CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

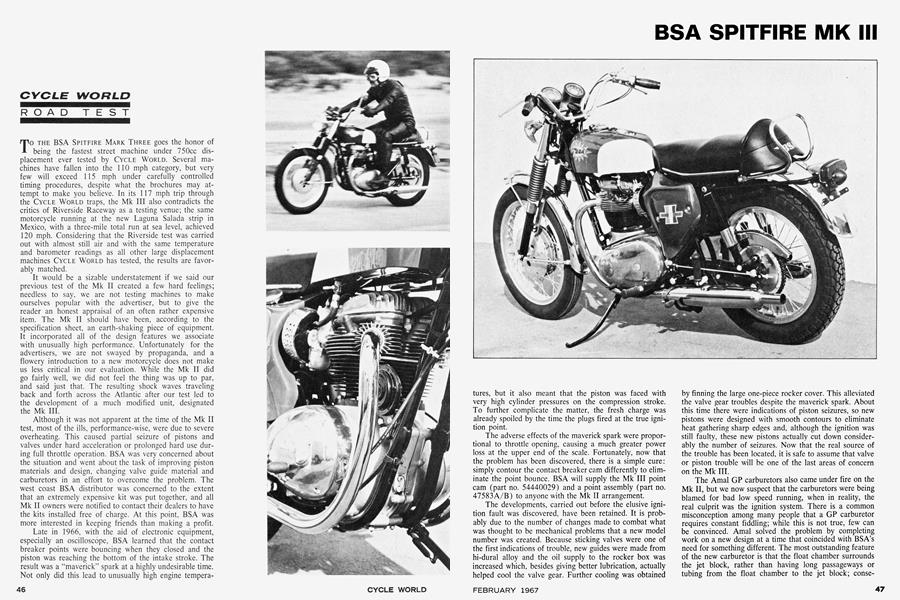

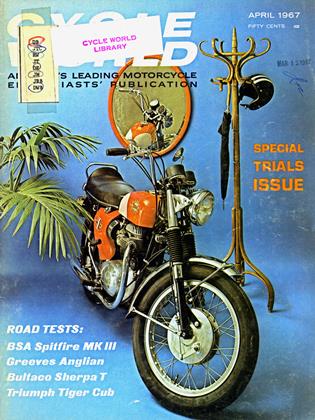

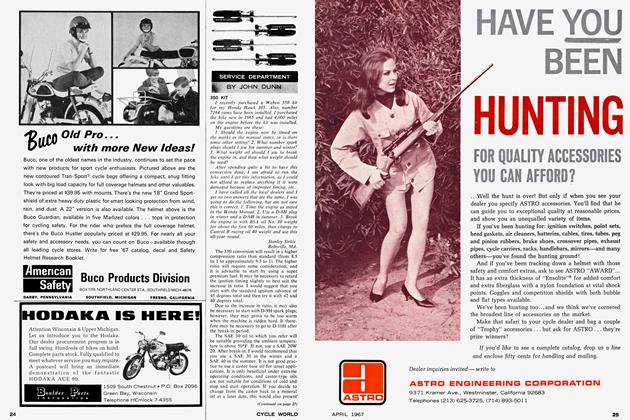

TO THE BSA SPITFIRE MARK THREE goes the honor of being the fastest street machine under 750cc displacement ever tested by CYCLE WORLD. Several machines have fallen into the 110 mph category, but very few will exceed 115 mph under carefully controlled timing procedures, despite what the brochures may attempt to make you believe. In its 117 mph trip through the CYCLE WORLD traps, the Mk III also contradicts the critics of Riverside Raceway as a testing venue; the same motorcycle running at the new Laguna Salada strip in Mexico, with a three-mile total run at sea level, achieved 120 mph. Considering that the Riverside test was carried out with almost still air and with the same temperature and barometer readings as all other large displacement machines CYCLE WORLD has tested, the results are favorably matched.

