THE INCREDIBLE CANNONBALL BAKER

J. L. Beardsley

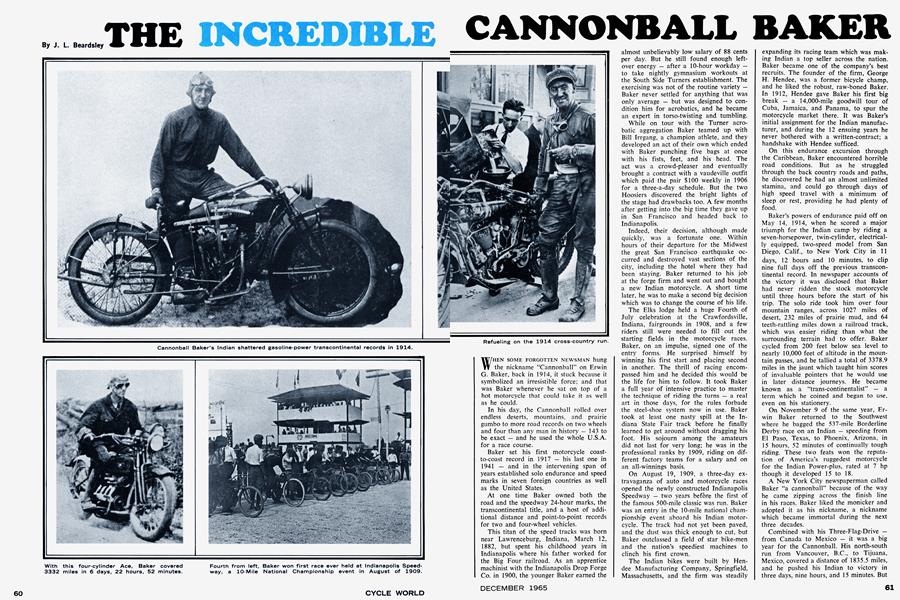

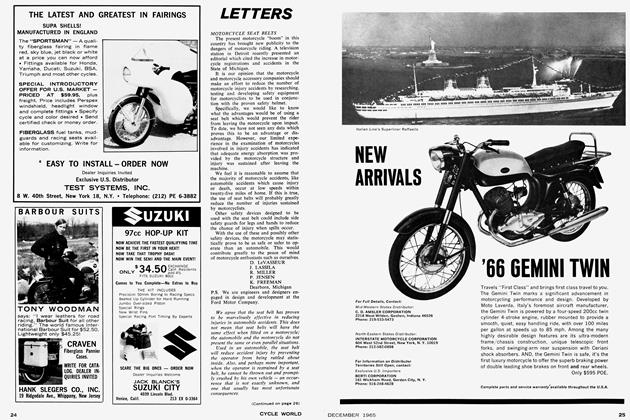

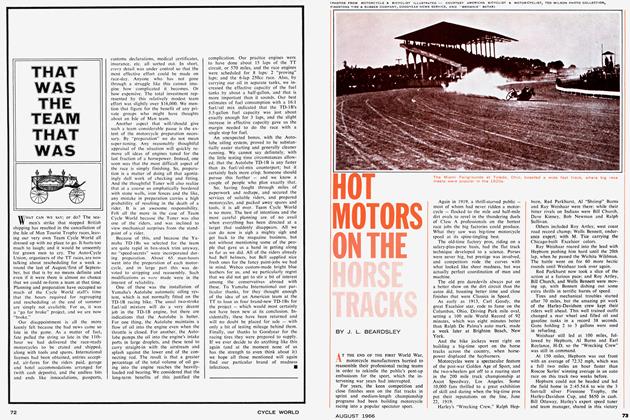

With this four-cylinder Ace, Baker covered 3332 miles in 6 days, 22 hours, 52 minutes.

