HOT MOTORS ON THE HORSE TRACKS

J. L. BEARDSLEY

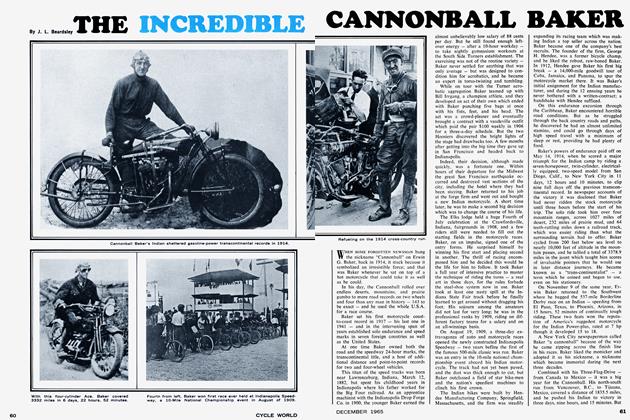

AT THE END OF THE FIRST World War, motorcycle manufacturers hurried to reassemble their professional racing teams in order to rekindle the public’s pent-up enthusiasm for the sport, which the intervening war years had interrupted.

For years, the keen competition and close finishes seen on the flat tracks in sprint and medium-length championship programs had been building motorcycle racing into a popular spectator sport.

Again in 1919, a thrill-starved public — most of whom had never ridden a motorcycle — flocked to the mile and half-mile dirt ovals to revel in the thundering duels of Class A professionals on the hottest race jobs the big factories could produce. What they saw was big-time motorcycle speed at its spine-tingling best.

The old-time factory pros, riding on a salary-plus-purse basis, had the flat track technique developed to a science. Purses were never big, but prestige was involved, and competitors rode the curves with what looked like sheer madness, but was actually perfect coordination of man and machine.

The old pro daredevils always put on a better show on the dirt circuit than the autos did, boasting better time and close finishes that were Classics in Speed.

As early as 1913, Carl Goudy, the great Excelsior star, rode to fame on the Columbus, Ohio, Driving Park mile oval, setting a 100 mile World Record of 92 minutes, which was eight minutes better than Ralph De Palma’s auto mark, made a week later at Brighton Beach, New York.

And the bike jockeys went right on building a big-time sport on the horse tracks across the country, when horsepower displaced the hayburners.

Motorcycles were a spectacular feature of the post-war Golden Age of Sport, and the two-wheelers got off to a roaring start in the 200 mile track championship at Ascot Speedway, Los Angeles. Some 10,000 fans thrilled to a great exhibition of skill and daring when the big-time pros put their reputations on the line, June 22, 1919.

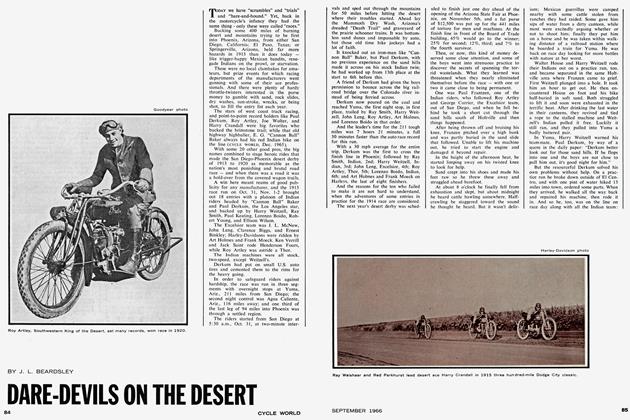

Harley’s “Wrecking Crew,” Ralph Hepburn. Red Parkhurst, AÍ “Shrimp” Burns and Ray Weishaar were there; while their bitter rivals on Indians were Bill Church, Dave Kinney, Bob Newman and Ralph Sullivan.

Others included Roy Artley, west coast road record champ; Wells Bennett, endurance expert; with M. Tice carrying the Chicago-built Excelsior colors.

Ray Weishaar roared into the lead with Hepburn pushing him hard until the 20th lap, when he passed the Wichita Wildman. The battle went on for 60 more hectic rounds until Weishaar took over again.

Red Parkhurst now took a slice of the action at a furious pace; and Roy Artley, Bill Church, and Wells Bennett were moving up, with Bennett dishing out some extra thrills in terrific bursts of speed.

Tires and mechanical troubles started after 70 miles, but the amazing pit work of the Harley-Davidson crew kept their riders well ahead. This well trained outfit changed a rear wheel and filled oil and gasoline tanks in a record 38 seconds. Guns holding 2 to 3 gallons were used in refueling.

