss of their designed tension, due to overheating.

Unable to resist a parting sideswipe at the vendors of replacement rockers and attendant bits, Bradshaw closed his dissertation by saying, “We got over this trouble in the end by using heat insulators, more coils and twin springs—not by altering the pushrods or rockers.”

(Continued on page 70)

Continued from page 69

Although gearshifts on ABCs, unlike conventional machines, involved meshing teeth rather than dogs on the three indirect ratios, changes were sweet and easy. Going up through the gate, though, it was necessary to choose to do either an Emerson, i.e., slamming the lever through with the throttle wide, or changing so measuredly that it would be possible to take a coffee break while shifting between gears. When Bourne got off a mild beef in this sense, Bradshaw’s reaction was, well, why not do an Emerson? Jack’s gearbox and clutch were dead standard and had never yet shown resentment of treatment that habitually gained him a half mile lead on his nearest pursuer on a standing start lap of the 2 3/4 mile Brooklands track . . .

Considering he’d apparently convinced himself that the motorcycling millennium had dawned during the 10 days it took him to create the Sopwith ABC, it’s curious that Granville Bradshaw felt it unnecessary to change the crosswise horizontal Twin concept when designing subsequent bike powerplants. These included vertical 350-cc Singles with oil cooling and a 250-cc Twin—the Panthette, or Little Panther—with east/ west cylinders, but in V formation.

Returning to the question of the overall reliability of the Sopwith ABC engine, it’s worth mentioning that one of these controversial Four-Hundreds was once used to power a light airplane . . .and “flew it satisfactorily,” according to Bradshaw. Two other earlier and even more improbable applications of ABC engines are on record. The first and wackiest of these projects, dated 1908, was a flying machine “with wings that flapped like a bird’s,” and which in theory had a vertical takeoff capability (in practice its takeoffs were oblique, of about a second’s duration and instantly followed by nosedives to terra firma). Project two was a windwagon, a cyclecar propelled by an airscrew, of which a Light Car road tester reported in 1921, “It refused to climb a gradient of 1 in 60 in. but, running with the wind, developed a breakneck speed and an uncontrollable desire to capsize.”

Boffinissimo Bradshaw, it’s only fair to add, was not involved with either of these heathenish devices, or at most, only insofar as he may have designed their engines.

One more thing he didn’t do. He didn’t originate crosswise mounting for horizontal Twin engines in motorcycles. The unsung designer of a British twostroke called the Economic did, beating ABC to this world first by a short head. But that is another story.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

August 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Departments

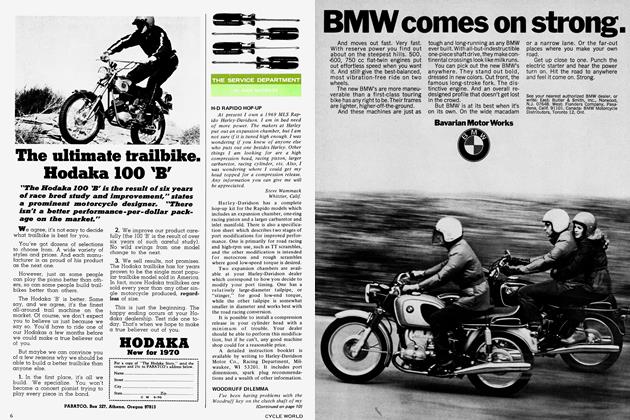

DepartmentsThe Service Department

August 1970 By Jody Nicholas -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1970 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

August 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

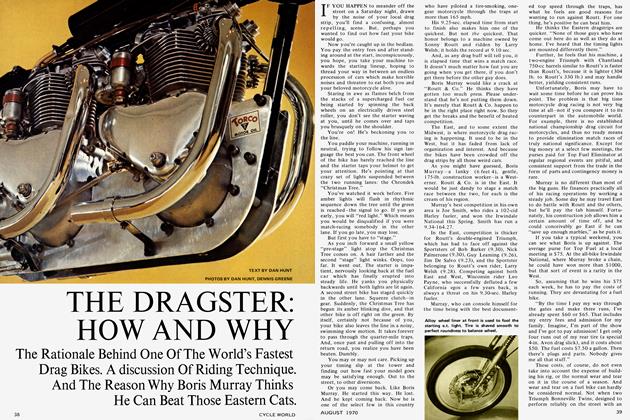

Special Features

Special FeaturesThe Dragster: How And Why

August 1970 By Dan Hunt -

Features

FeaturesThe Princess & the Peasant

August 1970 By Cecil P. Mack