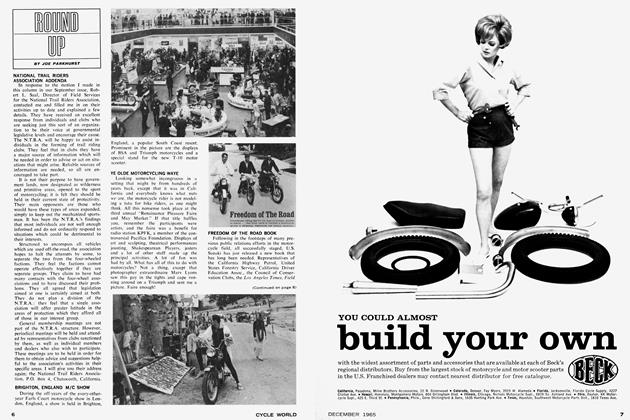

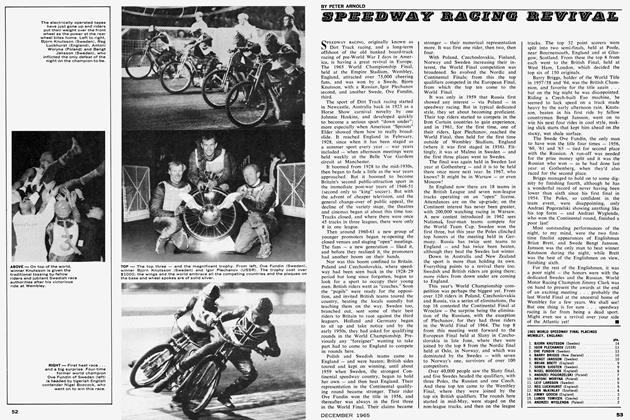

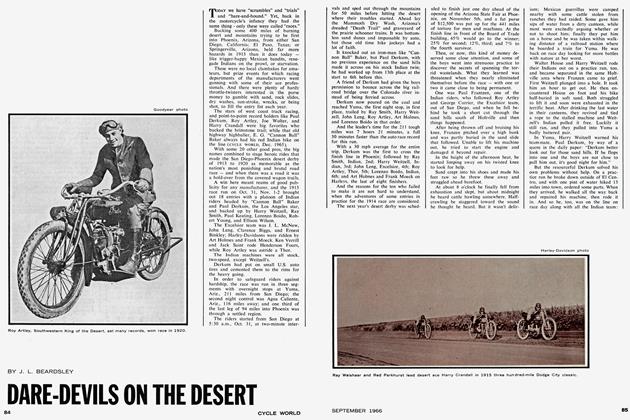

Fourth from left, Baker won first race ever held at Indianapolis Speedway, a 10-Mile National Championship event in August of 1909.

WHEN SOME FORGOTTEN NEWSMAN hung the nickname "Cannonball" on Erwin G. Baker, back in 1914, it stuck because it symbolized an irresistible force; and that was Baker whenever he sat on top of a hot motorcycle that could take it as well as he could.

In his day, the Cannonball rolled over endless deserts, mountains, and prairie gumbo to more road records on two wheels and four than any man in history — 143 to be exact and he used the whole U.S.A. for a race course.

Baker set his first motorcycle coastto-coast record in 1917 his last one in 1941 and in the intervening span of years established solo endurance and speed marks in seven foreign countries as well as the United States.

At one time Baker owned both the road and the speedway 24-hour marks, the transcontinental title, and a host of additional distance and point-to-point records for two and four-wheel vehicles.

This titan of the speed tracks was born near Lawrenceburg, Indiana, March 12, 1882, but spent his childhood years in Indianapolis where his father worked for the Big Four railroad. As an apprentice machinist with the Indianapolis Drop Forge Co. in 1900, the younger Baker earned the almost unbelievably low salary of 88 cents per day. But he still found enough leftover energy — after a 10-hour workday — to take nightly gymnasium workouts at the South Side Turners establishment. The exercising was not of the routine variety — Baker never settled for anything that was only average — but was designed to condition him for acrobatics, and he became an expert in torso-twisting and tumbling.