Weishaar still led at 100 miles, followed by Hepburn, AÍ Burns and Earl Roylance, H-D, so the “Wrecking Crew” was still in command.

At 150 miles, Hepburn was out front with an average of 72.32 mph, which was a full two miles an hour faster than Roscoe Sarles’ winning average in an auto race on this track two weeks before.

Hepburn could not be headed and led the field home in 2:45.54.6 to win the 3 feet-tall silver Firestone Trophy, the Harley-Davidson Cup, and $650 in cash. Bill Ottaway, Harley’s expert speed tuner and team manager, shared in this victory when his boys captured the first five positions, and ran the entire race without a mechanical failure.

It was a big Fourth of July in Baltimore, Maryland, that year, too, when the Harleys had a field day on the half-mile oval. AÍ “Shrimp” Burns starred by winning three out of six events, handing the eastern pros their first defeat since 1915. This track was practically owned by the sensational K. H. “Krazy Hoss” Verrill, Gary Mears and “Sliding Ed” Hill, until Burns made them look like amateurs with one trade paper labeling him “The Oakland, California, Boy Wonder.”

“This boy Burns, of only 19 summers, sure can ride the turns,” they wrote, adding, “A more wonderful exhibition on these sharp curves has never been seen before. He held a scant 18 inches off the inside rail ... It was never a question of winning, but could he stay on his wheels at this suicidal pace?”

Columbus, Ohio, is still the competition capital, and the old Driving Park mile was the scene of much thunder-bike history in the old days.

The 50 mile Free-For-All, for instance, on July 14, 1919, loomed as a clash between Harley aces, AÍ Burns and Red Parkhurst and the great Indian team of Jim Davis and Gene Walker. The intense rivalry got a little out of hand when Burns and Walker, racing wheel-to-wheel in a 5 mile heat, began swinging punches at each other down the stretch. This had to be called “No Contest,” but what happened afterwards under the grandstand, was not reported.

AÍ Burns was back to take a 10 mile event; but Jim Davis, had his Indian warpaint on in the 50 mile feature and led most of the way, until his motor fouled and Hepburn and Parkhurst ran one-two for another Harley victory.

The iron-horsemen invaded Detroit, and crowds at the closing-day speed program of the Michigan State fair on September 7, 1919, saw some hot motorcycle contests by the Class A pros.

The feature was the 25 mile National Sidecar Championship on this Motor City mile circuit, which brought out the best men in the business. Floyd Dreyer rode an Indian Flexi; Al Burns, Harvey Garn, Crowell & Kaiser of Detroit were on Harley Flexis; W. P. Governor rode a Harley rigid frame job; and L. P. Stone carried the Excelsior colors.

At the “go” flag, the line thundered away in a beautiful start, but Governor built up a 50 yard lead on the first lap. This wasn’t enough to hold off Floyd

Dreyer, who surged past in the 3rd round like he was riding solo. With his pas-

senger pulled far inside the shell, Dreyer laid into the turns wide open and showed the advantage of the flexible design over the rigid for real speed. To offset this, Governor’s passenger crawled far out and lay over the outside wheel on the curves, in violation of the M. & A. T. A. racing regulations. When warning flags were ignored, they were disqualified. It was

Dreyer’s race in 28:14.8, with “Shrimp” Burns, H-D, 2nd; Leo Crowell, H-D, 3rd.

Don Marks, Indian, and AÍ Burns, H-D, were featured in a two-mile match event, and Burns had to set a new track one-lap record of 48 4/5 to win.

Colorado was always prime territory for bikes and racing, so Denver’s big meet, which followed Detroit on September 27, packed 30,000 fans into the Overland Park mile track stands.

It was a triumphant home-town appearance for Leslie “Red” Parkhurst, famed Harley-Davidson rider, who rode his 8 valve in a clean sweep of all solo events.

In a 5 miler Bob Perry, Excelsior, and Gene Walker, Indian, pushed Parkhurst to the limit. But he edged out a win, outlasting Gene Walker to win the 10 mile open class when Perry, Creviston, and Hugh Murray all went out with mechanical troubles.

The 25 Mile Rocky Mountain Championship went to Parkhurst over Bob Perry, Excelsior; Gene Walker, Indian; Fred Nixon, Indian; “Shrimp” Bums, H-D; and Roy Creviston, Indian.

Stars of highest rank were also seen in the sidecar events, when Frank Kunce took two events over Floyd Clymer and “Speck” Warner. All were regional champs with a national following. Another big meet was held here the following year.