It would be a sizable understatement if we said our previous test of the Mk II created a few hard feelings; needless to say, we are not testing machines to make ourselves popular with the advertiser, but to give the reader an honest appraisal of an often rather expensive item. The Mk II should have been, according to the specification sheet, an earth-shaking piece of equipment. It incorporated all of the design features we associate with unusually high performance. Unfortunately for the advertisers, we are not swayed by propaganda, and a flowery introduction to a new motorcycle does not make us less critical in our evaluation. While the Mk II did go fairly well, we did not feel the thing was up to par, and said just that. The resulting shock waves traveling back and forth across the Atlantic after our test led to the development of a much modified unit, designated the Mk III.

Although it was not apparent at the time of the Mk II test, most of the ills, performance-wise, were due to severe overheating. This caused partial seizure of pistons and valves under hard acceleration or prolonged hard use during full throttle operation. BSA was very concerned about the situation and went about the task of improving piston materials and design, changing valve guide material and carburetors in an effort to overcome the problem. The west coast BSA distributor was concerned to the extent that an extremely expensive kit was put together, and all Mk II owners were notified to contact their dealers to have the kits installed free of charge. At this point, BSA was more interested in keeping friends than making a profit.

Late in 1966, with the aid of electronic equipment, especially an oscilloscope, BSA learned that the contact breaker points were bouncing when they closed and the piston was reaching the bottom of the intake stroke. The result was a “maverick” spark at a highly undesirable time. Not only did this lead to unusually high engine temperatures, but it also meant that the piston was faced with very high cylinder pressures on the compression stroke. To further complicate the matter, the fresh charge was already spoiled by the time the plugs fired at the true ignition point.

BSA SPITFIRE MK III

The adverse effects of the maverick spark were proportional to throttle opening, causing a much greater power loss at the upper end of the scale. Fortunately, now that the problem has been discovered, there is a simple cure: simply contour the contact breaker cam differently to eliminate the point bounce. BSA will supply the Mk III point cam (part no. 54440029) and a point assembly (part no. 47583A/B) to anyone with the Mk II arrangement.

The developments, carried out before the elusive ignition fault was discovered, have been retained. It is probably due to the number of changes made to combat what was thought to be mechanical problems that a new model number was created. Because sticking valves were one of the first indications of trouble, new guides were made from hi-dural alloy and the oil supply to the rocker box was increased which, besides giving better lubrication, actually helped cool the valve gear. Further cooling was obtained by finning the large one-piece rocker cover. This alleviated the valve gear troubles despite the maverick spark. About this time there were indications of piston seizures, so new pistons were designed with smooth contours to eliminate heat gathering sharp edges and, although the ignition was still faulty, these new pistons actually cut down considerably the number of seizures. Now that the real source of the trouble has been located, it is safe to assume that valve or piston trouble will be one of the last areas of concern on the Mk III.

The Amal GP carburetors also came under fire on the Mk II, but we now suspect that the carburetors were being blamed for bad low speed running, when in reality, the real culprit was the ignition system. There is a common misconception among many people that a GP carburetor requires constant fiddling; while this is not true, few can be convinced. Amal solved the problem by completing work on a new design at a time that coincided with BSA’s need for something different. The most outstanding feature of the new carburetor is that the float chamber surrounds the jet block, rather than having long passageways or tubing from the float chamber to the jet block; consequently, its name — “concentric.” This “in-unit” arrangement ensures a more constant float-to-jet relationship, regardless of the machine’s angle of lean.

A pair of 32mm concentrics with separate air cleaners are fitted. A rubber O ring is used in place of gaskets at the cylinder-head to carburetor flange. If the carburetors are removed from the engine, care should be exercised during reassembly to ensure even mounting bolt pressure; otherwise, the carburetor bodies will distort, causing the slides to bind. The intake ports are clean and well formed in standard trim, and blend nicely into the large 1-19/32 intake valves.

A somewhat unusual practice is the use of forged aluminum connecting rods, although the BSA group has been doing it for several years. Connecting rods are in the same category as pistons regarding strength; the heavier they are, the stronger they must be. Not only is the rod faced with forces from both ends, but its own weight is an increasing handicap as the rpm go up.