While on tour with the Turner acrobatic aggregation Baker teamed up with Bill Irrgang, a champion athlete, and they developed an act of their own which ended with Baker punching five bags at once with his fists, feet, and his head. The act was a crowd-pleaser and eventually brought a contract with a vaudeville outfit which paid the pair $100 weekly in 1906 for a three-a-day schedule. But the two Hoosiers discovered the bright lights of the stage had drawbacks too. A few months after getting into the big time they gave up in San Francisco and headed back to Indianapolis.

Indeed, their decision, although made quickly, was a fortunate one. Within hours of their departure for the Midwest the great San Francisco earthquake occurred and destroyed vast sections of the city, including the hotel where they had been staying. Baker returned to his job at the forge firm and went out and bought a new Indian motorcycle. A short time later, he was to make a second big decision which was to change the course of his life.

The Elks lodge held a huge Fourth of July celebration at the Crawfordsville, Indiana, fairgrounds in 1908, and a few riders still were needed to fill out the starting fields in the motorcycle races. Baker, on an impulse, signed one of the entry forms. He surprised himself by winning his first start and placing second in another. The thrill of racing encompassed him and he decided this would be the life for him to follow. It took Baker a full year of intensive practice to master the technique of riding the turns — a real art in those days, for the rules forbade the steel-shoe system now in use. Baker took at least one nasty spill at the Indiana State Fair track before he finally learned to get around without dragging his foot. His sojourn among the amateurs did not last for very long; he was in the professional ranks by 1909, riding on different factory teams for a salary and on an all-winnings basis.

On August 19, 1909, a three-day extravaganza of auto and motorcycle races opened the newly constructed Indianapolis Speedway — two years before the first of the famous 500-mile classic was run. Baker was an entry in the 10-mile national championship event aboard his Indian motorcycle. The track had not yet been paved, and the dust was thick enough to cut, but Baker outclassed a field of star bike-men and the nation's speediest machines to clinch his first crown.

The Indian bikes were built by Hendee Manufacturing Company, Springfield, Massachusetts, and the firm was steadily expanding its racing team which was making Indian a top seller across the nation. Baker became one of the company's best recruits. The founder of the firm, George H. Hendee, was a former bicycle champ, and he liked the robust, raw-boned Baker. In 1912, Hendee gave Baker his first big break — a 14,000-mile goodwill tour of Cuba, Jamaica, and Panama, to spur the motorcycle market there. It was Baker's initial assignment for the Indian manufacturer, and during the 12 ensuing years he never bothered with a written-contract; a handshake with Hendee sufficed.

On this endurance excursion through the Caribbean, Baker encountered horrible road conditions. But as he struggled through the back country roads and paths, he discovered he had an almost unlimited stamina, and could go through days of high speed travel with a minimum of sleep or rest, providing he had plenty of food.

Baker's powers of endurance paid off on May 14, 1914, when he scored a major triumph for the Indian camp by riding a seven-horsepower, twin-cylinder, electrically equipped, two-speed model from San Diego, Calif., to New York City in 11 days, 12 hours and 10 minutes, to clip nine full days off the previous transcontinental record. In newspaper accounts of the victory it was disclosed that Baker had never ridden the stock motorcycle until three hours before the start of his trip. The solo ride took him over four mountain ranges, across 1027 miles of desert, 232 miles of prairie mud, and 64 teeth-rattling miles down a railroad track, which was easier riding than what the surrounding terrain had to offer. Baker cycled from 200 feet below sea level to nearly 10,000 feet of altitude in the mountain passes, and he tallied a total of 3378.9 miles in the jaunt which taught him scores of invaluable pointers that he would use in later distance journeys. He became known as a "trans-continentalist" — a term which he coined and began to use. even on his stationery.

On November 9 of the same year, Erwin Baker returned to the Southwest where he bagged the 537-mile Borderline Derby race on an Indian — speeding from El Paso, Texas, to Phoenix, Arizona, in 15 hours, 52 minutes of continually tough riding. These two feats won the reputation of America's ruggedest motorcycle for the Indian Power-plus, rated at 7 hp though it developed 15 to 18.