In Los Angeles, the famed Ascot Park temple of speed saw the first championship action of 1920 on January 11, drawing a record west coast closed-track crowd of 25,000.

In the 25 mile National, AÍ Burns, now riding an Indian, tore out in front at a suicidal pace. He was chased by Otto Walker, H-D, and Bob Newman, Indian, who took turns leading, depending on who held the groove best. Burns, who managed to be on top at 5, 10, 15 and 20 miles, set new track marks for all distances, ending with a smashing win at 80.89 mph.

The 50 mile Ascot Championship was another thriller, and a bruising free-for-all that shook up the crowd with its desperate riding and spills.

First Ray Weishaar, H-D, blew a tire on the back stretch, went down, but was not hurt (though it looked bad from the stands).

Later, Bill Church, Indian, led Joe Wolters, Ex., into a too-fast turn, and another tire let go, skidding Church and his bike across the track in a trail of flaming gasoline.

Wolters proved his great courage by throwing his own machine down to avoid hitting the prostate Church. Spectators leaped to their feet, but, fortunately, neither rider was seriously hurt in this melee.

Harley’s ace distance rider Otto Walker, provided the final thrill of the day, when he went into a fast turn trying for second place in the last mile. To avoid hitting the fence, he was forced to throw his machine down, missing the fence by inches. But he jumped back on — much to the relief of the spectators — and came in third. AÍ Burns and Bob Newman on Indians, were one and two in this clambake, which was pretty wild even for old Ascot.

The hay-burners still run on the famous old North Randall mile track south of Cleveland, Ohio, but back in 1920 the bikes and autos performed there.

No fan could have dreamed up a more perfect speed fest than the motorcycle meet at Randall on September 19, 1920, when all the stars of professional racing clashed at this beautiful oval.

First came the dash for the National One-Mile Championship between Gene Walker, “Shrimp” Burns, and Don Marks on Indians; Jim Davis, Ralph Hepburn, and Freddy Ludlow on Harleys.

“They volleyed into the turn like pellets from a choke-bored shotgun,” one sports writer put it. It looked like they took the back stretch in one long jump, roaring toward the finish line, with Gene Walker streaking across first, breaking his own one-mile record in 45 2/5 seconds.

The 5 mile sidecar event was a sizzling duel between Floyd Dreyer and Sam Riddle, Indian Flexis; Jiggs Price and W. P. Governor oh H-D Flexis. Price rode all-out to pass both Riddle and Dreyer, winding up with the fastest 5 miles ever made by a sidecar up to then, a 4:33 3/5 record.

Gene Walker next blazed through to a new 5 mile solo mark of 3:51.

Dreyer and Price staged a relentless battle in a 10 mile sidecar sprint, but Dreyer’s desperate burst of speed at the finish fell a few feet short. It was another national record of 9 minutes 10 seconds.

The 10 mile solo was still another new mark, when AÍ Burns, on his pocket-valve Indian, topped Harley great Jim Davis in a snappy 7:53.

In the 25 mile feature, Indian’s star Gene Walker tangled with Fred Ludlow, a formidable Harley opponent. Walker maintained an edge until he spilled in the late stages. Then it was Ludlow all the way. Jim Davis was a close second, and Don Marks, 3rd, after Hepburn locked a wheel in the final lap and went out.

The final 1920 National Championship meet was held at Readville, Massachusetts on October 23. There, Indian team ace Gene Walker clipped a fraction from his 5 mile record by a win in 3:50 4/5 and Jiggs Price hung up a new national sidecar 2 mile mark of 1:49 1/5.

The 10 mile National was mishandled by officials. Seven riders were allowed to start instead of six as specified by the rules. The Indian team protested. An elimination heat was ordered, with the seventh man to finish eliminated; but this happened to be Gene Walker, who had plug trouble. He held the 10 mile record, and it was argued he should have another chance with his engine in running condition. However, this was not allowed, so the entire Indian team walked out on the event.

(Continued on page 92)

Ralph Hepburn then proceeded to win the “championship” over his Harley teammates; but despite this hassle, the crowd of 10,000 soon forgot it in the hot duel between Jiggs Price and Floyd Dreyer in the two mile sidecar event, and later the exciting 25 mile Massachusetts Motorcycle Association Championship, won by Hepburn, H-D.

It was the first big-time meet in New England in five years, and with local favorites showing well, it was a great comeback for the bike sport in the Bay State.

Toledo, Ohio, was another top-speed arena in the bike racing boom of the 1920s, and the Ft. Miami mile was wide, almost dustless and very fast. It was a temptation for the swiftest action, and many records fell in the hot competition, rivaling Syracuse in record production.