We strongly criticized the front brake on our previous test. Braking at high speeds produced a vicious chatter. On our Mk III test, however, the brakes were among the best of any touring machine we have ever ridden. The front unit, especiallv, is silky smooth and a marvel of efficiency. At Riverside, where braking was being done in racing fashion, well into the turns and banked over, the brakes imparted a comfortable feeling of safety and confidence.

General handling falls into the English big bike category; at rest, it is somewhat akin to a truck, but once underway, even at low speeds, things fall into place and it becomes very navigable. Although it is not necessarily a fault, the machine never lets the rider completely forget that he is on a large motorcycle.

The fact that the Mk III does not feel cumbersome, usually caused by excessive weight high on the machine, can be accounted for, in part, by the small lightweight gas tank. While the tank contributes a good deal towards handling, it does not do much in the way of long distance touring. Under the normal high speed cruising to which the Mk III is apt to be subjected, the fuel range is considerably less than one hundred miles. The tank has a single point hold down through the top and is easily removed to carry out work on the top of the engine. With the gas tank off, it is a simple matter to remove the large single rocker cover and completely expose the valve gear for servicing.

Because the Mk III is pulling a relatively high gear ratio, the engine is turning a leisurely 3,500 rpm in top, at most legal highway speeds. Up to this point, there is no trace of vibration, and the engine is virtually turbine smooth. After 4,000 rpm, however, there is vibration similar to, but not worse than, other machines in this displacement category. The vibration is probably more noticeable at the higher speeds due to the almost complete lack of it below 3,500 rpm. Considering the Mk III is a high performance machine, the engine is surprisingly tractable throughout the rpm range. There is not a point where things suddenly burst into life; the power simply increases with rpm. From engine speeds as low as 2,000 rpm, torque is sufficient to accelerate smoothly with plenty' of urge.

Even when the engine is warm, it is necessary to use the choke to bring it to life. Some of the reluctance to fire on the first kick can be attributed to the kick starter ratio which, because of the high compression engine, is designed to favor someone with less brawn than Hercules. Unfortunately, gaining mechanical advantage for the rider results in a slow engine cranking speed.

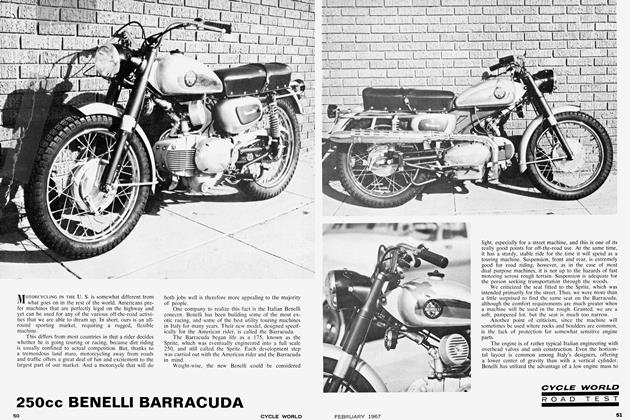

In external appearance there is little doubt that the Spitfire has been custom made for the American rider. Out of the box it incorporates most of the changes we have been making to English motorcycles for years. The small gas tank is a particularly American trend. An unfaired headlight, rubber fork covers and separate speedometer and tachometer have been fitted. Both tach and speedo are on a plate from the top fork crown, but are isolated from vibration by mounting them in rubber cups. The fenders offer adequate protection from the elements and they are small, chromed and in good taste. Alloy rims give a little extra sporting flavor to the Mk III.

The riding position is very comfortable. Handlebars are slightly raised, but offer good control at all speeds. Particular attention has gone into passenger comfort and safety by incorporating a small back on the dual seat and a rear handhold.

BSA is to be commended mostly on the muffler design. Obviously, from the performance figures, the mufflers are very efficient in terms of gas flow. What is more important is that the exhaust noise level is unusually low for a machine of this size.

Regardless of what form anti-motorcycle legislation takes, or what excuse is given for it, the very basic reason it gets support from the general public is because of noise. We take off our hats to manufacturers who realize the situation and do something about it.

BSA

SPITFIRE MK III

$1466