A New York City newspaperman called Baker "a cannonball" because of the way he came zipping across the finish line in his races. Baker liked the monicker and adopted it as his nickname, a nickname which became immortal during the next three decades.

Combined with his Three-Flag-Drive — from Canada to Mexico — it was a big year for the Cannonball. His north-south run from Vancouver, B.C., to Tijuana, Mexico, covered a distance of 1835.5 miles, and he pushed his Indian to victory in three days, nine hours, and 15 minutes. But 1916 loomed even bigger as Baker began his Australian tour for Hendee, an assignment which he called "one of my more ruggedjobs."

On a special course at Mortlake, Australia, Baker went after the world's 24hour record. He and his motorcycle were menaced frequently by vast flocks of rabbits dashing in front of them, and frightened coveys of king-sized parakeets buzzed him on countless occasions. But he managed to avoid a serious mishap, and shattered all previous marks of the 200, 300, and 1000-mile distances, even though a torrential rain drenched him and the course during most of the try. He finished the effort with a new world road mark of 1018 3/4 miles. As he came into the homestretch his leather suit had dried to armor-plate stiffness, and his colleagues were obliged to cut it away from him before he could rise and walk away from his machine.

Baker also trail-blazed his way through another feat when he made the first complete circuit of Oahu in the Hawaiian Islands — 90 miles of gritty riding on the island's unimproved and almost primeval shoreline.

In 1917, Baker felt a good, solid plank track beneath the wheels of his Indian as he set an entire list of new records at the Cincinnati Speedway.

Unusual accidents were experienced by the veteran throttle-twister. One night, in a try for the 24-hour track record, he took off his goggles and promptly connected with a big bug which he caught smack in the eye. The impact was so great that Baker and his bike spilled all over the track. But Baker got back on the bike and stayed in the running, ending up with a heretofore unheard-of distance of 1534 3/4 miles. Baker was ditched many times by barking dogs, or other frightened small animals. Once, in Indiana, he smacked into a fence and was tossed onto the back of a surprised cow munching grass on the other side of the wire. Natural road hazards and encounters with storms, however, were the worst problems for Baker, but even these conditions had advantages. Road records made against great handicaps were terrific sales incentives for they showed the durability of his machines. Following Baker's 1914 cross-continent record, colorful full-page ads appeared in newspapers and magazines, showing an Indian chief looking down from a high cliff upon thousands of motorcycles and riders. The copy read: "50,000 Indians are coming in 1914."

Among the more rugged events on the west coast was the San Francisco Motorcycle Club Endurance run on February 22-23, 1919, and Cannonball was one of the seven survivors out of 30 entries. It consisted of two round trips between San Francisco and Santa Cruz totaling 580.4 miles of rain, hail, snow and a landslide as an added hazard. This threw Glen Stokes into a bad spill where he suffered a broken shoulder, and Stokes was one of the best competition riders.

Lewis Grey plunged off a bridge near Pescadero and broke his ankle; but Hap Alzina, on an Excelsior sidecar, pounded out the only perfect score to win this nightmare-on-wheels; Wells Bennett, another Excelsior record holder, had the best solo score tor second; and Cannonball Baker wound up third overall and second in the solo class.

But Baker wanted to get back his transcontinental record, and the Indian company gave him his chance to better the mark of Alan Bedell, on a four-cylinder Henderson, who made the long jump in 7 days, 16 hours, 16 minutes in 1917.

His 39th cross-country record attempt — counting many in autos — started in New York, June 15, 1919, on an Indian Powerplus twin, under M.A.T.A. sanction. After the ferry-boat crossing of the Hudson, he hit the road at Perth Amboy, New Jersey, and was in Philadelphia in 2 hours and 6 minutes. It would have been 2 hours flat, except for the Sunday drivers he had to dodge.