The Toledo arena had a grim price for all its speed, however. In 1922 the great AÍ “Shrimp” Burns took his last ride there, August 13th. He was riding the same #50 Indian that, shortly before, carried old-time star Charley “Fearless” Balke to his death at Hawthorne in Chicago.

The big three-day rally planned for July 24-25-26, 1924, at Toledo, again

brought tragedy, when Paul Bower hit the fence in practice on opening day, sustaining fatal injuries.

Otherwise, this was a typical classic contest of the old champions, especially on the closing day, when Jim Davis and Ralph Hepburn on Harleys, met Johnny Seymour and Paul Anderson on Indians, in a thriller for the 10 mile 30.50 class National crown. Davis hung up a new record to win it.

“Dynamite” Scott needed another record to win the 61 inch sidecar 10-mile title; and Davis reeled off the fastest 25 miles ever done on a 30.50 motor, to take the National Title in this event, timed at 20:10 1/5.

Harley’s hometown, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, had a fine mile dirt track where all the old motorcycle champs appeared up until the course was paved in 1954.

Some notable history was made there on August 9, 1925, when Eddie Brinck won the 10 mile 30.50 National over Jim Davis and Joe Petrali (all on Harleys) before a crowd of 30,000 fans. The 5 mile Open went to Davis over Johnny Seymour, Indian, and Petrali.

Then, for the first time on any track, Harley-Davidson introduced their new 21.35 inch race jobs and Eddie Brinck, Dayton, Ohio speedster, proceeded to win the 5 mile heat on these small engines in 4.20; and a 10 mile event over Jim Davis and Johnny Vance, in 8:45 1/5.

Bill Minnick scored in the 10 mile sidecar Open and again in the 25 mile National for 21.35 inch class.

The little jobs caught on, and were popular for years on all kinds of tracks.

But championship racing never flourished better than on the Syracuse, N.Y. fairgrounds mile oval. Probably more champions were crowned and more records set during the New York State Fair, than any other place over the years.

One memorable date was September 19, 1925, or “Johnny Seymour Day,” as the papers afterwards called it. For Johnny, on his 30.50 Indian, set four world records and won three National Championships in a splurge of sensational riding.

A crowd estimated at 65,000 had watched a 100 mile auto race, before the iron horsemen fired up their mounts. Then things happened fast.

First, Seymour set a new track record of 44.30 seconds in qualifying, then defeated Harley aces Joe Petrali, Jim Davis and Curley Fredericks, in the 5 mile National, setting a new record time of 3:43.78.

Seymour then demolished three more records in succession: the 10 mile National in 7:30.40; the 15 mile Michigan State Championship in 11:19.60; and the 25 mile National in 19:15.65.

“Seymour made brilliant history,” the Syracuse American said. The Syracuse Herald went further with, “Seymour’s achievements for the day are without a parallel.”

In 1928, the year that The American Motorcycle Association took control of racing, the Syracuse Fair meet, September 1, was another carnival of tremendous speed that might have been called “Jim Davis Day.”

This time 76,000 spectators were on hand to see Davis at his brilliant best, when he added four Class A records to the long list of Indian laurels.

The 5 mile National 45 inch title went to Davis in 3:55.75; Art Pechar — direct from a successful British tour — was 2nd; and Curley Fredericks, 3rd, both on Indians.

The 15 mile National for 21.35 inch engines was a super-human effort by Davis, when he gunned the little machines to break all existing records up to 45 cu. in. with a terrific 11:51.35 time.

Syracuse, the top eastern dirt track, began to crown champions in 1921, when Freddy Ludlow streaked to five National titles there in a single explosive afternoon at 1, 5, 10, 25 and 50 miles — the last a National record.

In 1931, a decade later, Joe Petrali, then mopping up everything for HarleyDavidson, paid it a visit. Fresh from 5 and 10 mile Class A wins at Milwaukee, the amazing Petrali took the 21.35 class titles at Syracuse, on September 12, at the same distances.

He was National 45 inch Champ in 1932; and the next year in two appearances at the Reading, Pa., 1/2 mile track, Petrali won the 3, 5, and 8 mile Nationals. He added the mile-track 10, 15 and 25 mile Nationals for a smashing 1933 season.

That was the way the old Pros did it, and the great Petrali was the last of his rugged breed. Being Harley’s last salaried rider in 1934, an era ended with Joe, and in the 61 inch racing specials, loaded with 110 pounds of air in their thin tires, no longer went power-sliding the old “dusters.”