As darkness fell, thunderstorms plagued him as he wound through the winding roads in the Laurel Mountains of Pennsylvania, newly oiled and slick from the downpour, but the indomitable Baker droned on through the night and crossed the Ohio river at Wheeling, West Virginia, an hour and forty minutes ahead of the record.

In 23 hours and 44 minutes after leaving the Atlantic coast he chugged into Terre Haute, Indiana, still ahead of his record. Here he caught some sleep while his personal mechanic worked on the machine.

Rain could make the dirt and gravel roads of that day a challenge, and in Illinois he tried to ride a railroad track to escape the mud and was arrested, which cost him 12 hours time and all chance for a record.

Baker's next sidecar record try occurred in 1921 when he carried a famous Indian race rider, Earl Armstrong, along as a passenger. Since it was believed that Armstrong would be near exhaustion at the halfway point, a relief man was dispatched by train to meet them at Marshall, Missouri. When Baker and Armstrong arrived at the town about 1:30 in the morning they were unable to locate the relief man, named E. Bernier. Although they canvassed the hotels and woke up about half of the residents of Marshall, they could not find a trace of Bernier — until they tried the jail. There they found Bernier sleeping peacefully. Police thought he was some kind of nut when he claimed he was waiting for someone to arrive in Marshall on a motorcycle.

On Sept. 23, 1922, Baker started from Los Angeles for New York City aboard an Ace four-cylinder bike, and zipped along at 75 mph while the good California highways lasted. But then came a spell when he could go only six mph in the sandy deserts to the east. He encountered only a smattering of mud in Arizona and a couple of brief showers in Kansas as he covered mile after mile. Sporting a heavy beard and bloodshot eyes, Baker chugged into Gotham at 12:52 a.m. on Sept. 28. He had filled out the distance from the Pacific to the Atlantic — on a 3332-mile route — in a record six days, 22 hours, and 52 minutes. And during the trip he had only nine and one-half hours of sleep. The original set of U.S. traction tread tires still were on the wheels of his cycle, an accomplishment which had saved him time during the run, but Baker had another explanation concerning the good weather he had encountered. "I could have left my umbrella at home," he said. Nevertheless, the perfect performance of the Ace four-cylinder motor was a factor; Baker had to change only two plugs and adjust valve tappets once in the long period, proving it one of the best bikes of the 1920's.

Cannonball Baker was much more than a throttle-happy daredevil with an aversion to a normal amount of sleep; he was a genius in getting the last ounce of top performance out of almost any kind of motor. He rode, in addition to Indians, Aces, and Ner-A-Cars, automobiles carrying the names of Cadillac, Templar, Franklin, Jewett, Crosley, and others, across the the U.S. and on an array of tracks to attain speed and economy marks.

Following his epoch-making 1922 coastto-coast run from the west, he went on an economy test for Ner-A-Car, making a return trip - from New York to Los Angeles — during which he used but 40 gallons of gasoline and five quarts of oil. His time: 179 hours, 28 minutes, for an even 20 mph average.

Baker returned to his first love, the Indian motorcycle, for one more record in 1941, after posting more auto road marks than anyone else in the field. He was getting a little paunchy in his middle years but he told Indian company officials, "I can stand it if the machine can."

The roads of 1941 were far superior to those of his early ocean-to-ocean drives and there now were balloon tires for a smoother, quieter ride. Engines had improved too, so the old master cut out another fast run across the U.S. in only six days, seven hours.

When Erwin G. Baker died at his Indianapolis home on May 10, 1960, the large part of a flamboyant era died with him. Road tests continued — on through today — but they no longer were so grueling as they were shortly after the turn of the century. Modern research and science had simplified the task considerably.

That is why men talk of the feats of the great Cannonball. Not only had he raced and endured hardships which would make many riders today flinch at the thought; he had pioneered thousands of dangerous miles to show engineers what was good or bad with their designs, so that the builders of motorcycles and motor cars could build them better in the future.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue